At His Rebbi’s Command

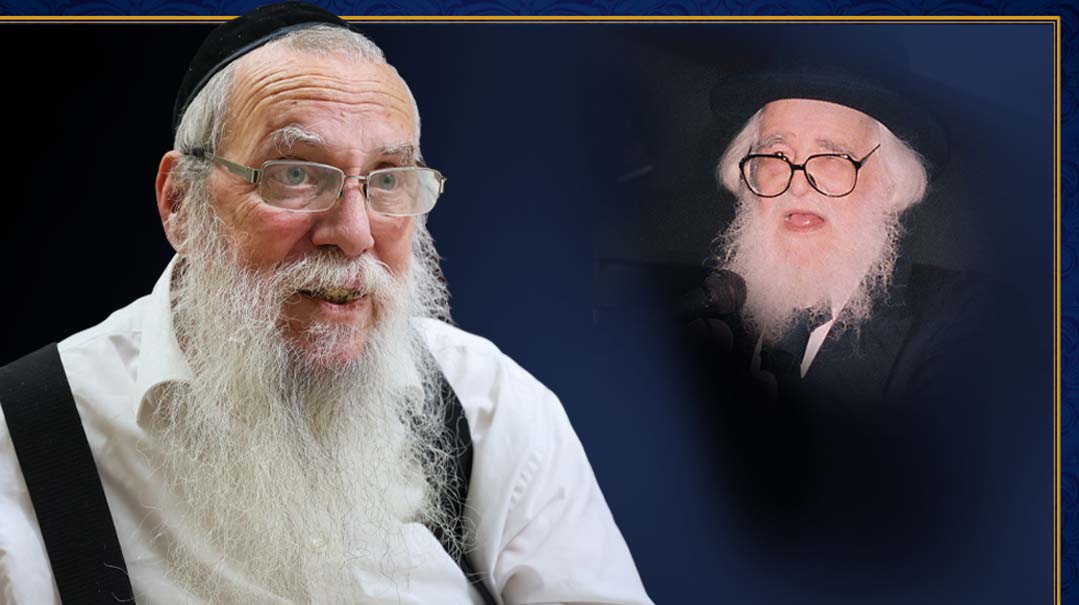

| November 23, 2021Rabbi Refoel Wolf Shares His Privileged View of Rav Shach

Photos Itzik Blenitsky, Personal archives

Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach ztz”l, whose 20th yahrtzeit was recently marked, was an enigma: On the one hand, he wasn’t shy about speaking up and giving daas Torah to a sometimes-resistant public; on the other hand, this venerated rosh yeshivah of Ponevezh was extremely humble and self-effacing, not even understanding why throngs would approach him for brachos. Yet he was the father of the yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael — and not only the ones he founded and encouraged: When he heard that a child hadn’t been accepted in any school, he’d gather a delegation together and personally approach the principal. When he was elderly and had little physical strength (he passed away at 103), he still refused to go to sleep until he finished the number of dapim he committed himself to complete. “I’m an old man,” he’d say, “and I don’t know what will happen to me from day to day. I want to finish the perek in order to arrive in Shamayim with yet another perek of Gemara in my hands.”

Rav Shach was no stranger to controversies that seemed to follow him until the end of his life — as they often do to those unafraid to state politicly-incorrect ideas or sugarcoat daas Torah. Rav Shach was rosh yeshivah of the world-class Ponevezh yeshivah, although he never considered himself anything but a servant of the beis medrash, humbly making sure his days and nights were saturated with Torah learning. In fact, he requested that all pashkevilim written against him should be buried with him in his kever. He often said how all the insults a person gets in This World will help tremendously to lighten his judgment in the Next World. A talmid chacham’s wife once complained to Rav Shach that her husband was suffering from public insults. In response, Rav Shach took out a rope someone once sent him as a subtle threat. Rav Shach requested that it, too, be placed with him in his grave.

Rav Shach’s public involvement often came at another steep personal cost: It exposed him to the spotlight and forced upon him honor and trappings that were intolerable to him. “Whenever the Rosh Yeshivah attended an event, like a bris milah or siddur kiddushin, he immediately went over to the baalei simchah and said, ‘I’m here, there’s no reason to announce my name,’ making sure to prevent them from announcing him with all kinds of honorifics,” says Rabbi Refoel Wolf, right-hand man of the Rosh Yeshivah. For many years, Rabbi Wolf was privy to the gadol’s inner sanctum, having witnessed from there many personal moments as well as significant developments that affected the larger Torah community in Eretz Yisrael. He has an endless wellspring of details, on the scene when fates were rendered with clear daas Torah.

Their connection was originally based on family acquaintance from the early days of Ponevezh, when Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman ztz”l, the Ponevezher Rav, would regularly stay at the home of the Wolf family when he came to London to fundraise for the yeshivah. Rabbi Wolf was just a little boy then, but the Rav’s obvious love of Torah and his yeshivah captivated young Refoel, and when the time came, it naturally followed that he would attend the yeshivah as well.

“The personal connection between Rav Shach and me began after a difficult surgery that he went through,” Rabbi Wolf recalls. “The Rosh Yeshivah, who was already elderly then, was still very independent — he hardly ever asked for anything. Even at the end of his life, he never let anyone help him put on his shoes, not even his grandchildren. He was the one who opened the door when someone knocked, insisted on preparing his own tea, and when he needed a sefer, he’d get up, slowly go to the bookcase and take it himself. Bochurim in the yeshivah already got used to not asking the Rosh Yeshivah if they could help him. He would say, ‘Einer alein — I am a person alone.’ But after the surgery he needed someone next to him.

“Rav Yechezkel Eschayek would often drive him from place to place, borrowing his father’s car. At the time, Eschayek and I shared a room in the dorm, and he suggested that I be with the Rosh Yeshivah in the hospital. Of course, I grabbed the chance, and later, when Rav Shach went to the convalescent home of the Vaad Hayeshivos in Netanya, I followed him. When Rav Shach asked what I was doing there, I told him that the doctors had ordered me to rest, and he said, ‘Then come and share my room.’

“About a week later he returned to yeshivah, but he didn’t forget me. The next time I passed him, he stopped me and asked, ‘How can I thank you?’ I replied that I wanted a close connection with the Rosh Yeshivah…

“‘Nu, aderaba, come in to me whenever you want,’ the Rosh Yeshivah replied. And I did.”

Oops! We could not locate your form.