Another Window Closes

Remembering Rabbi Menashe Tzvi Winkler

Last winter, when Yehuda Geberer and I were planning our “Eyes That Saw Angels” piece for the Pesach magazine, I felt something was lacking. We had lined up interviews with people who vividly recalled encounters with Rav Meir Shapiro, the Imrei Emes, Sarah Schenirer, the Minchas Elazar, and even Rav Kook. But the olam hayeshivos needed representation, and the options were seemingly few and far between.

One day I had an epiphany. I dialed my close friend, the esteemed longtime director of development of Mir Yerushalayim, Reb Mordechai Grunwald. Perhaps he’d know of an “alter Mirrer” who could regale us with tales from the world of old and help broaden the connection for the tens of thousands around the world who follow the Mir mesorah.

“Dovi, I have just the person for you,” Reb Mordechai said excitedly into the phone.

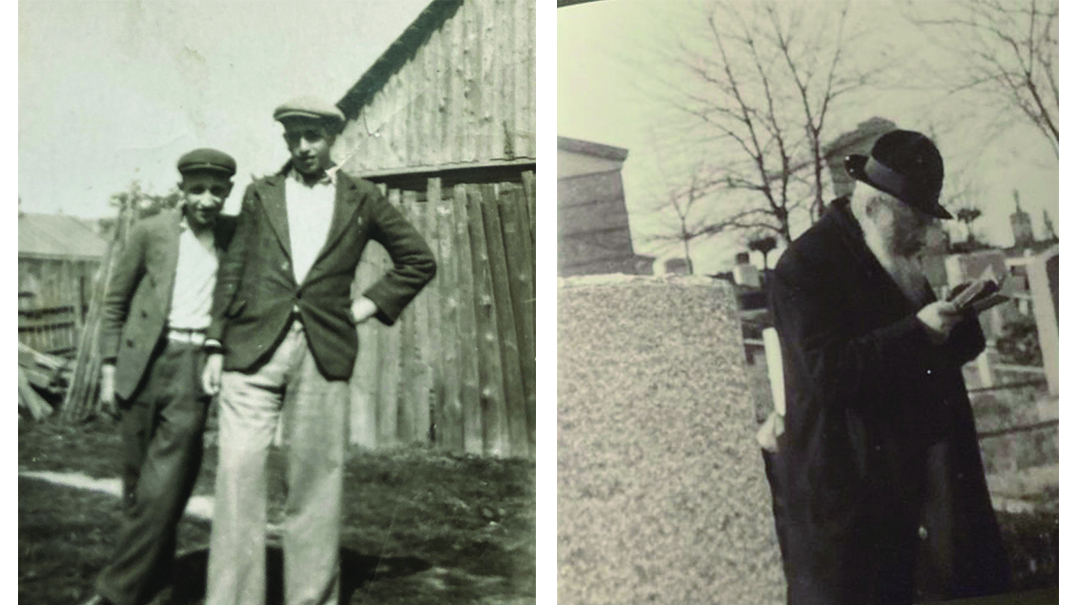

When he told me that Reb Menashe Tzvi Winkler (long past the century mark) was still with us and living with his daughter in Lakewood, I almost danced with excitement. I knew of his story from the famous photo I’d seen of Rav Elchonon Wasserman davening at the Queens kever of his father, Rav Michoel Shalom Winkler, who had passed away suddenly while fundraising in America in 1932.

I was not aware that in addition to learning in Baranovich, Reb Menashe was also a talmid of Radin, Kamenitz, and Mir who had survived the war in the most miraculous fashion in his native Denmark. In 1955, Reb Menashe moved with his family to America, where he lived in Brooklyn until moving to Lakewood some three decades ago. With the kind assistance of his grandson, Ari Griver, I was able to visit Reb Menashe in February, an experience I’ll cherish for life. With his passing last week, I felt it was important to rehash just one decade in the storied life of this incredible man.

Rav Michoel Shalom Winkler was appointed rav in 1914 by the Machzikei Hadas community in Copenhagen, Denmark. Following his tragic 1932 passing, it was clear that his young son Menashe would have to travel to the great yeshivos of Eastern Europe in order to take the next step in his spiritual development.

Located more than 800 miles southeast of Copenhagen, Radin was accessible only by a combined journey on ship, train, and wagon. For young Menashe, coming from modern, liberal Copenhagen, the Radin that he arrived to prior to Elul of 1933 may as well have been a different planet. He was disappointed to discover that the Chofetz Chaim was ill and resting in a forest resort out of town, where the aroma of the pine trees was said to provide health benefits. Fourteen-year-old Menashe Tzvi rushed there to meet him and was awed by the saintly appearance of the nearly century-old “Kohein Gadol” of Klal Yisrael.

“What can I say, it was akin to gazing at a malach,” he recalled.

The young bochur approached the Chofetz Chaim, who asked him where he came from. When he replied that he came from the Radin yeshivah (where he was to begin his studies), the Chofetz Chaim expressed happiness and proceeded to bless him that he should shteig in yeshivah with simchah, serve Hashem in good health, and merit arichus yamim.

“The last brachah seems to have been borne out to fruition,” Reb Menashe quipped nearly 90 years later. That was to be his only time meeting the Chofetz Chaim — who was niftar a few weeks later on 24 Elul.

Menashe Winkler would spend the next six years progressing through Europe’s top yeshivos. After three zemanim in Radin, he transferred to Baranovich, where he developed a close relationship with Rav Elchonon Wasserman.

“As opposed to other roshei yeshivah, who would say a weekly shiur, Rav Elchonon would deliver shiur on a daily basis,” he said, adding with a hint of pride, “and I was able to follow.”

He later recalled other young scholars at the yeshivah. “I remember Nachum Troker [Partzovitz] arriving. He was a young boy wearing short pants. He was younger than me by several years, but we all had great respect for him. Another one of my friends there was Shmuel Kishiner [Berenbaum], one of the yeshivah’s masmidim.”

While a student in Baranovich, Menashe grew ill. Worried about the young Danish orphan, Rav Elchonon visited him regularly and soon decided that the local “doctor” in Baranovich was ill-equipped to handle the issue. “He even sent for [his brother in-law] Rav Chaim Ozer’s personal doctor to come from Vilna to care for me.”

Soon Menashe's mother arrived from Copenhagen and helped nurse him back to health. Everyone in Baranovich was impressed with the “tzadeikes from Denmark.” She was even mentioned as a potential shidduch for the widowed Rav Elchonon.

Menashe Tzvi’s next stop was in Kamenitz, where he heard shiurim from Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz and his sons-in-law, Rav Reuven Grozovsky and Rav Moshe Bernstein. In 1937, he joined his mother and brother as representatives of the Danish community at the third Knessiah Gedolah; they were hosted by their relatives, the Leitner family, in Marienbad. After the Knessiah, Menashe moved on to the Mir Yeshivah, where he would be reunited with Rav Shmuel Berenbaum, and have a chavrusa with Rav Leib Bakst, who served as a father-like figure.

Reb Menashe began to grow emotional as he recounted this to us.

“Why was Rav Leib ‘mekarev’ me?” he asked rhetorically. “Perhaps because I was an auslander and he felt it was his duty to lift me up.”

Reb Menashe would maintain a lifelong relationship with Rav Leib Bakst and other alter Mirrers.

Reb Menashe returned to Denmark prior to Pesach of 1939 as the winds of war swirled across Europe. In April 1940, the Nazis occupied Denmark after two hours of fighting. For nearly three years, Denmark held steadfast against Nazi demands that it deport its Jewish residents. By Rosh Hashanah of 1943, word reached the community that deportation was to begin.

In one of the great rescue operations in history, more than 7,000 Jews were evacuated across the Oresund Strait in fishing boats to neutral Sweden. Menashe Tzvi Winkler, accompanied by his mother and new wife, Esther Rivka, was among those who experienced this personal “Krias Yam Suf,” capping off a whirlwind decade.

The departure of Rav Menashe Winkler from This World is yet another wake-up call, a reminder to stop postponing the simple and urgent act of sitting down with the person who wraps tefillin over a tattoo and listening to his story.

Because he — along with all the older people who regale you with stories of their interactions with gedolim and yeshivos of that “vanished world” — is now an endangered species.

Chap arayn!

I have no doubt that the next generation will wonder how we, who lived in a world populated by these precious individuals, did not spend more time basking in their presence and recording their memories. True, Yad Vashem, the Spielberg Foundation, Project Witness, and other entities have done an incredible job of preserving the memories and experiences of Holocaust survivors. But what about those who can bring us into the bygone world of yeshivos and giants, serving as a vital bridge in our chain of transmission?

As they fade away, it is incumbent on us to record, document, and share their testimonies — so that future generations can be educated and inspired by them.

Is it too late to accomplish this in a comprehensive way? Probably. But that’s not an excuse to shirk from the task. Next time you go visit Bubby and Zeidy, bring along a recorder and ask away.

You’ll thank yourself — and your grandchildren most certainly will, too.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 871)

Oops! We could not locate your form.