Angel of Salvation and Solace

M

otzaei Shabbos in Tosh. The decor is unremarkable — faded linoleum, painted cinder block walls, memorial plaques spread around like autumn leaves.

The gruff sweetness of gabbaim, the animated hum of the bochurim standing guard in various anterooms, the persistent buzzing of a lightbulb, the hope that runs through these rooms like a river.

It’s the smells that capture you.

Perspiration. Hundreds of chassidim who’ve just experienced an intense Shabbos line the waiting room, collective tension and body heat making it very warm despite softly falling snow outside.

The lingering smell of overcooked kugel, challah crumbs, and burning wax. Tosh is a place of candles, which the Rebbe tends with the care of a gardener, seeing stories in each flickering light.

The mustiness of old seforim, Tehillims opened across wooden tables.

Then, after a wait that takes you into a dimension beyond time, long after you’ve despaired on a night’s sleep, the door opens and you are in his room.

And the scent is that of Gan Eden.

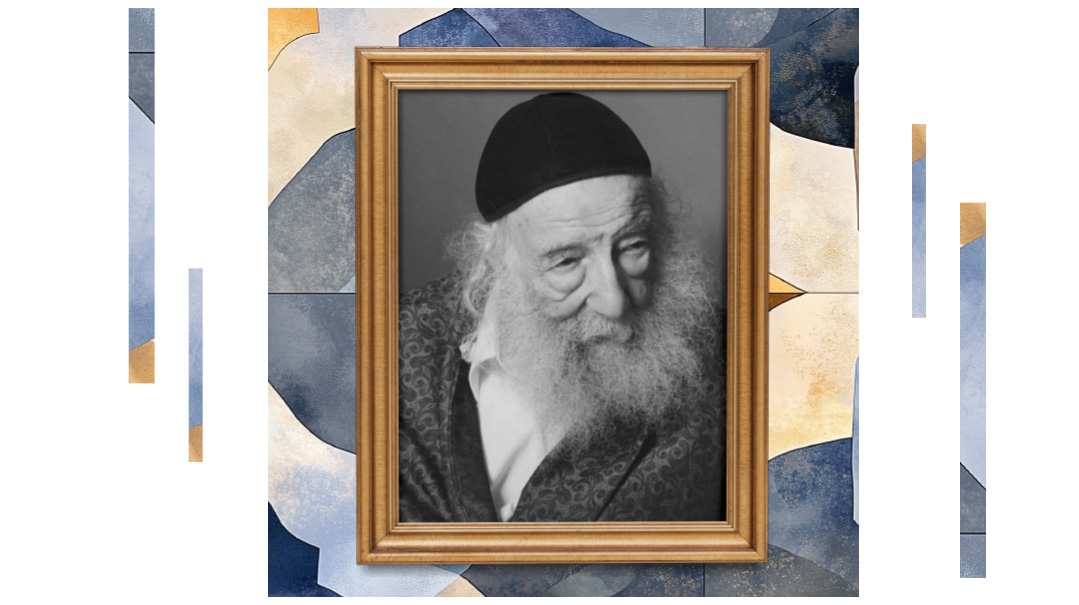

The tzaddik of Tosh raises his pure eyes without moving his head. His smile is that of your grandfather, your great-grandfather, all the sainted Jews who’ve ever loved you. You feel unworthy and elevated at once, undeserving of the love you know is your birthright.

You start to talk, words rolling off your tongue and your heart, more than you planned to say. The Rebbe mumbles too, half-words, nodding along as if he already knows. Then he looks at you, the radiance of his smile an assurance of its own.

Not only that all will be well, but that all is as it’s supposed to be, that the Eibeshter will help.

The Tosher Rebbe didn’t just make things right; he also made sure that the lines of people who came into his room with sagging shoulders and furrowed brows left knowing that there is a Creator in the world.

We No Longer Cared

Rav Meshulam Feish HaLevi Lowy arrived in Canada with little. Though respected for his lineage and learning, few believed that there was a future for the old-world model of a Hungarian rebbe. A court sustained by miracles that spawned more miracles could work in the Hungarian countryside; there, this one would bring fresh eggs, another potatoes in exchange for the tzaddik’s blessings.

This was a new world, life moving faster than the wagons of little Nyirtass.

There were stories, however, that came along with this rebbe — things that made people pause. In the Hungarian Labor Service, in which he’d survived the war years, there had been a Jew charged with the unpleasant task of cleaning the latrines during the predawn hours. He complained about the revolting job he’d been given; when he arose during the night to follow orders as everyone else slept, he found that it had already been done. The next morning and the morning after that as well.

Eventually he forgot about the job, assuming it would be done, never learning the identity of his anonymous collaborator until the Tosher Rebbe left the camp.

About five years ago, the Tosher Rebbe was in a hospital and one of the other patients heard that the famed Rebbe was there. He pleaded with the gabbaim to allow him a glimpse of the Rebbe’s face. They wondered why he — who clearly had no affiliation with chassidus — cared so deeply, and he told them about those first few months after the war.

“Most of us planned to build new lives with no Yiddishkeit. It didn’t speak to us anymore, after what we’d endured. But then…” The patient looked into the Rebbe’s hospital room and his voice quivered. “…then we heard this Yid say the words, ‘Kadosh, kadosh, kadosh,’ and we knew that there was a Ribbono shel Olam in this world. We owe him everything.”

A group of Hungarian Yidden helped the Rebbe purchase a small home on Montreal’s Jeanne Mance Street and Tosh chassidus had a home. From the outset, it was less about rebuilding the dynasty and more about breathing life into Yidden.

The small children of the Lowy family rarely greeted the new day in the same bed in which they’d gone to sleep; the house belonged to the people, a welcome center for immigrants. Rebbetzin Chava was cook, maid, and counselor, serving up food and reassurance in the same spirit of generosity with which her husband offered words of Torah and hope.

A Montreal old-timer shares a story dating back to those early days, when the tzaddik of Tosh presided over a shul with just a handful of members:

One Sunday morning, a Hungarian survivor came to receive the Rebbe’s brachah. He was moving to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he had a business opportunity and hoped to start life anew. The Rebbe encouraged him to remain in Montreal, with its vibrant kehillah, rather than spiritually barren Halifax.

The visitor told the Rebbe of his difficult history. He’d lost everybody and everything in the war, and, realizing that his destiny was in his own hands, he threw himself into work, accepting any job he could get, until he’d saved up $500 in American currency — seeds of a new life. On his way out of Europe, at the train station in Antwerp, someone jostled him and his suitcase — his only possession in the world, carrying all his wealth — was stolen.

The cruelty of the act seemed akin to murder, for the thief had taken his dreams, his will to live, his only hope.

Nevertheless, he resolved to go on, getting back to work and saving a modest amount of money. Once again he started his journey, but this time, he would see it through until its end. A distant relative in Halifax offered him a respectable job and this Jew made arrangements to settle there. He was through with running, he told the Rebbe, and asked for a blessing.

The Rebbe saw his determination and offered him a warm blessing. The Jew left.

That afternoon, as this visitor davened Minchah, he noticed an unfamiliar fellow staring at him. “Do I know you?” he asked.

“I’m not sure,” the second man suggested. “But you look so familiar. Tell me where you’re from.”

They began to speak, listing the various places they’d both been.

Suddenly, the second man’s face paled. “Wait, were you in the train station one day... and did someone snatch your suitcase?”

“Yes!” the man’s eyes shot open. “How do you know?”

The fellow looked down. “It was me. Forgive me. I was crazed by mourning, near-starving, and I didn’t think. I never forgot your face. Please wait here for a minute.”

He left the shul and returned a short while later with a packet of money. “Here is everything I have, $1,500. Please take it all, the $500 I owe you and the rest as an apology, to show you the purity of my intentions.”

With that, he turned and left the shul.

The first man accepted the money with enthusiasm, seeing it as a sign that he should remain in Montreal and build a life there using the newfound money. Although he succeeded in establishing himself in Montreal, his relationship with the one-time thief remained strained. Several years later, he made the decision to relocate to New York. The night before he was to leave, the second fellow approached him.

“I have to tell you the truth,” he confessed. “You owe your nachas, the beautiful family you built, to the Tosher Rebbe. He persuaded me to claim responsibility for the theft, even though I was never in Antwerp in my life and I’d never seen you before.”

The chassid who tells me the story pauses. “Now, we know how much the Rebbe paid the first person — $1,500. But we’ll never know how much it cost him to persuade the second man to claim responsibility.”

I Have to Do Mine

In the early 1960s, about ten years after his arrival, the Rebbe set out to realize a vision: he and a small band of devoted souls found a suitable plot of land north of the city upon which they would build their shtetl.

According to legend, when the Rebbe and two confidants made the trip out to make an offer on the property, none of the three even had the requisite dime for the highway tollbooth.

But Tosh wasn’t built with money.

The hamlet came into existence with 18 families; from the day that it was established, never again would a Jew say “I have no home.”

And like the village itself, the Rebbe established a yeshivah where every bochur was welcome.

The learners and dreamers, the workers and slackers, they all found a place on the worn benches of Tosh; it was an island where the most sophisticated oveid Hashem could find fulfillment and the struggling soul could find hope.

For some, the icy winds that swept through Rue Beth-Halevy erased the past, offering a second chance; for others, it blew out the distractions of this world so that they could continue to serve Hashem in complete purity. To all, the tzaddik with the eyes of a child was the center of the universe, a defender and a father.

He was a small man, a body kept together by fragments; he ate little, slept even less. Yet just as he defied reality when he easily lifted his huge jug of water for netilas yadayim, he carried them all, his thin shoulders big enough for their worries, fears, and troubles.

The Rebbe didn’t belong to Tosh. Jews from all over found their way to the Canadian hamlet.

One of the great riddles of Tosh is how a chassidus that drew magnates and tycoons from all over was always underfunded, its mosdos teetering on the edge of insolvency.

The answer has its roots in a decades-long, good-humored battle that played itself out between the Rebbe and his gabbaim. Money piled up on the table, expressions of hope and appreciation; fast as it came, did it go.

Nothing, it seemed to the frustrated local askanim, remained for the local mosdos.

The Rebbe wasn’t building up Tosh, he was building up people everywhere else.

One Motzaei Shabbos, a steady supporter who felt especially grateful to the Rebbe made a generous donation.

Later that night, a visiting Yerushalmi meshulach asked the supporter for a ride back to Montreal. The supporter was happy to accommodate him, and as they drove down Highway 15, the driver was surprised to see his passenger holding a familiar green envelope. It was from his business, with his logo on the corner.

How did the fellow sitting next to him get an envelope from his business?

The Yerushalmi brightly explained how he’d come in to the Rebbe and shared his many problems. The Rebbe had reached for the still-sealed envelope on his table and handed it to the visitor.

The collector turned to his driver. “Do you know how much money was in there?”

The driver was quiet. He knew exactly how much was in there! Ten thousand dollars — ten thousand dollars that he had accumulated with great toil and effort. He’d saved that money, imagining the Rebbe’s joy when he looked inside the envelope — but the Rebbe had never even opened it.

Later that night, he turned around and headed back to Tosh, back to the Rebbe’s room for the second time. The Rebbe understood the unexpressed question and he spoke softly.

“Di darfst tin deintz, you have to do yours. I have to do mine,” he said.

Late one night, two young men from Montreal came in collecting money for a cause; the Rebbe listened and appeared anxious to help. “They already took everything away,” he indicated to the empty table. He flung open the drawers with urgency, pulling out envelopes that had arrived in the mail and opening them, looking for money.

From here a twenty, from there a fifty... his desperation to help willing a little mountain of money into existence. His joy was palpable as he pushed it toward them. “Here,” he said, beaming, “take it.”

Another time, a visiting meshulach shared a tale of woe with the Rebbe. “What a zechus it would be to help you,” the Rebbe exclaimed, and asked the gabbai to get some money. The moment the gabbai stepped out, the Rebbe slipped off his shoe and removed an envelope stuffed with cash.

“Take it,” he urged, handing it to the dumbstruck collector, “put this in your pocket.”

A moment later, the gabbai returned with a $10 bill, which the Rebbe handed his visitor with a smile — and a twinkle in his eye.

Out of Jail

To be a Tosher chassid meant to understand what money is for, and to be ready to part with it for “an important mitzvah” at any time.

The Rebbe once called an American chassid and asked for $40,000 immediately.

“I don’t have it,” the chassid replied.

“Sha, sha,” the Rebbe said gently, “der Eibeshter hert, be careful with your words.”

The chassid quickly reconsidered and sent over the money.

All the Rebbe’s emunah notwithstanding, there was a time of particular financial strain in Tosh, when it looked like the bank would foreclose on one of the buildings. The askanim informed the Rebbe that they needed a significant amount of money by the following Wednesday.

On Sunday, a Jew came in to the Rebbe with an alarming tale about problems with the Mafia. He needed to repay his debts by the next day or suffer Mafia justice; the Rebbe handed him a huge amount of money.

Sympathetic as they were, the askanim who’d been working around the clock to save the mosdos were disturbed that the Rebbe had given away all the money. The Rebbe was incredulous. “I don’t understand. He needs the money on Monday, and we don’t need it until Wednesday. In two days, the Ribbono shel Olam can do anything!”

Many of the Rebbe’s miracles involved those who’d stumbled and encountered legal issues. He once solicited a wealthy donor on behalf of a Jew who’d been convicted of a severe offense.

“But Rebbe, he’s a criminal,” the donor protested.

“For whom do you think Chazal instituted the halachos of pidyon shevuyim?” the Rebbe shot back. “And besides, there are so many sippurei tzaddikim about how all the rebbes used to engage in pidyon shevuyim — but those maiseh bichelach don’t tell you why these Yidden were sitting in jail.”

Th courts would give their rulings and physicians their diagnoses, but Tosh was a place of mofsim; the Rebbe’s utterances and mumbled assurances proving stronger that CT scans and verdicts.

An Israeli citizen needed to enter the United States, but he had no passport. The Rebbe asked for a map of the US-Canada border and looked at the various points of entry. “This one,” he said, indicating a particular crossing, “and you’ll be fine.”

A young man was facing a stiff jail sentence and his lawyer was able to negotiate a plea bargain of five years’ jail time. The attorney felt that it was a good deal, and he urged the defendant to accept it. The askan working with the lawyer accompanied him to the Rebbe for approval. He explained that the sentence could be as high as 25 years, and the lawyer felt that they should accept the smaller sentence.

The Rebbe began to laugh.

“Why is the rabbi laughing?” the lawyer inquired.

“Veil in Himmel zugt men ehr zohl gurnisht zitzen, because in Heaven they say that he shouldn’t sit at all,” the Rebbe said.

The askan repeated the Rebbe’s remark to the lawyer, who became agitated. “I don’t know about Heaven, but I do know that in the court system this is the best option. If you don’t accept it, I’m off the case.”

The defendant went to court alone, where the judge lectured him about the severity of his offense. Then the judge, who had appeared so angry, gave a strange laugh and sentenced him — to one year’s house arrest.

To parents of a young man accused of financial wrongdoing, the Rebbe promised that he wouldn’t serve jail time. The court date arrived and he was found guilty. Then, on appeal, the same verdict was reached. It seemed obvious that he would, in fact, sit in jail.

The young man’s brother came in to the Rebbe and reminded him of his promise. “He won’t sit,” the Rebbe assured him again.

“But he was found guilty!” the petitioner said.

The Rebbe reached out and touched the ever-present Tehillim. “This is stronger than they are,” he said.

Inexplicably, the defendant was never picked up to do time. Days passed, then weeks, then months. And then years. After five years, he applied for a new passport and it was issued; case closed.

But perhaps the biggest miracle of all was how ready this man was to give himself away for another Yid — and how he created a community of people like him.

Shacharis at Sunset

The Rebbe had a global vision, aware of events all across the world. On Yom Kippur Night 1973, he suddenly turned around to the chassidim and said, “The Yidden in Eretz Yisrael are in danger. We must daven extra hard for them.”

Yet even as he saw from one end of the world to the next, he didn’t miss the individuals around him.

Late one Shabbos night, the chassidim passed by the Rebbe after the tish, hands outstretched to receive shirayim. A young boy, not yet bar mitzvah, looked on in disappointment as the large bowl of fruit was emptied before he reached the Rebbe.

As the boy was walking out, he heard the thunderous footsteps of a group of bochurim behind him. “The Rebbe sent this for you,” they said, and handed him a heap of nuts.

In Tosh, Purim was a climax of the year. In the court of the Rebbe’s grandfather, the Saraf of Tosh, it was known that the Purim seudah was the most opportune to time to ask for a yeshuah, and the Rebbe too would make lavish assurances for personal salvations during those exalted moments.

Several years ago, Purim fell out on Erev Shabbos. It was a short day, the Rebbe’s holy avodah occupying every moment of those lofty hours. At the peak of the seudah, the Rebbe — his face suffused with the joy and Divine energy of the moment — looked for one of his close chassidim, who sat there, inebriated.

“Come here,” the Rebbe called him close. “Did you forget it’s Erev Shabbos?” the Rebbe whispered.

The Rebbe saw past the hundreds of chassidim, the flow of brachos and simchah, heard past the pounding music and shouted requests. It was Erev Shabbos, the time when this chassid always brought an envelope to a local woman whose husband was incarcerated. The Rebbe handed his drunk chassid the envelope of money and dispatched him on his weekly mission. “It’s Erev Shabbos, and she’s waiting for her money. Hurry over there.”

During the week, the Rebbe wouldn’t begin davening until late in the day, after a long preparation involving the recitation of the entire Tehillim and an intense avodah with his candles. He wouldn’t eat anything until he’d completed davening, which meant that he rarely ate.

One afternoon, as he was about to start Shacharis, a Tosh resident entered; he had a difficult marriage and his wife had announced that she was leaving. Suitcase in hand, she’d walked out. The distraught husband immediately hurried to the Rebbe.

The Rebbe asked his driver to bring his car up to the door of his home. The Rebbe sprung in and then lay down in the back seat, so that he wouldn’t be seen by passersby. He instructed the driver to keep going until they found the woman.

They caught up with her and the driver asked the woman to come into the car. She refused. “The Rebbe is here,” he said.

The woman climbed in to the back while the Rebbe moved to the front.

They drove back to the Rebbe’s room, where the Rebbe sat with her and urged her to return home, advising, pleading, and blessing. Then, with the sky starting to grow dark, the Rebbe returned to his preparations for Shacharis.

Shabbos We Don’t Cry

The Rebbe was ill for the last few years, but to his devoted chassidim, nothing had changed. They still saw the neshamah — the essence of their Rebbe — governing the frail body, still heard his beautiful Torah even though he spoke little.

His smallest gestures were still laden with meaning as before. When his non-Jewish therapist was diagnosed with a terminal illness, he cried to the Rebbe, his patient. The Rebbe waved exaggeratedly, brushing it away, and the therapist recovered. The chassidim saw how the Rebbe’s posture, his sighs and smiles as he read a kvittel, carried import in all worlds. The Rebbe’s saintly countenance still illuminated the head of a tish and the dais at a wedding, and reflected the fire’s glow at the Lag B’omer hadlakah.

In the Rebbe’s dancing, they felt salvation. In his smile, they found solace.

And now all that has moved up to the Olam Ha’emes.

The Rebbe had two sons, Reb Mordche and yblcht”a the newly appointed rebbe, Reb Elimelech.

Several years ago, Reb Mordche collapsed and suddenly passed away on an Erev Shabbos. When the Rebbe heard, he asked for some time alone.

He spent several minutes confined to his room. And then he made a phone call. He’d been working to make shalom bayis between a couple, but the husband had been unmoved by the Rebbe’s pleas. Now, the Rebbe called him and asked him to try to make it work. The husband had already heard what the Rebbe endured, and the holy words offered during those shocking moments of grief softened his heart.

Later that terrible day, as the Rebbe prepared to go to shul for Minchah, he stopped off at his grieving daughter-in-law’s home. He spent a few minutes speaking with her, encouraging her, and then said, “Shabbos... Shabbos m’veint nisht, we don’t cry.”

And he came into shul, radiant as on every Erev Shabbos.

Last Shabbos, parshas Re’eh, was a special time in Tosh. The new rebbe presided over a Shabbos filled with hope and the comfort of shared yearning. Shabbos, the heilege Rebbe taught, we don’t cry.

But then Shabbos came to a close.

An older gentleman I spoke with, a man of poise and dignity, explained to me that survivors don’t cry. Not in this world, the new one. They left the tears behind.

Then his voice broke. The tears came.

Because the Tosher Rebbe didn’t belong to this world, but to that one.

The Tosher Rebbe, man of miracles, was proof; in a world of cynicism and mockery, his life was a testimony that there was a time when such people existed. That through toil, selflessness, purity, and total attachment to the Creator, one can rise above nature in a million ways. That words of Tehillim can penetrate borders, open locked doors, and obliterate dangerous illness. That a smile can nourish and heal. That a man can be an angel, yet still guide like a father and comfort like a mother.

For the Tosher Rebbe, we’re allowed to cry.

Realizing The Dream

R

av Meshulam Feish HaLevi Lowy was born in 1922 in Nyirtass, Hungary. His father, Rav Mordechai of Demetsher, was the son of Rav Elimelech of Tosh. After surviving World War II in a labor camp, Rav Meshulam Feish was appointed Tosher Rebbe. In 1951, he and his wife, Rebbetzin Chava, moved to Canada, settling in Montreal.

In 1963, he realized a dream of establishing a chassidic village about half an hour north of Montreal, in Boisbriand, Quebec. The village attracted families who wished to pursue a life devoted to spiritual pursuits, and despite many bureaucratic hardships over the years, Tosh flourished.

Today, the village has over 400 chassidic families, all centered around the Rebbe and his beis medrash. The Rebbe was revered across the Jewish world, known as a pillar of prayer and brachah and renowned for his advice — particularly in areas of business, law, and medicine.

His talks during Seudah Shlishis revealed a mastery of Torah, and many of his derashos and insights are included in his seforim, Avodas Avodah.

The Rebbe is succeeded by his only surviving son, Rav Elimelech.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 573)

Oops! We could not locate your form.