An Explosion of Gratitude

| November 30, 2021“Shema Yisrael,” I started, accepting the inevitable as my strength gave way

As told by Yanky “Ziggy” Zagelbaum to Rochel Samet

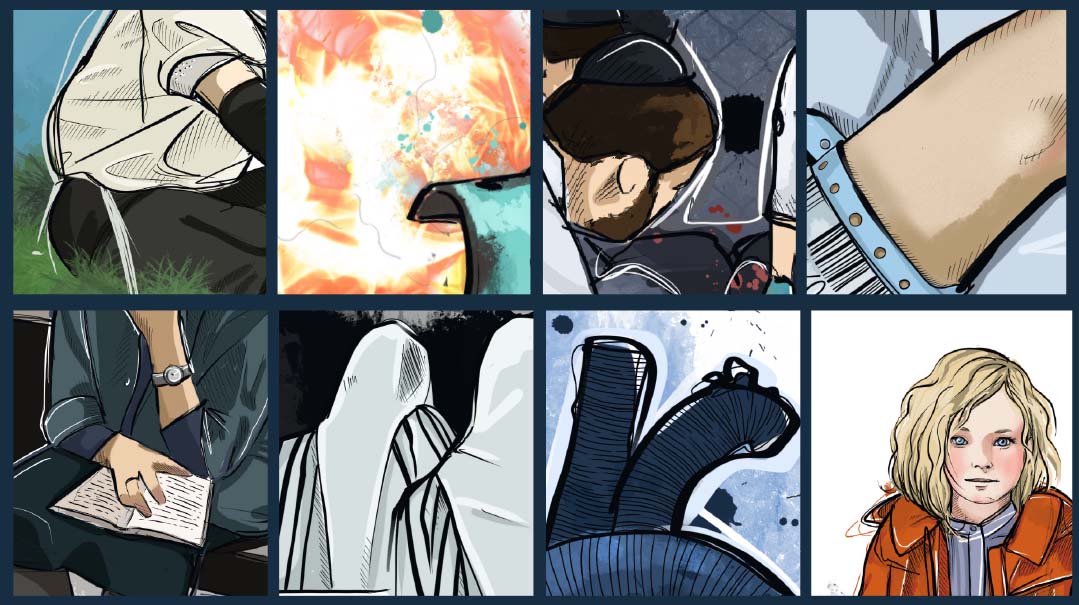

"The building collapsed into tremendous heaps of rubble. Instinctively, I put my hand up to block it, but I was literally under it.”

This July will be 35 years since the explosion that gutted my business and nearly took my life.

It was a routine transaction for the plumbing supplies store I co-owned with my business partner on 18th Avenue in the heart of Boro Park: the weekly delivery of a tank of propane gas. And yet one Tuesday morning, July 21, 1987 — 24 Tammuz 5747 — it turned into anything but routine when, as the workers were lowering the tank into the basement of the store, it happened.

Somehow, some way — to this day, we don’t know exactly — the tank broke open and fell down the stairs. Back in those days, propane tanks weren’t fitted with the safety features they have today, and if the tank opened, gas spewed out like air from a balloon. When the tank opened, the gas filled the basement. That shouldn’t have been a problem — except that we had a water tank down there.

Now this water tank was, for the most part, inactive, used for just a sink or two that provided the store with hot water. It wasn’t even a lot of hot water — there were no tubs, showers, or bathrooms, just a couple of faucets — but when the gas reached the tank’s pilot light, the whole building turned into a huge missile, a tremendous bomb ready to explode.

I was standing in front of the building at 5005 18th Avenue, and I witnessed the entire incident: the workers lugging the tank, the fall, the gas spewing out in a thick white cloud as it was released into the basement. Hardly anyone saw it happen, and those of us there didn’t think anything of it — the tank would empty, the gas would dissipate, and that would be it.

But then — and it didn’t take more than maybe 30 seconds — the cement between the bricks of the building began spraying out violently. It felt like a sudden, powerful sandstorm. And next, the bricks themselves began shooting out like missiles, flying maybe 200 or 300 feet in all directions. It happened so fast there was no time to process a coherent thought; a bizarre horror scene, bricks and mortar erupting from a calm façade as a solid building exploded.

In seconds, I saw the entire building, showcase window and all, rise in the air before crashing back down — onto me, around me, everywhere. The building — and four adjoining buildings — collapsed into tremendous heaps of rubble. Instinctively, I put my hand up to block it, but I was literally under it.

Buried beneath several tons of concrete, bricks, wood, and debris, it was impossible to move. And the dust, oh, the dust. It was so thick, and everywhere, and I literally couldn’t breathe.

Heart racing, racing, racing, a million beats per second, I anxiously struggled for air as I pushed with all my strength at the rubble on top of me. It didn’t budge — and I knew, deep down, I was slowly suffocating.

It’s over, I mamesh can’t breathe.

“Shema Yisrael,” I started, accepting the inevitable as my strength gave way.

Suddenly — I don’t really know how to explain this — I saw my grandfather, who had just been niftar. Zeidy moved one of the blocks near my face out of the way, and I looked up to find a newly formed pocket of air next to the car I’d been blown against and buried beside.

Ah.

I inhaled once, twice — I was finally able to breathe! And once I could breathe, I could scream.

“HELP! HELP! HELP!” I yelled and yelled repeatedly, hoping someone — anyone — would hear me. I have an extremely loud voice; now that I could breathe, I was hopeful.

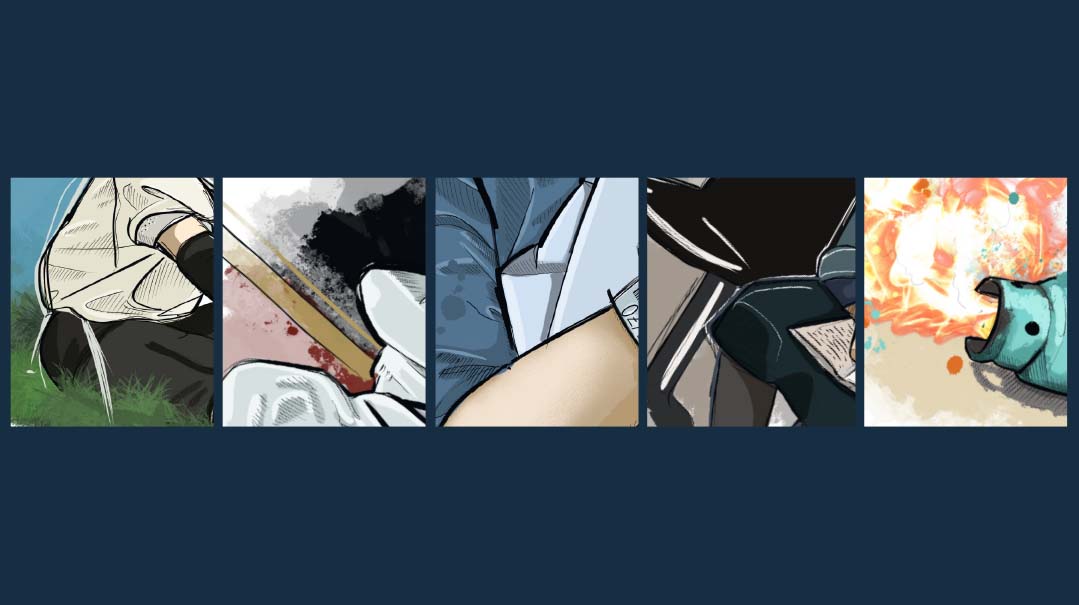

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, I was badly injured — my jugular vein, the one in my throat, had been cut by falling glass, and I was losing a dangerous amount of blood.

“Help!” I cried out again. “Help! Help!”

I managed to extricate a piece of wood that was lodged near my arm and used it to shift some of the rubble in an attempt to attract the attention of someone on the outside.

“Help!”

I was in there for about half an hour when I heard footsteps, and soon, I could see people pulling stuff out of the way. Passersby, alerted to my location by the screaming and movement of the wood, used their bare hands to dig me out.

There were many, many people there — in fact, every year at the seudas hoda’ah, another person comes up to me and claims that he was the one who pulled me out of the rubble. And maybe they all were — there must have been hundreds of people working on the piles of debris, trying to rescue survivors. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one — several other people were also trapped in the mounds of brick and stone.

The tremendously powerful explosion was so loud, it was heard at least ten avenue blocks away, and the houses nearby all shook from it. Crowds of people swarmed the area to help even before Hatzolah and emergency services arrived.

I was completely conscious. My entire body was bruised, my face unrecognizable, but miraculously, I didn’t have a single broken bone. I looked down and saw blood on my shirt, but I didn’t know where it was from. I had no shoes, no glasses, but I could stand, and I made my way into the ambulance on my own two feet, despite heavy bleeding.

Still in grave danger due to the glass and copious amounts of bleeding, I was wheeled into emergency surgery immediately upon our arrival at Maimonides Hospital. My parents, grandparents, and wife were all there: My wife, expecting our second child, had actually been two blocks away with our toddler when the building exploded, on her way to the store where she helped with bookkeeping. She ran the baby over to my mother-in-law, who lived a block over, before making her way to the hospital.

Throughout the six-hour surgery, my family waited there for news while davening desperately. When I awoke several hours later, I found out that although my wounds should have been fatal, a piece of glass lodged in my jugular vein had acted like a plug to prevent me from bleeding to death. In surgery, the doctors were able to remove the glass, staunch the bleeding, and save my life. I was lucky: The man wheeled in on the stretcher beside me could not be saved.

Afterward, I learned what had happened to the other people at the scene. My business partner was baruch Hashem okay — he’d gone to the grocery shortly before and wasn’t there when the tank fell. But unfortunately that wasn’t the case for all of our workers, as well as people who had been in the adjoining buildings or on the street. Some survivors, like me, were dug out from beneath the rubble and treated for injuries; tragically, four people died from the explosion. Two of those victims had been inside the building, but one, a 55-year-old Jewish man, was simply walking by at the time. In total, 40 people were injured, some of whom had been across the road sitting in their cars, yet I, who’d been directly in — under — the line of impact, survived.

I was hospitalized through Motzaei Shabbos. After that, I’d had enough of being incapacitated, so I checked myself out and went home. I still didn’t look great Monday morning — the bruising was awful and I was recovering from major surgery — but I walked to shul and bentshed gomel.

I felt ready to return to work within a few weeks. Our plumbing supply business was ruined and all we were left with was debt, since we had borrowed money to open it just a few months earlier. We were also facing heavy lawsuits because of the injuries and fatalities caused by the explosion. (Three years later, the charges were cleared, and the insurance money we received covered the start-up debts, so we were able to repay every penny.)

My former employers, who owned a construction company, were kind enough to rehire me for the next few years; I’m grateful to them to this day. Not only that, they also offered jobs to several of my plumbing supply store workers. Eventually, I founded my own construction company, Preferred Housing Corporation, which I comanage with my son, and I still employ the brother of a worker who lost his life in the explosion.

And every year, on the 24th of Tammuz, my family and friends and a wide circle of acquaintances know there’s an open invitation to a seudas hoda’ah marking the day my life was spared. The seudah is usually barbeque style, and we host it in our Flatbush backyard. I try to combine it with a siyum, and I speak, thanking Hashem and retelling the story. Sometimes, I show a video that a friend put together of every newscast from the day of the explosion. There are also clips of my parents and grandparents at the hospital while I was in surgery. In the summer of 2020, I was joined by several people who survived Covid in the first, intense wave of the virus; they used the opportunity to celebrate how their own lives were spared despite the severity of their illness.

The first year, when I made the seudas hoda’ah, I invited ten people. By now, I know to expect over 500 — the crowd just grew over the years, I don’t even know everyone who comes, but people hear about it, they walk in with their friends, it’s a good supper when the rest of the family is in the country — and I happily welcome anyone who attends. I’m grateful for the chance to share the story of my miracle with yet another person. Because every year, as the seudah gets bigger, so does the gratitude.

Yanky “Ziggy” Zagelbaum is the owner and CEO of Preferred Housing Corporation, a construction company that specializes in building custom houses in Flatbush and Boro Park in Brooklyn, New York.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.