An East Side Story

| April 1, 2025In the winter of 1916, amid the economic pressures of immigrant life, a dispute erupted on Rivington Street

Title: An East Side Story

Location: Lower East Side, Manhattan

Document The Buffalo Commercial

Time: 1916

IN 1870, there were about 80,000 Jews residing in New York City. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Jewish population of the great metropolis had swelled to 1.4 million, accounting for 28 percent of the city’s total population.

To provide greater context for this demographic explosion, in 1870 the total population of New York City was 942,000, of which Jews constituted about 9 percent. The total number of Jews in New York in 1914 was greater than the total population of the entire city in 1870. About a third of the entire city’s Jews were crammed into one Manhattan neighborhood — the Lower East Side.

To make ends meet in their new home, immigrant Jews engaged in all sorts of trade, business, crafts, and professions. Many were saving money to bring over their wives and children from the Russian Pale of Settlement, and sending parcels and funds to sustain their families in the interim.

Newly arrived immigrants earning as little as 50 cents a day only needed 10 cents for living expenses and could save the rest. They converted their earnings in US dollars to Russian rubles, and with an exchange rate of two rubles to the dollar, even a minimum wage job went a long way for their families back home. A single Jewish male immigrant only needed $3 a month for lodging, laundry, and a daily coffee. Bread was two or three cents a pound, and a penny would buy herring or a few apples.

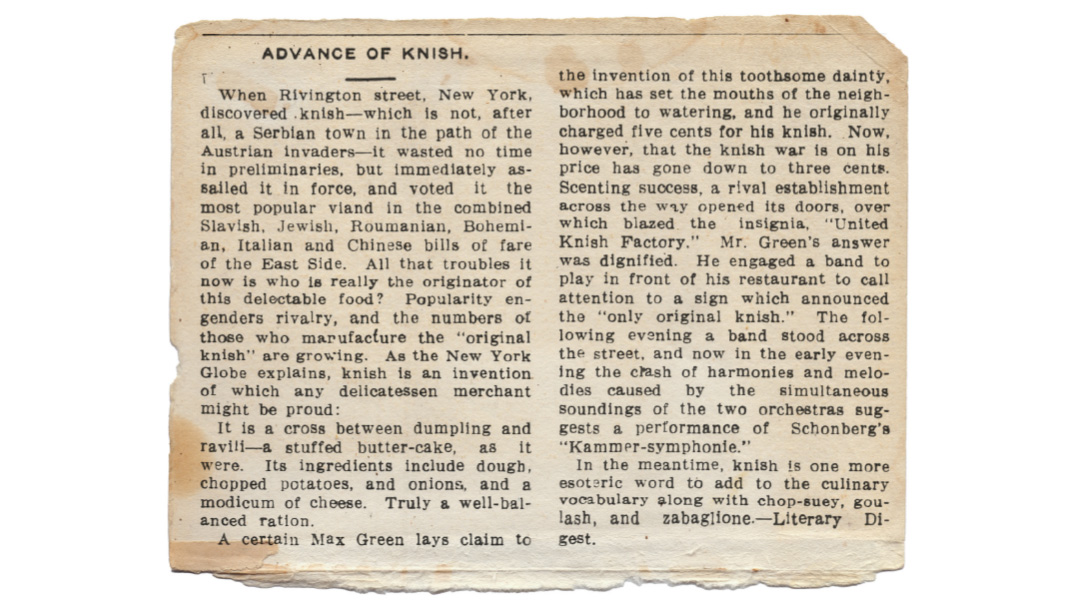

In the winter of 1916, amid the economic pressures of immigrant life, a dispute erupted on Rivington Street — not over politics, but over a baked good beloved on both sides of the Atlantic: the knish.

The episode centered around Max Green, an Austrian-born operator of a small “eating house” at 150 Rivington Street. Green had come up with a particularly appealing recipe for the traditional knish — mashed potatoes with onions and a bit of cheese, wrapped in dough and baked. Priced at five cents, the knishes quickly gained popularity among working-class patrons seeking something warm, filling, and affordable, and Green’s business prospered.

Before long, a competitor named M. London (not to be confused with socialist Congressman Meyer London) opened the “United Knish Factory” directly across the street at 155 Rivington, offering his knish for three cents. Green responded by lowering his prices and promoting his original recipe with signs and public handbills. London added a jazz orchestra outside his shop to bring in customers. Green countered with live music from a German band.

The rivalry escalated. Green began issuing coupons with each purchase that could be collected and redeemed for small prizes. According to one contemporary account, a particularly determined customer ate 20 knishes in one sitting so he could amass enough coupons for a pocketknife.

Placards were posted, musicians hired, slogans drafted — all to capture working-class customers with little money but deep loyalties to their favorite vendors. While the competition between the two men was serious, its theatrical fervor drew the attention of the press and amused the local community.

The Knish War faded from the news cycle when the United States entered World War I. Although neither of the two establishments survived, food historians credit Max Green with popularizing the knish in New York, where it remains popular today.

This column is based on the research and writings of Moses Rischin.

Knish Knosh

The knish traces its roots to Central and Eastern Europe, where a simple fried patty known as knysza gradually evolved into a dough pocket stuffed with grains or vegetables. As the potato gained prominence in the region during the 18th and 19th centuries, the knish took on a more recognizable form, baked rather than fried, and wrapped in a thin, pastry-like dough.

Ashkenazi Jews brought the knish with them to America during the great wave of immigration around the turn of the 20th century. In New York, it was well-suited to the realities of immigrant life — affordable, nourishing, and adaptable. By 1910, dedicated knish bakeries had begun to appear in the city, with Yonah Schimmel’s, founded in 1916, becoming the most enduring.

In 1921, a new variation emerged on Forsyth Street: the square, deep-fried “Coney Island knish,” designed for mass consumption and outdoor vendors. But whether served from a pushcart or a storefront, the knish became a fixture of Jewish working-class life in New York — a modest food that reflected both the resourcefulness and resilience of those who made it.

Drunk on Seltzer

How did Lower East Siders wash down their knishes? Seltzer is the likely answer. Journalist Hutchins Hapgood, a famed chronicler of the Lower East Side, noted that immigrant Jews were more likely to imbibe seltzer than alcohol. Jews were seldom seen in saloons or drunk on the streets. “The Day of Rejoicing of the Law [Simchas Torah] and the Day of Purim are the only two days in the year when an Orthodox Jew may be intoxicated. It is virtuous on these days to drink too much, but the sobriety of the Jew is so great that he sometimes cheats his friends and himself by shamming drunkenness.” —

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1056)

Oops! We could not locate your form.