An Agent in the Flesch

| December 5, 2023“It’s Shabbos Chanukah,” she responded. “And the Rabbiner will speak about the significance of this day”

Title: An Angel in the Flesch

Location: Vienna, Austria

Document: PR Material from Bais Yaakov Office in Vienna

Time: Chanukah 1914

ON 9 Av 1914, the Great War broke out, and not long after that, we were forced to leave Krakow; it was this move that led to what is now called Bais Yaakov. Along with many other refugees from Krakow, we settled in the great city of Vienna.… There was an Orthodox synagogue on Stumpergasse. Yes, that synagogue was the cradle of the movement that is now so popular — Bais Yaakov…

It was that same Shabbos morning, I think, that I first went to the Stumpergasse synagogue to pray. Before the Torah reading, I saw the Rabbiner appear at the pulpit. That was new for me.

“What’s going on?” I asked a woman sitting near me.

“It’s Shabbos Chanukah,” she responded. “And the Rabbiner will speak about the significance of this day.”

Riveted to my seat, I listened with great fascination to the fiery, spirited words of the rabbi.

In his sermon, he depicted the greatness and sublimity of the historical figure of Yehudis, and through her, he eloquently and passionately called upon Jewish women and their daughters to act according to the model of this Jewish heroine. It’s a shame that I have forgotten the beautiful thoughts and points of that sermon, and what I do remember I lack the eloquence to convey on paper.

There is one thing that I cannot forget. Even as I was caught up in the spiritual description of the character of Yehudis, it occurred to me: Ah, if only all those women and girls in Krakow were here now to learn who we are and where we come from. It struck me that our major problem is that our sisters know so little about our history, which alienates them from our people and its traditions. If only they knew of our holy martyrs, or had the slightest grasp of the heroism of our great men and women — things would be entirely different. …

After that first sermon by Rabbi Flesch, I became a regular visitor at the Stumpergasse synagogue. Nothing could stop me, neither terrible weather nor the frightful tumult of wartime. I unfailingly attended Rabbi Flesch’s lectures on Tanach, Tehillim, Pirkei Avos, and his profound meditations on various issues of the day. The more I learned, the more I was haunted by the question of how I could bring this knowledge to the Jewish girls of Poland, so they could hear and know the things that I was learning.…

—Collected Writings of Frau Sarah Schenirer; translated by Dr. Naomi Seidman

ON Shabbos Chanukah 1914, the Bais Yaakov movement was born. A chance encounter between a young Sarah Schenirer and Rav Moshe David Flesch eventually led the former to establish the original Krakow Bais Yaakov shortly after her return home during World War I. What was so compelling about the message delivered by the Pressburg-born rabbi to the refugee from Krakow on that frosty Chanukah morning?

Yes, the narrative related by the rabbi involved the heroine figure of Yehudis, whose clever initiative against the Greek general Holofernes saved the Jewish People during the Chanukah story. Yehudis clearly was an inspiration for Sarah Schenirer, who sought to save the Jewish People spiritually by leading girls back to Torah observance. But it’s hard to imagine that the well-read autodidact wasn’t already familiar with the Midrashic tale of Yehudis, even prior to Rabbi Flesch’s impassioned account. Furthermore, by her own reckoning, she was unable to recall the details of the sermon, so the content alone would not be a sufficient impetus for the establishment of a worldwide educational system.

There was something about the delivery itself, the fact that Rabbi Flesch was directly addressing the women of the community, casting them in the role of Yehudis, and imploring them to act on behalf of the spiritual survival of the Jewish People that struck Sarah Schenirer as so unique. The Frankfurt-educated rabbi carried the method and ideology of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, with tradition and modernity working in tandem to realize the goal of spiritual growth and flourishing Torah observance. In the chassidic Galicia of her youth, this was an unfamiliar concept. What she discovered in Vienna and sought to bring back with her to Krakow was a way to convey a traditional message in the form of a modern expression and outlook.

The purveyor of this message was Rav Moshe David Flesch (1879–1944). Born into a rabbinic family in Pressburg, he entered the city’s prestigious yeshivah, where he became a student of the Chasam Sofer’s grandson Rav Simcha Bunim Sofer, the Shevet Sofer. In 1906 he headed west and studied in the Frankfurt yeshivah of Rabbi Dr. Solomon Breuer, who had succeeded his father-in-law, Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, in the rabbinate of the separatist Orthodox community of Frankfurt.

Along with his Pressburg upbringing, Rav Flesch soon became an adherent of Rav Hirsch’s religious philosophy and would incorporate many of its precepts in his own teachings. Though he had seemingly migrated metaphorically from west to east, it’s interesting to note that Rav Breuer himself made the exact same journey. Having grown up in Hungary, he too had studied in Pressburg under the Ksav Sofer before marrying Rav Hirsch’s daughter and assuming the rabbinate of his father-in-law upon his passing in 1888.

After serving short rabbinical stints in several small Vienna shuls, Rav Flesch married into a wealthy Vienna family in 1913 and was subsequently hired to serve at the helm of the prestigious Stumpergasse shul, a position he held until the shul’s destruction during Kristallnacht in November 1938. Situated in Vienna’s upscale Seventh District in a courtyard on 42 Stumpergasse, the shul was established in 1893 as a subsidiary of the prestigious Schiffschul in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt Second District. The Stumpergasse shul followed Hungarian Oberland Orthodoxy, though its congregants were generally wealthier and more integrated than those of the Schiffschul. The shul ran an afternoon Talmud Torah in an adjacent building where the local children studied after school.

Rav Flesch’s tenure revitalized the community, and he injected an urgency into strengthening Torah observance and Jewish education. A talented orator, his pulpit sermons drew many non-Shabbos-observant members to the shul and drew them closer to religious commitment. He delivered many Torah shiurim to adults — both men and women — and delivered daily classes to the older children of the Talmud Torah. Both the shul and Talmud Torah expanded during the 1920s.

The shul’s activities were curtailed, but not ended completely, as a result of the Anschluss with Nazi Germany in March 1938. During the early morning hours of November 10, the Stumpergasse shul fell victim to Kristallnacht when local Nazis burned the shul to the ground. Eyewitnesses noted that firefighters hosed down adjacent structures to prevent the flames from spreading, but nothing was done to prevent the synagogue from burning. That very day, the Gestapo arrested Rav Moshe David Flesch. His release was conditional on him leaving Vienna, so he and his family quickly escaped to Holland.

The Nazis caught up with the Flesch family following the occupation of Holland in the spring of 1940. With an eye toward the future, Rav Flesch arranged conditional gittin in Amsterdam to alleviate potential agunah issues arising from the war. In the autumn of 1943, Rav Flesch was arrested and sent to the Westerbork transit camp. Suffering from Parkinson’s disease, he was deported to Buchenwald, where he was further weakened from malnutrition and disease. At age 64, in March 1944, he succumbed to his illness and died, Hashem yikom damo.

Perhaps the most enduring element of Rav Flesch’s legacy was his creation of the ideological framework for the establishment of Bais Yaakov, through his teachings as heard by Sarah Schenirer. His words contributed significantly to the development of her vision.

It commenced with Shabbos Chanukah in December 1914, but by no means was this a one-time interaction. Rav Flesch followed a custom instituted by the Chasam Sofer and adopted by Oberland kehillos such as the Schiffschul of eulogizing tzaddikim who had passed away the previous year each 7th of Adar. On that date in 1935, Rav Flesch veered from his general custom and delivered a hesped for a woman tzadeikes, Sarah Schenirer, who had passed away just two weeks earlier.

He shared with his audience how more than two decades earlier, a young Sarah Schenirer had attended the Stumpergasse shul on a daily basis for Shacharis and remained for his daily Pirkei Avos shiur. Listening attentively from the ezras nashim, she took meticulous notes, and continued this practice for several months during her stay in Vienna. These handwritten notes subsequently formed a central component of her curriculum in the initial stages of Bais Yaakov, in her own classes and later throughout the movement.

In 1932, Rav Flesch traveled to Poland to visit his son who was studying in the yeshivah in Tchebin. Sarah Schenirer took the occasion to invite him to Krakow and give him a guided tour of the Bais Yaakov seminary so he could see his “spiritual child,” as she referred to it. Shortly before her passing, she visited Rav Flesch in Vienna once more.

Though Rav Flesch and the Stumpergasse shul didn’t survive the Nazi onslaught, all of his children miraculously survived the Holocaust, and his descendants have published some of his Torah works. The continued growth and flourishing of Bais Yaakov and girls’ Torah education worldwide is perhaps the crowning aspect of his legacy. In a modern-day Chanukah miracle, the light that was lit by Rav Moshe David Flesch in the heart of Sarah Schenirer in the Stumpergasse shul of Vienna so long ago burns brighter than ever in hearts and minds all over the world.

All Roads Lead to Vienna

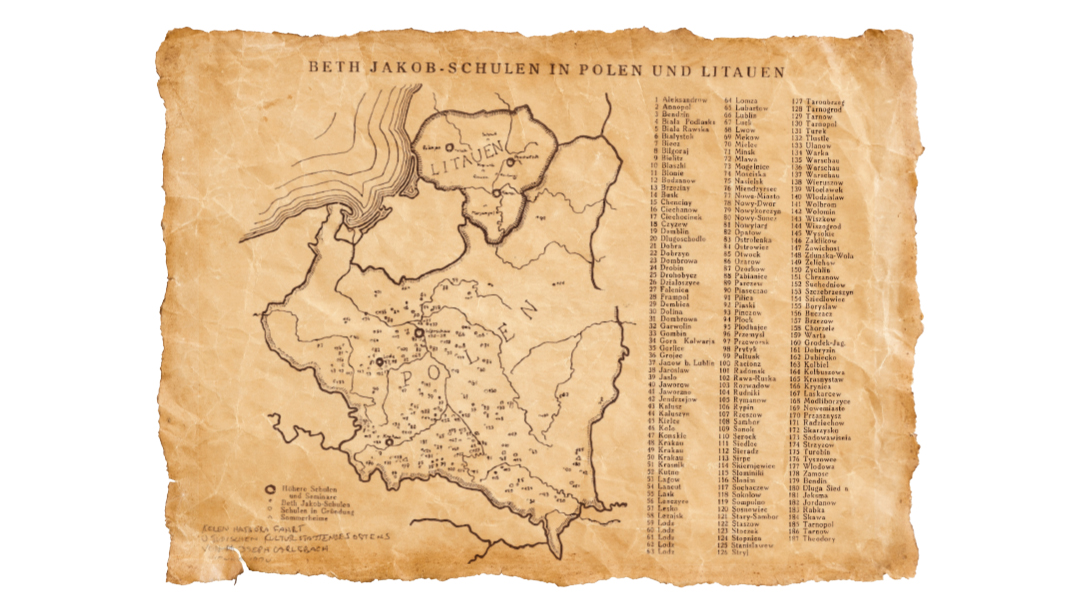

Just a few years after Sarah Schenirer’s Vienna sojourn, Dr. Leo Deutschlander settled in Vienna. A talented pedagogue, he soon assumed a leading role in the World Agudath Israel, and in that capacity took managerial and fiscal responsibility for the entire Bais Yaakov movement. Though Krakow was the birthplace and nerve center of Bais Yaakov, Vienna served as its administrative headquarters. The first Bais Yaakov opened in Vienna in 1920, and in 1930 it already had its own teachers’ seminary, similar to the one in Krakow. As fate would have it, Leo Deutschlander was a member of the Stumpergasse shul and maintained a relationship with Rav Moshe David Flesch.

A Meeting of East and West

When Sarah Schenirer asked Rav Flesch to recommend seforim for inspiration, he suggested the works of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch and Rav Marcus Lehman. Their works ultimately had a decisive impact on her outlook and vision for Bais Yaakov, especially those of Rav Hirsch. She was especially influenced by his philosophy of Torah im derech eretz, and galvanizing tradition in order to face the challenges of modernity.

Dr. Judith Rosenbaum-Grunfeld, who served as Sarah Schenirer’s assistant and one of the primary educators of prewar Bais Yaakov, stated that Rav Hirsch’s Chorev and The 19 Letters served as core curriculum reading material for Bais Yaakov faculty and students in the interwar years. Sarah Schenirer also visited Frankfurt and interviewed members of Rav Hirsch’s family in order to find out more about his life and ideals. Dr. Isaac Breuer once recalled about meeting Sarah Schenirer, “She declared that my grandfather’s sefer Chorev inspired her to establish Bais Yaakov.”

The extensive research and writings of Dr. Naomi Seidman, Rav Moshe Leventhal, and Batsheva Levi were utilized in the preparation of this article

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 989)

Oops! We could not locate your form.