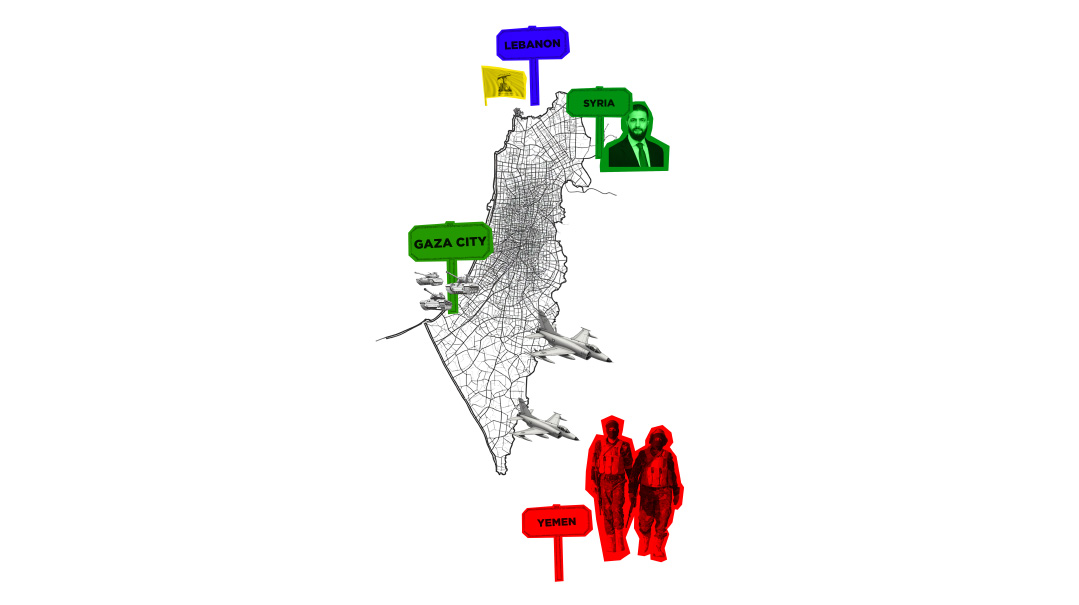

Across the Firing Line

Among the most vocal critics are the tens of thousands of evacuees from communities near the Lebanese border

Photos: Flash90

Although the announcement of a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah garnered international favor, particularly with the United States and Europe, for Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s government, it has stirred a cauldron of controversy on the domestic front. The center-right factions that form the bedrock of Netanyahu’s electoral support are raising a chorus of discontent, while security analysts insists a ceasefire is currently the only viable option.

Among the most vocal critics are the tens of thousands of evacuees from communities near the Lebanese border, who had been holding out for a different kind of resolution.

Avichai Stern, the mayor of Kiryat Shmona, a city perched on the Lebanese border, doesn’t mince words in speaking to Mishpacha. “This agreement brings us closer to the next October 7 in the North. And to my great sorrow, what Hezbollah planned to do a year from now will now be carried out in ten. But they’ll do it, because we haven’t learned a thing.”

Stern’s frustration is palpable. “The residents of Kiryat Shmona feel abandoned,” he says. “For over a year now, we’ve endured the situation quietly, despite the less-than-ideal conditions, without complaint. We were promised a different reality, a safer one. Now we’re expected to return, but nothing has changed. We’re going back to the same precarious situation we left behind more than a year ago.

“I’m not denying that significant damage has been inflicted on Hezbollah, and I’m not taking that achievement away. But give it a year or two, and they’ll rebuild. So, what’s different now? If people in Gaza are still prohibited from returning to border areas, why should we return in the North? We know what’s waiting for us on the other side of the border. We’ve lived it.”

Not everyone, however, is opposed to the ceasefire. Some experts see it as not only a rational decision but an essential one.

“The ceasefire isn’t just beneficial — it’s necessary,” says Ofer Shelah, a former MK and current director of the Israel National Security Policy research program at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Tel Aviv, speaking to Mishpacha. “What matters most is stopping the fighting, not what’s written in the agreement. The specifics of the document are secondary. It’s not a legal contract that people will litigate over for years. The important thing — and this is something we’ve learned from past agreements — is what happens after it’s signed.”

Shelah insists the ceasefire is necessary now because the current round of fighting has effectively played out. “In essence, the agreement signals that both sides want the current situation to end, mainly because neither sees any benefit in continuing,” he says. “The reality is that both sides have concluded it’s in their best interest to stop fighting. Now we enter a new phase, and in that context, the agreement’s written terms are irrelevant. For instance, Israel conducted an operation in Lebanon even after the agreement was signed.”

Checking Children’s Bedrooms

Since the government ordered the evacuation of northern towns, some 90 percent of Kiryat Shmona’s nearly 25,000 residents have been scattered across the country, relocated to 560 settlements and 320 hotels. Avichai Stern, who describes himself as the “father of 25,000 people,” is clear about what he wants the government to do.

“There needs to be a security buffer — a zone of three kilometers, maybe five — where no one can enter,” he asserts. “Otherwise, someone will come along tomorrow, build what looks like a house, but it’s not a house. It’s a weapons cache, hidden among civilians, with the sole purpose of attacking Israeli citizens. They’ll stash weapons in children’s bedrooms, and at the moment they choose, they’ll strike. That will be our next October 7.”

Stern is impatient with arguments that it’s in everyone’s interest to stop the fighting now.

“With all due respect to those now signing this agreement, they’ll be replaced in a year or two by someone else,” he argues. “The military commanders, the officials responsible for northern security — they rotate every two years. But we’ll still be here. Thirty years from now, fifty years from now, we’ll still be here. I want my children to grow up here and stay here. But who guarantees anything? What happens then?”

“I believe the army when they say they’ll push Hezbollah forces back. But do Hezbollah operatives walk around with ‘Hezbollah’ stamped on their foreheads? The people attacking us are civilians in their homes — families with children! They keep their kids in their beds, and right there in the same room, they store their missiles! That’s how terrorist organizations operate, they embed themselves within civilian society. No one — not you, not me, not even the United Nations — can prevent that. Are we going to check every child’s bedroom? That’s the fundamental difference between us and them.”

When asked about the northern residents’ criticisms, Ofer Shelah is empathetic. “I completely understand their position,” he admits. “They have every right to voice their frustrations. After all, the state evacuated them over a year ago, and they deserve to return to their homes.

“But it’s important to recognize that anyone who believes it’s possible to create a reality without threats from Lebanon is misreading the situation. Israel doesn’t have the military or diplomatic capability to achieve that.”

Shelah is just as adamant as Stern about the road to a solution in the North — but he advocates a different path.

“What needs to be done is threefold,” he asserts. “First, implement a defense system that residents can see and feel — something that offers as much assurance as possible that another October 7 won’t happen, though that doesn’t mean missiles won’t fall. Second, invest in rebuilding the North’s economy, which has been deeply affected since October 7. And third, take aggressive action to prevent Hezbollah from approaching the border again. That’s what’s achievable.”

He is dismissive of any call for creating a buffer zone inside Lebanon three to five kilometers deep. “Anyone who believes Israel can militarily subdue Hezbollah or create a security belt inside Lebanese territory simply isn’t reading the situation correctly.”

Thick and Thin

One of the most painful aspects of the current reality for Kiryat Shmona’s residents is the feeling that their loyalty to the ruling coalition has paid no dividends. They have stood by Netanyahu’s government through thick and thin, defending it against harsh criticism. Yet Stern left a recent meeting with the prime minister feeling profoundly let down.

“We met with the prime minister, and it was a disgraceful performance from the outset,” he recounts. “But we listened. I asked, ‘How will you protect us if they store missiles in their children’s rooms?’ I got no answers.

“We want our enemies to think twice before attacking Kiryat Shmona, just as they do before targeting Haifa. We’re right-wing voters, and we voted for this government. They promised us a strong right-wing leadership, and they haven’t delivered on that promise.”

Stern tells Mishpacha that if the government orders northern residents to return home, he will not only oppose the decision but also actively encourage his constituents to resist. “I don’t just think people won’t want to return — I’ll do everything in my power to ensure they don’t,” he says. “The risk of another October 7 hasn’t been eliminated. Going back now would be walking into a potential massacre.

“And I’m not alone in thinking this. Any mayor in the North, anyone who knows the reality of living near the border, thinks exactly as I do. There’s no debate. The shocking thing is that, until now, only we understood this. Now the whole country knows what’s on the other side. We all have to say birkat hagomel because we’re still alive.”

Ofer Shelah points to Israel’s significant military achievements in Lebanon but dismisses the idea of eradicating Hezbollah as unrealistic. “In Lebanon, we’ve achieved notable successes. Hezbollah has suffered considerable damage. But that damage won’t destroy them or make them surrender. Anyone who believed that was possible was fooling themselves.”

Shelah says the situation in the North has deteriorated to its current state due to the failures of past agreements, such as UN Resolution 1701, signed in 2006 to end the Lebanon War, which Hezbollah subsequently violated. He insists the proper course of action lies in enforcing Israel’s security, not adhering to the fine print in the current ceasefire agreement.

“The big question isn’t the agreement itself but whether Israel will make decisive, practical moves to prevent Hezbollah from rearming and approaching the border,” says Shelah. “That’s where Resolution 1701 failed. Ultimately, that’s all that matters — Israel’s unwavering resolve to prevent any Hezbollah advances in the region, not the agreement’s text.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1039)

Oops! We could not locate your form.