A Word from the Wise

| September 12, 2023Daas Torah can often surprise us, but the answers to our questions are often clearer than we could have imagined

Photos: Meir Haltovsky, Flash90, Mattis Goldberg

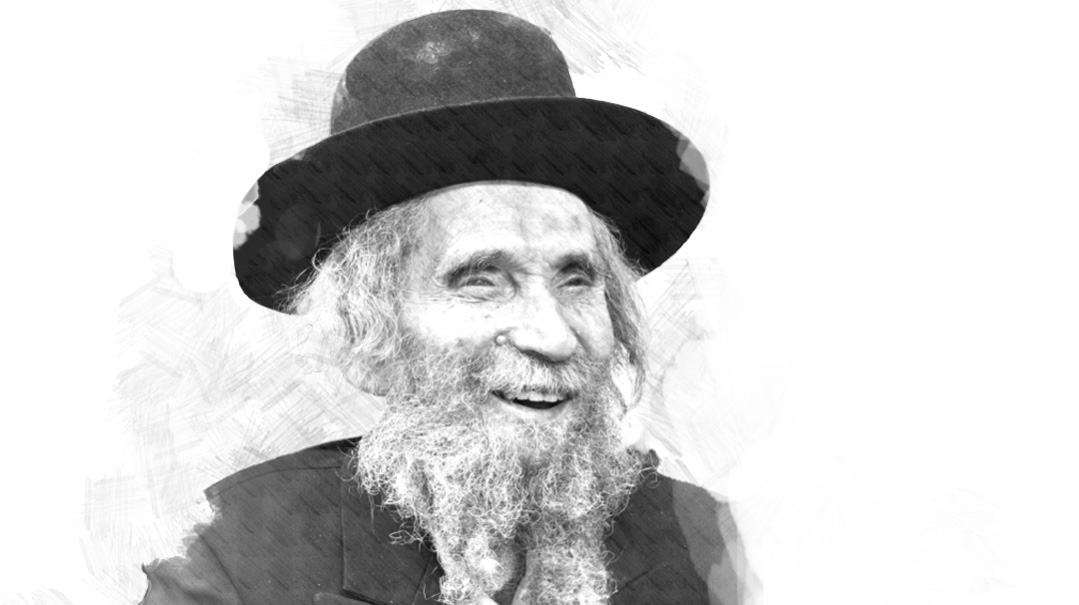

Never Say No

Rav Pam was too weak to walk down the stairs, but that didn’t stop him from fighting for another school with the strength of a lion

Thirty-three years ago, RAV AVRAHAM PAM, rosh yeshivah of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, founded the Shuvu movement, cultivating and cherishing it like a precious child for the remaining ten years of his life. I had the zechus of working under Rav Pam for those ten years, directing Shuvu and bringing his dream to life by providing a Jewish education to the children of Russian immigrants here in Eretz Yisrael.

In those years, we had two main annual fundraising events in the States, a dinner in the winter, and a parlor meeting in the summer. Every summer, I would prepare a detailed report on the Shuvu network and send it as a letter to Rav Pam, and he would then use it to describe the situation to our supporters at the parlor meeting.

During the last year of Rav Pam’s life, the financial situation of Shuvu was precarious, and I shared the numbers and details with Rav Pam. I also wrote him that we had received a petition from over 100 parents in the town of Natzeret Illit (today called Nof HaGalil) asking us to open a Shuvu school. “We will be forced to say no,” I wrote. “There is no way we can take upon ourselves to open another school. It is not feasible.”

Those who were with Rav Pam on the night of the parlor meeting told me that he was so weak, it took half an hour just to walk down the steps of his house in order to attend the meeting, which was held at the home of Rabbi Gedalia Weinberger in Flatbush.

At the event, Rav Pam took my letter and started to read it out loud to the donors gathered around the table. He reached the line “we will be forced to say no,” and stopped reading. Then he turned to the others and told them, “There is no cheshbon in the world that can force us to say no! How will we live with ourselves? How will we make bar mitzvahs and bas mitzvahs for our own children if we deprive these parents who have come from Russia and are begging us… they will not be able to make bar and bas mitzvahs for their children. There is no cheshbon in the world.”

With his remaining strength, Rav Pam banged on the table. “Yes, there will be a school in Natzeret Illit, and the Shechinah will rest on that school.” Then Rav Pam looked at the tzibbur and said, “I hope you will back up my decision.”

In the end, we opened up a Jewish school for the immigrant population. It was tough, it was a big headache, but the donors generously responded to Rav Pam’s plea and helped us out.

Twenty-three years after that parlor meeting, when war broke out in Ukraine, the Israeli government settled some of the new refugees right there in Nof HaGalil. Our doors were open wide to their children, and we filled our classes to capacity. I know for a fact that if our Shuvu school was not there, these Ukrainian Jewish children would be in secular schools. We make bar and bas mitzvah celebrations for the children in Nof HaGalil and in all our Shuvu schools, and, as Rav Pam said, with those merits, may we celebrate our own children’s growth in mitzvos.

This week I spoke with the Shuvu principal in Nof HaGalil, who told me she has 40 new families of Ukrainian children in attendance. They are there, learning Torah in a frum school that was already well-established and just waiting for their arrival — and according to Rav Pam, the Shechinah was waiting too.

Rabbi Chaim Michoel Gutterman is the director of the Shuvu school network.

You’ll Do It Your Way

By Reb Abish Brodt

When the Rachmistrivka Rebbe told me to pass on the concert, I accepted, but didn’t understand. Soon enough, his purity of vision became clear to me, too.

Meeting Reb Shmuel Brazil so many years ago was a gift from the Eibishter. A truly ehrliche Yid, a maggid shiur, and a talmid of Rav Shlomo Freifeld, Reb Shmuel was also a composer whose songs were real music and worth singing. We’d get together to sing, and people waited to hear Reb Shmuel’s songs. After many requests for us to record them professionally, we paid attention — creating the first Regesh albums in the 1980s. I was close to 30 years old at that time.

Right after the first album was released, I got a call from Rabbi Moshe Sherer of the Agudah. At the time, Russia was still the Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain was firmly in place, but Jewish organizations had been able to organize some Jewish concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Yigal Calek was going to perform for Russian Jewry with his London School of Jewish Song, and Rabbi Sherer wanted to know if I would also get up on stage to sing, offering the audience chizuk through music. He needed an answer within 36 hours so that a visa could be issued by the Russians in time.

I didn’t know what to do. From the outset, Reb Shmuel and I recognized that we didn’t want to become entertainers, and therefore we had set ourselves certain gedarim, boundaries, including not performing live on stage. We did this for our own sakes as well, but mainly, we did it for the sake of our children and their chinuch. Obviously, though, this event was not just entertainment: It was for the sake of a mitzvah, for kiruv purposes, a chance to reach out to Yidden locked up in Communist Russia. I told Rabbi Sherer I would get back to him, and off I went to speak to the RACHMISTRIVKA REBBE of Boro Park ztz”l, Rav Chai Yitzchok Twersky.

I explained the stricture we’d taken upon ourselves, and my current dilemma. First of all, the Rebbe didn’t know what a modern concert was all about. “Vus is dus?” I explained what it entailed, and he also called in the gabbai to clarify it. Then the Rebbe said that he had to think about the question.

I left his presence, aware that I was under pressure for the answer, but happy that I had left the matter in the hands of a heiliger Yid. The Rebbe called me the next day. “Abish, Ich halt az di zolst nisht gein. A tzveiter zohl es tin. Di zolst tin auf daineh oifen [Abish, I think that you shouldn’t go. Someone else should go, and you will do it in your own way].”

What did the Rebbe mean, I would do it in my own way? Until that point, I had never thought of going to Russia at all. How? For what? But these were my marching orders.

It happened. That summer, another opportunity knocked. The Vaad LeHatzolas Nidchei Yisroel arranged a trip to Riga, Minsk, Vilna, and Moscow for four participants, and I was able to go. Our group was in the USSR for two unforgettable Shabbosos, and we had incredible hatzlachah.

We joined groups of Russian Yidden who were on “dacha,” a kind of rural retreat. They knew next to nothing, but they wanted to learn everything, about brachos and Shabbos, anything they could, and we learned with them and sat and sang with them. Those Yidden went very far, some of them becoming choshuve talmidei chachamim and roshei kollel. I remember one young person who was there with a ponytail, and today he’s a long-time avreich in Yerushalayim.

Baruch Hashem, the mission had tremendous impact and influence. I went on additional missions to Russia together with the Novominsker Rebbe ztz”l and yblch”t Rav Mattisyahu Salomon, in which we saw tremendous success. And, as the Rebbe predicted, we did it in our way — no concert, no stage performance, just singing together with other Yidden.

Now, after the shivah of this holy Yid, I can share the story and marvel at what he was able to see.

Reb Abish Brodt, the voice behind Regesh, is a veteran baal tefillah and baal menagen.

Our Shared History

By Avi Shulman a”h

Would an irate father let his daughter live a frum life far away from home?

Many years ago, I had arranged to travel to Mexico as part of a SEED program I was involved in, and before I left, a Yid in Monsey called. He said he’d received a call from a Mexican Jewish girl. She was a 15-year-old who had become frum and could not remain in her parents’ non-kosher home. She wanted to live with a frum family and was interested in working as a mother’s helper for a family in Monsey and attending Bais Yaakov. He wanted me to check it out.

I met with the Mexican girl while I was there and reported to the fellow in Monsey how sincere she was. The move was soon arranged. She came to Monsey where she lived with a family, went to school, strengthened her Yiddishkeit, and made friends. Everyone was happy — except the girl’s father, who had originally allowed her to move, but soon changed his mind.

The father began to call his daughter and pressure her to move back to Mexico. Then he started to call the family she was staying with, harassing them. Eventually, he came up with an ultimatum: If his daughter was not sent back home to Mexico in three days, he would call the FBI and report her “kidnappers.”

The host father was very nervous, and he called me. What should they do? I called RAV YAAKOV KAMENETSKY and we set up a meeting. The girl was invited, too. We sat down, and Reb Yaakov asked her to tell her story. She explained her background, relating that her father was a secular Russian and had no interest in religion. She, however, wanted to live a frum life like that of the families she’d gotten to know in Monsey.

Rav Yaakov said to her, “Your father came from Russia. Tell me, which city did he come from there?”

She gave the name of a small town, and Reb Yaakov commented, “My train passed through that town, so your father and I are landsleit.”

The Rosh Yeshivah then asked for a piece of paper, took out a pen, and wrote a warm letter in Yiddish. “Dear Father, your daughter is here… we are landsleit, we have a shared history…. Today we are living in a different world from what we were used to, and we have to be more open and accommodating with the younger generation’s needs and wants….”

He signed it just “Yaakov,” and told me to go to the airport and find someone traveling to Mexico.

The letter made its way to Mexico, and the father soon called his daughter. “A man just brought me a letter from some rabbi, and he says I should leave you to it. Okay, you know what? Just stay there.”

Avi Shulman, who passed away in November 2022, was a life coach, rebbi, and founder of Torah Umesorah’s project SEED. This is part of an unpublished interview he gave Mishpacha before his petirah.

How America Works

By Rabbi Nosson Yaffe

WE wanted to go after the gvirim, but Rav Steinman told us to rely on the klal

In 2003, we began to fundraise in America for Kupat Ha’ir, Israel’s largest volunteer-based charity fund. It was RAV AHARON LEIB STEINMAN ztz”l who told us to open up shop there, because hard times were coming. I told the Rosh Yeshivah that as I’m an English boy, it would be much easier for me to work on fundraising in the UK or France first. I traveled there and set things up, but the Rosh Yeshivah reiterated the need to work in America, so America it was.

Kupat Ha’ir is big. To give you some idea, it has 130 secretaries, and 18 social workers employed to check the families’ needs and circumstances before priority eligibility is decided by the dayanim. Since it is not a mosad with an internal budget, the cash flows in and then directly out. The organization’s goals are to cover the most basic needs for impoverished families, whether medical or simply basic clothing, tuition, and food.

In Eretz Yisrael, our mode of fundraising, which was original back when we opened, involves giving out flyers and placing ads in newspapers. We publicize people’s difficult stories, and Yidden read and donate. But America was different, and we didn’t know how to do it. Should we meet individually with potential donors who would help carry the burden, or perhaps take a different approach, such as dinners and parlor meetings?

We went in to Rav Aharon Leib with our plans. The Rosh Yeshivah was not on board. “Don’t only run around to the gvirim. You have the paper advertisements. You are successful in Eretz Yisrael. You do the same in America. Let people know about the need, and whoever has the zechus to give will give.”

He didn’t want us to approach key individuals for major donations? To rely on Klal Yisrael as a whole for both the big and small donations? We listened. People thought we were crazy, because “that’s so Israeli, that’s not how America works.”

We keep our expenses as low as possible, so we printed the Chanukah flyers in Eretz Yisrael before Succos and shipped them to America. We had to hire one yungerman there to work for us, to process the receipts. He was so skeptical about anyone donating that when he bought a laptop for Kupat Ha’ir, he verified with the store that if it was unused in the box, he could return it.

Soon, though, he was printing receipts.

Five years after we began to operate in the US, the economy crashed. So many gvirim lost their footing. The institutions that had relied on their major donors there went into financial freefall, as donors who used to support them with tens of thousands of dollars a year called in regretfully to say they weren’t able to continue.

Kupat Ha’ir did not have those connections to those donors, and suddenly we saw what Rav Steinman had in mind. We were not relying on a few dozen people, we were relying on the goodness of the hearts of Klal Yisrael, and therefore, we continued to get both big and small donations from tens of thousands of people, and the source did not dry up.

People told us, “that’s not how America works,” but they didn’t understand that the Ribbono shel Olam makes America work according to what the gedolei Torah say.

Rabbi Nosson Yaffe is international senior representative for Kupat Ha’ir.

Far from Home

By Rabbi Joey Grunfeld

How could I keep up a spiritual level so far away from my Torah base? The Steipler gave me a hint

I was learning in Gateshead Kollel in 1979 when we established SEED in the UK, and I was asked to lead it. Although working in kiruv rechokim was a natural fit for me, Gateshead was a special Torah experience, and I didn’t want to leave it. I always say that Gateshead Kollel was like the Jewish version of Cambridge University — the kollel men were of a very high caliber, and the program, established by Rav Dessler, extremely rigorous: Sunday and Monday were for a quick limud of a chosen masechta; from Tuesday until Thursday afternoon everyone changed chavrusas and learned the same material again, with more depth, and on Thursday afternoon, Friday morning and Shabbos morning after kiddush, they switched to a third chavrusa and learned a different masechta.

I wound up spending most of the week in London, working in kiruv for SEED, but my family lived in Gateshead, and I made sure to be back for Thursday afternoon so that I could still be part of the kollel for the third seder. I did this for 18 years, finally relocating the family to London.

During that time, I was away from my family most of the week, although always back for Friday and Shabbos, and naturally, I was worried about how this would affect my children and my connection to them. Rav Mattisyahu Salomon was the mashgiach in Gateshead then, and after I discussed this at length with him, he told me to ask for advice from the STEIPLER GAON in Bnei Brak.

At that time, the Steipler was already older and was hard of hearing, so the question had to be written out. Rav Mattisyahu wrote the letter describing my situation for me, because he had a connection with the Steipler and knew how to explain it, and the next time I was in Eretz Yisrael, I arranged to go in to the Steipler on a Motzaei Shabbos. The Steipler read Rav Mattisyahu’s note and said he understood my concern — this situation could indeed be a problem.

His advice was that when I was back in town, over Shabbos, I should make sure to create a kesher with my boys by investing the time to sit down and learn with them and that we should learn the sefer Orchos Tzaddikim together. I followed his advice and learned through the entire sefer twice with my sons.

I also confided that I was worried about my own ruchniyus, since I was constantly exposed to unaffiliated Jews and students, as well as others who hung around in London.

At that, the Steipler jumped up from his seat, and brought down the sefer Ha’amek Davar.

He went to the shelf to get the sefer and showed it to me inside, in the Harchev Davar commentary. The Netziv discusses Yosef Hatzaddik naming his son “Menashe,” because, as the pasuk says, “ki nashani Elokim es kol amali — Hashem has made us forget all my hardship.” But really he should have said “es kol anyi.” The Midrash says that amali, which literally means “work” or “effort,” here refers to the Torah. Why would Yosef name his son in thanks for forgetting his Torah learning?

The Netziv answers that Yosef was busy with Potifar, was learning less, and began to forget his Torah, and he was upset about this. But once he started helping with the needs of the tzibbur, which the Midrash says is equivalent to learning Torah, then Yosef was able to celebrate by naming a child after this forgetfulness, since he would not be held accountable for the Torah he’d forgotten while helping the tzibbur.

The message hit the spot. If I was working for the tzibbur, I didn’t need to mourn the time lost from learning.

Rabbi Joey Grunfeld is a British outreach pioneer and founder and director of SEED UK

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 978)

Oops! We could not locate your form.