A Token of Appreciation

| January 6, 2026I was starting to feel a bit desperate, until I suddenly remembered that historical precedent was on our side

Photos: AbstractZen

E

lected officials don’t like to play around with bribery, and Sheriff Chronister of Hillsborough County, Florida was no exception. He shook his head, eyes narrowed suspiciously, when I showed up at his office to offer him money. The “favor” I was paying for? Bringing the Tampa eiruv into existence. The amount I was paying? One whole dollar.

Sechirus reshus (literally, “renting permission,”) is an important component of the eiruv-building process. An eiruv turns public property and other people’s private property all into one big private domain (halachically speaking), where Jews can carry on Shabbos as if inside their own homes. The mechanism for this magical transformation from public property to private is the sechirus reshus — a rental agreement where the Jews of the city lease the public property from a city official for a nominal amount of money. The public official who conducts this rental must be someone who has the authority to enter into all areas of the city, which in most cases, is the mayor, police chief, or county sheriff.

Which is why I was doggedly trying to talk Sheriff Chronister into taking my money on behalf of Tampa’s Jewish community, and he was just as resolutely refusing. No amount of halachic reasoning (“But the whole eiruv won’t be usable without this payment!”) or logical reasoning (“It’s only a dollar!”) could convince the straightlaced sheriff to put his job on the line. I was starting to feel a bit desperate, until I suddenly remembered that historical precedent was on our side.

Tampa wasn’t the first Jewish community to confront a reluctant public officer. In 1979, Rav Moshe Heinemann of Baltimore and Dr. Bert Miller were building the Baltimore eiruv, one of the first city eiruvin to be constructed in the United States. They, too, faced a mayor who adamantly refused to accept payment from the Jewish community in order to complete the sechirus.

I smiled to myself as I remembered their innovative resolution. Rav Heinemann and Dr. Miller announced that the Jewish community would be honoring the mayor. Just weeks later, a delegation from the Baltimore Eruv Committee appeared at City Hall. Amid flowery speeches, the mayor was presented with an elegant plaque, inscribed with the text of the sechirus. The mayor proudly accepted his honor, all while admiring the beautiful silver dollar coin decoratively mounted at the bottom of the plaque. “This ceremony is very meaningful to me,” he said emotionally. “It represents a community that continues to uphold its three-thousand-year-old values.”

Wondering if this tactic could possibly be revisited 45 years after its debut, I rushed out of the sheriff’s office, already dialing Rabbi Jeremy Rubinstein, Dean of Tampa Torah Academy and head of the Tampa eiruv project. “We need a customized plaque, pronto. We’re going to give Sheriff Chronister an honor he can’t refuse!”

In a matter of weeks, our rush-order award was promptly delivered and adorned with a silver dollar. Rabbi Rubenstein headed over to the sheriff’s office with the plaque in his hand and a tefillah on his lips.

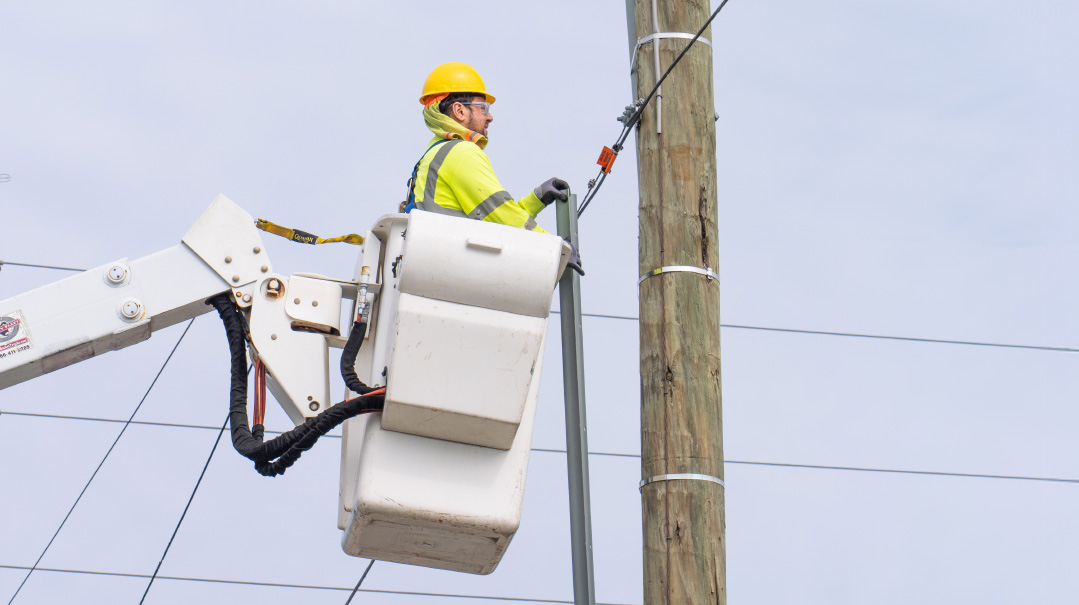

Twelve hundred miles away and high up in the bucket of my cherry-picker truck, I felt my phone buzz. Smiling up at me from the screen, against a backdrop of American and Floridian flags, Rabbi Rubenstein and the sheriff grasped the familiar black and gold plaque. The sheriff looked happy, if a bit confused, about this unexpected honor, but Rabbi Rubenstein looked absolutely ecstatic that our little scheme had worked. Thanks to the sheriff’s acquiescence, the Tampa eiruv was officially up and running.

I, too, was pleasantly surprised by the success of our covert operation. But, I reflected, I should have known it would work. Bribery may get you nowhere, but a token of appreciation always paves the way to cooperation.

*Names and identifying information changed to protect privacy

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1094)

Oops! We could not locate your form.