A Short Story, Not a Sad One

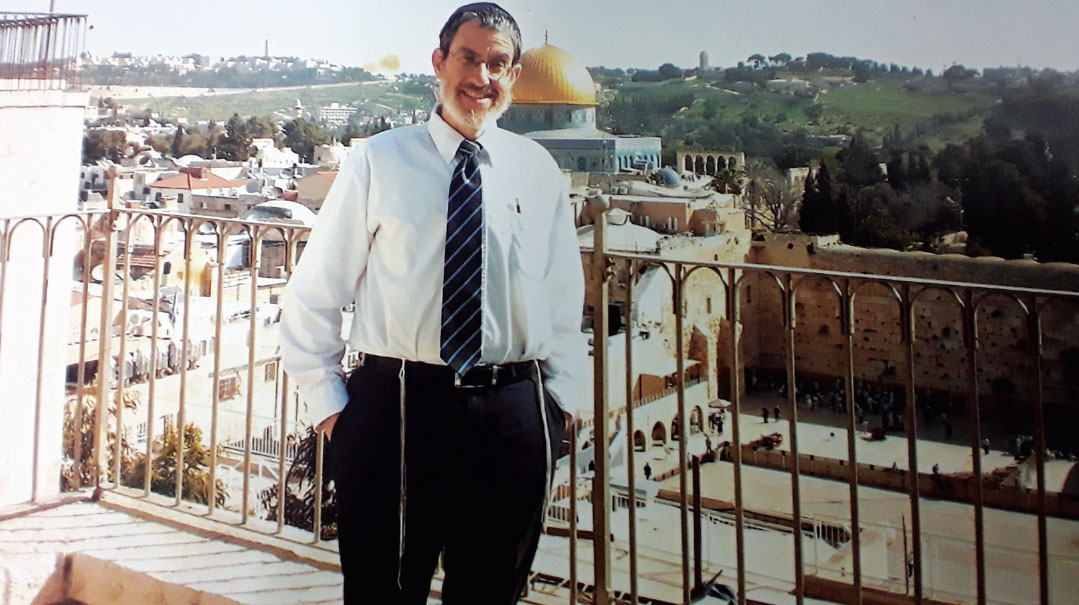

My beloved youngest brother, Rabbi Matisiyahu Rosenblum ztz”l

A round five months ago, I sat facing my brother Matisiyahu in his living room. I asked him whether he harbored any anger at anyone for the delay in diagnosing his cancer (one that included aggressive in its name) at the outset and the slowness with which the results of his first scan came back. He did not flinch before answering: “I believe in G-d. If that’s how it worked out, that’s how it was supposed to work out.”

Matisiyahu was a yarei Shamayim through and through. He used to joke that he was perhaps the first baal teshuvah in history to become religious from a fear of Gehinnom.

To that yiras Shamayim, he would add overwhelming ahavas Hashem. In an email to Rabbi Yisrael Shaw, the editor of his forthcoming sefer, six days before his passing, he wrote that “acknowledging G-d’s good should be a special focus for me in particular. The name Matisiyahu has the connotation of ‘G-d gives’ or ‘gifts of G-d.’ ”

He achieved that rare madreigah, described by Rav Wolbe in Alei Shor, of coming closer to Hashem, even as Hashem was taking his life. His oldest son, Avraham Yeshaya, heard him repeating Shema over and over, in a barely audible voice, in his final moments.

MATISIYAHU, or Matthew, as he was then known, was the youngest of five Rosenblum boys. At four years old, in the midst of a family discussion about college applications, he piped up, “Amherst, that’s the one you have to apply early decisions.” None of his older brothers were allowed to read comic books, lest we be distracted from our academic endeavors. But that concern did not apply to Matthew. My parents just worried that he should be normal.

But my father’s judgment toward the end of high school — “I always thought you were an unhappy kid, but I now see you are just different” — was on target. He always had a close group of friends, with whom he maintained contact his entire life.

Matthew followed three older brothers to Yale, where, as in high school, he quickly outshone them all. As a freshman at Yale, someone asked him before a final exam how many of the optional readings he had done. “All of them,” he said. Yes, in part, that reflected a desire for good grades: He never received anything but an A at Yale. But more importantly, it reflected his love of learning and knowledge.

By the time he arrived in Israel for a year off after college, he already had three religious married brothers living there. There was no sneaking up on him, and he was fully defended. He had not taken well to his next-oldest brother Max and sister-in-law Brandy kashering the Rosenblum home, which he considered an outside invasion.

But twice in his first week in Jerusalem’s Nachlaot neighborhood, his apartment was robbed, and he had little choice but to come live with my young family. At our Shabbos table, he met many students at Machon Shlomo, a local baal teshuvah yeshivah, then in its early years. Many would eventually become his closest lifetime friends.

When a student in the upper shiur at Machon Shlomo departed, leaving only three, Yitzchok Feldman, who had become friendly with Matisiyahu at Yale, prevailed upon Rabbi Beryl Gershenfeld to offer Matthew a spot. That offer, made in person on a Sunday morning, came at a propitious moment. It followed a screaming argument between Matthew and me on the preceding Thursday night about the direction of his life, after which we spent several hours walking around Har Nof in the early hours of the morning.

THE WORLD OF TORAH and yeshivos quickly proved Matisiyahu’s natural habitat, and, I’m confident, the only one in which he could have ever been fulfilled. In his final months, he told my youngest son, Elimelech, “My greatest joy in life is learning Torah. Every time I learn of a new aspect of Torah, I want to know it all.”

His first Gemara rebbi, Rabbi Shaul Miller ztz”l, one of Rav Abba Berman’s closest talmidim, had a rule that he never taught a sugya unless he had reviewed it 40 times. He quickly upped that number to 100 when Matisiyahu entered his shiur.

His friends at Yale had teased him that he was too much of a nerd to ever find a wife in the secular world, but that he could always join his brothers in yeshivah — a place that puts such a premium on intellectual firepower that surely a wife could be found.

But his attraction to the world of Torah had little to do with such practical considerations. He was as genuine a truth-seeker as I have ever met. He was never content with the level of understanding that his natural brilliance allowed him to access quickly. He always had to grasp the full picture, the deeper understanding. And when the pieces fit and the picture was complete, he reached a state best described as child-like wonder, fairly jumping up and down in excitement.

As a seeker of truth, he was mevatel himself in front of all those whom he felt could bring him to a deeper understanding. Rabbi Yitzchok Feldman, the rav for a quarter century at Emek Beracha in Palo Alto, wrote in his hesped, “Matisiyahu had already been the fastest intellect in most rooms he inhabited by the time we met [at Yale]. That was his calling card, and it gained him entry to many great Chachamim.... His rebbeim allowed him to trail them doggedly because they saw how much he wanted to learn, and how much he could do with it.”

The first of the seminal influences on him was Rabbi Beryl Gershenfeld at Machon Shlomo, and for years thereafter. At the shivah, I related to Rabbi Gershenfeld that one of my brother’s talmidim had written that he would have exploded from the pressure as a newcomer to Machon Yaakov, where my brother taught and mentored talmidim for 15 years, but for a yesod in Divine judgment that my brother shared with him. I asked Rabbi Gershenfeld if he knew the source of that yesod. He told me that it is found in the Hakdamos U’shearim of the Leshem, the great Lithuanian kabbalist, which he and Matisiyahu had learned together. Rabbi Gershenfeld then enumerated many other sifrei Kabbalah they had learned.

From Machon Shlomo, Matisiyahu went to Mercaz HaTorah for two years, and then learned in Rav Tzvi Kushelevsky’s Heichal HaTorah for more than a decade. “Every blade of grass has a malach that strikes it and tells it to grow,” Matisiyahu once said. “For me, Rav Tzvi Kushelevsky has the status of that malach.”

Rav Tzvi is an illui whose method in learning is based on hard work — meticulous, close reading of the words of the Rishonim. Matisiyahu would have been the first to acknowledge that his natural gifts were no match for Rav Kushelevsky’s, but the method suited him perfectly. He once told me that Rav Tzvi often starts at step three of the argument, because the first two are so intuitively obvious to him. He viewed his task in shiur as clarifying those first two steps.

Rav Tzvi loved Matisiyahu, and often discussed the shiur with him both before and after it was given. He usually (not always) enjoyed the way Matisiyahu’s critical and aggressive intelligence pushed him to ever further clarity. Once they were arguing after a shiur klali, and Rav Kushelevsky had to leave for the airport. Forty-five minutes later, the phone rang in the yeshivah. It was Rav Kushelevsky asking for Matisiyahu: He had another proof to his position from a Meiri.

Another of the great influences on Matisiyahu was Rav Aaron Lopiansky. In his second year at Machon Shlomo, Matisiyahu hired Rav Lopiansky to learn with him at the Mirrer Yeshivah. That relationship remained lifelong. Rav Lopiansky’s dialectical mindset and unique ability to see all the multifaceted aspects of any issue perfectly suited Matisiyahu’s perpetual quest for a larger synthesis. He once told me, “I know at the end of every 45-minute shiur of Rabbi Lopiansky, I will have a yesod that I can apply in my own life and avodas Hashem.”

Matisiyahu undertook the herculean task of listening to hundreds, if not thousands, of cassettes of Rav Lopiansky’s shiurim. (He once joked that a childhood endeavor of organizing 3,000 comic books, each in a laminated cover, had been good preparation.) He categorized and summarized them, and created a website. That website will be one of his enduring monuments. Rav Lopiansky told me during the shivah that Matisiyahu brought him to a level of harbatzas Torah that he could never have achieved without him.

The creation of the website reflected Matisiyahu’s need for order — one of his greatest strengths. After every shiur, he wrote down on a separate note card every yesod that he gained from the shiur. Boxes filled with those neatly filed note cards — decades of the shiurim of Rav Moshe Shapira ztz”l, more than a decade of Rav Tzvi Kushelevsky — go from floor to the ceiling in his basement.

He followed the same methodical approach in mastering the vast expanse of Torah. He once told his daughter that just as one cleans a messy room by picking up one item and then another and then another, he created obligations for himself to first complete Shas, then Tanach, and so on, with invariable daily quotas that he never missed until his final illness. After he and his wife sold their car, he rejoiced in creating daily sedorim for the bus ride from his Telshe Stone home to Har Nof, where he taught, and back — two sedorim each way.

THE LAST FIFTEEN YEARS of his life he served as mentor/shoel u’meishiv at Machon Yaakov, in addition to substituting for Rabbi Gershenfeld’s Chumash shiur on the latter’s frequent trips abroad. Rabbi Avraham Yaakov Jacobs, the founder of Machon Yaakov and a good friend of my brother’s from their days together in Machon Shlomo, made him Machon Yaakov’s first hire in 2005, though initially he expected his influence to be limited to two or three very bright students a year.

Providing Matisiyahu with the opportunity to share his Torah with others, Rabbi Jacobs has told me many times, will be his claim to Olam Haba. A plaque will soon mark the corner of the beis medrash where Matisiyahu held court and from which the energy of afternoon and night seder emanated.

Matisiyahu was not an obvious choice for the role of mentor in a baal teshuvah yeshivah. He was an introvert by nature, though he had a remarkable capacity for deep and lasting friendships, going back to his high school years. The number of people who called last week to say, “I loved Matisiyahu,” was extraordinary. “Every conversation with him was transformational,” remembered one friend. “He took you either upward or inward.”

He once told his only daughter, “I don’t grasp people intuitively.” But he did what he always did in such situations — purchased an extensive psychology library (largely in secondhand bookstores) and immersed himself in the subject. He took a course in narrative therapy as a means to draw out others in conversation. Listed on the Machon Yaakov schedule were “opportunities to walk with Rabbi Rosenblum.”

At the same time, he brought some rather unique traits to the task of mentoring, most obviously his sense of humor. Virtually every email received in the period up to his passing and afterward contains some form of the words “brilliant” and “hilarious” in close proximity. “Quirky” also made frequent appearances. The wife of one of his closest friends wrote last week that she always knew when her husband was speaking to Matisiyahu on the phone from his belly laughs.

When Matisiyahu first received his diagnosis, he told me — his older brother by almost 12 years — “I would have had such a great hesped for you, and now I may never have a chance to give it.” As the foregoing indicates, much of his humor was unfiltered. He once described Rosenblum minds as possessing “strong motors, but weak steering wheels,” primarily in reference to himself and me. But even the unfiltered comments were not without purpose.

“He had the power to the rip the Band-Aid off any subject in an instant,” said Rabbi Jacobs, a daily confidant for 16 years.

Most of his humor carried within in it real insights delivered in an easy-to-take package. With his humor he broke down the barriers between him and his students and made rabbis seem less austere and forbidding.

Then there was the breadth of his yedios haTorah. One former talmid, who has been learning full-time for the past 13 years, recalled Matisiyahu learning with him Nefesh HaChaim when he could barely read Hebrew. Last week, he offered a chavrusa to anyone who wants to learn Nefesh HaChaim, l’illui nishmas my brother. Another mentioned to me at the shivah house learning the introduction to Alei Shor with him.

One talmid was obviously brilliant, but some visual impairment made it almost impossible for him to read. My brother suggested that they speak out the Gemara “outside.” That talmid went on to learn for two years at the Mirrer Yeshivah, after Machon Yaakov, and thereafter to become a daily chavrusa of my brother’s via Skype and one of his closest friends.

For all his talents, he had almost no ego. Most of his humor was self-deprecatory. Students, chavrusas, and even those who just sat next to him at a Shabbos table were struck by his genuine interest in them and frequent expressions of delight in their insights.

No question or expression of religious doubt made him nervous. Because of his intellectual honesty, he had worked on almost every question himself on his religious journey. He was completely non-judgmental. That made him a safe space for the expression of questions, and, as a consequence, made it possible for him to provide answers.

One talmid, an Ivy League graduate, wrote of my brother recently:

He was probably the most honest man I have ever met. He had the power to meet a person exactly where he was, with complete acceptance. He was able to simply mirror back to me exactly where I was. Whatever question or internal dilemma or decision I was grappling with, he was always able to perfectly reflect back to me exactly where I was holding and what I was thinking. He helped me understand myself greatly. He could meet you — and you could meet yourself — safely with him. When he became more ill this summer, I was able to see more clearly how his radical acceptance of others stemmed from his deep and powerful emunah. He accepted everything and everyone without any judgment whatsoever.

A rebbi at Machon Yaakov told me during the shivah, “There are many young men who would not be committed observant Jews today if it were not for your brother.”

The same non-judgmental acceptance characterized his child rearing. He did not try to force his children to live out his dreams for them. He once told his beloved daughter in the middle of an intense discussion, “You don’t have to accept my opinion. You are a different person than I am. But we must treat each other’s opinions with respect.” As a consequence, each of his children shares his own yiras Shamayim, as was evident in the shivah house.

THE FINAL MONTHS of Matisiyahu’s life were painful ones, but also ones that brought with them a palpable sense of completion. Unable to learn most of the time, and often even to daven, he focused on expressing his hakaras hatov to all those who came to visit and to everyone in the hospital, from the medical staff to the floor cleaner, and on long talks with his wife Chana, who devoted herself to him in every way possible.

Joel Gedzelman, a chavrusa over decades, came to visit almost daily. Besides Matisiyahu’s expressions of wonderment that he had come again, what stood out for him was how Matisiyahu kept the focus on Joel and what was going on in his life.

For two weeks, after his wife was struck with the coronavirus, my wife and I and our youngest son were the only people allowed to visit. We frequently reviewed what a good life he had been blessed with — an example of what Rav Yechezkel Sarna once said in a eulogy: “He did not have a short life; he had a fast life.” Every moment filled. My only regret is that I did not know more of his impact on talmidim when we did those reviews. He never spoke of it, and was probably not aware of it until the emails poured in during his final illness.

Never far from Matisiyahu’s bed was the soon-to-be published Letters to Jordan, almost 400 pages of essays written in response to the questions of his students. The eponymous Jordan, in a letter written to my brother about six months ago, describes himself as having been a barely literate modern Orthodox kid who hated learning Gemara, when he first encountered my brother. Today, he is a musmach of Yeshiva University who has given an entire cycle of daf hayomi shiurim.

My brother would not let me close to the manuscript. He wanted it to be fully his. And we both knew that I never delved into his sources as he had. He could not bear the thought of a superficial version of ideas that were b’nafsho.

In his final weeks, my brother said frequently that he wanted nothing more than to be able to live as a Jew — to daven, to put on tefillin, to think in learning. His final Shabbos, the day before his passing, he was home in Telshe Stone at the Shabbos table, together with Chana, surrounded by their five children, four married, and their eight grandchildren, four born in the last eleven months. For the first time in a long time, he was able to hear Kiddush and hamotzi and eat of the challah. On Motzaei Shabbos, when my wife and I came to visit, he was completely at peace.

I HOPE MY READERS will forgive me if I conclude with a few words about our relationship. He once heard someone with whom he was close speaking derogatorily about me. He told that person, “You are a lamdan. Anyone can see my brother’s faults. But why don’t you be a lamdan and uncover his maalos.” He was that lamdan for me. He knew everything about me that could use improvement, and sometimes even noted them. But as a consequence, a compliment from him was priceless.

He was my sharpest critic and the fiercest booster of my books. Many times he tried to send me home from the hospital, on the grounds that he was sick of hearing about the “only one more chapter” I still had to write in the biography of Rabbi Meir Schuster ztz”l. When he told me recently, “You found your tafkid,” nothing could have made me happier.

Last week, as he returned to Telshe Stone after months in the hospital, he met an avreich from his morning kollel. The avreich asked him, “Mi doeg alecha — Who is worrying about you?”

He responded, “I have a big brother who worries about me and loves me very much.” Baruch Hashem, he knew.

May he be a meilitz yosher for his wife Chana, his children and their spouses, and his grandchildren, and for our mother, may she live and be well. —

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 836. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com

Oops! We could not locate your form.