A Shlichus Like No Other

| July 8, 2025This forced sojourn in a foreign land could have been a footnote in Rav Avraham Chaim Naeh's. Instead, it became a defining chapter

Title: A Shlichus Like No Other

Location: Alexandria, Egypt

Document: Sefer Shenos Chayim

Time: 1915

AS war clouds gathered over Europe in 1914, the Ottoman Empire, having cast its lot with Germany, began to view the Jewish population of Palestine with increasing suspicion. Authorities issued a harsh decree: all residents with foreign citizenship could either become Ottoman subjects — which for young men meant almost certain conscription into the sultan’s army — or face immediate expulsion from the empire.

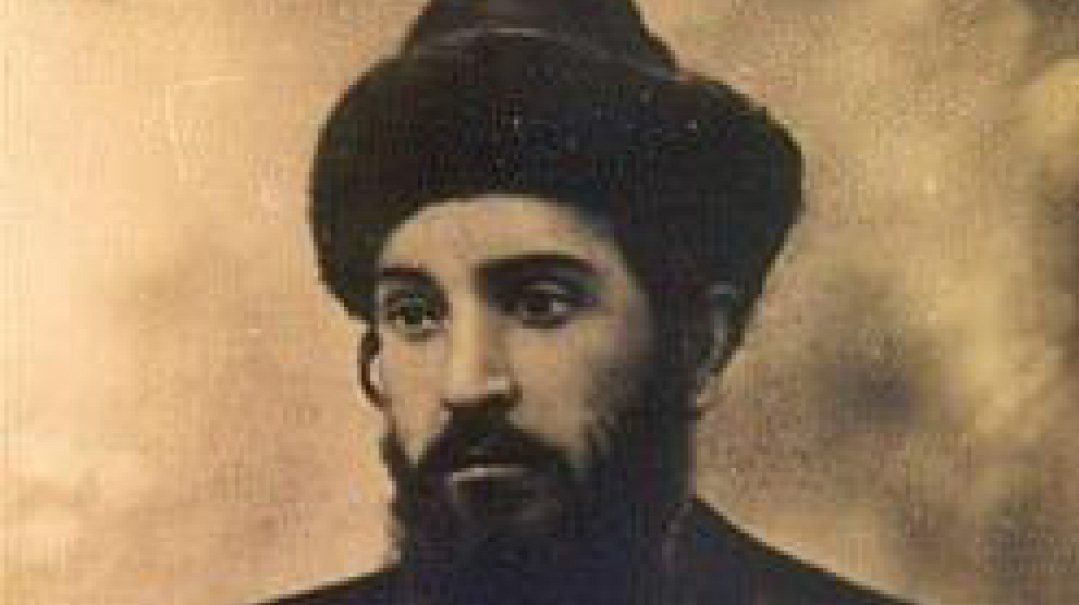

For thousands of Jews, many of whom held Russian passports and were now deemed enemy aliens, there was no choice at all. Among them was a brilliant 24-year-old scholar of distinguished lineage from the holy city of Chevron, Rav Avraham Chaim Naeh. He joined a stream of refugees onto ships that carried them across the Mediterranean to the ancient cosmopolitan port of Alexandria, Egypt.

For Rav Naeh, this forced sojourn in a foreign land could have been a footnote in a life already marked by extraordinary scholarship. Instead, it became a defining chapter. The lessons he learned on the banks of the Nile from his fellow exiles from Palestine, as well as from the established Sephardic community of Alexandria, would set the stage for the monumental works and communal leadership that defined his legacy.

R

av Avraham Chaim was born in 1890 in the old yishuv of Chevron into a veritable rabbinic aristocracy. His father, Rav Menachem Mendel Naeh, was a distinguished Chabad chassid and served as rosh yeshivah of the Magen Avos Yeshivah in Chevron. This yeshivah had been founded by Rav Chaim Chizkiyahu Medini, the author of the encyclopedic Sdei Chemed, who served as the city’s chief rabbi. Rav Avraham Chaim’s mother, Mussia, was the daughter of Rav Berel Ashkenazi of Kalisk, who had served as a shadar (emissary) and chozer for the third Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Tzemach Tzedek.

As a child, he was a fixture in the beis medrash of the Sdei Chemed, absorbing top-tier Torah scholarship. Anecdotes from this period relate that townspeople would often approach the young boy with halachic queries, and to their astonishment, he would provide clear and well-reasoned answers, demonstrating a precocious command of complex sources. The Sdei Chemed himself took a special interest in the gifted child, granting him personal access to his vast library to prepare his bar mitzvah derashah.

After young Avraham Chaim’s family relocated to Yerushalayim, he continued his studies at the famed Yeshivas Ohel Moshe, under Rav Yitzchak Yerucham Diskin. In 1911, at the tender age of 21, he was handpicked by the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe Rashab, for a mission of immense responsibility. He was dispatched to the remote city of Samarkand in Bukhara (modern-day Uzbekistan) to provide much-need rabbinic leadership to the ancient Jewish communities there.

In this foreign environment, he displayed the resourcefulness and dedication that would characterize his entire life. He quickly taught himself the local Judeo-Bukharian dialect and authored a sefer addressing the unique needs of the community’s youth. This early mission, long before his exile to Egypt, established his identity as a practical, hands-on builder of Torah who could adapt his formidable knowledge to serve the needs of any Jewish community, no matter how distant or different.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 shattered the relative tranquility of the Yishuv in Palestine. The Ottoman rulers, now allied with Germany and at war with Russia, began to implement harsh policies against foreign nationals. On December 17, 1914, later remembered as “Black Thursday,” the authorities began a mass deportation of Jews from Jaffa who held Russian or other enemy-nation citizenship. Over the next few months, a total of 11,277 Jewish men, women, and children were forced onto ships bound for uncertain destinations. Young Rav Avraham Chaim Naeh was caught in this dragnet and compelled to leave his homeland. The tides of war carried him and his fellow exiles to Egypt, to the bustling, ancient city of Alexandria.

The Alexandria that greeted the refugees was a world away from the cloistered piety of Chevron and Yerushalayim. It was a vibrant, multicultural metropolis, a major commercial and cultural hub of the Mediterranean. Its own Jewish community was large, prosperous, and diverse, having swelled from just under 10,000 members in 1897 to nearly 25,000 by 1917. This community was a heterogeneous mix of Sephardic Jews from Ottoman lands and European Jews who had settled there for business, creating a dynamic society. This established community was suddenly overwhelmed with thousands of penniless refugees from Palestine, creating an immediate and desperate need for spiritual and physical infrastructure.

In this chaotic environment, Rav Avraham Chaim founded an advanced Torah institute to serve the exiled students. The name he chose for this institution was both poignant and powerful: Yeshivas Eretz Yisrael. It became a spiritual home and an anchor for over 200 young men, providing them with the continuity and stability that had been stolen from them. Among its students was a young man named Asher Zelig Margolies, who would later become a renowned kabbalist in Yerushalayim.

R

av Naeh’s activities in Alexandria were not confined to the walls of his yeshivah. Displaying the same pragmatic sensitivity he had shown in Bukhara, he recognized that the local Egyptian Jewish community, as well as the many Sephardic refugees, had their own unique customs and required a halachic guide tailored to their needs. During his years in exile, he authored Shenos Chayim, a concise digest of Jewish law based on the rulings of the Arizal, the Beis Yosef, and the Chida, specifically following the customs of Sephardic Jewry. This work, essentially a Kitzur Shulchan Aruch for the Sephardic world, was published in Egypt around 1915.

This pattern of identifying a specific audience and creating a tailored Torah work for them would be repeated throughout his life, most notably in his later masterpiece, Ketzos Hashulchan, which aimed to make the rulings of the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch Harav accessible to a wider audience.

In 1918, Rav Naeh returned to Eretz Yisrael and settled in Yerushalayim, where he was appointed to the pivotal position of personal secretary to Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld of the Eidah Hachareidis. In 1948, with the establishment of the State of Israel, he became a founding member of the Vaad Harabbanim of Agudas Yisrael. He was also instrumental in founding the newspapers Kol Yisrael and Hamodia. At the same time he served as rabbi of the Bucharian neighborhood of Yerushalayim and was intensely focused on publishing his many Torah works.

A simple, poignant story related by his daughter, Mrs. Chana Kozlovsky, offers a powerful glimpse into his true character. She recalled asking her father why he toiled over his voluminous writings late into the night, rather than during the day. He replied simply, “If I wrote during the day when the kids are around, I’d have to tell them to stop playing. I didn’t want to do that, so I write at night.”

Rav Avraham Chaim Naeh passed away in 1954 at the age of 64, and was buried on Har Hamenuchos.

Is an Olive Really an Olive?

While his leadership left an indelible mark, Rav Naeh’s most enduring legacy is undoubtedly his monumental work on shiurim — the precise measurements required for the fulfillment of countless mitzvos. His magnum opus, Shiurei Torah, first published in 1947, was a work of breathtaking scholarship and immense practical significance.

For centuries, the exact modern equivalents of Talmudic measures like the k’zayis, reviis, and amah had been the subject of uncertainty. Rav Naeh undertook the colossal task of converting these ancient quantities into clear, contemporary metric units like cubic centimeters (cc). This was no mere academic pursuit; the ability to perform a vast range of halachos — from eating matzah on Pesach to the dimensions of a succah — depended on these precise figures.

His methodology was rigorous. He based much of his research on the rulings of the Rambam and on a brilliant insight: the weight of the Ottoman dirham had remained remarkably stable for centuries. He employed it as a reliable bridge between medieval measurements and modern ones.

This groundbreaking work placed Rav Naeh in a celebrated halachic debate with another of the generation’s titans, Rav Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, the Chazon Ish. The Chazon Ish, through his own independent analysis, concluded that the ancient shiurim were significantly larger than Rav Naeh’s calculations.

What made this profound disagreement legendary was the atmosphere of immense and unwavering mutual respect in which it was conducted. It is recounted that after their meetings to discuss these matters, the Chazon Ish would personally escort Rav Naeh all the way out of his home to the street — a gesture of extraordinary respect reserved for the most distinguished of guests.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1069)

Oops! We could not locate your form.