Niggun for Broken Hearts

What really sparked my curiosity was the tune he used to accompany his Torah learning. Little did I know it would change my life. A true story

I

t was an exciting time in my life. It was right before Shavuos, and I was about to celebrate my marriage, plus the publication of my first sefer, which I was working on in honor of my upcoming wedding. It was called Megillas Shir, an acronym for my own initials and those of my wife, and copies would be given to the wedding guests as a memento.

I wouldn’t have mentioned the book among the most important events of my life then, except for the fact that it wound up being a catalyst for change in a profound way. And perhaps it will cast the Yom Tov of Shavuos — and maybe even life in general — in a different light for you as well.

Most of my work on the sefer took place in the afternoons in a small shul near my yeshivah, where there was an unspoken secret: A remarkable man named Reb Yisrael spent his days upstairs in that quiet shul, devoting his life to Torah and avodas Hashem. He had a large family, but only returned home for Shabbos. The rest of his week was devoted to his intensive regimen of Torah study.

People would stand in line to receive brachos from Reb Yisrael; others vied for the zechus to give him some financial support, hoping to gain even a tiny share of the merit of his spiritual accomplishments. But Reb Yisrael, with his warm, delicate smile, invariably turned them down. He never prided himself on his accomplishments or considered himself worthy of anyone’s support. His sole partner in life was his wife, a woman as remarkable as Reb Yisrael himself, who dedicated her own life to supporting her saintly husband, as well as being a powerhouse of chesed in her own right.

During that period, there were many times when I found myself alone in the beis medrash. Yet even after the Minchah-Maariv crowd dispersed, the sound from the ezras nashim above my head lingered on. It was the soft, incomparably sweet voice of Reb Yisrael. I soon discovered that the venerated masmid was also blessed with a gifted voice. As darkness descended on the Holy City and silence filled the air in the beis medrash, it was as if the song of the angels themselves were emanating from the women’s gallery upstairs.

In time, I learned how to identify subtle differences in his tone. It was always the same haunting niggun, but with slight variations depending on whether he was trying to resolve a difficult question, or whether he was reviewing a Rashi. Sometime that niggun took on a nuance of intense yearning. And then, when he succeeded in clarifying all of the details of a sugya and all of his questions had been resolved, the entire beis medrash echoed with a song of joy so elevated that it obviously surpassed any other form of human happiness. He sounded as triumphant as a military commander whose battalion had emerged victorious from a seemingly hopeless battle.

I knew about him and I assumed he knew about me, but we never directly communicated with each other — because I never had the courage to climb the stairs to the second floor and interrupt the Torah study that seemed to hold up the world.

Meanwhile, my sefer had taken shape and had already been sent to the printer, when I felt a pang of regret: Why hadn’t I consulted with Reb Yisrael beforehand, perhaps asking him to review the manuscript or at the least, offer some profound insights? I’d been sitting a few feet away from this venerated talmid chacham for weeks — how did I not have the courage to take the opportunity?

With newfound resolve, I decided I couldn’t just let it go. Even if the things I learned from him wouldn’t be included in the sefer, I could still absorb a wealth of Torah knowledge from my fellow occupant of the shul. Even more importantly, I could solicit a blessing in advance of my marriage.

During the week, it was impossible to interrupt him. Part of the reason was technical — the ezras nashim was locked — but even more than that, no one dared disturb this living sefer Torah in the middle of his learning. I decided to wait until Friday night to approach him and introduce myself.

Even then, it wasn’t simple. After davening, I wasn’t the only one waiting to speak to him. Reb Yisrael was engaged in conversations with many other residents of the neighborhood. Some had complex questions about various sugyos in Shas; others wanted to discuss personal issues, and still others were there simply to wish him a good Shabbos and to receive his blessing in return.

Reb Yisrael finally turned to leave, accompanied by his eight sons, along with several people from the neighborhood who lived alone and regularly ate their Shabbos meals at his table. I quickly moved to intercept him. Holding out an uncertain hand, I wished him a good Shabbos.

With a broad, congenial smile, Reb Yisrael returned the handshake and replied, “Good Shabbos and a gut yohr to you.”

Before I could utter another word, he said, “How are you? Perhaps you can do a tremendous favor for me, for which I will owe you a debt of gratitude for the rest of my life?”

I understood that this was the preamble to an invitation to his home, and I quickly explained that I planned to have the seudah in my yeshivah, where my friends were waiting to celebrate our last Shabbos together. I asked if I could save the invitation for a different time, together with my wife.

“I don’t know if the Rav knows me,” I continued. “My name is Shimon Breitkopf. Over the past two months, I’ve been writing a little bit about Megillas Rus, and I wanted to ask the Rav to review what I have written.”

Reb Yisrael nodded approvingly. “Megillas Rus is very important,” he said. “There are few peirushim on it, so you’ve done a good thing. Kol hakavod. I have a few rare seforim on Rus, but I gather it’s too late for that.”

“Yes, it’s already gone to print,” I admitted.

“Don’t worry. Perhaps my seforim will help you for future editions,” he said. “But I’m curious — what was your answer to the basic question of why we read Megillas Rus on Shavuos?”

I shared all of the explanations I could remember. Reb Yisrael made a point of expressing delight over every answer, as if he hadn’t already known all of them. When I was finished, he said, “Listen, Shimon, come to me on Sunday at four o’clock. I want to share another answer with you, one that you didn’t write. It won’t be included in your sefer, but you’re about to begin building your own family, and I think it will be very helpful to you.”

I couldn’t believe my good fortune. The ezras nashim was like a closed military zone — I’d never seen a soul venture inside. Yet here I was, invited to join him in his sanctum. It was like a miracle had taken place.

I arrived at the shul and climbed the steps, feeling both eager and nervous. Reb Yisrael escorted me to his table, which was laden with books and handwritten chiddushim, and motioned for me to sit down across from him. There was a stack of seforim right in front of him, but Reb Yisrael looked over them right into my eyes — I felt that his gaze was boring into my very soul. What, exactly did he want from me? For a full two minutes, he gazed at me intently, while his hands moved quickly back and forth behind the pile of books. After those two minutes were up, he produced a large pad of paper, and I was astonished to discover a remarkably accurate sketch of my own face, which he had somehow produced while I sat across from him.

I didn’t get it. Why would the saintly Reb Yisrael use his precious time to draw pictures of other people? As if that weren’t strange enough, he proceeded to ask me, “Nu, Shimon, what do you say about this picture?”

I really didn’t know what to say. “Uh… I don’t exactly know very much about these things, but… it’s very interesting. It’s… very special.” I squirmed awkwardly in my chair, but Reb Yisrael just kept smiling.

“I’ve seen you here over the last few months, and I promised you a peirush on Megillas Rus,” he said, and indicated the picture he had drawn. “This is part of the peirush.”

At that point, all I could think about was how to extricate myself from this bizarre situation. What had happened to the rav whom I had admired so deeply? After a minute of silence, Reb Yisrael began explaining, beginning with a lengthy personal story. It was a shiur that transformed my Shavuos, and my entire life since.

What follows is the story he told, in his own words.

***

My connection to Megillas Rus began at my birth on Shavuos night. I was named Yisrael — both for Am Yisrael, and for the Baal Shem Tov, who passed away on this holy day. My father, a tremendous and well-known talmid chacham, decided to add Dovid to my name, as a reference to Dovid Hamelech, who was born and passed away on Shavuos. But my family called me “Luli.”

I was my parents’ only son, born after six girls, and as you can imagine, I became their little star. My sisters danced around me all day long and set up a rotation for the privilege of taking care of me. And while the female side of the family did everything to make sure my physical needs were met, my father was focused on my spiritual development. When we began learning Chumash Bereishis in cheder, my father taught me all the midrashim. My father taught me how to learn Gemara at a very young age, and my mother’s greatest joy was when we learned in the house. She would sit in the kitchen and kvell.

From my sisters, who were all much older than me, I learned to draw and play music. My oldest sister was a talented artist, and I’d sit and watch her produce her masterpieces, while my second sister taught me to play guitar.

The discussions about my bar mitzvah began on my 12th birthday. Every meal turned into a planning session and there were many issues to be discussed: Should the bar mitzvah be celebrated on Shavuos itself? Who should be invited, and where should the guests be housed? Ultimately, it was decided that a Yom Tov meal for our close family would be held on Shavuos night, and a larger bar mitzvah reception would be held in a simchah hall after the holiday.

There was one thing that was never a question, though: Obviously, I would lein the entire Torah reading for Shavuos, including Megillas Rus. All of that, however, was merely the prelude to a much more important question: What would be the topic of my bar mitzvah drashah? Different subjects were discussed, and then my mother finally came up with an idea none of us could refuse.

“Do you remember, Meir?” she said to my father. “The night that Luli was born, you went to the yeshivah to learn. I wasn’t due to give birth for another two weeks, and neither of us thought that it would happen on Yom Tov.”

“I remember,” my father confirmed. This was probably the thousandth time he was hearing the story about the unexpected and complicated birth my mother endured alone.

“What were you learning that night?” she asked. “Let Luli speak about that sugya at his bar mitzvah.”

My father stroked his beard. “What was I learning that night? That is an excellent question. It was the summer when we learned Nedarim… On the night of Shavuos, we were learning daf kaf ches, the sugya of Bar Peda.”

“Excellent!” my mother exclaimed. “Let Luli speak about that!”

My father wasn’t as excited by the idea. “It’s a very complicated sugya,” he said. “It isn’t a good topic for a 13-year-old boy, and I doubt the guests will be interested either.”

But my mother was adamant. She had made up her mind, and as far as she was concerned, the subject was closed. “Learn the sugya with Luli until he knows it backward and forward,” she said. “I’m sure he’ll come up with a chiddush to say.”

Truth be told, my father was right, but under his instruction — accompanied by a huge dose of effusive praise — I was able to tackle it. We learned for two hours each day, the entire house taken over by Bar Peda. All of my sisters could recite the distinction between kedushas guf and kedushas damim by heart; my mother would mumble the Ran’s explanation of the sugya in her sleep. During the course of our learning, I wrote down several of the questions and answers that came up over the course of our study — and that’s how I had a beautiful drashah to deliver, just as my mother had wanted.

I’m really just telling you this as an introduction to a custom that began the year of my bar mitzvah and became a Shavuos night ritual. Every year thereafter, my father and I would forgo the beis medrash and instead spend the night learning the sugya of Bar Peda together at home. My mother would stay awake, too, serving us coffee and cake every half hour and beaming with pride. If my father and I hinted that we preferred to learn in an active beis medrash rather than at home, my mother wouldn’t hear of it. “Once a year, I need this,” she would say, and we were happy to fulfill her request.

My path in life seemed to have been defined for me in advance. The nearly three years I’d spent in yeshivah ketanah were a time of extraordinary growth. I learned well, I was scrupulous about observing every halachah, and I was a good friend to my peers and a loving son to my parents. In short, I was every parent’s dream.

During my free time at home and between sedorim, I enjoyed practicing the skills I’d learned from my sisters. At home I’d play my sister’s guitar, and I kept up the drawing, too. I had a secret notebook filled with sketches of people I knew. I kept that notebook hidden, though, because although there was nothing wrong with this little hobby of mine, I didn’t think it was appropriate for a yeshivah bochur to be involved in such things. I was also afraid that if the notebook were discovered, the people I drew might be offended. And so I kept that notebook locked away in my closet in yeshivah, taking it out occasionally late at night in order to relax.

The yeshivah where I learned had an excellent faculty, with one exception. There was one staff member with a very influential position among the bochurim who disliked me from the start. He considered me conceited, and he commented on several occasions that he felt I needed to learn humility.

During my years in that yeshivah, even though I had done nothing wrong, he regularly made a point of picking on me. From time to time he would subject me to withering criticism that pierced my self-esteem, but I just moved on and didn’t put up a fight.

Because I was one of the top students, he couldn’t find too many reasons to criticize me — but if he did, he wouldn’t miss the opportunity. When I davened a long tefillah, he chided me for trying to “make an impression on others at Hashem’s expense.” When I davened normally, he told me I needed to work on my yiras Shamayim.

I heard rumors that he had a son about my age who was no longer Torah-observant, and I told myself that this faculty member was taking out his frustration on me, and I hoped that his painful jabs at me would atone for my sins.

And this is where the real story begins.

It was the night of my 17th birthday, and as was our minhag, I spent Shavuos night together with my father, delving into the sugya of Bar Peda, with my mother hovering in the background.

In the morning, when I arrived at yeshivah, the rebbi who’d declared himself my enemy was waiting for me. “I see that you were not aware that we have a seder on Shavuos night in yeshivah,” he said tartly.

I knew that he was looking for a pretext to needle me. He knew very well that I never missed seder in yeshivah, and he also knew from previous years that I learned with my father at home on Shavuos night. I tried to remind him of that, but his mind was already made up. “Did you ask anyone for permission?” he demanded. “Do you think that there are no rules here? That this place is hefker?”

I’m not naturally impudent, but at that point I felt the harassment had gone too far. “The Rav is right; I have sinned,” I said. “Give me a punishment, and let us be done with this.”

He grew enraged by my chutzpah. Behind my back, he hissed, “You’ll hear from me yet!”

The next morning there was a major commotion in the courtyard. The yeshivah administration had decided to inspect all of the students’ closets and confiscate every questionable or forbidden item. Many of the bochurim were trembling in fear, trying to come up with excuses that would save them from the administration’s wrath.

For my part, I wasn’t concerned. There was no contraband of any sort in my closet. At least, that was what I thought… but then I remembered my notebook with the sketches. Woe to me if anyone found that notebook! I raced to my room, opened my closet, and rummaged through all of my books and papers. Everything was there… except the notebook.

I was suddenly gripped with terror. If the other bochurim found out about that notebook, it would be a disaster. I would be lost.

I began trying to come up with excuses of my own. Perhaps I could say that it belonged to my sister, or to a friend who wasn’t in the yeshivah… I davened Shacharis with extraordinary kavanah, and then I finally began to calm down. After all, I hadn’t done anything wrong. In the worst-case scenario, it would be slightly unpleasant for me that the faculty knew that the top student in the yeshivah had a secret hobby of drawing pictures during his spare time. It wouldn’t be pleasant, but it couldn’t be all that horrible.

In my blackest dreams, I could never imagine what was about to happen next.

That afternoon, a notice was posted announcing that an “important shmuess” would be delivered to the entire yeshivah right after Minchah. All of the students were expected to be present. As it was, everyone sensed that they needed an extra dose of Heavenly mercy.

The shmuess was delivered by the rebbi who had made me into his enemy.

“Rabbosai,” he began, “you know that we’ve gone through everyone’s closet, and I must say that we were shocked. The entire faculty was absolutely thunderstruck. We must give some thought to how we will rectify what is happening here.

“I will give you one example,” he continued. “This may well be the most appalling of all the things we discovered. There is a bochur here who thinks that he is a ben aliyah, who thinks that he is an excellent student. Now, this bochur considers himself a lamdan. And as a lamdan, he reasoned that there is a mitzvah to emulate the ways of Hashem. Therefore, he told himself, if Hashem is the ultimate Artist, then he can be an artist too! If Hashem creates images, then he can create images of his own. And so he sat and frittered away his time. If I hadn’t seen it, I would never have believed that even the least serious bochur in yeshivah could engage in such frivolous behavior and spend his time producing such foolish pictures. I won’t mention names, because that is not the point. But it is clear that there is something rotten here. It is clear that this is a bochur who is impudent and arrogant, and therefore his Torah is worth nothing. So it’s no wonder that he saw no reason to be here on the night of Shavuos. He has no connection to Matan Torah; he has no understanding of what it means to receive the Torah. Perhaps he has a future as an artist in America, among the goyim. But in the Torah world, there is certainly nothing for him to look for.”

I didn’t hear the rest of the shmuess. My head began to spin and my body went numb. I felt like I’d just been murdered. I sat in utter shock, while I saw my entire life collapsing before me like a house of cards. I must have blacked out for a few minutes, because next thing I knew, it was 4:15 and the shmuess was over.

I retrieved my hat and jacket and walked out of the yeshivah, my entire body trembling, as I made my way home. I was humiliated, frightened, and shocked. I felt as if I had been broken into a million pieces. I was completely crushed. When I arrived home, I climbed into bed, buried my face in my pillow, and burst into tears.

“Luli!” my mother exclaimed. “My Luli! What happened?”

But I couldn’t answer her. I could only sob heavily, wishing I would die. In fact, I wanted more than that — I wanted to vanish into thin air, as if I had never existed.

My mother called my father home, and after watching me writhing in wordless anguish, he called the rosh yeshivah to find out what had happened. The rosh yeshivah said he wasn’t there that afternoon, but he would try to find out. Indeed, he called back a few minutes later with reassuring news. “Everything is fine,” he told my father. “One of the rebbeim delivered a mussar shmuess, and your son probably took it a bit too hard. Everything is all right, Reb Meir. It will pass, you’ll see.”

But in reality, nothing was all right. I cried for two hours, while my mother was holding vigil by my bed.

“Would you like to drink, Luli? Should I bring you a wet compress?” But I just stared vacantly into space.

“Meir,” my mother finally said to my father, “run over to Luli’s yeshivah to find out exactly what happened. I don’t think we’ve heard the complete story.”

My father didn’t waste a second. He ran to the yeshivah, and when he returned home an hour later, he was in a fit of rage. I’d never seen him in such a state. My father, who embodied refinement and gentility, was red-faced with anger and in tears.

“Murderer! Murderer!” he shouted. “He will spend an eternity in Gehinnom! How could he do such a thing?! I thought I was sending him to a yeshivah, not a slaughterhouse!”

My mother looked at him in alarm, and they went out of the room. I heard my father tell her the horrific story, as he’d heard it from my friends — how this influential rebbi stood in front of 150 bochurim and spilled innocent blood, driving a knife into the heart of his beloved only son.

The rebbi tried to justify his actions. He told my father that he hadn’t mentioned my name and that he had been certain no one would know who he was talking about. If he had caused any damage, he added, then he was willing to come and apologize. But for me, it was already too late. I was completely shattered, broken into a million tiny shards.

I was ashamed to leave my house or see my friends. I sat in my room from morning until night, drawing and playing my sister’s guitar. I’d been a bochur filled with hopes and ambitions, instantly transformed into a broken vessel, a child whose future had been destroyed before it could even start.

A month went by, and then another. I couldn’t open a Gemara. I couldn’t set foot in a beis medrash. As far as I was concerned, it was all over. And so it was that I — Luli, the boy who was my parents’ greatest hope and the light of their lives, the pride of the entire family — found myself driven out of the world of yeshivos even before I had reached yeshivah gedolah.

Shimon, you don’t need to hear all the gory details — how I stayed in the homes of relatives who tried to rehabilitate me, but only caused me more suffering; how I was sent to various institutions that were not suitable for me; how I felt that I was being suffocated by overtures of love to the point that I looked for a way to cut myself off completely and become independent.

I made a few new friends and we rented an apartment together in Tel Aviv. I had no family, no Torah, no davening, and no emunah. All I had was one great mass of pain. But I had to find some way to support myself, so I spent my days sitting on the Tel Aviv boardwalk, letting my hair grow wild, offering to entertain passersby with my talents. At my side sat the guitar I had received as a gift from my sister, a black pencil, and a large drawing pad. I charged ten shekels for every picture I drew. As for the music, it was up to the passersby to decide. I didn’t really think being a street musician and artist was the most honorable profession, but I’d made peace with the reality of my life.

There are many bochurim who go off the derech and harbor profound resentment toward their families. For me, it was just the opposite. The truth is that I wasn’t angry with them at all — I loved them very much and I even pitied them. I knew I was causing them tremendous suffering, and I knew they weren’t at fault. That’s why I tried to stay as far away as possible. If I was out of sight, I thought I would be out of their minds as well. I didn’t visit them, and I rarely called. I hoped with all my heart they would simply forget about me — it would be better for all of us that way.

I called home twice a year, once on Erev Rosh Hashanah to wish them a good year, and also one other time — before my birthday on Shavuos. Speaking with my father was always awkward. Despite his good intentions, he had no idea what to ask or how to relate to a son who was not involved in learning.

“How are you doing? What have you been mechadesh?” he would ask innocently. But our conversation quickly petered out.

Only my mother would really speak to me. “Luli, how are you doing? Are you managing? Do you need us to send you anything? Would you like to come visit? We would like to see you a bit. Why don’t you come see your new nephews?” But I always politely refused. I didn’t want to cause them pain. At the end of every conversation, my mother would always say, “Luli, I was prepared to give up my own life in order for you to come into the world. And I will never give up on you.”

I would thank her, yet in my heart I wished my mother would indeed give up on me and allow me to have some peace of mind.

This situation continued for four long years.

***

One spring day, I was sitting on the boardwalk as usual, playing the guitar and waiting for some tourist to buy a sketch of himself, when suddenly I looked up and saw a man standing in front of me.

He was actually someone pretty well known among certain segments of the population, although I’d prefer not to mention his name. Besides, I — who had grown up in a sheltered world and had made the transition directly into a spiritual wasteland — didn’t know who he was. All I knew was that he was a Jew with long hair like me and was toting a guitar much like my own. The only difference was that pinned to that mane of hair was a kippah.

You know, when you’re used to drawing faces, you get used to looking into people’s eyes. And if you have enough experience, you can see everything there. I looked into the man’s eyes, but was caught off guard when I noticed that he was also peering into my eyes. We looked at each other for a moment and our gazes locked. To tell you the truth, I had never seen such eyes before, with so much light and love for his fellow man.

“How are you?” he asked, and with that greeting, I felt we’d been friends for years.

I was so flustered that instead of answering, I simply said, “Would you like a sketch?”

“Maybe I will take a sketch,” he said. “But to tell you the truth, the artist interests me more than the picture.”

He sat down beside me and placed his guitar on top of mine. Then he asked me gently, “My friend, can I ask your name?”

“Why not?” I replied. “My name is Luli.” But then I added, “Actually, my real name is Yisrael Dovid, because I was born on Shavuos. I was named for the Baal Shem Tov and Dovid Hamelech.” Suddenly I felt awkward. “Look,” I said, “I’m just a street artist and I play a little guitar. I have nothing special to tell you.’

But he seemed to know better, and didn’t give up so easily. “It may not seem very special to you,” he told me, “but to me, whatever you tell me will be amazing.”

At that point, something snapped — all the defensive walls I’d so carefully constructed came tumbling down. Soon I found myself telling my newfound friend the story of my life, from beginning to end. I told him everything — about my childhood, about my bar mitzvah, about my drashah on the sugya of Bar Peda, and about that dreadful day when my entire life changed in an instant. When I told him about the shmuess in the yeshivah, I noticed his eyes tearing up. But he continued listening quietly until I had finished talking.

When I finally finished, he sat in a profound silence for several minutes.

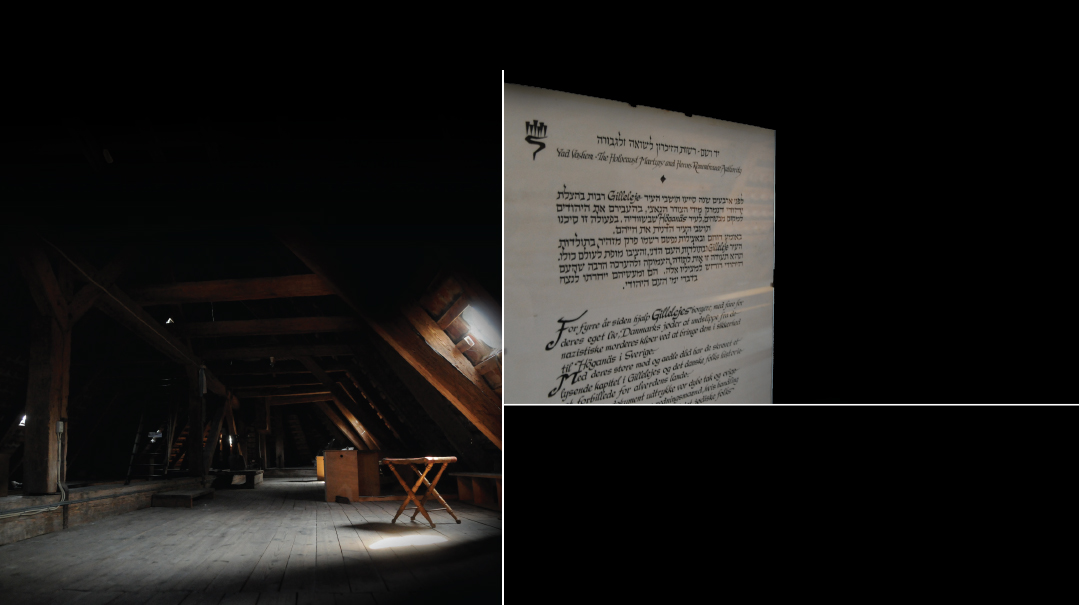

Finally, he said, “You should know that your pain reaches the throne of Hashem Himself. Listen, you’re a deep, sensitive young man, so you’ll be able to understand this: You know that on Shavuos we read Megillas Rus. There are many reasons for that. But I want to share a new idea with you.

“You see, there are two different types of Jews — ‘Matan Torah Jews’ and ‘Megillas Rus Jews.’ You know, a Matan Torah Jew lives on a very high level. He is a Jew who learns Torah day and night, who is attached to Hashem with all his heart. But in spite of all his greatness, he still can’t bring Mashiach.

“Mashiach will come from a Megillas Rus Jew. Mashiach comes from Rus, because Rus taught the entire Jewish People that the greatest achievements come after a person has been pushed away, after he has been asked to leave. She taught us that if you come back after you’ve been driven away, after you’ve been shamed, and you still cling to the Torah, then your Torah will become the Torah of Mashiach.

“Your name is Dovid,” he went on. “Dovid Hamelech also contended with shame and rejection. From the time he was born, he was denigrated and humiliated. But that made him a vessel for the most profound devotion that ever existed. You know, we all think that Shavuos is the holiday of the Jews who have a connection to Matan Torah, but I will tell you that it’s really a Yom Tov for the Jews of Megillas Rus.

“I walk around and I see so many children who have been rejected, so many lost souls, who don’t know how to turn around that rejection and become Megillas Rus Jews. You know, Luli, sometimes I think about Mashiach, sitting at the gates of Rome and waiting to come. But every day, he is rejected again. Not a day goes by when he isn’t told to wait. Mashiach has been hearing this for thousands of years already, but he hasn’t given up. He’s still sitting in the gates and waiting to be called.

“You should know that when a person comes back after he has been driven away, he is a different person. He isn’t coming back for external reasons. He comes back because his neshamah tells him to. That’s the power of a Megillas Rus Jew.

“Luli, a lot of Jews out there are never given this opportunity. They are never rejected, never driven away — everything in their lives proceeds exactly as it should. But there are other Jews, holy neshamos, who’ve been expelled, but instead of taking the opportunity to come back, they move even further away. Luli, you and me — we’re halfway there. We’ve been given the opportunity to become more genuine Jews — Megillas Rus Jews. We no longer do things out of fear of what others will say or what they’ll think of us. We’ve been through all that. All we have now is the truth nestled deep within our hearts.”

My new friend paused a moment and continued. “Luli, I’m talking too much. Megillas Rus Jews are musical. Dovid Hamelech was the sweet singer of Israel. So I have a beautiful song for you, a niggun I composed when Hashem gave me the opportunity to become a Megillas Rus Jew. I’ll teach it to you.”

I began to sing along with him — we could have gone on like that for hours. Suddenly he realized the sun was setting and he had to leave.

“The next time I see you,” he said, “we’ll sit and learn the sugya of Bar Peda together. I remember that sugya from yeshivah, and do you know the most important line in the entire sugya? This is the line we’ll learn together next time we meet: ‘Rav Hamnuna said, the kedushah in them — where did it go?’ Know, Luli, that it makes no difference what happened to us until now. Our kedushah hasn’t gone away — it’s still with us.”

For several days, I reviewed that encounter in my mind over and over again, and then I made a decision: I would become a Megillas Rus Jew. I would take the opportunity to start again, from a place where I could never have been before. I began planning for my return. I had two weeks to prepare until the day I knew I had to be home — Shavuos. I organized my affairs, bade farewell to my friends, took a haircut, and purchased new clothes.

And then I waited impatiently for Shavuos to arrive.

***

The telephone rang. My mother picked up and asked all the usual questions. “Luli, how are you? How are you doing? Will you come home for Yom Tov this time, even for just an hour? What do you say, Luli? We miss you very much and we want to see you.”

“All right, Ima,” I answered. “I’ll come.”

“Are you teasing me, Luli?” she asked. “When are you coming? For how long? Maybe you should stay with us for a little while. We haven’t seen you for four years. You don’t have to feel obligated,” she hastened to add. “I’m just offering.”

“Ima, it’s fine,” I said. “I’ll stay as long as you want.”

“I don’t want to decide for you,” she said with the faintest glimmer of hope. “But maybe you should stay for your birthday. We’ll make a party, just like we used to. What do you say?”

“All right, Ima. I’ll stay for my birthday.”

My mother was ecstatic. “I’ll start getting ready!” she said. “Do you want to speak to Abba?”

Before I could answer, my father’s voice echoed over the receiver. “I’m hearing good news!” he exclaimed. “Baruch Hashem! What have you been mechadesh?”

After four years, I finally had an answer. “I have a few chiddushim, mainly on the words of Rav Hamnuna, ‘The kedushah within them — where did it go?’ We’ll discuss it when I get there.”

I don’t know if a Megillas Rus Jew can bring Mashiach, but one thing is for certain: He can definitely perform techiyas hameisim….

I returned home. My years of wandering were over. When I had left, I was a Matan Torah Jew, but the humiliation I had endured had sanctified me. Now I was returning as a Megillas Rus Jew, who cleaves to Torah despite rejection and humiliation. In spite of everything, I had finally chosen to stick to my truth.

That Shavuos night, I sat with my father and returned to Bar Peda with a powerful yearning — accompanied by a special melody of longing, a niggun that continued to transform me.

The next morning, we went to shul together. And since it was the leining from my bar mitzvah, I was honored with reading both from the Torah and the Megillah.

You know, after being up all night, people’s heads always droop during Megillas Rus. But for me, every word filled me with a newfound sense of life. Naomi tried to push Rus away, but Rus clung to her. I remembered where I had been just two weeks earlier, and I remembered the ethereal tune that we had sung together.

When I reached the words, “And Rus said, ‘Do not urge me to leave you,’ ” I read them with the tune we sang on the boardwalk — the niggun actually fit perfectly, and by the time people woke up and realized what had happened, I had moved on to the next pasuk and had resumed the regular trop.

Shimon, you’re the first person I’ve ever told the entire story to. I’ve shared parts in shiurim that I give in various “dropout” yeshivos, but you know, there they think it’s not real, that I’m just giving a shpiel, that they can’t really change.

But Shimon, you learn in a regular yeshivah, and you know that I mean what I’m saying. Whenever you feel the pain of embarrassment or rejection, take it as an opportunity to be a more genuine person. Use those opportunities — they don’t present themselves to just anyone.

Look at me — I’m not your typical person. Some people even think I’m strange. But a Megillas Rus Jew isn’t affected by those things. He cleaves to the kedushah that’s been infused in him, and he knows it’s a kedushah that will never be lost.

Nu, Shimon, I’ve said enough. Now let us sing a little bit.

***

To this day, that song — the niggun from the Tel Aviv boardwalk — continues to echo in the small ezras nashim on the second story of that neighborhood shul.

Because a Megillas Rus Jew never stops singing.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 710)

Oops! We could not locate your form.