A Sanhedrin in the City of Lights

| November 14, 2023In 1806 Napoleon called for an assembly of Jewish leaders to form what he referred to as a “Sanhedrin”

Title: A Sanhedrin in the City of Lights

Location: Paris, France

Document: French National Archives

Time: 1806–1807

AS the 18th century waned and the French Revolution swept away the old societal and political paradigms, the position of Jews in European society was on the precipice of being transformed. The Enlightenment had begun to challenge centuries of discrimination, sparking debates on citizenship and equal rights. For Jewish communities across Europe, emancipation was an erratic journey, marred by entrenched prejudices, secularization, and assimilation.

The Revolution ushered in a new age in France, and Jews living there received emancipation as a result. But it was Napoleon Bonaparte’s seizure of power in 1799 that ultimately led to revolutionary ideas spreading across Europe, leaving emancipation of Jews everywhere in its wake. The Napoleonic Wars ensued over the next 15 years until his final defeat at Waterloo in June 1815. To many Jews, he was seen as a liberator, offering the ideals of emancipation and equal rights as an answer to centuries of Jewish suffering in Europe.

But others felt suspicion and hesitancy toward the ideals of the Enlightenment and its promises of brotherhood among all. What would happen to tradition after the literal and metaphorical ghetto walls were torn down? What would happen to religious observance if Jews integrated into general society? And how would Jews maintain their communial identity if they were to be considered equal citizens of their respective nations?

Against this turbulent backdrop, Napoleon Bonaparte emerged as a complex figure — a conqueror and lawmaker whose contradictory attitudes toward Jews embodied his era. European suspicions about Jews’ loyalties to the state and their place within the fabric of the nation lingered. Napoleon faced age-old prejudices raised by anti-Semitic voices to prevent Jewish integration into larger society. Christian Europe historically viewed Jews as tribal, usurious, and unsuited for equal rights for a millennium.

The questions and doubts that blew in with the wind from the battlefields of the Grande Armée were to reverberate in Jewish communities worldwide into the modern era. Napoleon’s mixed legacy on Jews and their relationship to the state was best illustrated in his bizarre attempt to reinstate the Sanhedrin.

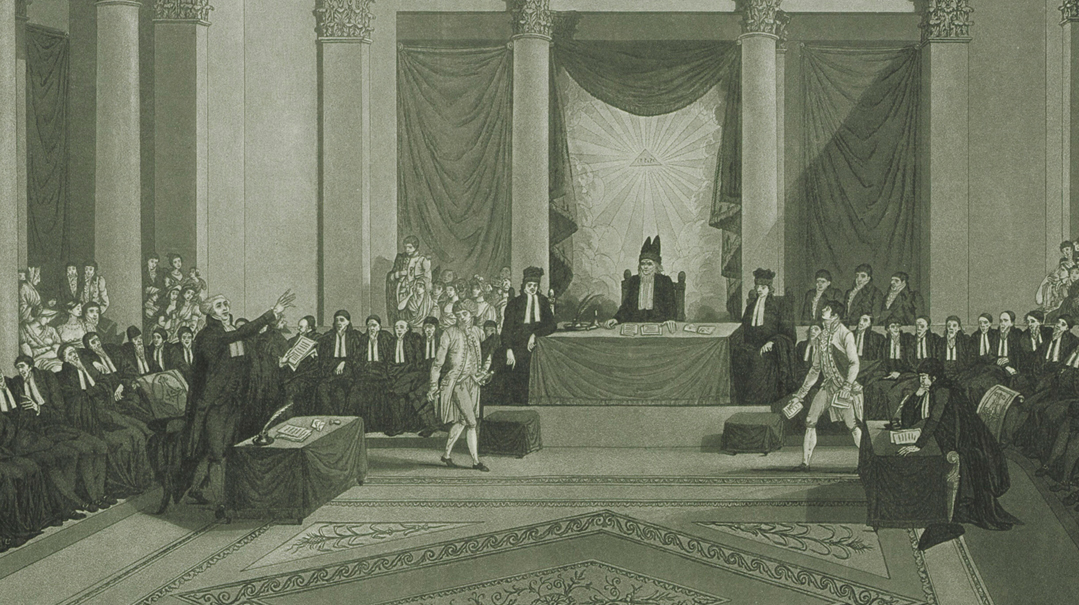

IN 1806 Napoleon called for an assembly of Jewish leaders to form what he referred to as a “Sanhedrin.” Napoleon’s use of the term “Sanhedrin” was symbolic, meant to evoke the ancient high court dissolved some 1,600 years earlier and thereby grant the assembly an air of authoritative Jewish tradition. However, the assembly’s true purpose was far removed that of from its ancient predecessor; it was not to decide matters of Jewish law, but affirm the compatibility of Jewish law with French law. Napoleon’s government submitted a list of questions to the assembly, to ascertain the stance of Jewish law and tradition on the state, its laws, relationships between Jews and non-Jews, and specifically practices of usury.

Composed of 71 members, like the Great Sanhedrin of Jerusalem, its members included rabbis, businessmen, and other respected figures. Rav Dovid Sinzheim, a noted Talmudic scholar, was selected as president. He was joined by Rav Yitzchak HaKohein Schwartz of Mainz as vice president and Rav Abraham de Cologna of Mantua. The members represented a cross-section of the Jewish communities across Napoleon’s empire, including the Italian and German lands under French control at the time.

While the Sanhedrin’s decisions had no legal authority under Jewish law, they carried significant political weight. Napoleon sought their endorsement to enact policies that would ensure Jews’ loyalty to the state. The Sanhedrin, under Rav David Sinzheim’s careful guidance, walked a fine line, trying to satisfy Napoleon’s demands without compromising halachah and Jewish tradition. The Sanhedrin’s responses to Napoleon’s questions were carefully worded. They affirmed the loyalty of Jews to the state, the prohibition of polygamy, and the willingness of Jews to embrace French citizenship and its responsibilities. These responses were crucial in Napoleon’s “Infamous Decree” of 1808, which imposed restrictions on Jewish commercial activities but also affirmed Jewish rights.

The Paris Sanhedrin was dissolved after its tasks were completed, but its legacy lived on. It had a mixed reception among European Jewry; some saw it as a step toward modernity and integration, while others viewed it as an infringement on Jewish autonomy. The event marked a significant moment in the history of Jewish and European relations, symbolizing both the opportunities and challenges of Jewish life in modern times.

The Development of the Yad Dovid

Rav Yosef Dovid Sinzheim (1745–1812) was born in Treves, France. A scion of the Maharal of Prague, he left an indelible mark on Jewish scholarship and communal life. As is evident from his magnum opus Yad Dovid, his Torah erudition was profound, and his leadership as rosh yeshivah in Bischheim was pivotal for Jewish Alsace. Rav Sinzheim sustained the tragic loss of his wife and the tumult of the French Revolution, which saw him relocate his yeshivah to safeguard its continuity. His wisdom extended to his community leadership in Strasbourg, where he deftly navigated the political maze to champion Jewish rights, dispelling accusations against Jews with diplomacy, and earning widespread respect. Rav Sinzheim’s legacy, etched in his scholarly works and his resolute communal advocacy, remains a cornerstone of Jewish historical resilience as a leader whose vision and fortitude transcended the challenges of his era.

Yashrus from Yeshivah

In 2016, Yeshiva University returned a collection of rabbinical manuscripts to the Auerbach family, represented by Rabbi Raphael Auerbach. These 23 volumes, valued at an estimated quarter of a million dollars, included rare works of Rav Dovid Sinzheim, whom the Auerbachs were descended from. Once housed in the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary, the manuscripts vanished in the wake of Nazi looting, only to reemerge in 1954 at a bookseller on the Lower East Side. The university’s decision to repatriate these texts without contention was a widely reported story that resulted in a kiddush Hashem.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 986)

Oops! We could not locate your form.