A Rose in the Ruins

| August 12, 2025“I would like you to visit Camp Eitz Chaim, a girls’ camp right outside of Moscow. You absolutely must visit this camp”

O

ne Shabbos between Minchah and Maariv in late spring of 2007, my friend Neal Nissel asked me, “Is there any chance you’ll be in Moscow at the end of July?”

“Well, quite possibly,” I responded. “Why?”

“If you are going to be there, I would like you to visit Camp Eitz Chaim, a girls’ camp right outside of Moscow. You absolutely must visit this camp. Your life will never be the same again.”

It has been almost 20 years since I had emigrated from the USSR, and 11 years since my wife and I became observant. After moving from Queens to Woodmere, Long Island in 1994, I’d gotten to know Neal Nissel, a local businessman and prominent member of the community. Together with other members of the Five Towns Jewish community, he’d graciously taken me under his wing as I found my footing as a religious Jew.

Neal played a crucial role in the resurgence of Jewish observance in Russia, serving as a board member of Operation Open Curtain for 25 years, together with Mr. Reuven Dessler and Rabbi Harry Mayer. He was passionately involved with the establishment and operation of yeshivahs and summer camps for Jewish children who had been disconnected from their heritage. Now, he wanted me to visit the girls’ camp where his two daughters were counselors, and he wouldn’t take no for an answer.

Turns out, I actually was going to be in Moscow at the end of July. My business had me traveling to the former USSR several times a year. But visiting a girls’ camp wasn’t on my itinerary.

He wouldn’t let me off that easily though. He emailed me again after Shabbos, and this time I owned up to my plans. But, I told him, I was flying out from Moscow to Siberia on Sunday and I really preferred to spend Shabbos in a quiet hotel downtown.

He wasn’t very fazed by my protests.

“You must spend Shabbos at the camp! I told you that if you come to the camp, your life will never be the same!”

Unable to withstand his heavy persuasion, I gave in.

Several weeks later, late on a Friday morning, I arrived in Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport where a camp driver picked me up. The traffic was horrendous and the drive took a few hours. Rabbi Berel Tsitsin, the camp’s administrator, called the driver’s phone to greet me and make sure that everything was okay.

The countryside scenery was familiar to me. A child of the late ’60s and’70s, I had grown up in Moscow, and had spent most of my childhood summers in camps outside the city.

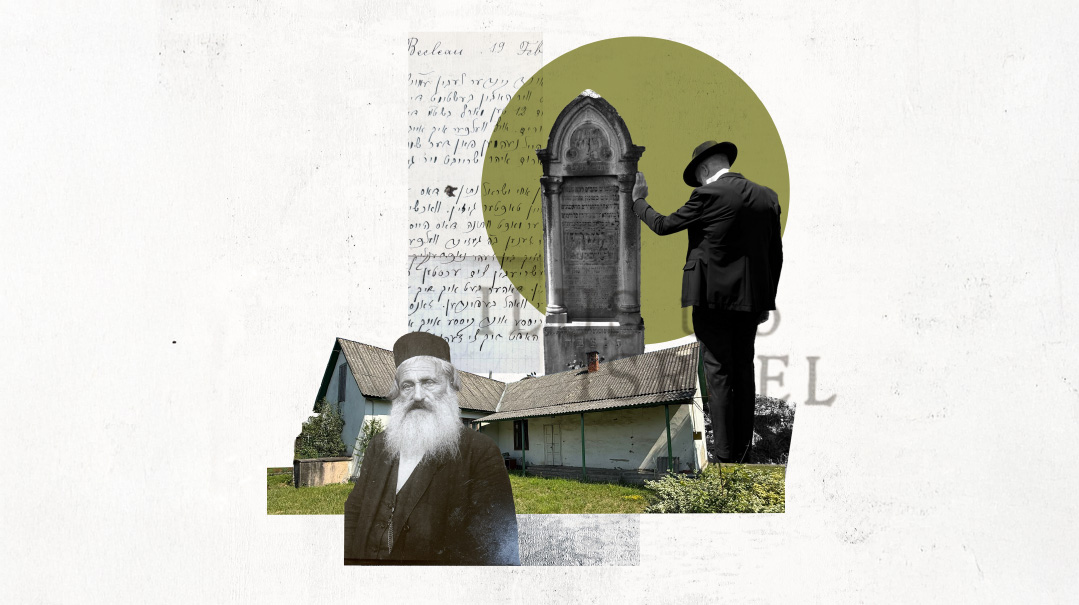

Eventually, we reached an old, run-down, former “pioneers” camp. (In the former USSR, all boys and girls from ages ten to fourteen had to join a mandatory Communist youth organization, and were known as pioneers.) Time had definitely left its mark. The roads were cracked and full of potholes, and the buildings had fallen into disrepair.

I myself had been a pioneer almost 40 years ago. But while my mind conjured up memories of boys and girls in scarlet neck scarves, my reverie was broken when I saw a slim, handsome man with a neatly trimmed black beard and a black velvet yarmulke standing at the gate and speaking on a cell phone. Introducing himself as Rabbi Rapaport, the camp rabbi, he greeted me cheerfully

Neal’s daughters, Rivki and Goldi Nissel, both camp staff members, came over to greet me. It was early Friday afternoon and even though candlelighting time would be only much later, the Shabbos preparations were in full swing. Girls were busy doing their nails and hair, cleaning up, and rushing to get a shower before the hot water ran out.

Rivki introduced me to Rabbi Rapaport’s wife, Chana Leah, who had been the director of the camp for the last nine years. Incredibly, she had managed to learn Russian on her own, enough to deliver sophisticated lectures.

The Rebbetzin volunteered to give me a tour of the camp, and as we walked around, childhood memories flooded my mind. I saw commemorative statues of Lenin and other founders of the Soviet Union in poor condition after years of neglect, and visualized a bunch of boys and girls yelling, “Lenin reigned, Lenin reigns, Lenin will always reign!”

And now, in the ruins of what had once been a prosperous Soviet empire, grows a beautiful Jewish “rose.” And with even more passion, these Russian girls declare, “Hashem reigns, Hashem has reigned, Hashem will reign for all eternity!”

A

fter my tour I got ready for Shabbos, and availed myself of the remaining hot water. Then I went to the cafeteria, where banners and posters showing Russian transliterations for netilas yadayim, Bircas Hamazon and pictures or collages of Purim, Chanukah, and other Jewish holidays were hanging right next to Soviet-era paintings depicting various scenes from Russian fairy tales. It was a stark visual juxtaposition of my past and my present.

One of the fine paintings showed a famous fairy tale called “The Frog Princess.”

Once upon a time there lived a Russian czar who had three sons. One day the czar called his sons and said, “My sons, let each of you take a bow and shoot an arrow. The maiden who brings your arrow back will be your bride.” Of course, as in every fairy tale the eldest and the middle sons got lucky and found good, noble brides, but the young Prince Ivan’s arrow fell into a marsh and was brought back by a frog. The first two brothers were joyful and happy, but Prince Ivan was in distress. How could he marry a frog?

“Please marry me,” asked the frog in a woman’s voice. “You will never regret it!” To make the story short, since you have probably already guessed that the story will have a happy ending, the frog turned out to be a beautiful princess who had been cursed, Prince Ivan removed the curse, and they lived happily ever after.

It was only after I returned to the US that I was struck by a new insight as to what that story means to me today. This fairy tale parallels the experience of Soviet Jewry under Communism, when carrying a Jewish identity was as unpleasant as marrying a frog. Only after the downfall of the Soviet Union and/or after emigrating were Soviet Jews able to discover the true beauty of their Jewishness.

Rivki suggested that I go to the cafeteria before Minchah and take a few pictures of the girls lighting candles. “There will be hundreds of girls lighting candles and you just have to see their faces,” she said.

I took her advice and followed the stream of girls, all dressed up, with the Shabbos spirit clearly present in the air and in their eyes. One by one, each girl lit candles and recited the blessing. I was awestruck. They did not see me, so nobody was posing or making faces. They were totally immersed in their connection with the Almighty. Nothing else mattered.

Afterward, I left the cafeteria and joined a very small group of men gathered there for Minchah. A few moments later, the girls began walking out. They were only ten or twenty yards away from us, but it seemed they were in a totally different world. They didn’t look at us. They didn’t see us. They were holding hands and walking in circles singing Shabbos songs, and it was not at all clear to me whether the girls were singing Shabbos songs or the Shabbos songs were being sung by angels Upstairs.

We sat down for Shabbos dinner.

At one point, Rivki asked me to come to her table and say a few words. I was really not prepared. Overcome by feelings and images of my present and my past, I found it difficult to speak and just said something about spirituality and how the spirituality here at the camp was tangible to me.

The next morning, I realized what I had really wanted to say. I would talk about women’s spirituality, the uniqueness of the camp counselors, and the impact of the experience on the campers and the staff.

I’d suggest to anyone looking to explore the topic of spirituality and women, to first buy a round-trip ticket to Moscow, and spend just one Shabbos at Camp Eitz Chaim.

The counselors’ dedication was unparalleled. They were fully cognizant that for many of the campers, these 21 days comprised their Jewish life for the entire year. These three weeks were like a “crown of the year,” allowing them to experience a true connection with the Creator, something that is difficult to maintain afterward when they come home to their totally secular or even anti-religious families. The counselors, in turn, try to squeeze into this short three-week window all their love for Judaism and for the Creator, and to instill Jewish values in the campers, understanding there will be no other chance and no other time to do it.

Speaking to some of the counselors, mostly religious girls from the US or Canada, I found it fascinating to hear their impressions. The 30 or so girls who come as volunteer staff are handpicked from a group of about 80 applicants. They commit to covering the cost of their airfare, and many of them use their own money to buy camp supplies and treats. Even once they return home, they stay in close touch with their campers by phone and email, assisting them in whatever way they can.

They all said the same thing: They leave as different people than they were when they came. The campers probably make as strong an impact on the counselors’ lives as the counselors make on the campers. It’s like the old Jewish question of whether the Jews keep Shabbos or Shabbos keeps the Jews.

ON

Motzaei Shabbos nobody went to bed. The girls were too wired. In just three days, camp would close its doors, and most of the girls would go back to their routine, irreligious lifestyles, with their non-observant families and friends. They would start counting the days until the next summer, the same way Jews count the days of the week remaining until Shabbos.

And for me, well, yes, Neal was right. Spending Shabbos in the camp was a truly life-changing experience. I had spent the first 30 years of my life in Russia, totally disconnected from anything Jewish, without any rudimentary understanding and knowledge of what Jewish life and traditions are all about. I knew nothing about the Jewish holidays, circumcision, Jewish marriage, or any of the mitzvos.

Now, I was on a journey to return to my roots and take my place in the chain that was completely cut off for three or four generations. Spending Shabbos in a Jewish girl’s camp outside of Moscow allowed me to “reclaim” the Jewish childhood that had been stolen from me by the oppressive regime of Communist Russia. I am forever grateful to Neal for this life-changing experience. It was mind-blowing to visit the camp, so reminiscent of the places where I myself once spent time as a Communist youth group member, and to see a rose growing in the ruins and a new generation experiencing what mine was totally deprived of.

In memory of my dear friend, Neal Nissel, Nissan Yaakov ben Shlomo Meir, who was niftar on 10 Sivan. He touched countless lives through his unwavering support for the Jewish community. May his memory be a blessing.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1074)

Oops! We could not locate your form.