A Reach Spanning Generations

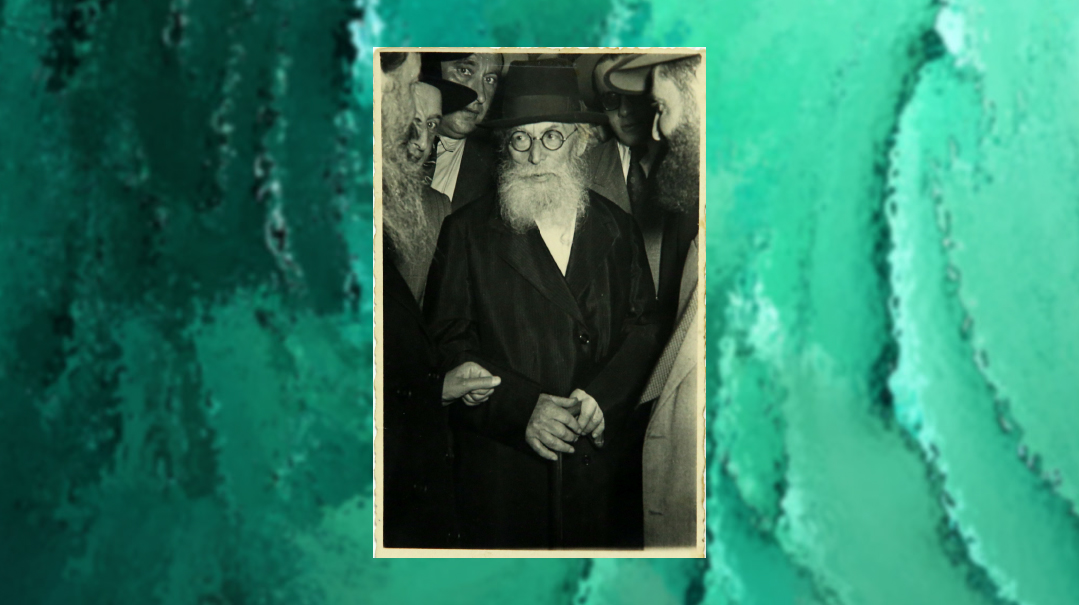

| December 5, 2023The enduring impact of the Chazon Ish

He guided Torah Jewry’s complex relationship with a vehemently secular state, created parameters for tenacious farmers to keep shemittah, tackled issues relating to Jewish service providers on Shabbos, and established a system of universally-accepted halachic measurements. Yet when the Chazon Ish came to Eretz Yisrael as a humble, anonymous avreich, no one even knew who he was

The Chazon Ish passed away decades ago, but his impact still permeates so many areas of frum life in Eretz Yisrael today. Far from a larger-than-life personality, this short, frail gadol was neither a rav or rosh yeshivah, and never sought the limelight. But his clarity in Torah, in both halachah and hashkafah, had Jews from all walks of life seeking him out.

He devised systems to help farmers keep Shabbos and shemittah, he redefined the halachic status of electricity, and identified esrogim whose pedigree wasn’t questionable, which are sought out even today. And the principles he formulated to navigate the divide between the religious and the secular still guide the fragile status quo. Seventy years after his petirah, a look back at the imprint of the gadol who shaped the halachic, hashkafic, and ideological contours of Eretz Yisrael until today.

Under His Wing

Rav Avraham Yeshayahu Karelitz was born in 1878 to an illustrious rabbinic Lithuanian family, but his path to greatness veered from that of many of his peers. While the vast majority of gedolim of the last century were products of the main yeshivos of prewar eastern Europe, the Chazon Ish, who began learning in a small yeshivah setting in Vilna under the guidance of Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski (though others are of the opinion that he set out to learn in Brisk under the Beis Halevi, Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik,) was only a yeshivah bochur for several days.

Scholars debate why this was so, some positing it was because of his strict adherence to the laws of chadash (which prohibit the consumption of wheat grain and consequently bread during certain months of the year), that proved difficult in a yeshivah setting. Others claim that the bochur, who was quiet by nature, was more comfortable with the solitude of his home.

This reticence was also evident in later years, as the Chazon Ish almost never spoke in public. This tendency seems to run in the family — it’s common knowledge in Bnei Brak until today that members of the extended Karelitz family never speak in public.

In any event, the Chazon Ish did not find his place in yeshivah, and generally learned by himself or from his father, Rav Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz, the rav of Kosava.

The Chazon Ish also suffered from ill health from a very early age. In a frequently quoted letter, the Chazon Ish describes never having enjoyed anything in life “aside from doing Hashem’s will.” An additional sad chapter in his life relates to his marriage: The Chazon Ish realized early on that he would never merit to have a child with his wife.

Aside from dealing with his own heartbreak, the Chazon Ish was constantly concerned with boosting his wife’s spirits. Rav Menachem Cohen (rosh yeshivah of Toras Chaim, elder Ponevezh talmid and chairman of the Mishpacha rabbinical committee), who learned as a young bochur in a yeshivah ketanah in Bnei Brak, says that the Chazon Ish frequently asked him to come to the house and ask the Rebbetzin for food or to fix his clothing, in order to give her the joy of providing for a child.

In fact, the Chazon Ish’s childlessness may have contributed to his lifelong mission of taking young teenagers under his wing and caring for their spiritual upbringing. In the beginning these were local boys from his town, such as Rav Moshe Illovitzky-Cohen (Rav Menachem Cohen’s father) and others, including the famous Yiddish writer Chaim Grade, who described the Chazon Ish in glorifying terms in one of his novels, as the “Machzeh Avraham,” a play on words on “Chazon Ish.” Recently, a fascinating collection of letters to one of these children, later known as Dr. Tzvi Yehuda, was donated to the Israel National Library.

Later in life, he took his nephews under his wing, and they eventually became his premier talmidim, conveying his traditions and teachings to the next generation. These illustrious students included Rav Chaim Kanievsky (son of the Chazon Ish’s sister who married the Steipler); Rav Chaim Greineman (son of his sister who married Rav Shmuel Greineman, menahel of Yeshivas Tiferes Yerushalayim in Manhattan); Rav Nissim Karelitz (son of his sister who married Rav Nochum Meir Tzibolnik-Karelitz, who assumed his wife’s maiden name due to border concerns); and Rav Meir Greineman shlita, author of the multivolume Imrei Yosher on Shas and a younger brother of Rav Chaim Greineman. Rav Meir enjoyed a close relationship with the Chazon Ish, as his father traveled abroad frequently for klal endeavors. As a child, he spent several years in the Chazon Ish’s home in Vilna and then as a teenager in Bnei Brak.

Oops! We could not locate your form.