A Privilege, Not a Burden

He was a giant who didn't fit into any of the familiar boxes, a fearless mouthpiece of timeless Torah truths

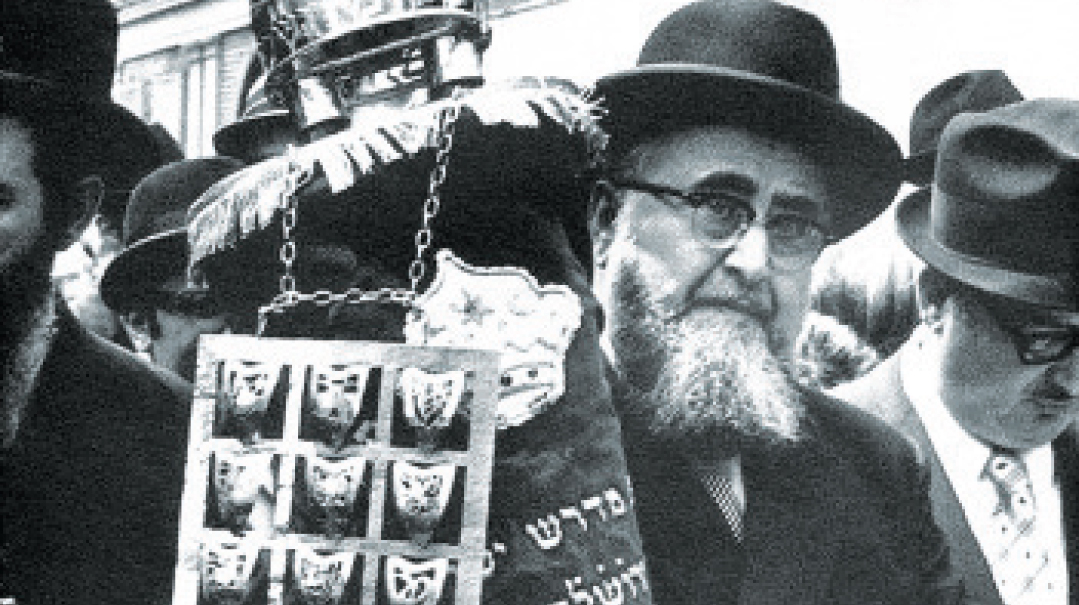

It’s a time-honored tradition to start tribute articles with a pithy remark or a short anecdote that neatly encapsulates the character of the person the author is about to introduce. But it's nearly impossible to single out one vort or story that could encapsulate Rav Shimon Schwab, whose 25th yahrtzeit, on 14 Adar I, was commemorated on Purim this year.

He was a giant who didn't fit into any of the familiar boxes, a fearless mouthpiece of timeless Torah truths whose message was not limited to the trials of a specific locale or generation.

Yekkeh, yeshivahhman, rav, lecturer, author, father — all fall short of summing up the essence of a man who managed to distill the best of many worlds into a single, intense life. Rav Schwab used to quip that a single mesorah is insufficient to deal with the complexities of the modern world; today's Jew needs the learning of the Litvaks, the joy of the Chassidim, the scrupulousness of the German Jews, the generosity of the Sephardim, and the simple sincerity of old-time American Jews.

Himself the product of more than one educational stream, perhaps his most precious legacy to a Torah world under threat is his joyous wonder at the precious gift that is Torah and his supreme confidence in its ability to light the way for all times.

A Privilege, Not a Burden

Rav Schwab’s son, Rav Meyer, who has served as dean of Bais Yaakov of Denver for 52 years, learned from his father the critical ingredient of successful chinuch: teaching our young people pride in their heritage.

In 1952, young Meyer read avidly, along with the rest of the world, about the grandiose coronation festivities of a young princess named Elizabeth, who at age 26 was assuming the throne of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. The crown jewels, it was reported, weighed some 20 pounds, and the new queen would wear them for several hours during the ceremony at Westminster Abbey. “I didn't understand how a young woman could sit for hours under that kind of weight. My father said, 'You know, you're right; they're very heavy. But I guarantee that at that moment she wouldn't change places with anyone in the world.' " For Rav Meyer, his father's message was clear — and is one he strives to impart to generations of students: It may not be easy to be different, but you become royal.

A Young Mind

Rav Schwab, for all his brilliance, was never static. He learned and grew along with his congregants and children.

"He used to say that the sign of an old man is that once he makes up his mind, he doesn’t change it again," remembers his eldest son, Rav Moshe Schwab, a long-time Boro Park resident. "His was a youthful mind. He was willing to make changes if he saw he was wrong in certain situations."

Rav Schwab spent many years working on the problem of “the missing 168 years,” a discrepancy between the timeline of Chazal and the academically accepted chronology of Persian history around the beginning of Bayis Sheini . After years of work and advancing several potential solutions, he decided that none of his answers were sufficient. "I would rather be honest and leave a good question open, than risk giving a wrong answer," he wrote.

While he believed that secular wisdom had value as a manifestation of Hashem’s creation, Torah’s eternal truth far surpassed any scientific merit, and one had to be prepared to offer one’s intellect as an Akeidah, if unable to reconcile a Torah truth with current scientific understanding.

This intellectual honesty was a hallmark of his life's work, says Rav Moshe. Perhaps the most public instance in which he evinced this iron commitment to truth was his evolving position on the balance of Torah and secular wisdom in a Jew's life. A product of Frankfurt, home of Rav Hirsch and bastion of Torah im derech eretz, he gravitated at a young age to the Eastern European yeshivos with their exclusive immersion in Torah. Fired by their zeal, he wrote a book titled Heimkehr Ins Judentum (Coming Home to Judaism), arguing that Torah im derech eretz had been a provisional response to the threat of the liberal movements, but it wasn’t suited to the long-term spiritual health of the community. Consistent with that position, he became one of the few rabbis in Germany without a university education. (He had, in fact, not even graduated high school.)

Later in life, he concluded that while the Jewish community needed the Torah-only approach of the yeshivah world, that was not the only path; the Torah-true balabos who engaged with the world while keeping Torah as his focus was also a hero to his people. Articulating this duality, he penned a book called Eilu v'Eilu, which validated the merit and necessity of both paths.

"He was sincerely of the opinion that Torah im derech eretz, if applied properly, was not an excuse for watered down Judaism. It is a challenge for intensified Judaism," clarifies Rav Moshe. "And it is applicable to all times and all generations." Rav Schwab was greatly pained by those, whether on the left or the right, who considered this venerable path to be a shortcut.

“As little children, when we were asked what we wanted to be when we grew up, he made sure our answer wasn’t a doctor or lawyer or other profession,” remembers Rav Moshe, who is himself a talmid chacham and owner of an eponymous insurance agency. “He’d say, ‘Your answer should be a talmid chacham and Torah-observant Jew. What you do for a living is separate from what you want to be. Your profession is not who you are.’ ”

Practicing what he preached, Rav Schwab steered his sons to institutions where they would grow, but never demanded a particular path, remembers Rav Meyer. Himself a product of Chaim Berlin (“If you go to Rav Hutner you will find a mechanech,” his father said), Gateshead, Rav Michel Feinstein, and Knesses Chizkiyahu under Rav Elya Lopian, his father was always his rebbe muvhak, guiding him in the direction that most suited his unique makeup.

A Friend and Protector

A mechanech par excellence, Rav Schwab adapted his approach to chinuch as changing times dictated. Never a dogmatic doctrinaire who insisted on doing everything the way it had always been done, Rav Schwab’s approach to a Torah life was dynamic, with a clarity of vision that enabled him to determine clearly which were immutable Torah principles and what was cultural chaff that could be discarded as times changed.

As a young father, he practiced corporal punishment, but later in life concluded that it was no longer an effective tool. In today’s world, he believed, hitting children risks closing down communication between parent and child, destroying parental influence. “He apologized,” recalls Rav Meyer. “He said, ‘I’m sorry for every spanking I gave you,’ and I answered, ‘I’m thankful for every spanking.’ I appreciated that he meant it only for our good.”

Rav Scwab’s chinuch was uplifting, empowering, and most of all, effective, recall his sons.

I hear the broad smile in Rav Meyer’s voice as he recounts his father’s solution to the problem of teenage boys having a hard time getting up for Shacharis. Rav Schwab was disappointed with his teenage sons’ penchant for sleeping late, but he recognized that berating them would be ineffective — or make things worse. “One day, he announced he would not say anything to us about it anymore,” remembers Rav Meyer. “He said he would record in his diary whoever did not come to shul. ‘And it will be there forever,’ he said. That did it.” Tardy shul arrival became a thing of the past in the Schwab household. Years later, after their father’s passing, the grown sons found themselves in their father’s diaries — but not the way they expected. “He would write, Moshe was in shul today. Yosef was in shul. He never wrote who didn’t come. His love came through.”

A master mechanech, Rav Schwab’s influence on his family wasn’t through lecturing or direct instruction.

“Our main chinuch was at our Shabbos and Yom Tov seudos,” says Rav Moshe. “During the week, he was always busy with his rabbinic and communal duties, but on Shabbos and Yom Tov he would sit at the table for two or three hours, discussing Torah, singing, telling stories, conversing with our guests.” Rav Schwab, who had a beautiful tenor voice and an appreciation for music, composed several tunes for the zemiros.

The Schwab table was often filled with guests, including gedolim, prominent intellectuals, and the poor and simple. Conversation was adult; the children listened in and learned their father’s personal history and his stances on questions of Jewish thought and the communal issues of the day.

“The time he made a special point of addressing the children directly was at the Pesach Seder. Usually, the guests sat near the head, with the children further down. Seder night, he’d place the children at the head and make an announcement —‘I apologize to the guests, tonight I am addressing myself to the children, they are the object of the Seder: v’higadeta l’vincha.’”

One Seder in particular remains seared into Rav Meyer’s memory.

It was sometime after the second cup of wine, and some of the children were already a little giddy, laughing a bit more than the sublime nature the night warranted. “He turned very serious,” recalls Rav Meyer. “He grabbed hold of his kittel and said, ‘In this kittel they will bury me! Tonight I’m here to tell you that this story is no myth, no legend, it really happened. If it were the last day of my life, I would tell you this story, because it is emes.’ It became a very solemn moment. And then he returned to his very jovial self, after having put the fear of the L-rd into us.”

Apart from these occasional glimpses of grandeur, the Schwab home was a light and joyful place to grow up. Grandson Rav Aron Yehudah, today a rosh kollel in Denver as well as an assistant dean in the Bais Yaakov headed by his father, Rav Meyer, was privileged to spend a year boarding in his grandfather’s New York home, in addition to learning b’chavrusa with him every summer as a child, when Rav Schwab would visit his family in Denver. “He used to make us laugh. He had an excellent sense of humor,” remembers Rav Aron Yehuda. “He used to quake when he laughed. He was only kind, warm and loving, even when I got into trouble in class.”

Reflects Rav Moshe, “My father used to say, when Yosef tells his brothers ‘vayesimeini l’av l’Pharaoh,’ Rashi defines ‘av‘ as chaver u’patron — a good friend and protector.” And his brother Rav Meyer agrees: “We considered him our best friend. The best times of our life were sitting at his table.”

The Whole Truth and Nothing but the Truth

Bentzion Ettlinger, today a senior analyst for the New York Power Authority, first became a student of Rav Schwab in Washington Heights’ Yeshiva Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, though he readily admits that as a high-schooler, he did not have the finely-developed appreciation of the Rav that maturity would bring. One day, when the young Mr. Ettlinger was chatting outside the shul with a chavrusah, the pair noticed the Rav exiting the shul. Deciding that such an eminent leader shouldn’t be left unescorted, the two walked him home, which sparked a 23-year relationship that Mr. Ettlinger says personifies Chazal’s adage, “Gedolah shimushah shel Torah yoser milemudah.”

“By the rav, I saw Torah in action, which profoundly affected my own personal life. A day doesn’t go by without seeing something that refers me back to something I witnessed by Rav Schwab or a devar Torah he would repeat.”

Possibly his most well-known attribute, Rav Schwab’s punctilious honesty was the stuff of legends. In the days before Turbotax, relates Mr. Ettlinger, Rav Schwab sold his house in Baltimore in order to move to New York and appointed a representative to handle the resulting complex tax return. Upon reviewing the Rav’s perfectly completed tax return, the awestruck IRS agent told Rav Schwab’s representative, “Tell your client we have never seen a tax form filled out like this.”

Another time, says Mr. Ettlinger, a questioner asked Rav Schwab a sh’eilah related to a frum Jew who was in prison for fraud, and Rav Schwab asked him to repeat the question. Thinking he hadn’t heard, the man repeated the phrase: “A frum Jew in prison.” Rav Schwab still seemed not to comprehend, until the questioner finally grasped that the Rav could not accept the idea that someone who could commit fraud could lay claim to the title of a frum Jew.

“Rav Schwab used to say, ‘Ninety-nine percent emes is 100 percent sheker,’” continues Mr. Ettlinger. “Someone once asked if he would write a memoir, but he declined, because his complete story would include lashon hara.” In Rav Schwab’s unwavering commitment to truth, he was unwilling to gloss over or leave things out.

Spreading Influence

In the 25 years since Rav Schwab’s passing, his influence has only grown, says Rav Moshe. A concrete fulfillment of Chazal’s dictum, “Gedolim tzaddikim b’misasan yoser m’b’chayeihen” (Chulin 7b), Rav Schwab’s Torah has been disseminated far more broadly now than it was in his lifetime. His Torah has been anthologized in the classic Maayan Beis Hashoeivah on Chumash, Iyun Tefilla (Rav Schwab on Prayer) and numerous other volumes on Neviim and Kesuvim, under the editorship of Rav Moshe, a fact which he modestly neglects to mention.

In all, more than 100,000 copies of his books have been sold to Torah students the world over. “His influence has spread much broader, wider and deeper since he has passed,” says Rav Moshe. “Many have called and told me that his works, especially on Tefillah, have been life-changing.”

To Rav Aron Yehuda, his grandfather’s legacy of unwavering truth is alive and well. “When he came to Baltimore, he was among the few people who were completely loyal to Torah and had to fight an uphill battle,” he says. “He would have such nachas from the Olam HaTorah which has grown on a straight path.” Kiddush Hashem, in its broadest sense, was Rav Schwab’s life work, and current initiatives dedicated to advancing the honor of Hashem , such as the Business Halachah Institute and Mifal Kiddush Hashem, would have been very dear to his heart, say Rav Aron Yehudah.

Teasing out a single thread that could sum up a rich and complex life would be difficult, says Rav Moshe, but ultimately, he sees his father’s legacy as the very human striving for greatness that Rav Schwab modeled daily. Although Rav Schwab revised his tzava’ah numerous times throughout his life, one constant never changed; in each iteration, he left instructions that his matzeivah bear the pasuk “He who covers his sins will be unsuccessful, but he who confesses and forsakes will receive mercy” (Mishlei 28:13).

“His mission in life,” says Rav Moshe, “was to make people aware that we are all human, with shortcomings and failings, but that everyone has the ability to rise to great heights if he makes a sincere effort to live in accordance with G-d’s Torah.”

In death, his call sounds as it did in life: urging us to face challenges head-on, without fear of failure; to tackle the seemingly insurmountable, confident in the infinite truth of Torah; to fall and rise again, trusting in the grace of a loving Father.

Sidebar

Born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany to Leopold and Hanna Schwab in 1908, Shimon Schwab was educated in the Hirsch-Realschule, founded by Rav Shamshon Refoel Hirsch, and later in the Yeshivah of Frankfurt. The young Shimon was just a teen when he was dazzled by the shiur of a visiting Lithuanian scholar by the name of Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman. Recognizing the bochur’s thirst for the deep lomdus of the Eastern yeshivos, the Ponovezher Rav directed the young man to Telz, where his three years of intense learning under the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Yosef Leib Bloch, were the happiest of his life.

Rav Shimon later applied for a visa to Palestine, intending to join the Chevron yeshivah, but the day the visa arrived, newspaper headlines screamed about a massacre of yeshivah students at the hands of Arabs. “He was a yeshivah bochur without a yeshivah,” says grandson Rav Aron Yehuda. Instead, Rav Shimon joined the yeshivah in Montreux, Switzerland, from where he later transferred to Mir to learn under the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, and the Mashgiach, Rav Yeruchom Levovitz.

Every step of the way, the young German bochur formed profound bonds with giants of the spirit. He was a member of the household of the Rabban shel kol bnei hagolah, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinsky, when the gadol was in Montreux, Switzerland; he cleaved to Rav Yeruchom; he spent time with the Chofetz Chaim. Rav Mordche Schwab, Rav Shimon’s brother, related that the Chofetz Chaim gave the young German visitor disproportionate amounts of his time and attention, foreseeing that he would be a leader in his new country.

In the late 1930’s, the young scholar was the district rabbi of Ichenhausen, Bavaria, Germany when he was singled out for special notice by the local Hitler Youth. After enduring harrowing persecution, Rav Schwab succeeded in moving his growing family to Baltimore, where he’d been elected rav of Shearith Israel Congregation, and where he remained for just over 20 years. While there, he fought the community’s liberal elements and waged pitched battles in defense of Shabbos and kashrus. In 1958, he was invited to join the rabbinate of Khal Adath Jeshurun, his native community.

There, he served under Rabbi Yosef Breuer until the latter’s passing in 1980, at which point he took the helm of the community until his passing in 1985.

Through his incredible life journey, Rav Schwab was primed to be a conduit to carry the lost Torah of Europe to a thirsty American public. The western European intellectual with the brilliant articulation and thorough self-education in all manner of subjects relayed Torah-true hashkafah from a lost world, all in a language they could understand.

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 804)

Oops! We could not locate your form.