A Page from His Book

Who are these talmidei chachamin who have dedicated their talents, time, and skill to disseminate someone else’s Torah?

Project Coordinator: Shmuel Botnick

Lifetime Contract

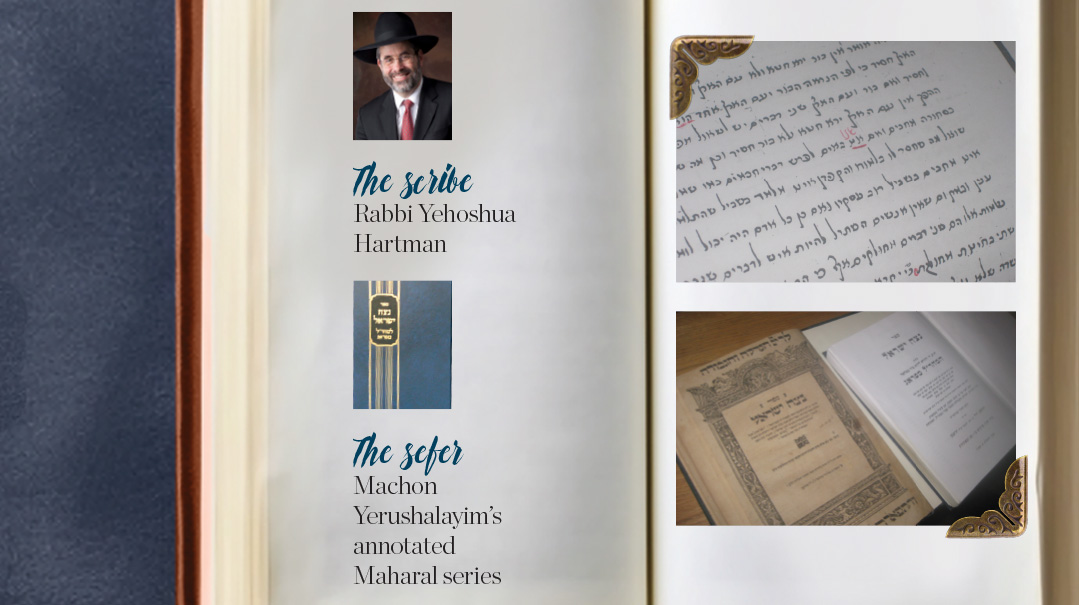

The scribe: Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman

The sefer: Machon Yerushalayim’s annotated Maharal series

Last week, Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman put out his 40th annotated volume of the writings of the 16th-century gadol the Maharal, Rav Yehudah ben Betzalel Loew: Drush al HaTorah, focusing on Matan Torah. The drashah was delivered on Shavuos 1592 in the Polish city of Pozna. As the 40 volumes to date attest, Rabbi Hartman has long since made peace with the fact that he has a “lifetime contract” with the Maharal, whose corpus of writing contains more words than the entire Talmud.

Even should he complete annotated volumes (actually multi-volumes) of each of the Maharal’s seforim, Rabbi Hartman is contemplating subsequent volumes in which he will gather all the Maharal’s writings on particular mitzvos — Shabbos, tefillin, bris milah, tzitzis, birchos haTorah, tefillah — and show how all the Maharal’s statements on that mitzvah derive from a common root.

The writings of the Maharal, Rabbi Hartman says, “are addicting. They open your mind and elevate you.” He points to Rav Yosef Engel, author of Atwan d’Oraisa, and one of the great lamdanim of the last 150 years, who attributed his entire method of learning to the Maharal.

Rabbi Hartman would be the first to admit that he did not discover, or rediscover, the writings of the Maharal, even though those writings fell into oblivion following the Maharal’s passing.

The Maharal’s towering stature was fully recognized in his lifetime. The Taz refers to him as the “gadol hador” (Y.D. 123). And his greatest talmid, Rav Yom Tov Lippman Heller, in his introduction to his monumental commentary on Mishnah, Tosfos Yom Tov, compares the Maharal’s impact on the study of Mishnah to that of Rabbeinu HaKodesh himself.

Once, Rabbi Hartman delivered a new volume of his annotated commentary to his then-neighbor Rav Ovadiah Yosef, and asked Rav Yosef about the Maharal’s stature in psak halachah. Rav Ovadiah immediately rattled off 40 or so places that commentators to Shulchan Aruch state that the halachah is like the Maharal.

Word of the Maharal’s wisdom even reached the non-Jewish world of his day. He met several times with the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and was invited to the palace of Emperor Rudolph II of Moravia. Even today, Rabbi Hartman points out, the Maharal is the only great rabbi whose grave gentiles wait in long lines to visit.

In his letter of approbation to Rabbi Hartman’s work on Nesivos Olam, the late Rav Shmuel Auerbach attributes the relative eclipse of the Maharal’s writings to the appearance in Europe of the astounding new kabbalistic insights of the Maharal’s younger contemporary, the Arizal, which were brought from Tzfas to Europe by the Shelah Hakadosh. Though there is no indication that the Maharal knew of Lurianic Kabbalah, legend has it that the Arizal said on his deathbed, “There is another like me in the West,” referring to the Maharal.

Not until 250 years after his death were the writings of the Maharal rediscovered by a line of Polish chassidus, extending from Peshischa to the Sfas Emes of Gur. Over the past century, the writings of the Maharal have been fundamental to virtually all of the most prominent baalei machshavah — Rav Eliezer Eliyahu Dessler, Rav Yitzchok Hutner, and more recently Rav Moshe Shapira, and ybdlch”a, Rav Yonasan David.

It wasn’t easy for Yehoshua Hartman to get Rav Moshe Shapiro’s haskamah, as the Rav had never given an approbation before

Rav Dessler gave a copy of Be’er HaGolah to his house bochur Rav Shapira when the latter was 15. Rav Moshe would say later that the Maharal formed the foundation of all his subsequent thought. And it is safe to say that Rav Hutner initiated his son-in-law Rav Yonasan David into the study of Maharal.

And it was Rav Hutner who first pushed the young Yehoshua Hartman to study the Maharal. In 1976, just a few months after the sudden passing of his father Rabbi Yechezkel Hartman, the 19-year-old bochur knocked on Rav Hutner’s door in Jerusalem’s Mattersdorf neighborhood in search of solace. The older Hartman had learned under Rav Hutner in Yeshivas Chaim Berlin from his bar mitzvah until the age of 28, and was one of Rav Hutner’s most prized talmidim.

Reb Yehoshua, who at age 65 retains all the boyish energy and enthusiasm of his young days, still remembers a humorous story about that first meeting. When he entered, Rav Hutner told him, “Shalom aleichem, farmacht di tir [close the door].”

Yehoshua, who did not speak a word of Yiddish, responded, “V’chein l’mar.”

Once Rav Hutner had overcome his surprise that the son of Yechezkel Hartman did not speak Yiddish, the two settled into Hebrew, which Rav Hutner spoke flawlessly, even correcting the Israel-raised Yehoshua’s grammar on occasion.

The two met every third Thursday for the next three years for several hours. Reb Yehoshua remembers those days with longing: “I’m sure that the pleasure of Olam Haba will be even greater, but you cannot begin to understand the pleasure of even the sichas chullin of Rav Hutner.”

While Rabbi Hartman did not rediscover the Maharal, he has unquestionably made his works accessible to a much larger audience. And he is perfectly content to have made his life work doing so. He cites a haskamah written by Rav Hutner. In that haskamah, Rav Hutner begins by celebrating those who save talmidei chachamim from the effort of searching for material so that they can devote themselves to deeper thought.

Rav Hutner then goes on to note that in the 26 “ki l’olam chasdo” series found in the Pesukei D’zimra of Shabbos (Tehillim 136), there are three distinct references to the creation of light: “to the Creator of great lights;” “the sun for rule over the day:” “the moon and the stars for rule over night.” Here we find, writes Rav Hutner (in the name of the Alter of Slabodka), that the same praise to Hashem for the creation of the great lights is also due for having ordered them in their proper time. So too is praise due to those who properly order Torah material so it is accessible to those seeking its depths.

Rabbi Hartman first started working on the Maharal’s Gur Aryeh, his super-commentary to Rashi’s commentary on Chumash, over a decade after Rav Hutner’s passing. At the time, there was not even a Chumash with Rashi and Gur Aryeh printed together. And the best version of Gur Aryeh did not even divide the commentary according to pesukim, or indicate in any clear fashion what words in Rashi Gur Aryeh was addressing.

Rabbi Hartman’s Gur Aryeh Chumash, published by Machon Yerushalayim, brought the Chumash, Rashi’s commentary, and the Maharal’s super-commentary together for the first time in nearly two centuries. In addition, Rabbi Hartman’s extensive notes referenced other prominent commentaries on Chumash and on Rashi, as well as sources in other writings of the Maharal that might cast light on the Maharal’s meaning in Gur Aryeh. (Today, Rabbi Hartman tells me, he spends far more time deciding what not to say in his notes than what to say, and he expresses a desire at some point to return to the first volume of the Gur Aryeh Chumash and revise it.)

Shortly after the first volume appeared, I made a post-midnight visit to Rabbi Hartman in his basement lair in Har Nof. I was then working on a Rashi project and needed Reb Yehoshua’s help with a certain Rashi.

Two things astounded me about that visit. The first was the collection of meticulous card files, which contained Rabbi Hartman’s well-organized notes on all the Maharal’s writings. It was still before computers were in widespread use, and before virtually every sefer became available online in one format or another. Rabbi Hartman admits that both developments have made his task much easier today.

The second thing that astounded me was that when we got stuck, Reb Yehoshua did not hesitate to call both Rav Moshe Shapira and Rav Yonasan David, despite the lateness of the hour. In our recent conversation, he mentioned the great respect the two gedolim — both capable of illuminating the meaning of the Maharal with breathtaking rapidity — had for each other. Rav Yonasan David told him that he and Rav Shapira had spent the whole night learning together on more than one occasion.

Reb Yehoshua jokes that as difficult as it was to complete his first volume, securing Rav Shapira’s haskamah was nearly as difficult. Until that point, Rav Shapira had never given a haskamah, and when Reb Yehoshua approached him, he asked, “What am I, the sar hahaskamah?” Eventually, however, a warm approbation was forthcoming.

Apparently, Rabbi Hartman still does not need much sleep. His phenomenal print output is not his principal job. He has been the rosh beis medrash at London’s Hasmonean School since 2007, where he has instilled a level of intensity in the Gemara learning to such a degree that Rav Shapira told him he could not return to Eretz Yisrael, despite almost his entire family living there.

Rav Yechezkel Hartman with Rav Hutner, with whom he learned for 15 years. His sudden death led 19-year-old Yehoshua Hartman to Rav Hutner’s door. “You cannot begin to understand the pleasure even of a mundane conversation with him”

The end of our conversation turns to the reasons for the enduring and growing influence of the Maharal. Here Rabbi Hartman’s always infectious enthusiasm waxes even greater. The Maharal’s great mission, he tells me, was to restore the honor of the chachamim, to show that their every word is precise. Not every statement in aggadeta is to be read literally, but each word, even the choice of the numbers, is precise, and the words of Chazal are true. The Maharal even devoted his entire sefer Be’er HaGolah to the explication of the some of the most perplexing words of Chazal.

Without the Maharal, says Rabbi Hartman, we would be embarrassed to quote these words to an intelligent gentile or unlearned Jew, because they sound so bizarre. With the Maharal, they become powerful beacons into the wisdom and precision of Chazal.

He quotes Rav Hutner on the difference between Christian and Jewish thinkers. The former struggle to find a place for G-d in man’s world; the great Jewish thinkers seek to locate man in Hashem’s world. The Maharal opens up the inner workings of Hashem’s world. He, again quoting Rav Hutner, reveals the secrets of nistar in the language of nigleh, creating in the process virtually an entire vocabulary all his own.

Reb Yehoshua offers one brief example of how the Maharal lifts us above simplistic understandings by referring to Nesiv Ha’Avodah (chap. 14) on Berachos 35a. The Gemara states than anyone who takes enjoyment from the world without making a brachah is likened to one who has appropriated sanctified property (me’ilah).

Many of us think of brachos as if we are saying “please” to HaKadosh Baruch Hu. But the Maharal explains that kadosh can only become chullin through a process of redemption (pidyon). So how does a brachah do that? Answers the Maharal: Everything in the world proclaims Hashem’s glory. And as such, we have no right to cut short its proclamation. But when we make a brachah on an apple, for instance, by referring to the One Who created the apple, we are continuing the apple’s purpose by another means, and are therefore permitted to eat it. The brachah is the act of redemption.

That is just one example among thousands of new understandings that the Maharal brought to the world, and which Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman has made available to an ever expanding circle of those who study his timeless words.

—Yonoson Rosenblum

Could an old volume of teshuvos revive the forgotten legacy of Rav Avrohom Aharon Yudelovitch after so many years?

Almost Forgotten

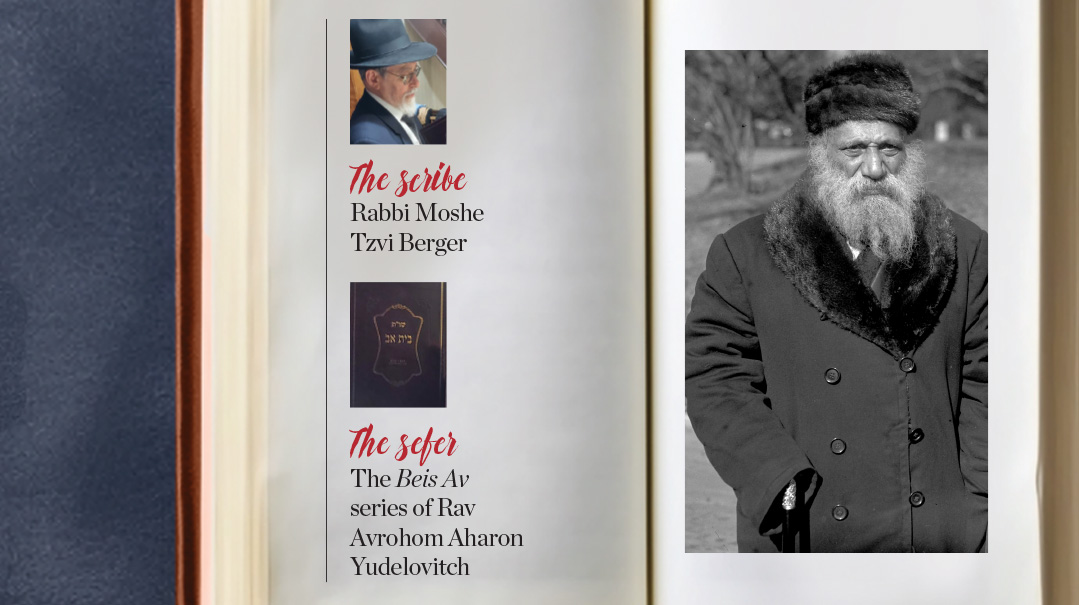

The scribe: Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Berger

The sefer: The Beis Av series of Rav Avrohom Aharon Yudelovitch

One afternoon in the mid-1970s, a young Mirrer talmid named Moshe Tzvi Berger walked into a Boro Park shul. Browsing through some old seforim, as he was wont to do, he stumbled on an old volume of Teshuvos Beis Av, a collection of halachic responsa.

As he read through some of the lengthy teshuvos, it became clear to Moshe Tzvi that this sefer could only have been written by a prodigious talmid chacham. The publication date was quite recent — just a few decades earlier — but the name of its author did not ring a bell. Eager to learn more about the mechaber, Reb Moshe Tzvi made it his business to find out whatever he could about Rav Avrohom Aharon Yudelovitch.

The early 1900s was a difficult time for the fledgling American Jewish community. Lacking the community infrastructure we take for granted today, European immigrants to the country struggled to meet their basic religious needs. The great rabbanim who came to serve this constituency found a rabbinate fraught with challenges.

Rav Avrohom Aharon Yudelovitch arrived on American shores in 1908 after holding rabbinical positions in Russia and in England. A towering talmid chacham and eloquent darshan, Rav Yudelovitch had studied in the Volozhin Yeshivah and received semichah from Torah giants; he was acclaimed for his mastery of Shas at a young age.

His career in America, spanning from Bayonne to Boston to New York City, would prove to be a consequential one. He stood at the helm of rabbinic organizations, presided over many public gatherings, and, for a time, held the unofficial title of chief rabbi of New York.

The greatest challenge of his career came in the late 1920s, when he was faced with a sh’eilah that would leave a lasting impact on his legacy. A childless woman was left widowed, and in order to remarry, she required chalitzah from her husband’s only brother who lived back in Russia. Since she had no feasible way to travel to him, Rav Yudelovitch devised an approach in which the chalitzah ceremony could be performed through a paid shaliach of the woman.

This bold psak drew the ire of the greatest rabbanim of the day. The resulting dispute greatly weakened Rav Yudelovitch and when he passed away in 1930, his reputation had been severely tarnished.

Forty years later, Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Berger embarked on a mission to uncover the rich Torah legacy of the nearly-forgotten Rav Yudelovitch.

A formidable talmid chacham in his own right who still learns in kollel full-time, Rabbi Berger devotes his free time to working on the ksavim of many bygone talmidei chachamim. (Among his ongoing projects are a fascinating sefer by Rav Nissin Markel of Buffalo, New York, called Binas Nevonim, which was extolled by Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, as well as the writings of Rav Wolf Leiter, a brilliant gaon who lived in Pittsburgh.)

In order to learn more about Rav Yudelovitch, he contacted his friend Rabbi Eliezer Katzman, a seasoned collector and eminent seforim expert, who led him to the library at JTS which houses many kisvei yad (handwritten manuscripts) from Rav Yudelovitch. Reb Moshe Tzvi became a regular visitor to the library, as he painstakingly copied anything new that he could find from the pen of Rav Yudelovitch.

Rabbi Berger began a scavenger hunt of sorts, looking for any clues that might lead him to more information about this forgotten rav. His quest brought him to New York’s Eldridge Street Synagogue, the last pulpit served by Rav Yudelovitch, and to the decrepit building on the Lower East Side where the rav had once lived (which, upon arrival, he deemed too dangerous to enter).

Rabbi Berger also searched the phone book for relatives and happened to make a call to a woman with the last name “Yood” who turned out to be a daughter-in-law living in the Brighton area of Brooklyn (the children had shortened their last name). Upon entering her apartment, Rabbi Berger discovered a woman well into her nineties; however, she had little to share with him beyond a family picture.

Throughout his research, Rabbi Berger became increasingly enamored of Rav Yudelovitch, and he dreamed of bringing the rav’s Torah to light, both by reprinting his old seforim, and also by publishing new ones based on the manuscripts he had left behind.

As Rabbi Berger’s foray into the world of manuscripts began, he made other discoveries as well.

At one point during his research of Rav Yudelovitch, he came across some old worn-out Gemaras with glosses in the margins. Upon further examination, he discovered that the Gemaras had belonged to none other than Rabi Akiva Eiger, and these glosses were an earlier version of his famed Gilyon Hashas. Rabbi Berger spent over a decade transcribing and annotating these glosses, which appeared in print in two separate volumes entitled Gilyon HaShas Miksav Yado shel Rabi Akiva Eiger. These discoveries, along with his full-time occupation as a lifelong member of the kollel of Mirrer Yeshivah, put his work on Rav Yudelovitch on hold.

But while the project was set on the back burner, it wasn’t abandoned. About 30 years after Rabbi Berger’s initial discovery, the time was finally ripe for him to publish the works of the forgotten scholar.

During the exhaustive research process someone challenged Rabbi Berger about his ambitions: Why revive the legacy of a figure who was so embroiled in machlokes? Perhaps it would be better to leave the project alone. Rabbi Berger, dismayed at this notion, made his way to the renowned Klausenberger dayan, Rav Ephraim Fishel Herskowitz, revered not only as a tremendous talmid chacham, but as an expert in seforim as well.

When Rabbi Berger shared his doubts about printing the seforim, Rav Herskowitz replied, “Have you seen his teshuvos in Yoreh Dei’ah? He doesn’t need to rely on the works of any Acharonim, his svaras are so good! He was a gaon and you should print his seforim.”

Rabbi Berger didn’t need to hear more than that. Indeed, Rav Herskowitz penned a glowing haskamah to the seforim, attesting to the gadlus of the mechaber. Rav Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg also wrote a haskamah, recalling the eloquence of Rav Yudelovitch’s drashos, which he had heard as a child.

Although it had been nearly 30 years from the day Rabbi Berger discovered the Beis Av until his dream of bringing these seforim back to light panned out, his fascination had not waned in the slightest. Even speaking to him today, one detects the youthful excitement that drives Rabbi Berger in his work.

The first sefer of Rav Yudelovitch that he reprinted is a peirush on Megillas Esther called Yad Hashem, was released in 2012. That same year, he printed a collection of seforim called Chiddushei Beis Av containing Rav Yudelovitch’s peirush on a part of the piskei halachos of the Rekanati as well as a peirush on hilchos tefillin of the Kol Bo.

Four years later, Rabbi Berger finally released the sefer that drew him in so many years earlier; a reissued edition of Teshuvos Beis Av in two massive volumes, containing the original five volumes published by the mechaber, along with an additional 85 teshuvos that Rabbi Berger discovered in manuscript form and are now available once again to the public.

(Rav Yudelovitch’s memory also merited revival via the popular Otzar HaChochma software utilized around the globe, where the first sefer in the inventory which serves as an opening screen is his sefer Av B’Chochmah, which addresses the aforementioned chalitzah controversy.)

As part of his efforts to revive the forgotten legacy of Rav Yudelovitch, Rabbi Berger makes an annual trip to Bayside Cemetery in Ozone Park Queens on 5 Shevat, to daven at the rav’s kever. True, he isn’t a relative or a direct talmid — but he feels a deep connection to these towering giants whose Torah came all too close to disappearing.

“There were so many great gedolim in America who we know so little about,” he explains. “Yet they left behind troves of Torah. We need to revive them.”

—Yehudah Esral

When Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky’s grandson discovered boxed of tapes of shiurim on Nach, it made the project much more complex, but the results were so much deeper

Voice of the Prophets

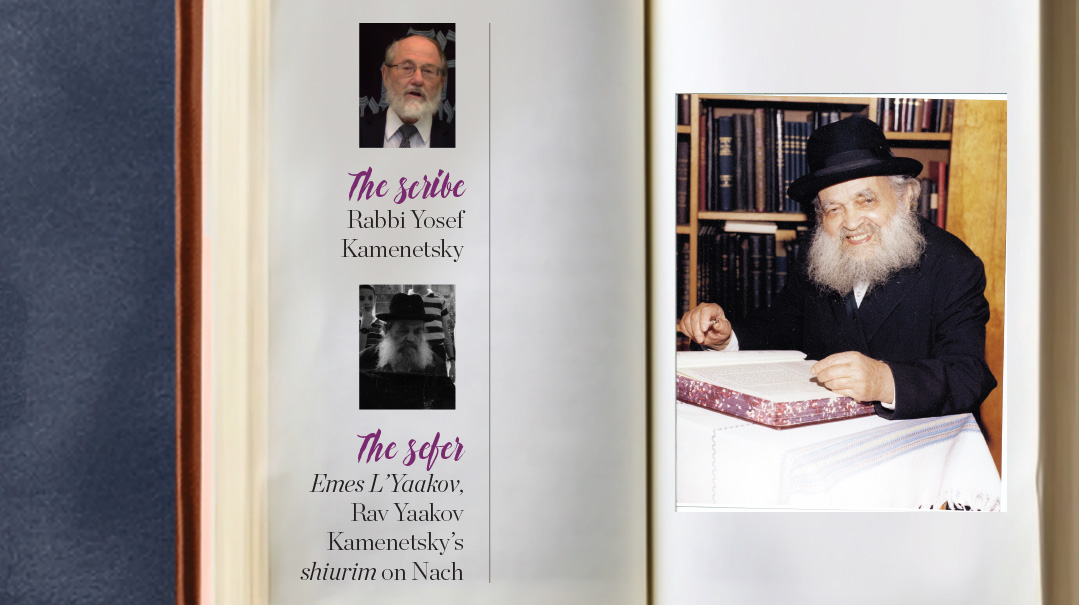

The scribe: Rabbi Yosef Kamenetsky

The sefer: Emes L’Yaakov, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky’s shiurim on Nach

Shortly after Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky was niftar in 1986, the extended family got to work publishing his many manuscripts as comprehensive seforim. The highly popular sefer, Emes L’Yaakov on Chumash, came from these manuscripts, as well as several seforim on Shas, all titled “Emes L’Yaakov.”

Rav Yitzchok Shurin, one of Rav Yaakov’s grandchildren, took on the responsibility of working with the notes on Neviim and soon enlisted the help of his cousin, Rabbi Yosef Kamenetsky, a son of Rav Nosson Kamenetsky a”h and resident of Jerusalem’s Sanhedria neighborhood.

The two cousins worked diligently — but found the project to be a slow and arduous endeavor. Both had fulltime jobs and Rav Yaakov’s writings were terse and not readily comprehensible.

“My grandfather didn’t gear these papers to the public,” says Reb Yosef. “He wrote the thoughts down for himself. He gave shiurim in Navi and would also review the entire Tanach every year.” The notations were simply meant to record the points of Rav Yaakov’s insights. “Decoding” them into a treatment accessible to the masses was daunting work.

A few years into the project, a transformational discovery was made. “One day, my cousin Reb Yitzchok showed up with a box of tapes — they were recordings of my grandfather’s shiurim on Sefer Melachim! I thought that that was the only set of tapes, but after I finished transcribing them, he showed up with another box and then another and another. Once I was well into transcribing the tapes, I realized that there were tapes on the entire Neviim Rishonim.”

These tapes made the project that much more complex and time-consuming but ultimately led to a more comprehensive product.

At this point, the project’s responsibility was left entirely to Reb Yosef and he spent hours listening diligently to the tapes, which were of poor quality. “I was working for ArtScroll at the time,” says Reb Yosef. “I worked on the translation of Rashi and Ramban on Chumash, besides many of the masechtos in the Hebrew translation of Shas, and I was getting paid by the hour. The time-consuming nature of working on my grandfather’s seforim was eating into my parnassah.”

A solution came by way of Rav Yosef’s father, Rav Nosson Kamenetsky. “My father fundraised on behalf of the Navi project and decided to pay me for my time,” says Rav Kamenetsky. So he began logging his hours and reporting to his father, who would compensate him accordingly.

Professionalism notwithstanding, the relationship was very much that of father to son. “Throughout all the years of work, my father was my sounding board. He would help me decipher various difficulties and offer me guidance, encouragement, and support.” The ideas contained in these manuscripts are advanced and the style ranges widely.

“A lot of the insights are based on dikduk,” says Reb Yosef, “so learning the sefer definitely requires a basic knowledge of Hebrew grammar. But there’s a lot of lomdus, drush, and several instances where my grandfather shares stories to bring out a point.” These stories are typically inserted in the footnotes.

Finally, in 2015, after close to thirty years of effort, a volume of Emes L’Yaakov on Melachim and all of Kesuvim was sent to the printer. There were no efforts to advertise its release — yet the 2,000 copies printed were readily sold out.

ITwas a great milestone, but it signaled a beginning more than an end. Reb Yosef now set out to work on his grandfather’s notes and tapes of Yehoshua, Shoftim, and Shmuel. “Although chronologically, I worked on these second, it’s still considered Volume 1 since, in order of the Sifrei Neviim, these come first.”

This second phase of the project took some eight years and has just been published in recent weeks. Aside from the monumental amount of work it entailed, the experience hit a painful bump in the road when, four years ago, on Erev Shavuos, Rav Nosson Kamenetsky was niftar. “My father had been with me throughout the whole project,” Reb Yosef reflects, “and his petirah was a real setback.”

But Rav Kamenetsky persevered, ultimately completing the sefer comprising Rav Yaakov’s insights on Yehoshua, Shmuel, and Shoftim. In addition to these three Sifrei Neviim, the new sefer also includes a section on Rambam’s Hilchos Melachim. “After my grandfather completed his weekly shiur in sefer Melachim, he went through Hilchos Melachim. My grandfather chose to learn this section of Rambam because of the many references in these halachos to pesukim in Neviim Rishonim, and so I added these shiurim to go along with his Torah on Navi.”

Reb Yosef’s affiliation with ArtScroll enhanced the project. “I was working on the ArtScroll Chumash with Ramban’s commentary,” he says. “One day, a FedEx truck pulls up in front of my home and drops off a box sent by ArtScroll. It was a set of tapes — my grandfather’s shiurim on Ramban. I listened to these tapes as part of my work on the ArtScroll project, but I heard many ideas that integrated well with his Nach shiurim. So I incorporated those ideas into the Navi sefer as well.”

It was an encounter that would be hard to write off as coincidental — and that was far from the only flash of Divine intervention.

“Many times,” says Reb Yosef, “I saw tremendous siyata d’Shmaya in my work. I could be struggling to understand something that my grandfather said or referenced and, all of a sudden, I’d come across a sefer that made it perfectly understandable.”

One story went beyond a glimmer of Divine direction; it was pretty much an all-out miracle. The story has some background.

Rav Yaakov, as is well known, possessed a great mastery of dikduk, Hebrew grammar. Upon completing all the work on this second volume, Reb Yosef wrote an introduction where he wished to include a story demonstrating how his grandfather’s prowess in dikduk actually guided a very important psak halachah. The problem was that he didn’t know the story.

“My father had told me that he had some vague knowledge of an incident where a rav wished to issue a lenient psak relevant to hilchos mikva’os. The leniency had something to do with his interpretation of the measurement of an ‘etzba.’ Rav Yaakov disputed the psak, demonstrating that it was inconsistent with proper Hebrew grammar.”

This would have been the perfect story to include in the introduction, but the details were too vague. Barring any breakthrough, the story would have to wait.

“Two days after Succos last year, my family went to Ein Gedi and wanted me to join. I’m not much into trips but, for some reason, I decided to go.” After spending an enjoyable time at the historical waterfall, the Kamenetskys began walking down the path that would lead them out of the site.

“As we were walking out, we passed an American couple walking in,” Reb Yosef recounts. “The husband looked at me and said ‘I recognize you!’ I didn’t recognize him at all. I said, ‘Well, my name is Yosef Kamenetsky, what’s your name?’

“The man’s ears perked at the name ‘Kamenetsky.’ ‘Are you related to Rav Yaakov?’ he asked. I confirmed that I was. He then told me his name, which did not ring a bell. We spent a few minutes trying to discover where we might have met each other.”

Turns out, they didn’t. The conversation ended unsuccessfully and the two parted ways, each walking in the opposite direction. All of the sudden, Reb Yosef heard a shout: “Hey, Rav Kamenetsky!”

He stopped and turned to see his newly discovered friend, now at a distance, calling him frantically. “Rav Kamenetsky! Do you know the story about the etzba?!”

Not quite believing what he had just heard, Reb Yosef rushed over to where the man stood. “Did you say etzba? You know the story about the etzba?”

“Sure I do! In fact, you can go to the OU’s Torah website where Rav Yisroel Belsky recounts the whole story.”

Rav Yosef headed back to Yerushalayim and made a beeline for his computer. It took him some time but he finally found a shiur by Rabbi Yisroel Belsky whose title had the word “measurements” in it. He hit play. “I was exhausted but I forced myself to stay awake. Finally, somewhere near the twenty-minute mark, I heard it! The whole story!”

In quick summary, there was a rav who had drafted plans for mikvaos that seemed small to other rabbonim. They questioned the rav’s calculations, but he staunchly defended his position. The rabbanim approached Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky who in turn met with the rav. Over the course of the conversation, the point of confusion became clear.

The Rambam says that an amah (the Biblical term for a cubit) comprises 24 etzba’os. The Rambam defines an etzba as the width of an “etzba beinoni.” The rav understood this to mean “the middle finger of the five fingers.” That being the case, the rav used an average middle finger’s width to determine the length of an amah, which he then used to calculate the dimensions of a mikveh. Rav Yaakov heard this and understood the problem.

The phrase “etzba beinoni” does not mean “middle finger.” It means “the finger [thumb] of an average-sized man.” Grammatically, “middle finger” is “etzba beinonis” with the adjective in feminine form, because the Hebrew word “etzba” is a feminine noun. The word “beinoni” in the Rambam’s phrasing is therefore not an adjective but a case of semichus or possession. In reality, halachah requires measuring with the width of the average man’s thumb — which is thicker than the middle finger. This shift in definition makes all the difference in evaluating the halachically required measurements.

Rav Yosef rewrote this entire story in Hebrew and added it to the introduction of the new volume, a fitting pièce de résistance to a true magnum opus.

— Shmuel Botnick

A Gift to the People

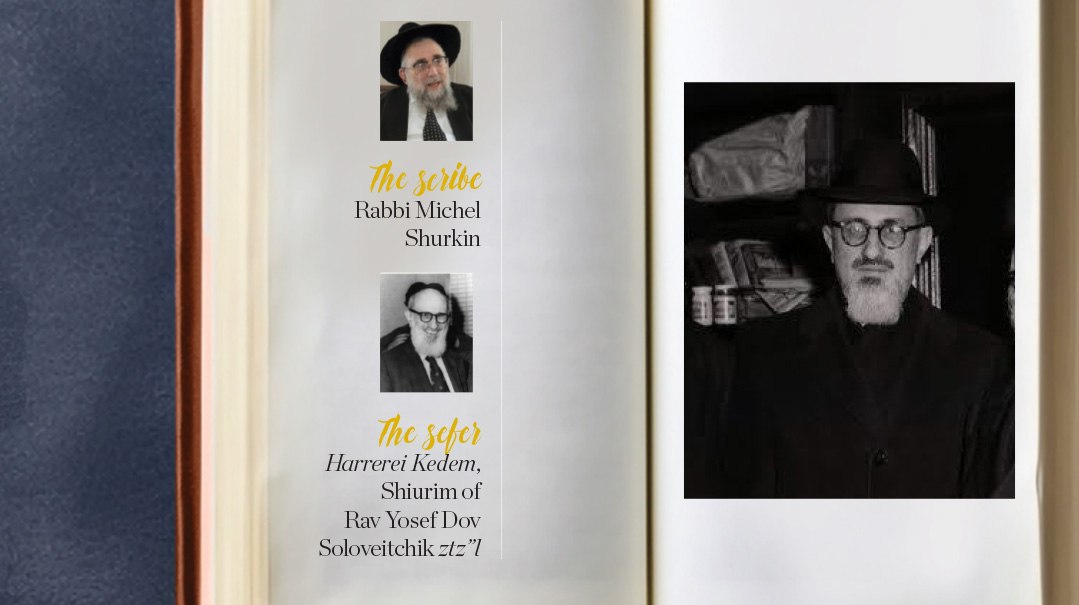

The scribe: Rabbi Michel Shurkin

The sefer: Harrerei Kedem, Shiurim of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik ztz”l

“IFyou could go back in time and listen to a shiur by any talmid chacham of the last century, who would it be?” a talmid once asked Rabbi Michel Shurkin, the venerated maggid shiur in Jerusalem’s Yeshivas Toras Moshe.

“Rav Yoshe Ber,” he responded without blinking.

“But what about—” the talmid tried to list names.

“Rav Yoshe Ber,” Rabbi Shurkin snapped back.

“Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik,” he enunciated one last time. He looked the talmid in the eye. “You don’t understand. He was in a different league. He gave us Torah MiSinai. The shechinah was speaking from his throat.”

ITwas on a Tuesday night in the early ‘60s when Reb Michel showed up at Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik’s shiur at the Moriah shul on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Dazzled by the presentation and content, Reb Michel knew that he had found his rebbi. For the next twenty-plus years, Reb Michel became a fixture in Rav Yoshe Ber’s daily shiur in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan, absorbing every word that left his rebbi’s mouth. During the summer break, Reb Michel would follow his rebbi back to Boston, and organize a kollel of talmidim to whom Rav Yoshe Ber would deliver shiurim.

Spending over two decades in the shiur of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveichik of Boston didn’t satiate Reb Michel’s thirst for his rebbi’s Torah; it left him craving more.

Decades later and thousands of miles away, Rabbi Shurkin’s talmidim in Toras Moshe get occasional glimpses of their rebbi’s true passion. At the outbreak of the corona virus in March 2020, when the yeshivah transitioned to remote learning, the yeshivah sent a technician to help set up a Zoom system for Rabbi Shurkin to give shiur. In order to test the sound system, they turned on an old shiur from Rav Yoshe Ber to see how it would project. Upon hearing the familiar voice of his rebbi, Rabbi Shurkin was immediately transported to a different time and place. He grabbed a pen and paper, and, engrossed in the shiur, meticulously copied over every word, just as he had done many decades prior.

But what propelled Reb Michel to devote hours of time to disseminating his rebbi’s Torah? “The rabim wanted it,” he explained. One can’t help but wonder if he is referring to the conversation with Rav Shmuel “Charkover” Vilensky of Beis Hatalmud, which is recorded in the hakdamah of the first chelek of the Harrerei Kedem.

Reb Michel was sharing a chiddush from Rav Yoshe Ber regarding the sugya of shadi nofo basar ikkaro (viewing the branches of a tree as an extension of its trunk), as it pertains to both an Ir Miklat (city of refuge) and techum Shabbos. After hearing the chiddush, Rav Shmuel sighed and said, “if only someone could share the Torah of Reb Yoshe Ber with the olam hayeshivos.”

This conversation left Reb Michel inspired to publish and disseminate the Torah of his rebbi and to make it available to lomdim who didn’t merit to attend Rav Yoshe Ber’s legendary shiur.

The initial efforts were printed as submissions to the journal, Hamesorah, printed under the auspices of the Rabbinical Council of America. Over the course of several years, Rabbi Shurkin published his notes from his rebbi’s shiur in the journal. Eventually these notes were collected, augmented with more material, and published as a separate series of seforim called Harrerei Kedem.

The first two volumes of Harrerei Kedem, which cover the sugyos pertaining to the Moadim, became instant classics, going through many reprints over the years. These seforim present the incisiveness and beauty of Brisker lomdus clearly and succinctly, providing Bnei Torah with the sweetness of the Rav’s Torah on parts of Shas that aren’t usually learned in yeshivos.

The first volume was printed in 2000, followed by a second in 2004. More recently, a third chelek covering the sugyos of Shabbos appeared in print in 2013.

Unlike many other contemporary seforim in which it has become common practice to dress the front of a sefer with lengthy introductions, haskamos, and biographical content, the Harrerei Kedem essentially dispenses with all frontmatter.

“Rav Yoshe Ber needs no haskamah,” Rabbi Shurkin says bluntly.

After a very brief introduction, without so much as a word about the mechaber, the sefer launches into siman alef, as if to say that the Torah itself speaks for the mechaber, and further detail is neither necessary nor particularly informative.

Why the name Harrerei Kedem? “It’s a secret,” he says.

Reb Michel’s insatiable appetite for the Torah of Rav Yoshe Ber is manifest in his publishing habits. He is constantly adding new material to the existing seforim. When he has accumulated enough new material, he reprints the sefer and includes the additional simanim in the back, compelling devoted consumers (read: subscribers) to keep up with the latest volumes.

Sometimes, Reb Michel will include the additions in the back of another of his popular works, Megged Giv’os Olam. The Megged, as it is referred to, contains stories and hanhagos of a number of gedolei Yisrael, many of whom Reb Michel knew personally, including his rebbi, Rav Yoshe Ber. In Rabbi Shurkin’s view, these stories are not mere tales of the greatness of these giants, but rather an extension of the Torah they taught via a demonstration of the Torah they lived. This fascinating and invaluable sefer, first printed in 1999, has also undergone many reprints and additions and currently contains four volumes. It is the source for many important psakim and minhagim, and it is quoted in many contemporary halachah and responsa seforim.

The Megged has earned high praise from talmidei chachamim and other connoisseurs of Torah literature. “I was told that recently, when Rebbetzin Bruria David a”h was very ill before she passed away, they read her stories from the Megged,” Rabbi Shurkin says.

Rabbi Shurkin gives a popular Chumash shiur on Fridays in Yeshivas Toras Moshe, in which he repeats his rebbi’s chiddushim on the weekly parshah. The chiddushim are collected from Rav Yoshe Ber’s regular shiurim, and Rabbi Shurkin hopes to print these in his next volume of Harrerei Kedem.

“I wrote the Harrerei Kedem as a gift to Klal Yisrael, to give the rabim what they wanted,” Reb Michel says. The avid interest in the multi-volume series attests to both the hunger of the masses and his skill in satiating them.

“But I was only partially successful,” he concedes. “I can give them the Rav’s Torah — but I can’t give them the experience of being in the Rav’s shiur.”

— Yehuda Esral and Boaz Bachrach

Mining Gems

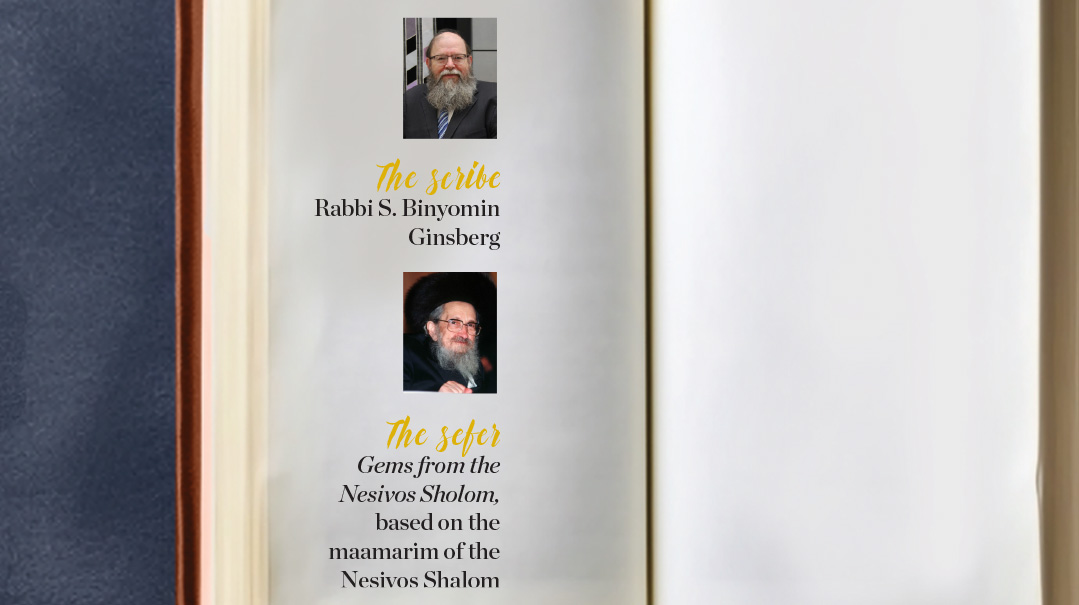

The scribe: Rabbi S. Binyomin Ginsberg

The sefer: Gems from the Nesivos Sholom, based on the maamarim of the Nesivos Shalom

R

Rabbi S. Binyomin Ginsberg considers Gems from the Nesivos Sholom, a series of nineteen volumes distributed by Israel Book Shop expounding on the maamarim of the Nesivos Sholom ztz’’l, Rav Sholom Noach Berezovsky (1911–2000), the previous Slonimer Rebbe, his life’s work. But while he’s devoted countless hours listening, learning, researching, reviewing, and finally elucidating his Rebbe’s maamarim to make this classic chassidishe work accessible to the general English speaking public, he freely admits that he was admittedly an unlikely candidate for the task.

An American-born native of Boro Park learning in Telshe, Cleveland, young Binyomin Ginsberg was following the typical trajectory of a young budding talmid chacham, trying to master the shiurim and works typical of those found in the great litvish yeshivahs. But his life took a turning point when someone introduced him to a sefer called Toras Avos, a collection of divrei Torah from the rebbes of the Slonim-Kobrin-Lechovitch dynasty.

The sefer, which had been compiled by the rosh yeshivah of the Slonimer yeshivah (son-in-law of the then-rebbe, the Bircas Avrohom, who succeeded his father-in-law as rebbe upon his passing in 1981 and was referred to with the title of his magnus opus, the Nesivos Sholom) exerted a magnetic pull on the young bochur. He read the stirring introduction – seemingly simple but layered with depth — and he was smitten. On the spot, he decided to go learn from this author.

Defying both logic and slight opposition, Binyomin flew to Eretz Yisrael for the next zeman, and the Telshe-educated, English speaking Boro Parker managed to gain acceptance to the Slonimer yeshivah, located in Meah Shearim.

If he still had doubts whether his unconventional move was right for him, his first Motzaei Shabbos in the yeshivah laid those fears to rest. The Nesivos Sholom had gathered the bochurim for a shmuess and his chinuch mastery was on full display. He addressed the issue of bochurim smoking, and rather than coming out full force against it, requested that should the bochurim continue to smoke, they should only do so in a clean, respectful manner.

Rabbi Ginsberg was inspired, both by the content, and by the Rebbe’s ability to gauge what his audience was able to hear, but also by the style: “I was taken by the softness in the voice, the clarity, and the ability to inspire, each one at his level,” remembers Rabbi Ginsberg.

And so began a lifelong relationship with the great Rebbe of Slonim.

Binyomin moved back to America and became known as Rabbi Binyomin Ginsberg, a premier mechanech in his own right. He was blessed with an uncanny ability to reach the hearts and mind of children – and blessed too, with an unparalleled rebbe.

And while he impacted children every day, he wanted to reach out to the older generation as well. He dreamed of sharing his rebbe’s writings, which had achieved universal acclaim among Hebrew speakers and those familiar with chassidish works, with the greater community.

Rabbi Ginsberg approached the Rebbe’s son (and current Rebbe) for approval, but the Rebbe was initially hesitant, concerned that Rabbi Ginsberg would not be able to accurately convey what the Nesivos Sholom meant in any particular maamar. Undeterred, Rabbi Ginsberg didn’t let up, and ultimately, the Rebbi granted his wholehearted approval. “He told me what kind of zechus I would have and gave me a strong brachah for hatzlachah,” Rabbi Ginsberg shares.

But upon receiving the coveted permission, Rabbi Ginsberg found himself overwhelmed — not so much with the task that lay ahead, but with the inherent responsibility. “I was filled with a profound sense of awe,” he says. “The responsibility weighed heavily upon me. I understood the immense impact these seforim could have on individuals’ lives, both in deepening their understanding of Judaism and enhancing their spiritual growth. It was a daunting yet exhilarating task.”

The first thing he did was daven. “I realized the crucial importance of constant tefillah. Each day, I fervently davened for continued success, seeking guidance and Divine assistance in presenting the Nesivos Sholom’s teachings with clarity and authenticity. Recognizing the magnitude of the task at hand, I sought the support of Hashem in every step of the writing process. Davening became the foundation that grounded my efforts and propelled me forward.”

Determined to ensure that his sefer would be true to the Rebbe’s intent, he immersed himself in the Rebbe’s shmuessen. Rabbi Ginsberg delved deeply into studying the original material, immersing himself in the teachings of the Nesivos Sholom.

“Learning the foundational knowledge formed the bedrock for the elucidations. It was a transformative experience for me,” he says. “I found myself thinking about the work every waking moment of the day. The teachings became intertwined with my thoughts, weaving themselves into the very fabric of my existence.”

Another daunting challenge, aside from retaining the essence of the Rebbe’s teachings, was preserving the compelling, profound style of the maamarim even in translation.

“I grappled with the challenge,” Rabbi Ginsberg admits. “It demanded careful thought and skillful writing.” Rabbi Ginsberg would write, backspace and then rewrite again. He also made sure to solicit input and feedback from others — especially talmidim of the Nesivos Shalom — before submitting his work for editing.

As the volumes were slowly released, the feedback he received validated the immense effort he had put into widening the reach of his Rebbe’s Torah. He recalls a particular letter that came in after the seventh sefer was released. It read as follows:

I felt this need to accomplish more spiritually in my life, make it to minyan three times a day and focus on the actual tefillah. I chanced upon your Yamim Noraim book and it was a life-changing moment. I approached Rosh Hashanah that year in a way that I never had before. Aseres Yemei Teshuvah and Yom Kippur felt so different than they had in the past.

I was excited to find the next volume of your series, which carried me through Simchas Torah and Parshas Bereishis. Davening could no longer go back to how it had been in years past. My wife joked with me that I should try explaining to people how I became a “minyan guy” at 43. The concepts of the Nesivos Sholom which you have elucidated so clearly have been an instrument of change for me and my family.

Naturally, feedback like this was tremendously gratifying to Rabbi Ginsberg. “Witnessing the impact of these seforim on readers, seeing their hearts and minds open to the timeless wisdom they contained, was a source of immense joy and fulfillment,” he says.

The seforim have become his life’s work, and he’s ever grateful to the numberoous individuals he worked with who dedicated their time, energy and resources to make it happen.

“Throughout the entire process, I was constantly grateful to Hashem. Recognizing that the ability to embark on this sacred task was a Divine blessing, I offer Him thanks each and every day,” he says. “It was an unlikely journey that reinforced the profound connection between the Creator and His creation, a reminder that the true source of inspiration and wisdom lies in Hashem Himself.”

— Yosef Herz

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 962)

Oops! We could not locate your form.