A Million Miles from Nowhere

| February 10, 2026I wasn't sure what I'd find in Okinawa, but I didn't expect a group of eager Jews

I didn’t expect to find an animated Jewish community at the ends of the earth, but it underscored how the pintele Yid isn’t constrained by borders

There are several places a frum American Jew might realistically expect to find a decades-old picture of his own grandfather.

Atop a pile of books being given away by a church congregation, in a military installation on a tiny island in the East China Sea, four hundred miles from nowhere… is not one of them.

But there it undoubtedly was, and there, as well, was I, staring at each other across 85 years and a thousand miles. The questions hanging heavy in the tropical island air between us were: Which of us had taken a more unlikely route to get here? And how had we both wound up at the same coordinates in the space-time matrix of this serendipitous universe?

Purim in Japan

I’d come to Okinawa, Japan, for Purim of 2024. Not as a Purim joke, or in pursuit of an elaborate costume or overblown mishloach manos theme, but for real: to arrange and lead the chag for the small but proud group of Jews living on the island. Setting out, I wasn’t sure what I would find — but a courageous small kehillah of Yidden absolutely thirsting for Torah definitely wasn’t it.

The trip from Lakewood to Okinawa took over 24 hours and included stops in Seattle, Anchorage, and Guam, before we finally landed at the largest of 160 islands in the Ryūkyū Archipelago, hundreds of miles from the nearest large land masses — Japan, China, and Taiwan. The Ryūkyū Islands stretch in an arc from the southern tip of the main Japanese islands, across the South China Sea and Pacific Ocean to Taiwan. Okinawa, the capital of this Japanese prefecture, is about 466 square miles with a population of 1.3 million.

Bleary-eyed and 14 time zones off-kilter, I was welcomed by two leering, grimacing monster faces, one twisted into something between a sneer and a smile, the other openmouthed and hungry.

Can you be delirious from exhaustion? Or was Japan really haunted by monsters?

Neither. They were Okinawan shisa dogs, twin statues that I quickly learned are the most common sight on the island. Locals have some superstition about them bringing good luck. They’re always set up in pairs — one with its mouth open and another closed.

To me, they’re just creepy.

As I stepped out of the terminal, I was greeted by a similarly perplexing scene. Streetlights here are a neon blue light, casting an eerie frosted glow over everything. This was going to take some getting used to.

News for the Jews

Were there Jews here? You bet. A private Facebook group called The Jewish Community of Okinawa features over 200 members. Not all of them are on the island at once — many are service members in the US military or students at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), a prestigious university in central Okinawa, and they cycle on and off the island. A cadre of Israelis can be found here as well — faculty at OIST, spouses of US military personnel, and even a few civilians who have taken up residence in Naha, Okinawa’s biggest city.

On my first evening in Okinawa, we announced a Torah class on the upcoming Yom Tov of Purim, and about ten people showed up. They were into it and involved, and it was clear they were thirsting for Torah and connection to their Jewish soul and identity.

Over the next few weeks, I conducted several classes, minyanim, and a Purim seudah. I met dozens of Jews, with a disparate level of observance. Some were secularized and unaffiliated, while many were deeply committed. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, living this far from any Jewish infrastructure had encouraged most to ask questions, explore their heritage — and for many, to take steps back.

Culture Shock

Other than being the definition of remote, Okinawa seemed like a rather pleasant place to live. The temperature was a sunny 70o F the entire time I was there, tropical seas sparkled everywhere you look, and the people were unceasingly polite. Prices were astonishingly cheap; maybe inflation hadn’t gotten there yet. You do need to learn to think in yen, which can take some time getting used to. When I visited, the dollar was hovering at around 150 yen, and I’d regularly see prices like ¥2,000, which translates into about $13.

I spent a night in Naha, in a grand, ten-floor hotel with a five-star rating. It cost $47 per night. The receptionist confirmed my reservation with a lot of bowing, propriety, and politeness. There was an actual key — metal, with teeth and all, not a card — for the room door, which she handed me with two hands, a sign of respect.

Walking the streets, I was surprised. I’d kind of expected Japan to be a haven of Toyotas and Hondas — even more than Lakewood (the Sienna/Camry capital of the world). After all, these were all Japanese cars, right? But I didn’t recognize any of the cars here. Some were made by Toyota, but they were unlike any I’d seen anywhere else.

Many of them were ancient, or at least they looked that way. The cargo van I was provided with appeared to have come from the 1970s. There were some newer-looking vehicles, but they were all square and boxy and weird. But you’ll love the prices: I caught a lift with someone in a Toyota minivan about the size of a Sienna. He told me he bought it with 10K miles on it for 172,000 yen — about $1,200. Some Americans try to buy cars here and ship them home, but tariffs….

Lingering Scar

Everything on the island certainly looked Japanese to me: the language, its character, and the features and manners of the locals. But native Okinawans don’t quite consider themselves Japanese — their culture is unique and somewhat different from mainland Japan’s, as is the Okinawan language. In fact, the Ryūkyū Empire was an independent island kingdom until 1879, when Japan annexed the island chain and made it a prefecture, exiling Sho Tai, the last Ryukyu king.

But what’s burned deep into the psyche of this place is the Battle of Okinawa during World War II, the epic battle between the US Army and the Japanese. Much of the local history and landscape was destroyed, hundreds of thousands of people died, and the US took control of the island until it returned it to Japan in 1971.

Okinawans consider themselves twice invaded and colonized — once by the Japanese, and then by the Americans. Although US rule has since ended, the American boot still sits heavily on their neck.

All the Okinawans I met spoke softly and respectfully, but I could still pick up on the simmering tension between the them and the gaijin — foreigners, mostly US military —who inhabit the island. There are 32 US military bases on the island, with over 60,000 personnel (including civilian contractors). The bases occupy close to 20 percent of the land on the island, and the locals want it back. Many of the installations are in the heavily populated, flatter southern end of the island, not in the mountainous north. Pollution, crime, and exploitation of locals are frequent complaints against the gaijin presence here. And the Okis aren’t impressed by the economic impact of the bases — they think they could use the land better themselves.

But the Americans aren’t going anywhere soon, determined to hold the strategic position Okinawa gives them. In 2013, China began making noises about challenging Japanese rule over Okinawa, and indicators of the Chinese threat are everywhere. Signs explaining the time from first alerts to missile impacts from China hang in every public building, along with clearly marked shelters and explanations of defensive procedures. The base here takes its role as America’s first line of defense against China very seriously.

A Yid Bleibt a Yid

Because many of the Jews I’d come to support are part of the US military, our events were hosted by Kadena Air Base, a US Air Force installation in the southern third of the island. The vast US military presence here brings a mix of foreigners, among them a number of wandering Jews. Isolated from the rest of world Jewry, they’ve pulled together to form a kehillah.

Ben Craig, a US Marine, is the picture of a committed Jew. At the time of my visit, he was the de facto president of the kehillah, leading davening, acting as the point man for community events and Yom Tov services, and always eager to arrange Torah classes. He wore his black yarmulke proudly, though it did seem incongruous with the tattoos on his left arm.

Ben shared some of his history with me, telling me that five years ago he was the farthest thing from an observant Jew one could imagine. “I knew more about Judaism from Netflix than from my own experience,” he said. His journey back to Torah took an interesting, winding path; significant signposts were the Marines, Okinawa, and COVID-19.

Stationed at Camp Foster, Okinawa, during 2020, locked in place by the virus that originated on the continent 500 miles west, Ben felt a yearning for something to connect him to home — and beyond, something deeper. He found his unit chaplain and asked for a Jewish rabbi, eventually meeting US Air Force Chaplain, Captain Levy Pekar at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa.

It was at Kadena’s Chapel Two that Ben experienced his first davening, a Lecha Dodi Shabbos service that whet his appetite for connection to the Divine. Walking home with Pekar and his family, they engaged in a conversation that would be the first of many and ultimately changed his life.

“I learned the foundations of what it meant to be a Jew, what it meant to put one’s service towards G-d, and the story and understanding of my peoplehood,” Ben later wrote in an article he published in the Jewish-American Warrior, a seasonal magazine distributed by the Aleph Institute. His trajectory of learning and observing spiraled upward from there, with highlights such as a belated bar mitzvah on his 27th birthday at a Chabad House in southeast Asia, surrounded by a potpourri of “the myriads of characters one finds in a tiny community thousands of miles from the nearest kosher deli.”

Since my visit, Ben has since been reassigned to the Silver Spring area, where he married and continues to lead a committed frum life. “I grew up with Chanukah being something we celebrated so that we wouldn’t feel left out,” Ben says. “Now, even Yom Kippur is one of my favorite holidays. Its moments of deep introspection, repentance, and hope for the future bring out a sense I have been unable to replicate anywhere else.”

Chaplain Pekar led the Okinawa community for three years, but has since been reassigned to Ramstein Air Base in Germany. During the time I spent there in Okinawa, no active-duty Jewish chaplain was present.

I caught up with Pekar later. He’s a dynamic and charismatic leader, who told me he thoroughly enjoyed every moment of his tour at Okinawa, although he dubbed it with the Israeli expression, “Sof ha’olam, smolah — [Go to the] end of the world, make a left.” He took no credit for Ben’s return, attributing it all to the young man’s personal drive.

He said his time at Kadena was liberally sprinkled with many adventures and rewarding experiences, as well as difficulties navigating frum life so far from community. “At one point, we had no kosher meat for nearly a year,” he told me. “We had a seder with seventy people, and served fish.” As a Chabadnik with no mikveh within a two-hour plane ride, he discovered new uses for the East China Sea.

The Pekars made a shidduch between two Jewish air personnel, both of whom were despondent at having been assigned to Okinawa because they thought they had no hope of finding a marriageable Jewish partner on the island. Neither were religious at the time, but the chassan has since returned to observance and transferred from security forces to chaplaincy, while the kallah, a pilot, is on the way.

Surprisingly, the Pekars said they found they had a lot in common with the Okinawans. “They are much closer to us in so many ways than your average American,” Levi explained. “They have a sense of… what we would call among ourselves eidelkeit, tzniyus, and erlichkeit in thought, dress, speech, and deed that is easier to be around.”

By now, the post at Kadena has been filled by Chaplain, 1st Lt. Chaim Roome, but it remains on the Pekars’ minds. “I have this unlikely fantasy,” Levi muses. “One day, when I retire from the military, I’ll return to Okinawa and open the first Chabad House here.”

Hokey Pokey in Oki

I had a packed schedule, but I did want to take a little time to get to know the island. Getting around was a bit of a challenge: This was my first time driving in a country that keeps left (don’t laugh at me, UKers). Actually, the driving part was pretty straightforward; you just had to think twice at every intersection, making sure you knew where cars are coming from or into which lane you needed to turn.

It was the turn signal that got to me.

The turn signal and windshield wipers levers were the reverse of what I was used to. So every time I intended to turn, I unthinkingly pushed the left lever, turning the wipers on. In the Okinawa sunshine, this was odd. Locals call the flapping wipers on the vehicles of newly arrived Americans the “Okinawa wave.”

I know when it’s time to concede defeat. Unlike myself, Ben Craig was used to driving on the left side of the road, navigating the narrow highways, and maneuvering the creaky cars of this region, so I wisely recruited him for some exploring.

Our first stop was Shuri Castle, the home of Sho Tai until he was exiled. In general, there are palaces, shrines, and ruins from the era of the Ryūkyū Empire all over the island, although many were destroyed in the Battle of Okinawa.

The palace was obviously once grand and ornate, rising high above the crowded streets around it with spectacular views of the oceans. Its many outbuildings sprawl across stone-paved pathways winding up a hillside. The grounds are bordered by Asian trees draped with thick, droopy vines that are common here, and there are shrines to some pagan beliefs on site. Tourists and locals were visiting, and like everything else in Okinawa, the entrance fee, charged in yen, converted to pennies.

A large portion of the grounds was encased in a large, three-story glass enclosure. While we couldn’t enter, we climbed to the top of a nearby temporary platform to see what was going on inside. It spoke volumes of the people who live on this land.

In 2019, a fire gutted the buildings, which are made completely of wood. Now, hordes of Japanese craftsmen were hard at work in this glassed-off area, rebuilding the palace exactly as it was, down to the inch — actually, down to the millimeter. The building was being crafted of wood with no nails or fasteners. The beams and planks were measured and cut precisely to fit together like a 3-D jigsaw puzzle, serrated ends locking together to hold up a massive structure. The workers were cutting, sawing, sanding, and planning with a precision that can only be found in the Far East.

Moving on from Shuri Palace, there’s one spot I particularly don’t want to miss. It’s a key site of World War II which Okinawans call Maeda Escarpment; Americans call it Hacksaw Ridge.

Hacksaw is in the city of Urasoe, named for the ancient Urasoe castle built on its slopes. We drove from Shuri Castle to the nondescript hill, which seemed oddly neglected. In most countries, a famous war site would be heavily developed, with museums, reenactments, tourist attractions, souvenir shops… something.

Here, there wasn’t even a road sign identifying the famous battleground. The local municipality seemed far more interested in marketing the Urasoe castle, with explainer signs, walking paths, and picnic tables serving the ruin.

Not a word about Hacksaw.

We climbed to the top from the more gently graded southern side (the north — from whence the Americans attacked is a steep cliff). The actual cliff they scaled is difficult to find today — it looks nothing like it does in war pictures. Eighty years of tree and underbrush growth obscure the edge. When we eventually found it, there was a little sign marking the spot, paying desultory homage to Doss and the battle (see sidebar). I was shocked there wasn’t more to commemorate the event.

We descended the hill on the walking path that crosses the mountain in hairpin turns. The hillside is pockmarked with old cave openings, and signs in Japanese warn visitors not to enter because of the risk of collapse. Several loops below the peak, we came upon a massive stone monument, inscribed in Japanese. Google Translate told us that was in memory of the tens of thousands of Japanese troops who died defending the hilltop.

In a flash, I suddenly realized why the Japanese wouldn’t celebrate Hacksaw — it was a loss for them. Unlike today’s Germans, who do their best to distance themselves from their Nazi past, the Japanese are still fiercely proud of their fighting forces in World War II, and they are the ones memorialized on this spot.

The Battle of Okinawa and Hacksaw Ridge

Much of Okinawa’s current personality is heavily influenced by 82 fateful days in the spring of 1945, when US forces’ relentless march across the Pacific toward the Japanese home islands came to a bloody climax in the Battle of Okinawa. Admiral Chester Nimitz, in charge of the campaign, saw Okinawa and its flatter southern lands, including the airfield at Kadena, as vital for staging the inevitable final assault on Japan, and was determined to take it at all costs.

Navy ships flooded the Okinawan harbor, and the US Tenth Army was formed especially for the campaign. The mixed unit, comprised of Army and Marines infantry, landed on the mid-island beaches of Chatan and moved south. Japanese forces, knowing that the key prize was the flat southern part of the island, retreated to that area and set up deeply entrenched defenses, headquartered in Shuri Castle.

Two steep ridges rise in the middle of the southern region: Maeda and Kakazu escarpments. These hills tower over the narrow girth of the island at this juncture, making it impossible for American forces to pass without taking them.

The only way to capture Maeda was to scale the steep northern ridge. Time and again, the Tenth Army fought their way to the top, only to be thrown back and off by a renewed Japanese offensive. They nicknamed the bloody ridgeline Hacksaw.

In one legendary moment, as the Americans regrouped at the bottom of the escarpment, with dozens wounded and left behind at the top, Navy ships in the harbor rained a punishing hail of fire and artillery on the hilltop. One US Army medic, a conscientious objector named Desmond Doss, stayed on the hill. Dodging Navy shells, he singlehandedly patched up wounded soldiers, carried them to the cliff edge, and lowered them down in a makeshift sling. Doss saved over 70 men and was later awarded a Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration. The story has been immortalized in American culture by a Hollywood production.

Almost every Japanese soldier fought to the death. The US forces eventually won the battle and captured the island, after the Japanese commander, rather than surrender, committed hara-kiri.

The costs of the Battle of Okinawa were horrific: over 12,500 US troops (more than four times the number of people whopeople died on 9/11) were killed in the battle, with estimates of as many as 119,000 Japanese soldiers killed. Okinawan civilians suffered most of all, with 149,425 killed or missing. The horror and intensity of the battle, and steadfast refusal of Japanese soldiers to surrender, gave US military leaders pause in their planning to invade Japan’s home islands, ultimately leading to the decision to drop nuclear bombs on it instead.

Okinawa Cholent

Back at Kadena after our little tour, the Jewish community gathered and we began planning for Purim in earnest. We organized a minyan and seudos for the upcoming Shabbos, as well. I would have to make cholent, which was no problem — I bought a large crock pot in a local store for $15 (Japan uses the same electric supply and plugs as the US) and toiveled it in the East China Sea.

Most of the Jews in Okinawa are members or contractors for the US military. I met Jillian Harris, a civilian working for the Department of Defense and a dedicated Jew. She was also key in arranging classes and minyan, and attended each with great vigor. I met a few more marines, and two Air Force special forces MC-130 pilots with very Jewish names. I missed a Belzer chassid doubling as an Air Force JAG (lawyer), who had gone to the continental US to represent the government at a court-martial.

Of course, there were Israelis wherever you go. Avivit was raising Israeli children here, as were a Jewish Navy nurse and her Israeli husband.

We had a nice minyan for Kabbalas Shabbos, and davened using Jewish Welfare Board siddurim donated by the Aleph Institute. Not everyone present defined as strictly Orthodox, but this cholent of Jews all got along — when you’re surrounded by strangeness, you find commonality.

I also met Wei-Wei, a fiercely stalwart Chinese-Jewish woman, who was constantly pushing for only Orthodox standards in all Jewish events and services; she has zero tolerance for Reform and Conservative. She arrived at Judaism when she discovered, through her own research, that she was descended from the Jewish community of Kaifeng, China.

Jews arrived in Kaifeng about a thousand years ago (the exact century is a subject of debate among historians). They were likely Bukharan Jews following the trade routes through Muslim countries to Far Eastern trading partners, and found themselves settling in China. It is unclear whether they arrived over land via Silk Road routes, or by sea, through port cities like Guangzhou or Quanzhou, and then migrated inland to Kaifeng.

The community thrived and maintained its Jewish identity for several hundred years, but by the first half of the 19th century, assimilation, acculturation, and intermarriage had taken their toll and the community began to fade. Records show that by 1849, Kaifeng Jews had distinctly Chinese features. The community effectively ended when it was dispersed during the Taiping Rebellion in the 1850s, and their central shul was dismantled. There was a brief revival after the rebellion, and an attempt to restore the community with financial aid from a Jewish community in Shanghai at the time; but it was too little, too late.

Some interest in identifying the descendants of the Kaifeng Jews was sparked in the mid-1980’s, and several people underwent giyur and began keeping mitzvos. China’s latest census counted about 100 families with Jewish identity traced to Kaifeng, and about 500 people. An organization called Shavei Israel has sponsored 19 returnees to Israel from the Kaifeng Jewish community over the past 20 years, though all were required to undergo conversion.

The Marines Make a Mentch

Another deeply committed Jew with a surprising story was Justin (Aryeh Leib) Rapp. Like Ben, he also found Torah and observance through the Marines, but his story has a different twist.

I met Justin in the parking lot of Kadena’s Chapel Two the day I arrived. He came early for our first shiur. Always a bit of a goofball, he cracked two jokes before we got in the door.

Once inside and ready to learn, though, Justin was all seriousness. He took charge of setting up, getting the food — and displayed a legendary Marine appetite for candy.

Justin was raised in a religious Modern Orthodox family in Long Island, New York, and attended religious Jewish schools throughout his childhood. He volunteered for the Marines while still a junior in high school, enlisted and in-processed in 12th grade, graduated early, and left midway through the year to start basic training.

His rebbeim at Hebrew Academy of Nassau County (HANC) did not take kindly to the Marines as a post-yeshivah program for a nice Jewish boy. They applied heavy pressure on him to go to Israel for a year. “I was told I had to go, or nothing would become of me,” Justin recalled. “They said I wouldn’t be frum if I didn’t go to Israel. But they didn’t realize I wasn’t frum already. I wanted nothing more than to get as far away from my religion and people as possible.”

Once out of school, he dropped all aspects of frum life. But ironically, the Marines brought him closer, not farther, he admitted sheepishly.

“I was a wild kid, with no discipline or sense of responsibility. If I had gone to Israel that year, I would have been partying all night, like half my friends. There was no way I was flipping out,” he explained. “But the Marine Corps gave me maturity, discipline, responsibility, and bearing. It made me into an adult. And I found my way back.”

For all this talk of maturity, sitting with Justin and the small close-knit group of Jews around the table in Okinawa, he still stands out as the class clown. But there was a mettle underneath that you don’t find among non-Marines.

It may have been a search for Jewish community, or an expression of newfound maturity, but while at the School of Infantry in North Carolina, he got the Corps to transport him out of the field to services for Rosh Hashanah and Succos. For Yom Kippur, he pushed for a special Orthodox service with other service members. When he was transferred to Marine Barracks Washington, he was already going to shul, attending tefillos at University of Maryland, Chabad, and a local shul.

At first, he was driving on Shabbos to get to shul. But students at the university offered him a place to sleep and Shabbos meals, so he resuscitated his Shabbos observance. Later, assigned to machine gunnery training at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, he got deeply involved with Chabad of Wilmington, began keeping kosher again, and was soon appointed Jewish Lay Leader. Shortly thereafter, he was deployed to Marine Camp Hansen in Okinawa, which is where I found him.

Ben left Okinawa a few weeks after my visit, and Justin took over, leading services in the strictly Orthodox tradition, saying the weekly devar Torah, and, in his words: “Dragging as many Jews as I can find to shul.”

Venom in Aisle 3

Local Okinawans may have been surprised by cholent, but you should see what they are willing to imbibe.

Finding some shade under a copse of trees outside Shuri Palace, we stumbled on a warning sign featuring a fanged serpent announcing the presence of a unique Okinawan menace: the habu snake. This reptile is found only in Okinawa, and its venom packs a wallop. A bite is not instantly deadly, but is enormously painful. The venom spreads through the blood system, killing red blood cells and destroying other parts of the blood. There is an antivenom, but doctors are hesitant to use it because of its own severe side effects.

A local shared a legend with me that claims that once bitten by the habu, a person is banned from Okinawa forever, because the antivenom only works once. For his own safety, he must leave the island and its indigenous venomous reptile and never return. A quick fact-check didn’t support this theory, but I did note that a second application of the antivenom increases the side effects and becomes increasingly uncomfortable, while the venom is more effective.

I prefer not to risk it.

For now, I noted with relief, there were no habu lurking in the tall grass.

We visited Okinawa’s main mall so I could look for some trinkets for the kids. I ended up selecting, among other things, a Japanese version of chess that is too complicated to figure out — it involves multiple directions of play, new pieces, captured pieces coming back to life, and a host of other quirks somewhat typical of this culture. Of course, I couldn’t leave without some Samurai swords….

“Come, I’ve got to show you something,” my guide said with a twinkle in his eye. We maneuvered through the aisles to the whiskey section, where he pulled a bottle of firewater off the shelf. Inside, staring at me with its fangs bared from the bottom of the amber liquid, was a habu.

Apparently, the locals thought it would be cool to make an alcoholic drink out of venom. The result was habushu, a drink made by drowning a live habu in fermented rice gin, and allowing it to age in the alcohol. Supposedly, the venom seeps from the snake’s body into the whiskey, adding a real fireball flavor. The alcohol officially neutralizes the poison, but drinking it does shock one’s liver and cause it to stop functioning for about half an hour. This adds to the fun, because any alcohol drunk during that time is not processed, and the drinker doesn’t feel the kick until after the time passes (when I guess he gets it all at once?)

All I could think was “Shelo asani goy.” Or gaijin.

Israeli Ingenuity

One Jewish resident of the island lived too far away to join our events, but I sought him out later. Professor Gil Granot-Meyer, a prominent member of the faculty leadership at the Okinawa institute of Science and Technology (OIST), lives near OIST in the narrowest belt of land in the central part of the island. Okinawa is only two miles wide here, and his daily routine takes him through its mountainous, treelined terrain, with the blue oceans never more than a mile away. The campus itself is uniquely beautiful, with creatively designed interiors and carefully landscaped grounds. It seems to be the pride and joy of Okinawa.

Gil was recruited to OIST when he stepped down from a prestigious position at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rechovot. He signed up for what he thought was an advisory position as a vice president, but discovered they were looking for a leader. He moved his family to Okinawa, and has been enjoying the experience of living there — but also feels intense longing for his home country and land. Three of his children returned to Israel after October 7; two are serving in IDF intelligence directorates, while a third is finishing high school.

Gil’s expertise is at the nexus of science and business, turning discoveries into products and startups that can make money and help people. “I strongly believe that science has the potential to improve our lives,” he said, “but most universities fail in that. They produce knowledge, not technology. They publish it and that’s it.” His specialty is “turning lab results into products and services.”

Weizmann and OIST are two-of-a-kind universities — ones that focus on research, not education; prioritize fluid sharing, not departmental structure; and use lots of government funding. They are at the forefront of the new age of “interdisciplinary” research and education.

Gil’s cell phone rang while we were talking. It was his wife, and they talked in rapid Hebrew, belying a longing for their home country. “[Okinawa] is far from everything,” Gil admitted. Since October 7, he’s struggled acutely with being so far from Israel. “We’re torn between our mission here and the value we bring, and the needs of our family and country,” he said. “The university is very understanding of our situation, and I’m authorized to go home four times per year.” Gil makes full use of his four trips per year, going home to be with family and country in trying times.

When I asked him what reactions October 7 have brought in its wake, he told me he hadn’t seen the virulent antisemitism prevalent on American campuses. “Japan is very mild in its reactions. We don’t see big demonstrations. The Okinawans are very warm — we get a lot of support from them. There is some pro-Palestinian noise from student groups, but it’s mostly very calm and respectful. The university wants to be neutral and international.”

Okinawa’s history plays into its reactions to the warring in the Middle East. “This land is deeply scarred, and still hurting from the war here,” Gil explained. “They are very pacifistic and anti-war. They experienced war very severely, and were very warm in their support after October 7.”

Immediately following Hamas’s attack, demonstrations in support of Israel were held on the beach in Okinawa City. But that doesn’t mean the island is without its haters. Walking the streets of the city several months later, I spotted some “Free Palestine” and “From the River” signs in storefronts.

OIST is almost fully funded by the Japanese government, but its student and faculty bodies are 70 percent foreigners, not Japanese or Okinawans. Its operations are all conducted in English. There are no specialties or departments. Instead, the faculty are just experts in their fields brought together by the university leadership and allowed to work on whatever they want. The university gives them almost full independence to conduct their research.

There are a handful of Israeli students studying at the university, including some post-IDF and some doctoral students. Gil has relationships with them, but as one of the top four in the university leadership, he has to make sure to keep his positions neutral and not air his own views.

Among the new products Gil is working on bringing to market is a type of digitally printed scaffold that can be implanted in patients recovering from spinal cord injuries, allowing them to regrow neurons; a new low-carb strain of rice; a protocol for treating and managing behavior of children with ADHD; buoys that can track and predict typhoons; and technology that can decompose environmentally dangerous chemicals called polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs).

Elixir of Life?

When hailing a cab in Okinawa (or anywhere in Japan) don’t touch the door. Even the tiniest coupe here is fitted with a device that the driver can use to pop the door open for you when he pulls over.

Seeing as the average taxi driver appears to be older than time, this little feature must be adding years to his life.

There is one international crown that Okinawa can boast: It has the longest life expectancy of any place on the planet. People here are healthier and live longer than anywhere else.

Judging by the taxi drivers, they also work longer than anywhere else.

I traveled light — my backpack scarcely weighed 15 pounds — but the driver who jumped out of his seat to load my luggage into his trunk moaned and groaned like it was heavy enough for a weightlifting competition. He finally slammed the trunk shut, and we were off. The car seemed to have been in the family as long as its driver, and it, too, moaned and groaned its way into traffic.

Okinawa is one of only five “Blue Zones” in the world — places with exceptionally long-life expectancy. There are 68 centenarians per 100,000 people on the island, more than anywhere else. Average life expectancy hovers around 90 years.

What’s the secret to Okinawans’ arichus shanim? Scientists having been working on this mystery for a while, without definite answers. Gil Granot-Meyer has a team at OIST studying the riddle, while he works on developing vitamins to bring to market to capitalize on the phenomena.

The most obvious feature of Okinawan life to look at for longevity is nutrition. Locals have a unique diet — but it’s not what you would expect. “Okinawans eat primarily high-carb starches and rice,” Gil explained. They also eat a lot of fish. “But the secret might be a special breed of lemon, the shikuwasa, that is found here, that has a lot of antioxidants and health benefits.”

Actually, over the last ten years or so, Okinawa’s life expectancy has been slipping, and it may have lost the top spot. Most researchers blame the Americans for this- as local shops and markets adapt to reflect the appetite of American service members, they have introduced classic American high fat and fried foods, which is killing off the Japanese.

Interestingly, some researchers credit the local health to what they call the “Okinawa 80 percent rule,” which states that a person should only eat until he is 80 percent full. This is remarkably close (lehavdil) to the Rambam’s dictum (Deos 4:2) to eat only until three quarters satiety, or 75 percent.

When Zeidy Was in Japan

We had a great Purim amid the hustle and bustle of Okinawa and Kadena Air Base. While the gaijin and Okinawans went about their business, we read the megillah and celebrated a uniquely Jewish victory, vast oceans and many time zones away from our Jewish roots and families. But the megillah spoke to us much the same.

Organizations that support Jewish members of the US military, such as Kosher Troops and Jewish Soldiers Project, sent care packages, mishloach manos, and endless hamantaschen and groggers. We had a festive seudah, and shared Torah and inspiration.

Back home, my kids dressed up in traditional Japanese costumes.

I stayed another week, and we packed in as much Torah as we could. Soon, it was time to go, but not before I would get a mysterious wink from Shamayim.

One morning, passing Chapel One, I noticed tables laden with books. Ever a bibliophile, I stopped by to look for anything interesting. The Catholic community had cleared out their library and were giving everything away. Most of the books were marriage, relationship, and self-help tomes, all written from a heavily Christian perspective.

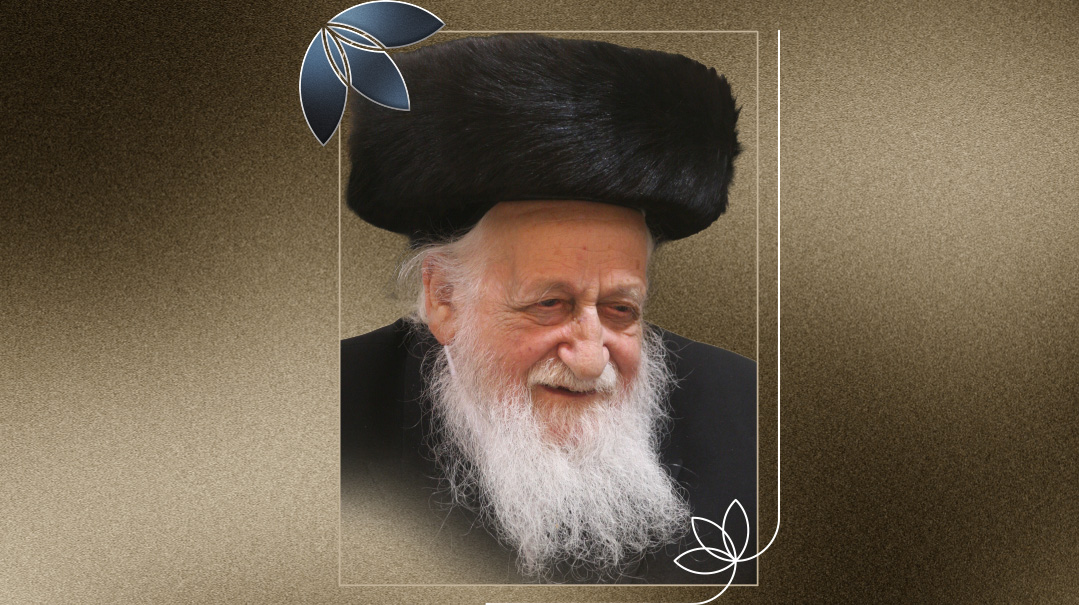

But atop one pile sat a thin green volume with an unmistakably Jewish bearded face on the cover. Titled Operation Torah Rescue, it featured Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz and Rav Chatzkel Levenstein on the cover, against a backdrop of the famous Bais Aharon shul in Shanghai.

Wondering how the book got here, I picked it up and flipped it open — right to a picture I had seen before in a family album. It was my grandfather, Rav Avraham Tzvi Landa, one of a number of chassidish bochurim who had escaped from Vilna to Shanghai together with the Mir Yeshiva on its flight across Europe and Asia. He was a talmid at Tomchei Temimim and snagged one of the last visas tossed out the train window by Sugihara, the Japanese consul, as it pulled out of the Vilnius Station.

The picture, of unknown origin, showed a group of bochurim arriving in Kobe, Japan, clutching all their worldly possessions. It was found by Rabbi Marvin Tokayer during his extensive research on the Japanese rescue of Jews during the Holocaust, chronicled in his book The Fugu Plan (fugu, like habu, is a highly poisonous fish that the Japanese convert into a delicacy). In another curious coincidence, Rabbi Tokayer was a US Air Force chaplain who served in Japan, later returning to the country to serve as a civilian rabbi for the Jewish community of Tokyo for 18 years. He later founded a shul — which he still leads — in Great Neck, New York. Among his many accomplishments, Rabbi Tokayer wrote no less than 20 Torah books in Japanese.

Front and center in the photo was my grandfather, who had passed away five years earlier at the age of 100.

His time in Kobe was legendary in our family. Stuck in on the remote Japanese island over Yom Kippur, Rav Avraham Tzvi was faced with the quandary of when to keep Yom Kippur. The locale falls into the zone of machlokes regarding the international dateline.

Ever a man of intense discipline and yiras Shamayim, with no clear psak, he fasted two days. The incident was on my mind as I prepared to travel to Okinawa and consulted a posek regarding what to do about Shabbos. The response was to keep issurei melachah d’Oraysa on Sunday.

My Zeidy was ever grateful to the Japanese for the role they played in saving his life during the Holocaust. He never went back, but 85 years later, here I was, coming full circle, meeting his image in the land of the rising sun.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1099)

Oops! We could not locate your form.