A Light to the World

Rav Binyamin Elyashiv shares the charms and challenges of growing up in the shadow of the gadol hador. A special conversation on Rav Elyashiv’s tenth yahrtzeit

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Family archives

The most startling thing about sitting together with Rav Binyamin Elyashiv, third son of Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv ztz”l, is the visage.

In the living room of this small apartment in Jerusalem’s Shikun Chabad neighborhood, I’m transported back to my youth, to those special occasions when I’d have the privilege of sitting in the presence of Rav Elyashiv in the tiny room on Rechov Chanan in Meah Shearim. If you closed your eyes, you could think for a second it’s Rav Elyashiv — whose tenth yahrtzeit is 28 Tammuz — talking to you now.

Rav Binyamin is an astonishing lookalike — from the penetrating eyes to the chiseled cheeks and beard, and even to the soft, mellifluous voice. He gets this all the time, yet what can one expect, when even his living standards are similar to the home he grew up in? While the apartment on Rechov Chana, where he lives with Rebbetzin Leah, a daughter of Rav Michel Yehudah Lefkowitz ztz”l, was probably built at least 70 years after that of his parents, the material standards echo the same theme: that life is so much more than creature comforts. There’s a tiny kitchen that can barely contain two people at once, a funtional living room with a practical table surrounded by shelves and shelves of books… and an old telephone.

Sitting here somehow brings me back: As a child growing up in Meah Shearim, it was common to find myself in the dilapidated Tiferes Bochurim shul, and later in the caravan that replaced it in recent years. If I was able, I would be there for Havdalah on Motzaei Shabbos. Rav Elyashiv would hold the pedestal kos, make Havdalah while sitting down, and recite the Ribbon Kol Ha’Olamim tefillah quietly while the crowd sang it with a special niggun. While everyone else was enjoying the elevated atmosphere, Rav Elyashiv would begin to look impatient: For him, it was time to get back to his Gemara.

A decade has passed, and meanwhile a new generation of children has emerged who never knew Rav Elyashiv or what it meant to have someone like that in Am Yisrael’s midst. I’m here with Rav Binyamin in order to fill in the gaps.

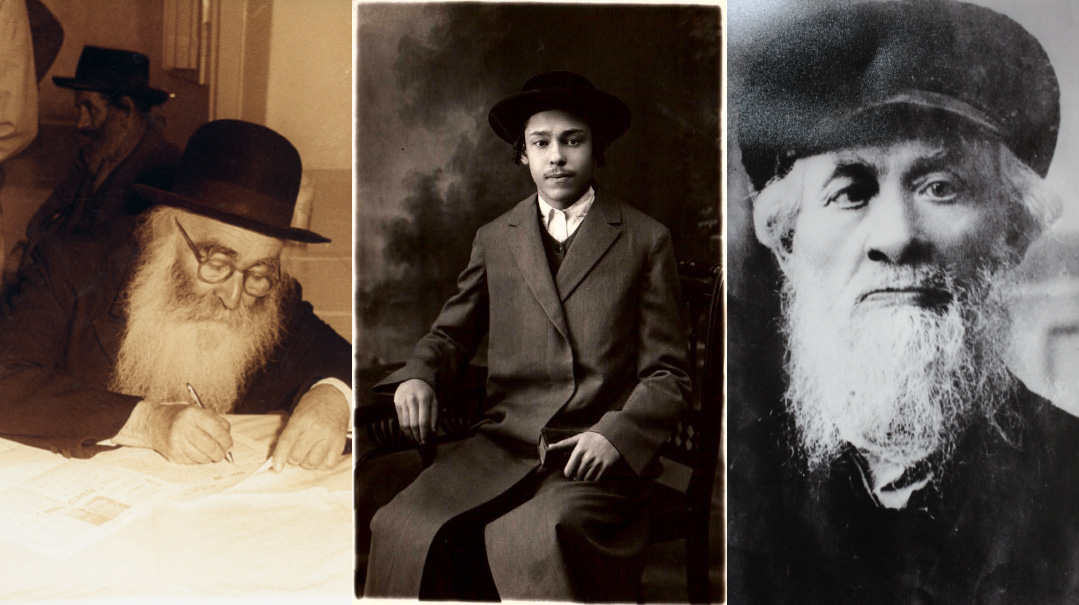

A young Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv (middle), his grandfather the Baal HaLeshem (right), and his father-in-law Rav Aryeh Levin (left). All he wanted was to sit in a corner of the shul and learn

“A

ll his life there was one story, the story of Torah,” says Rav Binyamin, although he admits that for him and his 11 siblings, it wasn’t always a normative childhood. “Sometimes there was literally nothing to eat, and there were times when we went to bed hungry — but we wouldn’t feel it that much, because we’d gotten used to it, and we all knew we were on the same team.”

Poverty, though, was just one piece of a much larger picture that begins in the town of Chavel, Lithuania. Rav Avraham (Erener) and Rebbetzin Chaya Musha — daughter of the famed kabbalist Rav Shlomo Elyashiv, known as the Baal HaLeshem — had already been married for 17 years without children.

In those days, it was common to do laundry one day a week. On Laundry Day, all the dirty laundry of the week was gathered and washed, a full-day project of soaking, scrubbing, rinsing, and drying. One one washing day, Rebbetzin Chaya Musha hung up the clothes she had worked throughout the day in order for them to dry, when a distraught neighbor was so irritated by the laundry flapping in the courtyard that she cut the clothesline, sending the clean laundry into the thick mud below.

Chaya Musha was silent. She quietly collected the dirty clothes and returned home to rewash them. She didn’t even mention the incident to her husband when he returned from the beis medrash that night. But a few minutes later, there was a pounding at the door. There stood the neighbor, crying that her little son had suddenly fallen ill and was having difficulty breathing, and asking the rebbetzin for forgiveness. Chaya Musha, for her part, forgave her neighbor wholeheartedly, and even gave a brachah to the little boy for a refuah sheleimah.

A year later, in 1910, their only son — Yosef Shalom — was born.

Not far from them lived Rebbezin Chaya Musha’s father, the holy gaon Rav Shlomo Elyashiv — the Baal HaLeshem — who had previously given his daughter the cryptic blessing, “You will have one son, and he will be a light to the world.”

When Yosef Shalom was a year old, Rav Avraham was invited to serve as a rabbi in the town of Gomel in Russia, and so the family moved there from Chavel (although he eventually lived out his years in Eretz Yisrael, he was always known as the Homeler Rav).

Family attention was naturally directed to their only son, Yosef Shalom, who was an extremely gifted yet weak and sickly child. He rarely left the house to socialize with children his age, preferring instead to study with his father, whom he always considered his first rebbi.

The family — the Homeler Rav, Rebbetzin Chaya Musha and her father Rav Shlomo Elyashiv, and 14-year-old Yosef Shalom — immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 1924 and made their home in Jerusalem. The entire family took on the name Elyashiv, so that they could enter Mandatory Palestine under one family “certificate.”

The family lived together in a small house in Meah Shearim, where young Yosef Shalom — who took to studying alone in the corner of the Ohel Sarah shul — was a faithful servant of his holy grandfather, helping him to compile his writings on Kabbalah. Although he never admitted it publicly, it is said that Rav Elyashiv was an expert in Toras Hanistar. (Rav Aharon Leib Steinman ztz”l once testified, “If there is anyone in our generation who knows Kabbalah, it is Maran Harav Yosef Shalom.”)

Yosef Shalom was 16 years old when his grandfather, the Baal HaLeshem, passed away. At the same time, his father established a shul in Meah Shearim called Tiferes Bochurim, a place for hardworking balabatim to learn at night and remain in a Torah framework. Rav Avraham would give shiurim there every day, and occasionally his son would substitute. But that meant that Rav Yosef Shalom would have to present his Torah in a way these simple yet sincere men could understand. Rav Elyashiv continued this balabatim shiur for decades, and it was only in more recent years when it was “discovered” by more learned avreichim that Rav Elyashiv agreed to raise the level.

The year 1929, remembered in the Old Yishuv as the year of terror and pogroms, was actually a time of joy for the Elyashiv family — for it was then, at age 19, that the tzaddik Rav Aryeh Levin (at the suggestion of Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook) chose the quiet, scholarly Yosef Shalom for his daughter, Sheina Chaya. Sheina Chaya, however, was hesitant. She was a bubbly, outgoing young lady, and she told her father she was afraid that this bochur, special talmid chacham that he was, was just too quiet and that she would have no one to talk to after the marriage.

Rav Aryeh was unfazed. “No problem,” he said, “I’ll come over every day to talk.” Rav Aryeh not only fulfilled that promise, but added to it: He was dedicated to the support and upkeep of the home, so that Rav Elyashiv could be totally free to learn.

In the little home they started out in and never bothered renovating, the Elyashivs raised 12 children, five sons and seven daughters (six of them predeceased him and the Rebbetzin, who passed away in 1994): Rav Shlomo a”h; Rebbetzin Batsheva (wife of Rav Chaim Kanievsky) a”h; Rebbetzin Sarah Rachel (wife of Rav Yosef Yisraelson); Rebbetzin Dina Ettel (wife of Rav Elchonon Berlin); Rebbetzin Aliza-Shoshana (wife of Rav Yitzchak Zilberstein) a”h; Rebbetzin Leah (wife of Rav Ezriel Auerbach) a”h; Rebbetzin Gittel (wife of Rav Binyomin Rimmer); Rav Moshe; Rav Binyamin; Rav Avraham a”h; Rivkah a”h — killed as a toddler by Jordanian shelling in 1948; and Yitzchak a”h — who died in infancy.

According to Rav Binyamin, immediately after the sheva brachos, when Rebbetzin Sheina Chaya wanted to coordinate with him in running the affairs of the home, he asked her if he could have some initial time where he wouldn’t be bothered with worldly, practical issues, but could learn Torah diligently without any interruptions. She asked how much time he was talking about, and he answered: “A thousand days. Give me one thousand days to study day and night, without a break, and then I’m all yours.”

The Rebbetzin agreed — and her new husband practically confined himself to the beis medrash for the next three years, creating the song he’d sing for the rest of his life. A thousand days later, it was Rebbetzin Sheina Chaya who wanted to prolong the agreement — she would be thrilled if the song continued for a hundred years.

Once Rav Elyashiv was appointed as a dayan, his brave and compassionate rulings were noticed

T

oday, we all know the song, but back then, with a husband in the beis medrash from morning to night, how did the Rebbetzin manage even a mininum of financial stability, raising a dozen children in the process?

In the beginning, says Rav Binyamin — a mechaber seforim who today runs the kollelim of Tiferes Bochurim — both grandfathers, the Homeler Rav and Rav Aryeh Levin, gave what they could. Later, Rav Elyashiv actually earned a respectable salary upon joining Rav Herzog’s kollel, and then becoming a dayan for the chief rabbinate beis din after receiving a glowing semichah from Rav Zelig Reuven Bengis, gaavad of the Eidah Hachareidis.

The children, however, knew that the priorities weren’t about making money.

“We lived in two rooms,” Rav Binyamin says. “When we were young, we all slept in one of them — our parents and us — and in the second slept our paternal grandparents.”

With such a crowded home and the commensurate noise of small children, Rebbetzin Sheina Chaya knew she’d need to take action if she wanted to keep her husband studying unhindered. When the noise increased, she sent him out to Ohel Sarah, and took care of everything on her own.

Rav Binyamin says he doesn’t even remember his mother sending the kids on errands. For example, he doesn’t remember ever going to the grocery.

“Only our mother went,” he says. “In general, she took care of everything related to the home and the children. There was only one time I remember when she took the unusual step and decided to interrupt Abba — there was a concern that one of the children was having an appendicitis attack, but she didn’t know which direction to take with it. So she walked to the beis medrash, and standing by the window, she heard him, as usual, studying with devotion in his classic sing-song. She decided to go back as she came. In the middle of the way, she again started feeling anxious and returned to the beis medrash… but then she left again. Three times she went back and forth, until in the end she decided that whatever happened and however it played out, she was not going to interfere with Abba’s learning.”

With such hasmadah, was it possible for Rav Elyashiv to be an involved father?

“Well, most of the chinuch he gave us was by example,” Rav Binyamin admits. “I don’t remember him ever disciplining us, and certainly never hitting us. When we saw him, we just knew how to behave. Could there have been a better lesson than that?”

Quality individual time happened on Shabbos between Seudah Shlishis and Maariv, when the house was anyway too dark to learn. Rav Elyashiv would then take a short walk around Meah Shearim, each week taking another child with him and reviewing what the child learned that week.

In fact, it didn’t end when the kids grew up, but carried over to the next generation. Years later, Rav Elyashiv’s grandchildren would come to the house around that time for a farher as well.

Rav Binyamin’s son remembers, “The Zeide would be resting then, and Bubbe would tell me, ‘Go into Zeide and tell him what you learned this week, and he’ll test you.’ I would tell Zeide what Gemara we were learning, and then he’d put his hand on my shoulders and review the entire thing with me by heart.’ ”

The entire apartment wasn’t more than 50 square meters. In later years, the bedroom turned into a “living room” by day and in the middle stood a table, with overflowing bookcases against the walls. In his last years, there was always a grandchild who served as an attendant. While the house was narrow, the ceiling was high, as was customary in ancient Jerusalem to keep the indoor temperature regulated. From floor to ceiling are two walls covered with bookshelves, and Rav Elyashiv knew where every sefer was.

“When Zeide wanted to take a book, he never asked anyone else to bring it,” says Rabbi Aryeh, Rabbi Moshe Elyashiv’s son and Rav Elyashiv’s faithful attendant until the end.

“More than once I would say to him, ‘Zeide, what sefer do you want?’ and he would refuse to say, but instead he would walk up to where it was stacked and take it on his own.”

Between the living room and the entrance foyer is a short corridor, both walls of which are also covered with books, up to the ceiling. An old Amcor fridge also stands there, due to lack of space in the kitchenette.

Rebbetzin Batsheva Kanievsky once teased her husband that his hanhagos were not exactly what she saw in her father’s home: “You know the children, and you can identify each child by name. For us, when we were small children, we weren’t always sure if Abba could do that.”

In the early years, the Homeler Rav would often step into his son’s place regarding domestic affairs, and he would even give the brachah to the children (his grandchildren) on Friday night, while Rav Elyashiv “stole” another page of Gemara.

Until he was 100, Rav Elyashiv was still getting up at 2:30 a.m. to learn. He also continued to give the “simple” shiur to balebatim. It was all the same – it was all about Torah

R

av Binyanim and his siblings grew up in turbulent times — and it wasn’t just in Eretz Yisrael. It was a time of world wars and revolutions, and they were curious as to what their venerated father held on a variety of issues. Didn’t they want to discuss things?

“We might have wanted to, but we never did,” says Rav Binyamin. But it wasn’t just about not disturbing a gadol’s Torah. Fragile as he was, they were concerned for his health.

“He was by nature weak and sickly, and I remember that throughout our childhood we were afraid we’d grow up as orphans.”

During the War of Independence, the Elyashiv family left their home in Meah Shearim, which was on the border, and moved to the Mishkenot neighborhood, into the house of the shver, Rav Aryeh Levin. During that year, the family suffered two crushing blows: The Elyashivs’ youngest daughter Rivkah, just 18 months old, was killed by a Jordanian shell while in the arms of her older sister, Leah. During the same year, they lost an infant son, Yitzchak, who fell ill and died shortly after he was born. But even during these tragedies, as much as he felt the excruciating pain of life’s blows, it didn’t move him from the study bench.

Yet alongside his complete disengagement from the world, he also constantly distanced himself from the possibility of harming another Jew. Rav Binyamin remembers how for many years, a widowed and homeless fellow would join the family for Shabbos meals, and for some reason, he was convinced that he possessed rare cantorial skills.

If anyone made a negative comment about his singing, he would answer back, “Rav Yosef Shalom himself asked me to sing, and you’re complaining?”

During the seudah, he would belt out his off-key repertoire, but despite the suffering of everyone else at the table (including Rav Elyashiv himself, who was known to be extremely musical), Rav Elyashiv instructed his household to respect this Jew and to compliment him on his exceptional singing.

And, of course, becoming a dayan was a reality check as well. He became head of the Beis Din Hagadol in Jerusalem in 1952. At the time, Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog encountered a serious halachic problem of a Yemenite girl who arrived in Israel after having been betrothed by her mother in Yemen to a man who subsequently converted to Islam. In Israel, her status was officially that of an agunah, meaning that she could not marry again. Rav Elyashiv found a way out, ruling that because the girl’s father had not been present and she was too young to agree herself to the marriage — she was perhaps 11, though no one knew her precise age — the marriage was annulled. The ruling was praised by rabbanim of all streams as both daring, lenient, and compassionate.

The other great rabbanim of Eretz Yisrael soon discovered Rav Elyashiv’s great prowess as an arbiter, even though he was younger than most of them. Yet after 22 years of serving on the Jerusalem Beis Din and the Beis Din Hagadol, certain political appointments and decisions pushed him to hang up his robes — and he went back to his corner in Ohel Sarah, where he really wanted to be all along (and he even got a pension).

Rav Elyashiv was what is commonly referred to today as an “autodidact” — his entire acquisition of Torah was self-taught. He never studied in an organized yeshivah or systematically heard shiurim from others (although he did receive guidance for practical halachah by doing shimush with several Jerusalem rabbanim). In a sense, he was his own rav. Rav Binyamin emphasizes, though, that his father never suggested or encouraged others to go that path.

And he also never bothered to write his own seforim.

“True,” says Rav Binyamin. “He told me it was too time-consuming, that he’d rather use the time for learning. But he did authorize files to be printed of his rulings. And he had extensive correspondences. The Steipler would correspond with him regularly, and he would sometimes show the teshuvos to the Chazon Ish, who marveled at his insights and remarked, ‘Whoever does not study Torah for its own sake cannot come up with such logic.’ ”

Yet through all this, Rav Elyashiv continued to give his balabatim shiur to the simple folk, many of whom never even learned in yeshivah.

“Well, he had to — he inherited it from his father,” says Rav Binyamin. “But don’t think it was a shame that he had to drop down so many levels — he learned from his father how to give shiurim to the common people. The Homeler Rav was was a darshan for the masses, not a rosh yeshivah for the elite. The maggid Rav Shalom Shwadron also delivered shiurim in Tiferet Bochurim. After the Zeide passed away, it took my father a while to adjust to the role, because he was the kind of person who wanted to learn every minute, but he had to. And he did it happily — for the rest of his life.

“But that wasn’t in contravention to the fact that until age 100, he was still getting up at 2:30 a.m. to begin his learning day, or that crowds would gather at his door waiting for a ruling, an eitzah or a brachah.”

Yet, did he realize what his status was in the chareidi world?

“What’s the question?” says Rav Binyamin. “Of course he knew.”

Then why did he run away from leadership, and consistently refuse to join the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah?

“Because it wasn’t for him.”

Total Clarity

By Rabbi Ephraim Zalman Galinsky and Rabbi Eliyahu Gut

W

hat is a tank’s status when it comes to the laws of eiruvin? Is an armored vehicle’s hatch considered a doorway for the purposes of lighting the menorah? And can a Mossad recruit violate Torah prohibitions as part of his training?

It was only a posek of Rav Elyashiv’s stature who could be entrusted with questions like these, and it was Rav Avraham Moshe Avidan z”l, a deputy chief rabbi of the IDF, who brought the unusual sh’eilos to the tiny apartment at the edge of Meah Shearim.

Rav Avidan, who became a rosh yeshivah in Shaalvim after two decades in the IDF, gave the following interview shortly after turning 80, before passing away early last year. He got to know Rav Elyashiv long before the latter became famous as the last word in halachah.

Rav Elyashiv was a dayan on the Chief Rabbinate’s beis din, which is separate from the military rabbinate. How did you first come to know him?

“I was looking for a rav to whom I could refer all the different questions that come up in the army,” recalls Rav Avidan. “I tried a number of addresses unsuccessfully before I met Rav Elyashiv and realized that I’d found what I was looking for. This was toward the end of the period when he was a dayan at the Rabbanut beit din, and our friendship continued later.

“We became very close and spent a lot of time together, with meetings lasting as long as two and a half hours. Once we worked through a Rambam on the subject of giyur over the course of two sessions, each over two hours long. I remember that he said about one segment in the Rambam that it belonged in Moreh Nevuchim.”

I once heard a story involving Rav Elyashiv’s psak regarding a tank, and that he had to be shown what a tank was first. How did that happen?

“The story was as follows: When I was the deputy chief rabbi of the IDF and the head of the halachah and beis din branches in the military rabbinate, I had time to learn. As the rabbi of a unit, there was no time to learn — I sat in the base in Neve Yaakov and was busy the whole time.

“But on the general staff, there was time. My chavrusa was my longtime deputy, Rav Shlomo Levanon. We learned Eiruvin together and discussed the precise halachic definitions of a variety of army-related scenarios. There are situations of pikuach nefesh in the army when you can perform any of the melachos, but it’s important to minimize violations, and for this it was necessary to know the din in every case.

“One subject that we discussed was a tank. Which part is considered a makom patur, what’s considered a carmelis, reshus hayachid, and so on, to know what to do if a soldier needed to bring something in or out of the tank on Shabbos, and there was no eiruv.

“This really does happen in times of emergency, when a tank is out in the middle of nowhere and the soldiers simply live in the tank. They eat there, they sleep there, and so on.

“Someone fashioned us a model tank out of plywood. Rav Shlomo Levanon used to go the Steipler and later to his son Rav Chaim and ask him questions about the subjects we had learned. I myself used to request haskamos from Rav Elyashiv for halachic conclusions we reached in the course of our learning. Rav Chaim himself used to send us to Rav Elyashiv, and he would say about certain subjects that we should consult Rav Elyashiv. So that’s how I ended up coming to Rav Elyashiv with the little plywood model.

What impressed you about Rav Elyashiv that made you decide that he was the ultimate address for these complicated halachic issues?

“Many people can tell you about his extraordinary knowledge, but I saw a different angle: He was a uniquely practical person. He amazed me many times over the years because it looked like he had calculated all the different scenarios in advance while learning the sugya and so was able to immediately outline what the halachah was with regard to each section of the tank.

“By the way, we discussed tanks in other contexts as well. For example, about Chanukah lighting, whether a tank has the status of a house. The entrance is from above, so is it considered an aruba, a skylight? By the way, in a standard military tent, which is lower than ten tefachim, one can’t light Chanukah candles, because it’s too low. But you really do live in the tank in times of alert; you eat and sleep there, so it has a din of a bayis.

“I believe he told me that he didn’t know exactly what a tank was, but he certainly knew something. He knew a lot more than we expected. His practical knowledge was really something extraordinary.”

Where else were you able to see that ability to apply halachah to a world far from the beis medrash?

“After I left my position in the army, someone came to ask Rav Levanon a question. Rav Levanon asked me to go with him to Rav Elyashiv. The question concerned an individual who was about to join the Mossad. To qualify, he had to undergo training for how to behave in enemy territory. As part of his training, they wanted him to violate Torah issurim.

“On the ground in a hostile country, it’s pikuach nefesh and presumably permitted, but this was just training — should the man train to eat non-kosher or to violate Shabbos? We didn’t know what to say.

“We went with the individual in question to Rav Elyashiv. He refused to permit it, saying that in the middle of an operation, when it’s pikuach nefesh, he was permitted to do these things, but not during training. What shocked us was that Rav Elyashiv broke down exactly what the Mossad’s needs were, what they were practicing and for what purpose, and following that, what precisely the halachah should be. I asked myself, how does he know so much about the inner workings of the Mossad?

Even though he was always hidden away in the Ohel Sarah shul, sitting and learning…

“That’s because he learned in a way that brought clarity to the finest details.

“Another unique characteristic was his deep sense of responsibility. There were psakim of his that he asked not to make public, because they would sometimes superficially contradict one another. That’s because they were each tailored precisely to the situation of the individual who asked the question.

“I’ll tell you a story from 40 years ago — the details can’t be published, because of that very responsibility. But the gist of it was that a non-religious soldier came to me with a very thorny halachic problem with wide-ranging repercussions — a matter of pikuach nefesh. The soldier’s wife came from a religious background, and she asked her husband to find out the halachah. I told the soldier to ask a certain rav, and I myself would consult Rav Elyashiv.

“The other rabbi permitted and Rav Elyashiv, it turned out, ruled stringently. A few months later, I met the same soldier, and he had found a solution for the problem — he just wanted Rav Elyashiv’s approval. I returned to Rav Elyashiv, and he almost fell out of his chair. ‘Who told him to listen to my opinion? The opinion of other rabbanim who do permit it is not good enough?’

“If I recall correctly, that soldier’s daughter later became observant. I remember these were the words he used: ‘Unzerer a yungerman [an avreich of ours],’ we can ask to be machmir. But what do we want from a simple person?

“I think that explains the contradictory psakim published in Rav Elyashiv’s name over the years. He always took into consideration the unique details of the case in giving his psak, so one can’t really compare two different psakim.”

Rav Elyashiv was busy learning around the clock — when did you bring sh’eilos to him?

“He told me to come on Motzaei Shabbos in the winter, after Havdalah, and then he had time to sit and learn with me.

“I brought two types of questions to him. There were those where I tried to prepare the material in advance, to learn the sugya, but there were subjects that demanded an immediate response, such as in the middle of a war. In the latter case, I myself could see that it was a question but didn’t have time to study the subject in depth. I would go to him at any hour of the day, and he would answer me. He would let me in no matter when I came.

“When I did prepare, I tried to cover every aspect. He would invariably say, ‘Let’s see.’ I once found a teshuvah of the Chacham Tzvi, which I thought would surprise him. No sooner do I began speaking, then he says, ‘s’iz doch da a Chacham Tzvi (but then there’s a Chacham Tzvi).’ Just like that…

“It was mind-blowing. He was what you call in Yiddish ‘frish’ [fresh] in the whole Torah, as if he had just reviewed it. He didn’t neglect a single angle. It was amazing.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 921)

Oops! We could not locate your form.