A Light from Lublin: Rav Meir Shapiro’s Quest to Build Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin

Rav Meir Shapiro dreamed of an institution that would change the definition of what a yeshivah could and should be... A century later, the changes he instituted are alive and thriving

With additional research by Moshe Dembitzer

Photos: Kiddush Hashem Archives, Grodzka Gate - NN Theater (Lublin), Yad Vashem, Ghetto Fighters Museum, Rabbi Avraham Frischman, Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Rabbi Dovid A. Mandelbaum, Walkin Family Machon Meir L'Doros (A. Rotenberg), Piotr Nazaruk, The Museum at Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin, Prof. Moses Schorr Foundation, US Holocaust Museum, Yoeli Hirsch

Rav Meir Shapiro’s name is synonymous with daf yomi, his innovative program for Gemara learning that has Jews across the globe studying the same folio in unison. But he often remarked that he had two “children” — two epic missions that would serve as his eternal imprint in the world. At first glance, it might seem that only the first child — the daf yomi initiative — remains a dominant force in the Torah world. After all, the other child, Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, was dismantled and most of its students were slaughtered by the Nazis.

But in many ways, Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin still exerts influence. Rav Meir’s vision did not encompass the building alone. Despite doubts, outright opposition, and funding pressures that drove him to penury, he dreamed of an institution that would change the definition of what a yeshivah could and should be, and that would elevate the status of lomdei Torah. A century later, the changes he instituted are alive and thriving.

LISTEN to a selection of Rav Meir Shapiros compositions HERE

January 1927

IN a small town outside Philadelphia, a crowd of Jews gathered at a reception held in honor of a visiting Polish rabbi. They were eager to hear the charismatic orator talk of his groundbreaking initiative to construct a massive five-story building in the heart of the Second Polish Republic. More than a mere building, it would serve as a “Central Yeshivah,” an elite institution that would transform the landscape of Torah study in Eastern Europe.

The chairman commenced his introductory remarks, describing the many accomplishments and talents of the dynamic young rabbi from Poland: just months shy of his fourtieth birthday, he was already serving in his third rabbinic position while simultaneously nearing the end of a five-year term as a delegate to the Polish Sejm. The chairman proceeded to introduce Rav Meir Shapiro as the headmaster of a school serving “hundreds of young Jewish girls.”

“I had the urge to correct the record,” Rav Meir recounted several years later to the journalist David Flinker (1897–1978), “but my companion, familiar with American manners and etiquette, whispered in my ear: ‘One mustn’t ever contradict a chairman. His words are considered sacrosanct.’ Left with no alternative, I waited in silence for my turn to speak.”

Rav Meir rose to address the crowd. Building on a theme from a recent parshah, he told of Pharaoh’s daughter rescuing a baby from the Nile, a child who ultimately blossomed into the savior of the Jewish nation. “The scholars and students of Poland are drowning in the floodwaters of misfortune and poverty!” he told the crowd. “If American Jewry won’t reach out and save them, who can say how many potential leaders will be swept away?”

Stepping down from the podium, Rav Meir was certain his passionate exhortation had made an impact. Then he overheard an exchange between a member of the audience and his young son.

“Dad, did the Poles really try to drown that fellow?” the youngster asked, gesturing in the direction of the speaker.

“You heard him,” affirmed his father.

“And he survived?” the son persisted.

“Well, here he is,” replied the man.

“He’s a good fellow,” declared the boy. “Give him a few dollars.”

Today it’s hard to imagine such a dubious reception for the brilliant and accomplished visionary who founded both daf yomi and Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. But back when Rav Meir Shapiro shared his pioneering concept of a yeshivah that provided its students with material stability along with true dignity, he encountered significant and sustained opposition. It took years of fundraising, behind-the-scenes lobbying, and the loss of both his personal savings and health to ensure the stability of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. But the glorious institution that resulted from his perseverance became much more than a yeshivah. It set new, higher standards for the welfare of its own — and, ultimately, all — yeshivah students, permanently elevating their status amid the communities entrusted with the responsibility for their care.

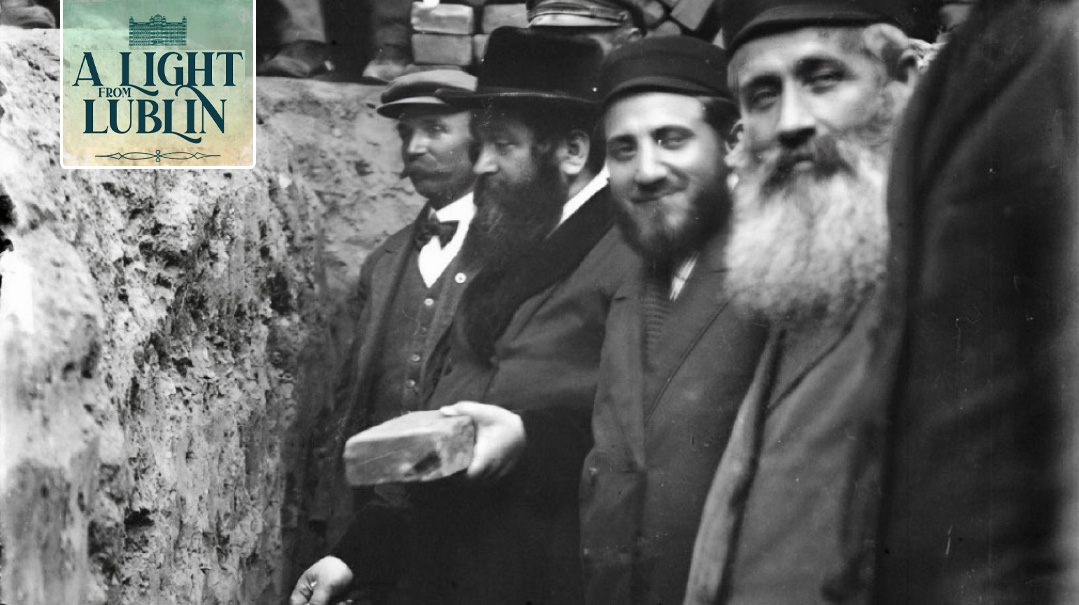

Just a few years earlier, on Lag B’Omer 1924, the old Jewish cemetery of Lublin had pulsated with unusual vitality. A small group of yeshivah students from Piotrkow along with some curious onlookers assembled in the cemetery, their collective gaze fixed upon one magnetic figure.

Amid the ancient gravestones stood the 36-year-old Rav Meir Shapiro, an unusually gifted scholar and rosh yeshivah who had risen to prominence in the preceding years and had recently been appointed rav of Piotrkow. As he faced the gravestones of some of Poland’s greatest Torah scholars, the words he uttered seemed to resonate with the weight of centuries:

“To you great rabbanim, the scholars of Lublin, who spread Torah in this city. You established great yeshivos and nurtured many students… I have come to tell you that I, your servant, Yehuda Meir ben Margala, has decided to restore the crown to its rightful place and I am inviting you to join us in the laying of the cornerstone for this yeshivah, a place where we will raise the honor of Torah until the coming of Mashiach. I am confident that it’s in your merit and in the merit of the Torah that I will succeed in my endeavors for the sake of His great Name and His Torah.”

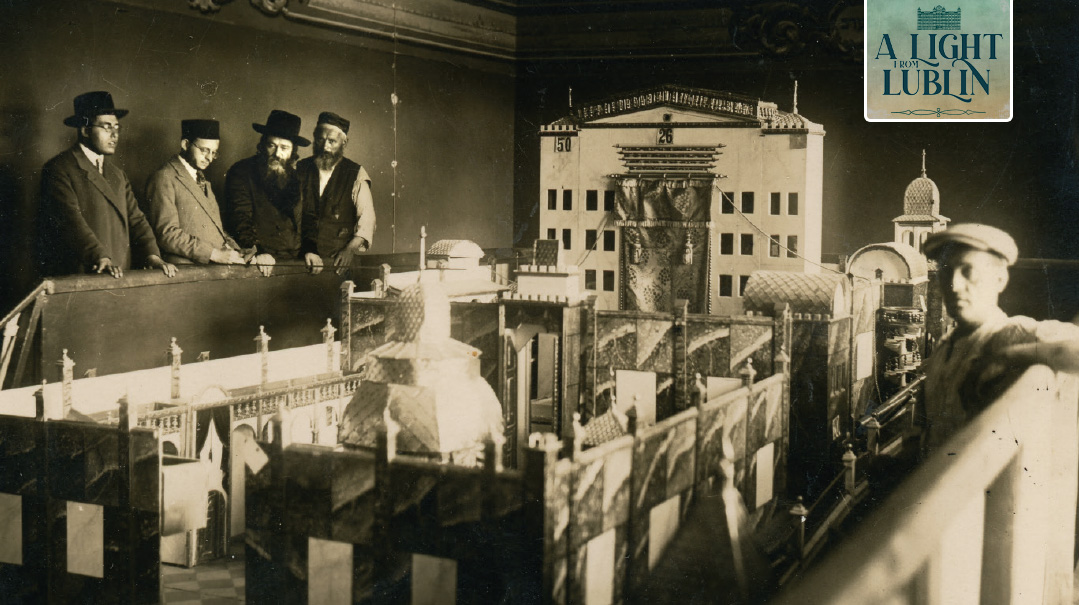

The cornerstone for the most ambitious yeshivah project of its time was laid later that Lag B’Omer day in front of 50,000 onlookers. The new yeshivah was named Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, in acknowledgment of the city’s seminal historic role in the blossoming of Torah study in Poland. Lublin had been host to some of the Jewish nation’s most influential disseminators of Torah — including but not limited to Rav Shalom Shachna, the Maharam of Lublin, the Maharshal, as well as chassidic masters such as the Chozeh, Rav Leibele Eiger, and Rav Tzaddok HaKohein — and Rav Meir hoped his new yeshivah would be a fitting addition to the city’s impressive Torah pedigree.

Flanked by rabbinic and chassidic leaders, Rav Meir addressed the groundbreaking ceremony, where he explained that timing the event for Lag B’Omer was hardly coincidental, for Rabi Shimon bar Yochai had been spurred by the same motive. “Chas v’shalom, Torah will never be forgotten,” Rabi Shimon had declared, citing the pasuk, “Ki lo sishakach mipi zaro.”

The continent had recently emerged from the First World War, which had wreaked havoc upon Eastern Europe, uprooting families and entire communities. The region’s yeshivos were victims as well; many had completely disbanded during the war years. When recovery commenced, the rampant hunger, disease, and homelessness took priority over reinstating Jewish education. (At the previous year’s Knessiah Gedolah, Rav Pesach Pruskin (1879–1939) had bemoaned the fact that among Poland’s three million Jews, there were hardly six or seven thousand yeshivah students.) But a select few chose to act on Rav Shimon’s pledge of “Ki lo sishakach mipi zaro,” and invested prodigious efforts to ensure that Eastern Europe’s Torah learning would be restored to its former glory.

Rav Meir Shapiro was one of those select few. What forged his tenacity and vision?

Rav Yaakov Shimshon Shapiro was named after his ancestor, Rav Yaakov Shimshon of Shepetovka, a close student of the Maggid of Mezeritch, and of Rav Pinchas of Koretz

Chapter I: A Class of His Own

Every Precious Day

Rav Yehuda Meir Shapiro was born on March 3, 1887 (7 Adar 5647), in the town of Suceava (Shatz), Romania. His father, Reb Yaakov Shimshon, was a learned chassid and a descendant of Rav Pinchas of Koretz, one of the prime disciples of the Baal Shem Tov. His mother, Margala (Margalit), was the daughter of the gaon of Monistritch, Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Schor, author of the Minchas Shai and a descendant of the author of Tevuas Shor. His ancestry traced back to Rabbeinu Yosef Bechor Shor of Orleans, one of the Baalei Tosafos. Margala Shapiro also carried a maternal connection to the eminent halachic authorities the Bach and Taz.

During his early studies at the local cheder, young Meir faced significant challenges. At the time, these struggles seemed to destine him for a future as a local laborer’s apprentice. He had a form of dyslexia that made the initial steps of reading a formidable task. But he circumvented this challenge with significant exertion and gained an uncanny ability to recognize words in their entirety, sidestepping the conventional method of piecing together individual letters.

An often overlooked factor in Rav Meir’s growth was the unwavering commitment of his mother, Margala, to his Torah learning. When a private melamed they’d hired named Reb Shalom of Sochatchov was late in arriving after Pesach in 1894, Margala’s distress was palpable. “Do you know, my son,” Rav Meir recalled her saying, “that every day that passes without Torah study is an irreplaceable loss. We offered him [what we thought to be] a very handsome salary, but maybe we offered him too small a sum. Torah is so great and priceless; it may have been too small a sacrifice. Who knows?”

(Rav Avrohom Ausband, rosh yeshivah of Telshe Alumni in Riverdale, has theorized that this emphasis on the indispensability of daily Torah study may have been the driving force that later spurred Rav Meir to initiate the daf yomi program.)

This Reb Shalom was the cornerstone of young Meir’s education for six formative years, and his teachings set Meir on a path to greatness. Sadly, Rav Meir Shapiro’s mother passed away during the turbulent years of World War I, never to see her son’s ascent to prominence in the world of Torah. But the memories of her dedication and sacrifices left an indelible mark on him, as this story, shared by one of Rav Meir’s leading students, Rav Yitzchok Dovid Flekser (1917–1999), later one of the roshei yeshivah at Yeshivah Sfas Emes in Yerushalayim, demonstrates:

“Once, when speaking at a large gathering in Poland, Rav Meir suddenly stated with great emotion, ‘Rejoice and be glad, my mother in Gan Eden, be happy, see the stature and respect accorded to your son, who has grown to become one of the gedolei Yisrael!’ The audience was surprised, not knowing why Rav Meir had praised himself in this fashion, but he immediately turned to the women’s section and called out, “And you, women of Israel, worthy mothers, if you want your sons to become great talmidei chachamim and rabbanim, follow the path of my saintly mother, who sacrificed herself in order to dedicate her son to Torah.”

After advancing beyond the local cheder, young Meir was taken under the wing of his maternal grandfather, Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Schor of Monistritch. This would be a foundational phase in his development. Rav Schor nurtured his grandson’s inherent abilities, also introducing him to the multifaceted environment of communal responsibility. In tandem with his meteoric growth in Torah knowledge, the seeds of his legendary leadership skills were sown.

In 1903, his grandfather suddenly fell ill. During his final days, he drew his grandson close and issued final instructions: “Return to your parents in Shatz. The truth is that I believe you really don’t need me anymore. I hope and trust that you will be able to learn and absorb more Torah than I ever could convey to you.” On the 7th of Adar, as “the Illui of Shatz” turned 16, his grandfather passed away, and the budding Torah giant returned to his hometown.

Rebbetzin Malka Toba Shapiro (bottom left) with family members

Saved By the Shatzer

ITwasn’t only local Torah scholars who welcomed the young scholar back to his hometown. Rabbi David Avraham Mandelbaum — who has devoted his life to furthering the legacy of Rav Meir Shapiro and the story of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin — shared a startling anecdote in his work Igros V’Toldos: Rabbeinu Maharam Shapiro M’Lublin ztz”l.

Upon young Meir’s return to Shatz, enlightened family members attempted to convince him to attend the regional technical school in the Moldavian cultural capital of Jassy (modern-day Iași). Upon hearing of these influences, Rav Shalom Moskowitz, the Shatzer Rav, immediately protested so vociferously that he threatened to lie down in the street and physically obstruct the path of any carriage transporting the town’s prodigy to a secular school.

Rav Meir obeyed the Shatzer Rav and remained under his tutelage. Under the Shatzer’s guidance, he ventured into the esoteric world of Kabbalah, a sphere many deemed too advanced for someone his age. As his understanding and wisdom grew, Meir was empowered to impart knowledge and assisted in laying the foundations of a yeshivah in the quiet town of Shatz, a step that cemented his reputation in the Torah world.

The long list of luminaries who served in the rabbinate in Rav Meir’s hometown of Shatz include Rav Yoel Moskowitz, son-in-law of Rav Meir of Premishlan, his grandson Rav Shalom (the famed Shatzer Rav), Rav Meshulam Roth and Rav Meir’s cousin, Rav Moshe Chaim Lau (pictured here), father of Israel’s former Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau

One Lag B’omer, when he was a mere 17 years old, Rav Meir amazed Rav Yisrael Hager, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz (1860–1936), by delivering an impromptu speech connecting the various statements of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai throughout Shas. Upon meeting him for the first time, Rav Shalom Mordechai Schwadron, the Maharsham (1835–1911), was so impressed that he recited a brachah. Soon enough, an array of renowned Torah scholars ordained him.

Rav Meir’s primary mentor was Rav Yisrael Friedman, the Tchortkover Rebbe (1854–1934). As a Tchortkover chassid (and a lifelong follower of the Rebbe), the Rebbe advised him over the course of his varied roles in communal leadership. Even as Rav Shapiro’s own star ascended, their bond retained its essence: a deep chassid-rebbe connection rooted in mutual respect and reverence for Torah.

In 1907 Rav Meir married Malka Toba, the daughter of Reb Yaakov Dovid Breitman, a prosperous Tarnopol landowner. The young couple shared a mutual vision for Polish Jewry. The financial standing of the Breitman family aided Rav Meir’s ambitions, with Malka Toba staunchly supporting him in each of his endeavors.

Rav Yisrael Hager, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz, was amazed by a 17-year-old Rav Meir Shapiro

Educational Architect

The couple initially settled in Tarnopol, where Rav Meir transformed his father-in-law’s home into a hub of Torah study. In 1910, with the encouragement of the Tchortkover Rebbe, Rav Meir was appointed rav of the Galician town of Galina. Writing in the town’s Yizkor book, a former resident, the journalist Asher Korech (1879–1952), describes Rav Meir’s decade-long rabbinic tenure (which was punctuated by several years in Tarnopol and Lemberg during World War I). For several years Rav Meir refused a salary from the town and referred halachic inquiries to two elder dayanim, Rav Yechezkel Hochberg and Rav Dov Goldberg, enabling them to retain their positions.

Korech writes, “Even when the community council persisted in offering him a salary, Rav Shapiro’s innate magnanimity shone through. He chose to distribute the funds among the impoverished yeshivah students and those ardently dedicated to Torah study. His guiding principle was clear: uphold G-d’s glory and put personal pride aside for the greater good.”

When a member of the community complained that at the age of 23, Rav Meir was perhaps too young for such a position, the young rabbi smiled and responded that every day he would do something about it.

The early years of Yeshiva Bnei Torah in Galina. Rav Meir is seen at center

Korech notes the crowning achievement of Rav Meir in Galina was the establishment of Yeshivah Bnei Torah, which changed the town’s spiritual trajectory:

The landscape of Torah study within our city underwent a seismic shift with the arrival of the esteemed Rav Meir Shapiro. His arrival couldn’t have been timelier, as the town had undergone a palpable decline in Torah dedication among its youth."

A majority had transitioned from traditional Torah study halls to the school established by Baron Hirsch. Consequently, these chambers of Torah wisdom, once bustling with spirited debates and fervent study, now echoed with an eerie silence… The community, although deeply distressed by this evolution, felt powerless to reverse the trend.

However, Rav Shapiro perceived this shift not merely as a challenge but with true, heartfelt sorrow. Possessing an unwavering passion for Torah and an indomitable spirit, he sought to rekindle the city’s once-vibrant Torah spirit. As a testament to his dedication, he instituted the “Bnei Torah society.” With an eye toward the future, he repurposed a centrally-located edifice, tailoring it to serve as a Torah institution, replete with sections spacious enough to accommodate a burgeoning student body.

For the youth, he ensured that the finest educators were appointed, implementing a curriculum he envisioned. Initially, he personally supervised the classes, ensuring the highest standards. Later, this mantle of responsibility was passed on to his advanced yeshivah students, who continued his legacy of vigilance, guaranteeing that educators remained devoted and true to their sacred task.

Under his aegis, the institution thrived, marked by exemplary discipline and fairness. Salaries for educators were punctual, freeing struggling parents from any financial concerns. Students were periodically assessed, with report cards detailing their progress, a testament to the structured approach he championed. Economic standing was never a criterion; both affluent and underprivileged were judged solely by their commitment and prowess in Torah, with the latter group being exempt from tuition fees.

Rav Meir realized early on that the quality of the educational institution depended on the quality of the teachers. When speaking of the importance of having excellent, well-paid teachers of Torah he said, “Look at the difference. When a community hires a shochet, they examine him closely to see if he knows all the laws of shechitah and he is a God-fearing man. And what do they entrust to his hands? An animal! And yet, when they must hire a melamed, to whom they entrust the chinuch of the children, they’re not quite so particular!”

In his early twenties, Rav Meir authored his first sefer, a Torah commentary called Imrei Daas, which linked Talmudic passages to the weekly sedra. Tragically, the manuscript was destroyed during the Russian shelling of Tarnopol during World War I. One page of the sefer, which was salvaged from the blaze, was ultimately buried with him. Also surviving were the haskamos written by some of the greatest gedolim of the time, including the great Galician gaon Rav Meir Arik (1855–1925), the Maharsham, and the aforementioned Vizhnitzer Rebbe, who refers to Rav Meir as “a new vessel containing old wine” who was “learned in all areas of Torah study,” and “a reason to rejoice for there were now new gedolim emerging to take the place of the previous generation.”

The Maharshal’s shul in Lublin (1567-1942)

From Lublin Shall Go Forth Torah

IN

choosing the name and venue of his yeshivah, Rav Meir Shapiro was acknowledging Lublin’s prime location on Poland’s Torah map. For centuries, it served as a city of great scholarship and as home to some of history’s preeminent talmidei chachamim.

Poland’s first great yeshivah was founded in Lublin in 1518 by Rav Shalom Shachna (1495–1558), a student of Rav Yaakov Pollack (1465–1541), considered the pioneer of the pilpul methodology of Talmudic study, and one of the early rabbinical leaders in the old Polish kingdom as German Jews migrated east to Poland during the 15th century. Another student of Rav Yaakov Pollack was Rav Meir Katzenellenbogen (Maharam Padua), who emerged as a leader of Italian Jewry.

Rav Shalom Shachna’s students included his future son-in-law, Rav Moshe Isserles (1530–1572), more commonly known as the Rema; Rav Chaim ben Betzalel (1520–1588), elder brother of the Maharal; and Rav Shlomo Luria (1510–1573), the Maharshal. The Maharshal, whose classic works include Yam Shel Shlomo and Chochmas Shlomo, established a yeshivah in Brisk before assuming the rabbinate in Lublin, a role that also included the stewardship of the local yeshivah.

The Lublin yeshivah was the most prominent one in the entire Polish Kingdom, and there the Maharshal nurtured the next generation of Torah scholars, including Rav Shlomo Ephraim Lunshitz (1550–1619), author of the Kli Yakar and rav in Prague; Rav Yehoshua Falk Katz (1555–1614), author of the Derisha/Perisha and Semah; and Rav Mordechai Yaffe (1530– 1612), author of the Levush.

Later Lublin was home to Rav Meir ben Gedalia (1558–1616), the Maharam of Lublin, whose list of students included the Shelah Hakadosh, Rav Yeshaya Horowitz (1558–1630); and Rav Yehoshua Heschel Charif (1580–1648), author of Meginei Shlomo. In the 17th century, Rav Meir Shapiro’s ancestor, the “Rebbe Rav Heshel,” served as rav of Lublin and teacher of Rav Dovid Segal (the Taz) and Rav Shabsai HaKohein (the Shach).

The golden age of Torah in Lublin ended with the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648–1649, known as gezeiros Tach v’Tat for the Hebrew years when the bulk of the destruction occurred. More than a century later, the chassidic movement arrived in Lublin.

The chassidish character of the city was significant to Rav Meir Shapiro, who wished to fuse chassidic values with Torah supremacy. At the turn of the 19th century, one of the most influential tzaddikim in the history of Polish chassidus, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz (1745– 1815), the Chozeh of Lublin, established his court in the city. Some 50 years later, Lublin was graced with the founders of the Lublin chassidic dynasty as an offshoot of Ishbitz. Its leaders, Rav Leibel Eiger (1815–1888) and Rav Tzadok HaKohein (1823–1900), originated from non-chassidic backgrounds. The Eiger family continued to lead the city’s chassidic community until its destruction in the Holocaust, with Rav Shlomo Eiger serving for a time in a capacity in Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

From 1580–1764, Lublin was the seat of the “Vaad Arba Ha’aratzos” (Council of the Four Lands), the semi-autonomous political-administrative body for the Jews of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was the site of the first Hebrew printing press in the region during the 16th century. This led to an interesting phenomenon where many yeshivos in the Lublin district studied the same masechta, in order to assist the local publisher in completing the first set of Shas printed in Poland. This practice also proved to be a unifying force among the local yeshivos. Perhaps this tradition further entrenched the concept of daf yomi in Rav Meir’s mind.

In channeling the rich history of Torah learning in Lublin, Rav Meir Shapiro believed that he was not merely building a new yeshivah, but rather reviving the city’s rich heritage. The name Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin was full of meaning, and the revival of the historic period of Torah greatness in Poland, at a time when Torah study and observance were on the decline, was the mission of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

The Rebbe from London

Rav Shalom Moskowitz was born on 17 Kislev 1878 in Vyrbranivka, near Lvov. One of 17 children, his illustrious lineage is traced to Rav Yechiel Michel of Zlotchov, the Zlotchover Maggid (1731–1786), while his grandfather Rav Yoel was the son-in-law of Rav Meir of Premishlan. The family were devoted Belzer chassidim and he was named for the first Belzer Rebbe, the Sar Shalom (1781–1855).

His early Torah education was under the tutelage of Rav Eliyahu Shmuel Schmerling of Babruysk and Rav Shalom Mordechai Schwadron of Brezan (the Maharsham), who deeply influenced Rav Shalom with his clear and decisive halachic rulings. His exposure to the teachings of Kabbalah came through his uncle Rav Leibish Halperin.

Physically Rav Shalom was an imposing figure, tall and regal. His radiant countenance, accentuated by a flowing white beard, commanded respect. His 16-year tenure as rabbi of Shatz ended following a disagreement with community leaders over a local shochet. Refusing to compromise on halachic principles, he left the town, without any idea how and where he would earn a living. Marrying his cousin Shlomtze in 1897, their life journey took them through various European cities, including Tarnow, Cologne, and eventually London, where he resided for the last three decades of his life.

His commitment to Torah study was unparalleled, and he often dedicated 18 exhaustive hours daily to his davening and learning. In the years preceding his passing, despite having suffered the loss of his beloved wife and five adult children, he remained steadfast in his rigorous study routine. With only his daughter Miriam Chaya at his side, he poignantly remarked, “Were it not for the Torah that is my delight, I would have perished in my anguish” (Tehillim 92). A testament to his erudition came from the Chazon Ish, who once remarked, “Der Rebbe fun London kenn lerenen — the London Rav is a scholar.”

Rav Shalom’s quest to master both the hidden and revealed Torah was vast and unique. When he passed away in London in 1958, he was deeply engrossed in the writing of Daas Shalom, a commentary on Chumash arranged according to the order of Perek Shirah. To ensure accuracy and gain a profound understanding of the subject matter, he studied zoology and made regular visits to the London Zoo. He was also interested in astronomy and botany and frequently visited Munich’s Sternwarte Planetarium while residing in Germany. On one occasion he drew the attention of the curator to two errors in the description of the exhibits.

The Shatzer Rav’s legacy remains an inspiration and continues to this day with frequent visits to his gravesite in London. At the Enfield Adath Yisrael cemetery, his ethical will is emblazoned across the wall of the ohel:

It’s well known that I have always tried to help people to repent of their evil ways, and thanks to Hashem I have succeeded many times. Therefore, whoever is in need of any kind of yeshuah (salvation) or refuah (recovery from illness) for himself or for someone else, should come visit my kever, preferably on a Friday before noon, and light a candle for my neshamah and make his request. Let him state his name and his mother’s name. Then I shall certainly intercede with my saintly forefathers that they should awaken G-d’s mercy for a yeshuah or refuah.

But there is a definite condition attached: the person concerned must promise to improve his standard of Yiddishkeit. For example, he whose business is open on Sabbath must promise to keep it closed. He who shaved his beard with a razor blade should now remove it in a way that is permissible. A woman who does not cover her hair must promise from now on to wear a sheitel (wig). All this must be clearly known to those who come to my tomb. They must keep their promise and should not try to deceive me, G-d forbid, for I shall be very angry. Unfortunately, there is already too much deceit in this world.

Chapter II: A Vision for Poland’s Yeshivos

A Yeshivah for Every Court

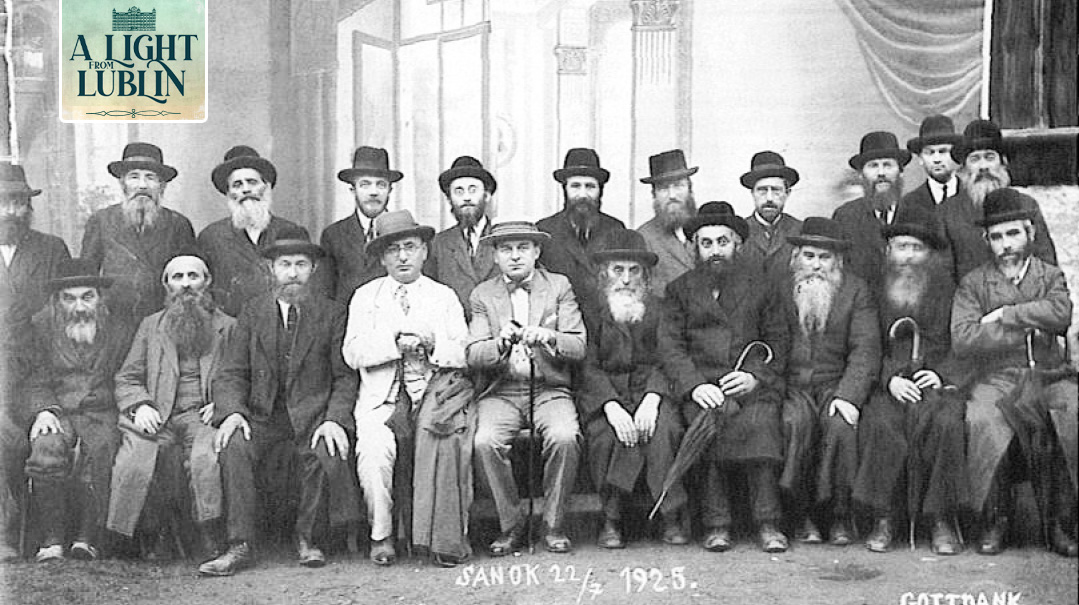

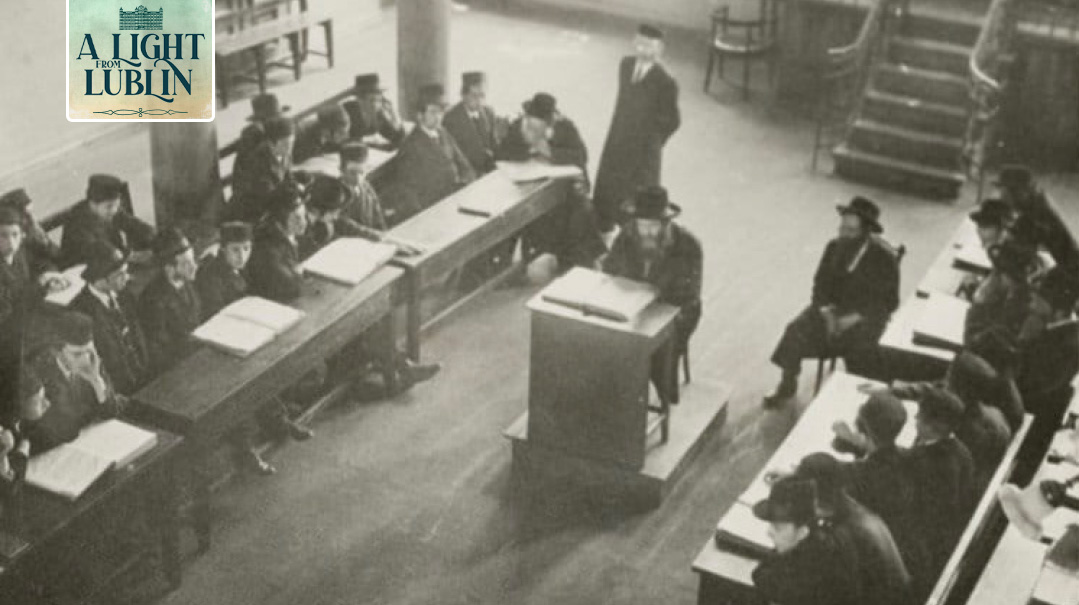

IN 1921 Rav Meir Shapiro was appointed rav of Sanok. His acceptance included the stipulation that he bring the Galina yeshivah along with him, and in its new location the yeshivah grow in both quality and quantity. With nearly 300 students, Yeshivah Bnei Torah was one of the largest in Poland.

Yet despite the success of his own yeshivah, Rav Meir noticed that Poland’s Torah landscape was sadly bare of similar institutions. Despite its storied past as a bastion of Torah study and chassidic life, the country for the most part lacked the structured, institutionalized yeshivos that had developed in Lithuania during the 19th century.

This distinction was stated explicitly in an oft-cited responsum of one of the fathers of Galician chassidus, Rav Chaim Halberstam (1797-1876), the Divrei Chaim of Sanz. In 1862 he wrote, “Yeshivos are not found in our land [Galicia] for a number of good reasons… rather [young men] sit in groups in the beis medrash and they study Torah, Talmud, and Tosafos.”

Unlike traditional yeshivos, Polish Torah centers revolved around charismatic personalities, usually a town rabbi or chassidic rebbe. The yeshivah of Sochatchov, for example, drew its spirit from the revered Rav Avrohom Borenstein (1838–1910), the Avnei Nezer. In a similar vein, the 20th-century yeshivah in Sokolov was steered by the Avnei Nezer’s great-nephew, Rav Yitzchak Zelig Morgenstern (1866–1939), the Sokolover Rebbe.

This pattern persisted in greater Galicia as well. Bobov’s yeshivah network, Etz Chaim, was under the guidance of its rebbe, Rav Ben Tzion Halberstam (1874–1941), the Kedushas Tzion. Tarnopol’s yeshivah was led by Rav Menachem Manish Babad (1865–1937), the author of the Chavatzeles Hasharon, while Rav Aryeh Tzvi Fromer (1884–1943) established Kozhiglov’s yeshivah. The character of these institutions hinged on the educational qualities of the individuals who led them, not on a collective institutional approach or organized curriculum.

Moreover, these leader’s positions as roshei yeshivah were secondary to their primary function as chassidic leader or communal rabbi. Even in the yeshivah in Sochatchov, where the Avnei Nezer primed the next generation of Polish geonim (The Kli Chemda, Chelkas Yoav, Eretz Tzvi, and Nefesh Chaya were just some of the classic seforim authored by his students), no sleeping quarters were provided, nor were there any meal arrangements or financial support.

In his monograph on Polish yeshivos, Hillel Seidman (1907-1995) points to an additional challenge. Chassidim were generally quite particular regarding their children’s education and went to great lengths to ensure that their children weren’t exposed to foreign influences. “Foreign” in this context wasn’t limited to blatant digressions from the traditional path but included any deviation from the specific customs and values associated with the particular chassidic dynasty of the family. Despite the intense Torah study that existed in the kloisz in Belz, one would be hard pressed to find a Gerrer chassid studying there and vice versa.

Most chassidic yeshivos in Poland were identified with a specific dynasty. Eitz Chaim was affiliated with Bobov, Bais Yisrael was founded by Rabbi Yitchok Menachem Danziger (1880-1942) of Aleksander (which, after Ger, was the second largest chassidic dynasty in Poland), Sochatchov and various other courts of Polish chassidus each had their own institutions.

One exception was the vast network of Keser Torah yeshivos established and funded by the Rebbe of Radomsk, Rav Shlomo Henoch Rabinowitz (1882–1942), in interwar Poland. At its peak it counted 36 yeshivos with over 3,000 students. These yeshivos were less “partisan” and attracted chassidim of all stripes. But outside the Keser Torah network, yeshivos were limited to individual chassidic streams.

Rav Meir Shapiro was determined to recalibrate this scenario. While deeply respecting the existing structure, he envisioned a yeshivah system in Poland mirroring the administrative and academic rigor of Lithuanian yeshivos, where elite students could shine in an environment uniquely tailored to their abilities, and where tribal differences were laid aside at the entrance to the beis medrash. It would be a place where a talented chassidish bochur could be accepted and valued primarily for his Torah knowledge, not for his particular chassidish affiliation — and where he would find elite students with whom to climb spiritual heights.

Boro Park real estate developer and philanthropist Max Jonas (center) is pictured along with local rabbanim and dignitaries on a 1925 visit to his hometown of Sanok, where he dedicated a new cheder and medical center. He would later assist Rav Meir on his fundraising trip to America, and joined the international board of directors of the yeshivah. Tragically, he died just weeks apart from Rav Meir at the age of 41

Rav Shlomo Henoch Rabinowitz of Radomsk (far left) alongside his devoted chassid Reb Naftali Besser and the rebbe’s son-in-law, the great gaon Rav Dovid Moshe Rabinowitz, who served as rosh yeshivah of the Keser Torah yeshivah network

Bread & Salt

Poverty was another factor Polish yeshivos had to contend with, and Rav Meir aimed to confront this challenge as well. Yeshivah students were particularly affected by the poor economic conditions. Rav Meir saw their degraded status as an impediment to their learning and an insult to their standing as honorable members of society.

The memoirs of Alphonse (Avraham) Honig (“La Métamorphose du Juif errant,” published in 1978 by La pensée Universelle) provide a firsthand account of a student in Sanok, who yearns to study in Rav Meir’s yeshivah, but can’t tolerate the austere lifestyle:

Despite all my various difficulties, despite my loneliness and homesickness, which I have described in the preceding pages, I nevertheless have the opportunity of being a student of Rabbi Shapiro. Attending his morning classes is a privilege to which all young Talmudists aspire. The atmosphere there is extraordinary, and every day we discover something new. When I get up in the morning and think of the classes I am about to attend, I feel pious joy. I quickly get dressed and say my prayers so as to arrive early and watch Rabbi Shapiro enter the classroom. He energetically crosses the room, ascends to his podium, and, before beginning the class, casts a penetrating glance over his audience.

A thrill of excitement goes through my entire body whenever I feel that his eyes are resting on me. There is such silence that one can hear a fly. The whole room transforms itself into eyes and ears and prepares to listen. His words, like a prophecy, seem to come from afar. All the students sit hypnotized during the three-hour class. His method of teaching is both novel and original. For the subject of his class he has chosen the tractates Berachos and Mikvaos. These two tractates are not taught in any other yeshivah — and rare are the Talmudists who have studied them.

I would like to see the look on the faces of the Talmudists from home when they hear about this, because for them the study of Aggadah is a waste of time. But Rabbi Shapiro, thanks to his great knowledge and intellectual powers, succeeds in giving them new meaning, and interpreting them in a way that fascinates his students. His interpretation is fiercely debated among the students, and each gives his personal version, as is the practice in other yeshivos, with regard to the legal tracts. Rabbi Shapiro is not only a gaon, respected for his Talmudic knowledge, but the students have great affection for him. He, too, loves them like a father. He calls them by name, despite their great number. He knows the material difficulties and emotional difficulties of each student.

The memoirist describes the shame associated with the Teg system, under which each night the students were hosted by local families on a rotation basis. They often felt unwelcome, especially since many families were poor and hardly able to provide for their own children. Other times the opposite held true:

Obviously, it is quite humiliating to go to a different benefactor each day. For those boys with a sense of self-esteem, and I think I am one of them, it is unbearable. I prefer to tighten my belt and make do with the little money I get, rather than eat my fill at the home of some portly citizen where I would have to listen to his platitudes and endure the arrogant and mocking looks of his children.

Avraham Honig saw the pain Rav Meir suffered from having his students take part in this system, and his efforts to provide them with some pocket money so they could alleviate their hunger.

It was worth the suffering to acquire the knowledge of the Torah, as it is written in the mishnah: “A little bread with salt… and sleeping on the ground, is the path to the Torah.”

But Rav Meir Shapiro himself found this saying to be wrong when it comes to young men who are devoting their lives to the Torah, and added a question mark, which changes the meaning of this sentence completely: “Is eating bread and salt and sleeping on the floor really the way of the Torah?”

Rav Meir exiting a meeting in Vienna along with two leaders of Agudas Yisroel, Rav Aharon Walkin of Pinsk and Rabbi Dr. Samuel Spitzer, Chief Rabbi of Hamburg

In the Town Square

IN 1922 Rav Meir was implored by Agudas Yisrael to represent the party in the upcoming elections to the second Polish Sejm (parliament). The first Sejm in the Second Polish Republic (1919–1922) included two representatives of Agudas Yisrael (Rabbis Moshe Eliyahu Halpern (1872-1921) and Avraham Tzvi Perlmutter (1843-1930)). Before the next election, a more experienced Agudas Yisroel was better organized and sought candidates who would draw both more respect and more voters.

On the surface, a rosh yeshivah such as Rav Meir was not the most ideal candidate — but Avraham Honig’s memoirs explain why Agudas Yisroel wished for him to serve as their candidate:

A custom existed in Poland that when the Prefect (regional governor) visited his constituents in one of the towns in his region, upon entering the town he is received by representatives of all the communities. Each delegation in turn approaches the carriage of the Prefect to pay their respects and their grievances. The Jewish delegation is usually led by the town rabbi carrying the Torah.

Rabbi Shapiro, of Romanian origin, having lived in Poland for a short time, did not know a word of Polish. [He later gained a rudimentary fluency of the language.] The representatives of the Jewish community were very embarrassed about the speech that Rabbi Shapiro had to make in honor of the governor. He, on the other hand, did not seem worried at all.

That day he gave his class as usual, in no hurry. After it was over, he had one of the students who was a graduate of the University of Krakow translate his speech [from Yiddish into Polish]. A few moments later, he left to head the delegation to receive the governor.

To the great satisfaction of the Jewish notables and to our great astonishment, he delivered his speech without the aid of the notes prepared by the student.

Initially, Rav Meir turned down the Agudah’s request to serve in a political capacity, knowing well that he’d have to leave his beloved yeshivah in order to be present in Warsaw during government sessions. But the Rebbes of Ger and Tchortkov believed his candidacy was essential. In his unpublished memoirs (later translated into English by Charles Wengrov and published by Feldheim as A Blaze in the Darkening Gloom), his student Rabbi Yehoshua Baumol cites a mishnah in Taanis (2:1) to explain his logic. “In a time of peril, a sefer Torah is taken out to the town square.” This “living sefer Torah” was thus compelled to exit the confines of the beis medrash for the public square, where his talents could be utilized to further the needs of the Polish Orthodox community.

Ultimately, Agudas Yisrael persevered in the election, garnering six seats in the Sejm, mainly due to the bump it received from joining a voting bloc that consisted of Jewish and minority parties. The Agudah deputies now included (in formation) Reb Eliyahu Kirschbraun, Rav Aharon Lewin, Reb Leibel Mintzberg, Reb Feivel Stempel, Reb Leizer Syrkis, and Rav Meir Shapiro.

Dr. Simcha Bunim Feldman (1874–1954), an attorney turned educator, served as a deputy in the Sejm representing Mizrachi at the same time Rav Meir Shapiro was representing Agudas Yisrael. The Yizkor book for the city of Biala describes Feldman as a righteous individual who was respected by all — even the chassidim — for his religious devotion.

In 1938 he penned his memories of Rav Meir in the Mizrachi newspaper HaTzofeh:

His sense of responsibility was very strong. I will never forget his enthusiasm and energy, when he took part in a stormy opposition that the Jewish Caucus organized during a session of the Sejm, as a protest against proposed legislation, which was completely directed at the Jews and their economic position. He pounded on the bench with us for a full hour, and cooperated with us in an action whose intent was to protest the discrimination against Jewish citizens in the legislative field. In the period of the second Sejm, which lasted five years, I was lucky enough to greatly benefit from the light of his Torah and wisdom, from the many conversations we held on the benches of the Sejm as well as other occasions.

One Shabbos (parshas Vayishlach, 1922) when the Sejm and Senate came together for the legally required “National Assembly” to vote for President, we all arrived early at the Sejm building. The voting took all day. There were seven candidates. This caused the votes to be so divided that no single candidate received a definitive majority, requiring the voting process to be repeated five times, and following each cycle, the candidate with the least number of votes was taken off of the candidate list. So we were forced to remain in the Sejm building, which is far from the Jewish neighborhood, until the evening. When it came time for Minchah, we davened together in the Caucus’s room, and then the issue of Seudah Shlishis arose. One of the members obtained some rolls for us, and we ate Shalosh Seudos while the Sejm was tallying the votes after a new round of voting.

After we finished the meal, I suggested to Rav Meir Shapiro that he share some divrei Torah, specifically of halachic nature. He started saying a nice chiluk in Maseches Yoma, and we were enchanted by his style of lecture and enlightening explanation. It seemed that the walls of the Sejm never heard such a pshetl. To our dismay, he was unable to conclude his sharp pilpul. Suddenly the hallway bells started ringing a long ring, calling us to the Sejm hall for a new round of voting. The pshetl was stopped in the middle, and we were successful in the final round. From this round, Gabriel Narutowicz came out as the President of the Polish Republic. As we exited to the street after this victory, masses of Poles were ready for us with curses, “blessing” us for our “Jewish President” (he was referred to as such because he was elected with the assistance of the Jewish parties). The second Shabbos, President Narutowicz was murdered by the artist and writer Niewiadomski. I didn’t hear the end of the chiluk on Maseches Yoma as we had many other chilukim afterward that occupied our thoughts….

Once, we traveled together from Warsaw to Lvov. We were together in the first-class cabin, due to the privilege that was given to us as delegates to the Sejm. We departed at night, and we discussed various matters until the late hours after midnight. Primarily he shared with me divrei Torah. On that night he revealed to me his plans for daf yomi, which he intended to present to his colleagues in the Agudah. The delegate to the Polish Sejm never forsook for a minute his love of Torah, and his life mission to spread Torah to the masses.

Rav Meir would serve in the Polish Sejm for more than five years, though as time went on, he focused his attention on other endeavors, primarily two of which would completely change the face of Torah learning.

A rare photo of Rav Meir Shapiro (right of center) surrounded by fellow Agudists at the first Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna in 1923

Chapter III: A Yeshivah Like No Other

Two Children

Though Rav Meir Shapiro and his wife, Malka, did not have biological children of their own, he refused to consider himself childless. His close student Rav Shmuel Wosner recalled a summer evening stroll in the gardens of the yeshivah, during which Rav Meir declared himself the father of two offspring: the enduring legacies of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin and daf yomi.

The first of his “offspring” had its genesis in 1912, when Agudas Yisrael was formed at a conference in Katowice, Poland. When news of this historic gathering reach Rav Meir, he famously commented:

“I wondered how Rav Chaim of Brisk, a Lithuanian gaon, would find a common language with Reb Yaakov Rosenheim, who grew up in German Frankfurt, or how a Jew from Tzfas or Poland would communicate with his colleague from Holland or America. Then I opened a volume of Maseches Berachos and realized that the Mishnah was written in Eretz Yisrael, the Gemara was written in Bavel, Rashi learned from teachers in Germany and wrote his commentary in France, the Baalei Tosafos lived in France, the Maharsha had resided in Lithuania, and the Maharam in Poland. Each most certainly had different qualities and characteristics, but the common pursuit of Torah truth unites them all; I then understood that Agudas Yisrael represents the Torah outlook, and it is this common thread that unites us all, from one end of the world to another.”

(This quote has been commonly attributed to a speech Rav Meir delivered at the Katowice Conference, although according to this author’s research on the subject, Rav Meir was not in attendance, so the speech was likely delivered at a later Agudah event.)

Rav Meir’s observation about the unifying power of Torah learning would sow the seeds for his proposal at the next gathering of Agudas Yisrael in the summer of 1923 (delayed nearly a decade due to World War I), the groundbreaking concept of daf yomi.

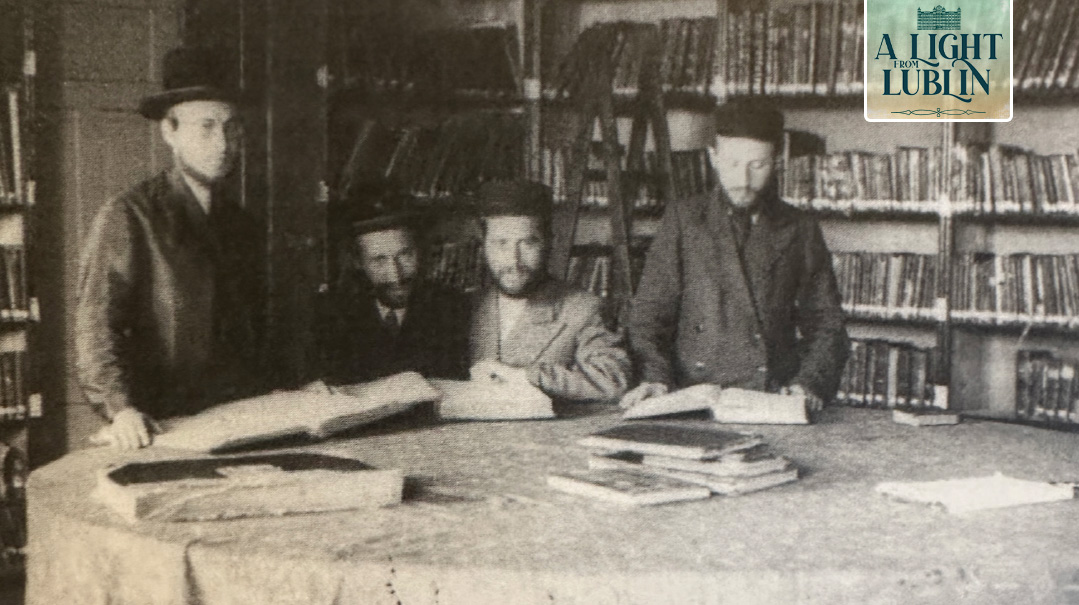

The Keren HaTorah committee, which helped oversee and fund projects like Sarah Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov and assisted with the establishment of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, consisted of important Torah activists from across Europe

The story of Rav Meir’s speech at the 1923 Knessiah Gedolah and the subsequent commencement of the first daf yomi cycle a few weeks later on Rosh Hashanah have become a vaunted chapter in our nation’s annals. Few, however, are aware of the rest of that groundbreaking speech he delivered on 7 Elul at the inaugural Knessiah in Vienna, where he laid the seeds for his second “child,” Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin (which he would officially announce four months later). New York’s Yiddishe Tageblatt shared Rav Meir’s emotional words:

Owing to the World War, two generations were denied a life of Judaism. Jewish children who were [as young as] ages 14–15 [at the start of the war] were subject to military responsibilities, and were forced to cease their studies. The younger generation, those who were ages four to six, were deprived of chadarim to learn in, and grew up lacking any Jewish education. Thus two generations were lost, and unless we do everything we can to save the third generation, Judaism risks the danger of a spiritual death.

We have, however, also lost much Jewish talent that we could have taken pride in. How many sharp Jewish minds were neglected? Should one wish to present a demonstration of this catastrophe, the following anecdote, which I witnessed, can serve as an illustration:

A year following the [end of the ] war, a 15-year-old boy approached me and asked to be accepted into my yeshivah. He comes from the village of Bialozorka, near the Russian border. The Bolsheviks had entered [the village] several times. Some of the Jews fled, and he had nobody to teach him Torah. He had already been to Lemberg, Warsaw, Lodz and Bialystok, but nowhere was he wanted or accepted, since he was destitute and would need to be supported. So, he was advised to approach me.

It was, however, a difficult period for me as well. [My] town [of Galina] was impoverished, and inflation was rampant — I had to struggle greatly to sustain the yeshivah. “But one boy,” I told him, “we will certainly find space [for].”

At this, the boy began to sob: “If I would only [be speaking for] one boy, I would have already found a place. We are, however, a group of ten boys from our town. We swore to each other that we would all be accepted to yeshivah together, and none of us would leave any of the others behind.”

“This was the story,” says the Sejm member, as tears trickle down his face, “and I did everything to ensure these boys were taken care of. And now, listen to this: the [leader of this group] studied at my yeshivah for three months. At the final examination at the end of the term, he knew 270 blatt of Talmud, with commentaries, by heart! He will develop into a great leader of the Jewish people. His name is Elkana Weizman. His fellow students are just as brilliant as he.”

If those in the West, who support the Jews of Eastern Europe, would be able to understand the importance of not losing these phenomenal Jewish talents, they would perhaps provide an even greater measure of support. We should be eligible for a great deal of credit, since we offer the best of guarantees. No government on the globe can offer such high returns. For every hundred dollars [given by] the American Jewish community, we can repay the loan with a Jewish genius, with a great Jewish leader, who will be the pride of the whole nation and the entire world.

Rav Meir seated at the dais at the second Knessiah Gedolah of Agudas Yisrael in Vienna in August 1929

Can’t You Hear It?

AT the Knessiah, Rav Meir met a businessman and philanthropist named Shmuel Eichenbaum from Lublin. Poland echoed with tales of his generosity, with hardly a single chassidic rebbe untouched by his largesse.

The camaraderie that developed between Rav Meir and Reb Shmuel led to an invitation for Rav Meir to spend a Shabbos in Lublin. There his host led him along the paths of Lublin’s rich past, from the hallowed Maharshal Synagogue to the whispers of the ancient cemetery. But it was when Shmuel Eichenbaum pointed out his recently acquired property in the heart of Jewish Lublin at 57 Lubartowska Street, that the destiny of Torah in Poland took a defining turn.

What intention, Rav Meir wondered aloud, might have driven Eichenbaum to purchase this prime real estate? Before Eichenbaum could even respond, a gleeful Rav Meir interjected, assuring Eichenbaum that the Divine plan was clear to him. One could almost sense the palpable energy of Rav Meir’s vision for that piece of land.

Following Shabbos, a Melaveh Malkah was held at the Eichenbaum residence. Addressing friends and family of Shmuel Eichenbaum, Rav Meir spoke with passion. “Ich vil epes iberlozen noch zich,” he said, “I desire to leave a legacy.” For a rav bereft of offspring, what better legacy than a yeshivah, a beacon of Torah?

Eichenbaum, seeing an opportunity to contribute, offered his newly acquired land for this purpose. Rav Meir grabbed his host and practically danced him over to the site, even though it was well past midnight. Once they reached 57 Lubartowska, Rav Meir, in an act of complete jubilation, prostrated himself with his ear facing the ground and sang out, “Can’t you hear the kol Torah already?”

Yet no great deed ever goes unpunished. When people heard about Eichenbaum’s generous gift, voices of dissent rose, attempting to sway him from his generous pledge. But the bond forged in Vienna, and solidified in Lublin, remained unbroken. A written agreement was signed, the first major step of Rav Meir’s grand journey complete and on its way to its grand realization.

(Amazingly, Chaya Mindel Eichenbaum summoned her husband to a din Torah over the matter — not because she opposed the gift, but because he granted it without her involvement, limiting her own merit in the endeavor. Ultimately, a workaround was found so that she could share in the mitzvah.)

Property in hand, Rav Meir began in earnest to collect funds toward the construction of the grand edifice he envisioned, one that would eclipse all other yeshivos. Four months later, in December of 1923, Rav Meir felt confident that the project was on its way to becoming a reality and drafted a letter to Polish Jewry that appeared in local newspapers as well as other outlets:

Lublin.

We direct our gaze to the days of old, to the golden age of the Council of the Four Lands, when a world-class yeshivah existed here that served as a center of Torah in the state of Poland. Also, Torah and halachic instruction went forth from it to all of the Jewish people.

We have gathered today to raise up the yoke of Torah, to resurrect a world-class yeshivah under the name: Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

To this end, we have decided to erect a massive building that will contain classrooms, dormitory quarters, and a cafeteria, so that 500 gifted students will be completely cared for, spiritually and physically.

And the following individual will always be remembered favorably: the philanthropist Reb Shmuel Eichenbaum, who was moved to donate to us as a permanent gift — a suitable plot of land the size of 3,500 square meters.

May Hashem show his kindness to us all, and help us succeed in implementing His will to restore the crown [of Lublin] to its ancient glory, and this holy, precious institution, an institute to nurture Torah and yiras Shamayim, will soon stand in all of its beauty, to the glory of global orthodox Jewry.

We the undersigned

16 Teves 5684, Shabbos 43

Meir Shapiro, Rabbi of Sanok

Shmuel Eichenbaum

Moshe Tsheransky

Moshe Eisenberg

Yechezkel Ehrlich

Rav Meir at a gathering along with prominent members of the Lublin community: Seated L-R: Moshe Eisenberg (chairman of the Building Committee), Shmuel Eichenbaum (donor of the yeshivah property), Rav Meir, Herschel Zilber (president of the Lublin kehillah)

Detractors Without & Within

While many rejoiced at the news of this exciting project, there were the inevitable detractors. The local radical Jews of the Bund looked upon the large expenditure as wasteful and an affront to their beliefs, using the headline, “Concerning the Resurrection of the Shtreimel” in an article about Rav Meir’s initiative. Rabbi Dr. David Slavin (whose tireless research on Rav Meir Shapiro has been essential to this author) unearthed an article from the anti-religious Folzeitung which he summarized as follows:

The article stated that the Gerrers knew how to use the press for their own purposes, and were now pulling all of the Jewish people into the mikveh, the masses into the cheder. The article conceded that the building was impressive, but stated that it would be more appropriate to house a benk (bank in Yiddish) rather than benk kvetchers (bench huddlers). This was a brilliant play on words — “bench huddlers” is a reference to yeshivah bochurim who sit on benches studying all day.

Instead of modernizing, students at the yeshivah would be told to hold onto their old ways. Students would sit and study shnayim ocha’zin be’dalus — two [litigants come before the court] grasping poverty — this is another cynical play on words, referencing the first mishnah of Bava Metzia, but substituting the word tallis (garment) with dalus (poverty). The author describes all the modern facilities, but how the outdated students would misuse them for old-fashioned religious purposes.

In addition, anti-Semitic elements found it unacceptable for such a showy edifice to be erected in the heart of Lublin, and arranged for the government to halt construction on the yeshivah’s lot three times.

At one point, a group of Polish clergymen claimed that the yeshivah’s land had formerly housed a church and had construction halted in protest of this “desecration.” They even went as far as erecting a large wooden cross on the site one night. Eventually, pressure from Agudah’s political machine ensured the project received the proper permits.

Complaints about the palatial edifice being erected came from both Lithuanian roshei yeshivah as well as some in Polish chassidic leadership. Economic woes still bedeviled the Jews of Poland and many “competing” mosdos complained to Rav Meir that the hundreds of thousands of dollars he needed to collect could be used instead to erect dozens of other yeshivahs, built in more pedestrian style. As always, Rav Meir was prepared with an answer, this time in the form of a parable:

One day, in a large chicken coop, everyone was surprised to find a large turkey among the chickens. The chickens objected, saying that the feed the stingy master offered was barely enough to sustain them, let alone their new “housemate.”

The turkey urged them not to worry, reassuring them. “True, I have a bigger appetite to sate. However, let me assure you that because I can scream and make a racket louder than all of you, I will leave the master no choice but to come and feed us more often and generously. As a result, the entire coop will be better fed.”

Rav Meir explained that he was the “turkey” in the fundraising efforts of Poland. When he encouraged people to donate money, they would be inspired to donate — not only to his cause, but also to many others. As a result, everybody would benefit. Rav Meir wanted to expand the total “pie” of donations and he was also certain that Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin would enhance the image of Torah learning, in general. He was convinced that people would spend money on causes that were important to them. If the public face of Torah learning came to be valued and perceived as honorable, then funds available to all learning institutions would increase.

The crowd at the groundbreaking event held on Lag B’Omer 1924. The Tchortkover Rebbe can be seen at center

As illustrated in Rav Meir’s allegory, his motivation in building the yeshivah was to raise the public face of all Torah learning. And considering the lowly status accorded to yeshivah students, a transformation was sorely needed.

Israel’s former Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau (who proudly carries the name of his cousin Rav Meir Shapiro) shared that at the groundbreaking for the yeshivah, Rav Meir publicly expressed his gratitude to the “thieves of Poland” for their role in the project.

“Why am I planning to build a yeshivah with a dormitory?” he asked. “For this, we have to be grateful to the thieves of Poland. If there were no thieves in Poland, the storeowners wouldn’t allow the yeshivah boys to sleep in their shops because they wouldn’t need (night) watchmen. And if the boys didn’t have where to sleep, they would not come to cities like Warsaw and Lublin to study Torah. So we have to thank the thieves for the Torah studied in Poland.” He then switched from irony to passion: “I will not allow this situation to continue! This is why I am building a dormitory!”

In an interview with the producers of “Only with Joy,” a documentary on the life of Rav Meir, Rav Yisroel Yehoshua Eibeshitz, author of BeKrovai Akadesh (1916–2019), told of his experience studying in a Polish yeshivah in the 1920s: “In order to get a place to sleep I was locked into a store every night as a watchman. There was no water or bathroom. Had a fire broken out I could’ve been burned to death. Every morning the owner frisked me from top to bottom and checked even my shoelaces in case, G-d forbid, I might be stealing something. That was the system. I was a 13-year-old boy the first time I left my mother’s apron and came to a strange place to study Torah. Every day my blood was spilled. All this Rav Meir Shapiro wanted to change.”

Not only did Rav Meir aim to build a dormitory, he wanted the building to be aesthetically impressive. His students point to his relationship with the Tchortkover Rebbe, Rav Yisrael Friedman, the grandson and namesake of “Der Heilige Ruzhiner,” in order to understand his reasoning.

Once during a visit to the yeshivah by the Sadigura Rebbe, another Ruzhiner descendant, Rav Meir took the opportunity to articulate the link between the chassidus of Ruzhin and the yeshivah.

“It is well known,” he said, “that the derech of chassidus comprises a number of different pathways. The path of Ruzhin is that of Hod Sh’biTiferes, splendor and majesty. Its goal is to beautify the Torah and the mitzvos. Just as a diamond needs the correct setting to showcase its qualities, so too each mitzvah needs its own special place and setting.

“The Ruzhiner demanded that the external trappings of the mitzvah also be beautiful and glorified. This is the derech of our yeshivah, whose source is rooted in this derech of majesty and whose purpose is to show the true splendor of our holy Torah.”

The home and beis medrash of the Tchortkover Rebbe

Go West

IN order to garner large-scale support for the project, Rav Meir planned a grand groundbreaking event (as portrayed earlier) for Lag B’omer of that year. The event attracted dozens of prestigious rebbes and rabbanim from across Poland as well as thousands of spectators and even more “well-wishers” — but far too few donors.

Sensing that he’d exhausted his fundraising opportunities in Poland, Rav Meir decided to travel to Western Europe, where he thought he’d find more sympathetic Jews — who would be capable of larger donations as well.

In “Keeper of the Law,” memoirist Eli Ginzberg tells of Rav Meir’s visit to Germany: “The Frankfurters in the congregation were fond of telling, among themselves, the story of Rav Meir Shapiro’s visit. ‘Rabbiner Shapira’ was both impressed and dismayed at the manner of Jewish observance; impressed at the organization of the Frankfurt community and dismayed that it tended to override the kind of fervor he knew as a chassid.”

During this trip, Rav Meir formed a close bond with Rav Shlomo Zalman Breuer (1850 – 1926), son-in-law of Rav Shamshon Raphael Hirsch, who he’d met years earlier when traveling to Frankfurt to get medical attention for his wife. Rav Meir affectionately referred to Rav Breuer as the “Western Wall,” because he served as the “spiritual line of defense” in the country west of Rav Meir’s home in Poland.

When Rav Breuer asked for Rav Meir’s opinion on the davening style of the Frankfurt community, Rav Meir pointed to a sign outside promoting kosher ice cream, telling Rav Breuer that the davening was the same as the ice cream: “frozen with the hashgachah of the Rav.”

This point was not lost on German Jewry, who gave Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin a backhanded compliment when they wrote in Der Israelite that the yeshivah would be a turning point for chassidim, who would “now focus on scholarship instead of being drinkers.”

Rav Meir had high hopes for his August 1924 visit to England, arriving following a successful visit to France. He was excited to reconnect in London with the Rebbe of his youth, the Shatzer Rav. (His all-encompassing grasp of history came in handy when asked by a reporter about any connections between Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin and the Jews of London. Hardly pausing, he replied that Menasseh Ben Israel (1604–1657), who played an important role in the readmission of Jews to England, sent his son to study in the great yeshivah in Lublin.)

While he had some successes in England, for the most part the trip was a disappointment. One day he traveled to a town outside London for an appointment with a wealthy man who contributed absolutely nothing. Rav Meir said sarcastically that he now realized the great extent to which England welcomed her guests. “While in Poland I have the privilege of traveling by train for gornisht (nothing) on account of being a Member of Parliament; here, too, I have traveled by train for gornisht.”

Rav Meir also traveled to Ireland as well as Switzerland, Belgium, and Holland, but he soon realized that there was only one place that might bring him the funding necessary to realize his dream: America.

Unlike most roshei yeshivah, Rav Meir would regularly conduct interviews with the media, even conducting press conferences on a regular basis to update both the jewish and secular media on the yeshivah’s progress

Chapter IV: American Dream

Across the Atlantic

ON the evening of August 15, 1926, the main railway station in Warsaw was packed with throngs of well-wishers, eager to escort the Piotrkower Rav as he embarked on the first leg of his voyage to the United States. Campaigning in the goldeneh medineh for the welfare of Eastern European Torah institutions was a popular fundraising tactic in the roaring 20s: nearly every major Lithuanian rosh yeshivah visited (at least once). During the course of his American visit, he would be joining up in some cities with Rav Meir Dan Plotzky (1866–1928), author of the Kli Chemda, who sought aid for the Mesivta of Warsaw.

In the months prior to his departure, Rav Meir published his sefer of responsa, known as Sh’eilos uTshuvos Ohr Hameir. He proudly carried with him several boxes of the new sefer, to distribute as gifts to the rabbanim and laymen who assisted him throughout his trip. The inscriptions from those seforim (of which this author has come across quite a few) have been helpful in tracing Rav Meir’s journey across the continent.

Rav Meir booked passage on the Cunard line’s HMS Majestic (the sister ship of the Titanic). He was accompanied on the journey by Moshe Eisenberg (a prominent member of the Lublin community) and Yosef Rappaport, the son of Reb Hirsh Rappaport (1830-1899), the gabbai of the Tchortkover Rebbe. The six-day cross-Atlantic voyage was unavoidably extended several hours due to the foggy weather, but finally, at 12:30 p.m. on August 25, the Majestic managed to dock at Pier 59 in New York City. The arrival of the young, charismatic Rav of Piotrkow (who also served as a delegate to the Polish Sejm) generated no small amount of publicity, which Rav Meir was more than happy to channel in pursuit of his vision.

In a news conference, Rav Meir shared with the reporters from the Yiddish and Anglo-Jewish press his plans to balance the yeshivah’s budget:

The Rabbi declared that according to calculations, the cost would be $100 per year per pupil. About 200 pupils will be admitted at the start, the number to be gradually increased to 1,000; at full capacity the budget will call for $100,000 yearly. The following unique plan will be adopted to collect this budget: 50,000 yeshivah boxes (pushkes) will be distributed in Jewish homes all over Poland, each box to contain an average of seven zlotys yearly. This will net an approximate sum of $35,000; one-third will come from pupils’ fees, and the last portion it is hoped for will come from a government subsidy and as yet to be discovered sources worldwide.

(Professor Shaul Stampfer has written extensively about the pushke campaign, which became the source of major controversy when Keren Rabi Meir Baal Haneis complained that they had the exclusive rights to distribute pushkes. The conflict resulted in a din Torah that ruled in Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin’s favor — though this hardly ended the controversy, which continued for years.)

A quick glance at the Jewish newspapers of the time makes it clear that despite all the positive coverage generated by his arrival, very little of it promoted the true purpose of his trip. One English-language outlet completely ignored the fact that Rav Meir had come to America on behalf of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin and reported that “Grand Rabbi Maier Shapira, a member of the Polish Parliament, together with his official staff, will shortly confer with President Coolidge at Washington on trade concessions between Poland and the US.”

Yet another report focused on Polish economics:

Rabbi Shapiro is one of the youngest members of the Polish Parliament and a good friend and active supporter of Marshal Pilsudski, the Polish Dictator. On his arrival in New York, he was given an official reception by Polish Government officials, including the Polish Envoy and Consul in New York.

When questioned as to economic conditions in Poland, the rabbi replied that “the Polish economic situation is not at all good. Poland is a country rich in natural resources. With an abundance of oil, natural gas, and coal, it has no capital to carry on its industries. Until credit can be established, Poland will be unable to utilize its riches.

“Businessmen are required by banks and private individuals to pay the high rate of interest of four percent per month. The government, however, lends money at a rate of one half that charged by the banks. Our budget system is working much better and at the present time is very efficient.”

Dismal Results

For the first several months, Rav Meir stayed within the confines of the New York metro area. During the week, his base of operations was the Broadway Central Hotel, while Shabbos and Yamim Tovim were spent with relatives and admirers, such as his cousin Mendel Shapiro of the Lower East Side (who served as president of the Melitzer Shtibel), and Rav Levi Yitzchak Kahane (d. 1950), a rav in Williamsburg.

On the evening of August 31, a grand welcome reception was held at the Beth Shalom Shul in Williamsburg. While New York’s Republican Senator James Wadsworth (1877–1952), then in the heat of what would turn out to be a losing reelection bid that fall, was unable to attend, he did send a close confidante to represent him: Assistant United States Attorney General William “Wild Bill” Donovan (1883–1959), who would later become the founding father of the CIA.

Despite all the publicity, the initial fundraising results were dismal. Rav Meir was so desperate to realize his dream that he accepted a job leading Yamim Noraim tefillos in a Williamsburg shul: davening from the amud, speaking, and even blowing shofar. (When his companion Moshe Eisenberg took ill on Simchas Torah and could not make it to shul, Rav Meir had the sensitivity to put on a full reenactment of the hakafos ceremony in their lodgings, pretending to take the “sefer Torah” out of the “aron’’ and dance, as if there was a large crowd present….) For his services, the shul presented him with $500 in addition to a gold cane.

Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that some American rabbanim simply disagreed with what they viewed as the extravagant plans for Chachmei Lublin. “Why build such an expensive building in such a poor country?” Rav Meir was asked. He responded with a parable about a poor man who was offered a high-risk business venture with a possibility of high profit margin. The pauper’s rebbe advised him that if he had wealthy relatives who could help him were he to fail, then he should proceed. “So too, similarly, in Poland, I feel we can rely on our rich relatives in America.”

Moreover, most of the American Rabbinate at the time aligned with Mizrachi, whereas Rav Meir was a prominent and unabashed Agudist.

When several Mizrachi rabbis who did sympathize with his vision suggested that perhaps he should cease identifying with Agudah to improve fundraising, Rav Meir famously replied: “If I would be ‘in the Agudah,’ I could simply resign… In reality, however, the Agudah is ‘in me’….”

Rav Menachem Mendel Hager, one of the current Vizhnitzer Rebbes of Bnei Brak, related the following episode at a 2013 gathering in Tzfas:

When my holy grandfather [the Imrei Chaim of Vizhnitz] ztz”l was in America in 1949 and 1950 in order to [raise funds to] establish Kiryas Vizhnitz, many people didn’t believe in his vision and even suspected that the whole operation was a scam and that he was taking the money for himself, G-d forbid. He persisted.

One evening, when he arrived back at the (Broadway Central) hotel, the owner honored my grandfather by allowing him to stay as a guest in the room where the Gaon Rav Meir Shapiro had stayed while serving as an emissary for his holy yeshivah in Lublin. The hotel owner told him that even Rav Shapiro suffered many embarrassments. He was broken over the lack of recognition of his mighty enterprise, and upon his arriving at the hotel, paced the corridors engrossed in thought. Suddenly, said the hotel owner, Rav Meir broke out in heartfelt song (one of many he would compose) to the words of Tehillim 94: “Im amarti matah ragli chasdecha Hashem yisadeini — If I said my feet have faltered, in Your kindness, Hashem, You have supported me.” He continued singing and dancing with dveikus until his great exuberance had its effect, and from all of the hotel rooms Jews emerged and gave him hearty donations.

The significance of this, said my holy grandfather, was the great merit of acting with mesirus nefesh in order to strengthen the Torah at any cost, and that is what enabled Rav Shapiro to implement his sacred task of establishing the study of the daf yomi. That same burning desire is what also helped him transform that program into an eternal heirloom for the Jewish People in every place they may be found. There are thousands of Jews following his light each day, and thanks to his efforts, the merit of the multitudes is established for all generations.

Rav Meir is greeted by a crowd on a visit to the partially completed yeshivah building following 13 months in America

New York & Beyond

Over the fall of 1926, aside from campaigning for Chachmei Lublin, Rav Meir visited and delivered shiurim at the yeshivos of New York: RIETS and Yeshivas Rav Shlomo Kluger on the Lower East Side, Mesivta Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin in Brownsville, and Mesivta Torah Vodaath in Williamsburg. He was particularly impressed with Torah Vodaath and took a special liking to the young man who was likely the continent’s youngest daf yomi maggid shiur: the 15-year-old Gedaliah Schorr (1910–1979), presenting him with a signed copy of his work Ohr Hameir.

Many years later, Rav Gedaliah would still recall the impassioned hesped Rav Meir delivered that autumn on the Lower East Side, marking the passing of Rav Yissachar Dov Rokeach (1854–1926), the third Rebbe of Belz: the room, estimated in the press as packed with 1,500 people, was filled with audible sobs.

At one point, Rav Meir led the entire assembly in sitting on the floor, as a sign of their immense mourning. He reminisced of his personal interaction with the Belzer Rav: The Rebbe was once extremely bothered — to the point of sleeplessness — about a problem he had discovered regarding the measurements of the Beis Hamikdash, remarking that the one who could resolve this difficulty for him would always be remembered by the Rebbe “both in this world, and the next.”

In the fall of 1922, the Rebbe’s son-in-law, Rav Pinchas Twersky (1880–1943), received a letter with a proposed solution to the problem from a relative of his, the 35-year-old Rabbi of Sanok, Poland, Rav Meir Shapiro (see: Ohr HaMeir, #25). The Rebbe was very pleased with this solution, declaring it “Toras Emes!” (Rav Meir offered to discuss the topic with anyone in the audience, following the conclusion of the event.)

In media interviews given shortly before departing Europe, Rav Meir had sounded confident that he could meet his fundraising goals in the United States within three or four months, leaving him time to travel to Mandatory Palestine before returning home. However, it soon became clear that this timeframe had been too optimistic, and that the New York City region alone could not provide the funding necessary to build the yeshivah (by the end of October, the campaign reported a total of $3,000 raised).

On December 16, a week after Chanukah, Rav Meir boarded a southbound train heading for Baltimore.

Aside from a one-day stopover in February, he would not return to New York City until the end of July, spending the next seven and a half months on a whirlwind of fundraising events crisscrossing the continent. From Boston to Denver, and as far north as Canada, he spent time in every major interwar Jewish community in North America, tirelessly campaigning in speech after speech for his vision of Chachmei Lublin.

By the time Rav Meir returned to New York City on July 29, he had $70,000 cash in hand for the cause, with additional funds in outstanding pledges. (The total raised after travel and marketing expenses was $53,000.) The tour of America’s heartland had indeed yielded fruit.

August 1927 was Rav Meir’s final month in the United States. While largely remaining in New York (speaking in Brownsville and the Bronx), he did attend several receptions in the cities of New Jersey, such as Passaic, Paterson, and Jersey City. On August 28, one year and three days after he stepped off the Majestic, a large farewell banquet was held for Rav Meir at Cooper Union in Manhattan. Rav Meir departed for Europe on the liner Berengaria on August 31, having penned a public letter earlier that same day in support of… Mesivta Torah Vodaath. For Rav Meir Shapiro, in the fight of his life to build Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, all yeshivos were sacred and deserved to be supported generously.

The Chachmei Lublin flag was designed by Rav Meir to embody the values and ideals of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. At its center, the flag depicted a Torah scroll supported by hands with “Yissachar” written on the sleeves, and a crown placed on it by the “Zevulun” hand from above. The black and white backdrop of the flag represents the partnership between Yissachar and Zevulun. This partnership highlighted Zevulun’s dedication to supporting the Torah studies of Yissachar.

The black and white colors also alluded to the saying of the Sages that the original Torah existed as black fire imposed over white fire. The Izhbitz-Radzyner Rebbe, Rav Yaakov Leiner (1828-1878) writes in his sefer Beis Yaakov, that while fire symbolizes light, sometimes its brightness requires moderation for comprehension. Just as we use a pinhole to view an eclipse, our bodies serve as vessels to limit the soul’s intensity. The concept of black fire is a necessary filter for the white light, making the Torah’s teachings more accessible. Additionally, fire symbolizes the removal of physical constraints. Thus, the black fire on white fire in the Torah illustrates its multi-layered meanings: some aspects may be beyond human understanding, while others provide guidance and purpose in our lives.

Chapter V: The Dream Comes to Life

Journey to the Land of the Yeshivos

AShis dreams for the yeshivah came closer to fruition, Rav Meir faced a pressing dilemma: Which derech halimud (approach to learning) should the yeshivah adopt? The luminaries of Lublin’s past — the Maharam of Lublin, the Maharsha, and the Maharshal — each had their distinct methodologies.

Rabbi Yehoshua Baumol expounds upon this quandary: