A LIFETIME CONTRACT IN THE BRONX

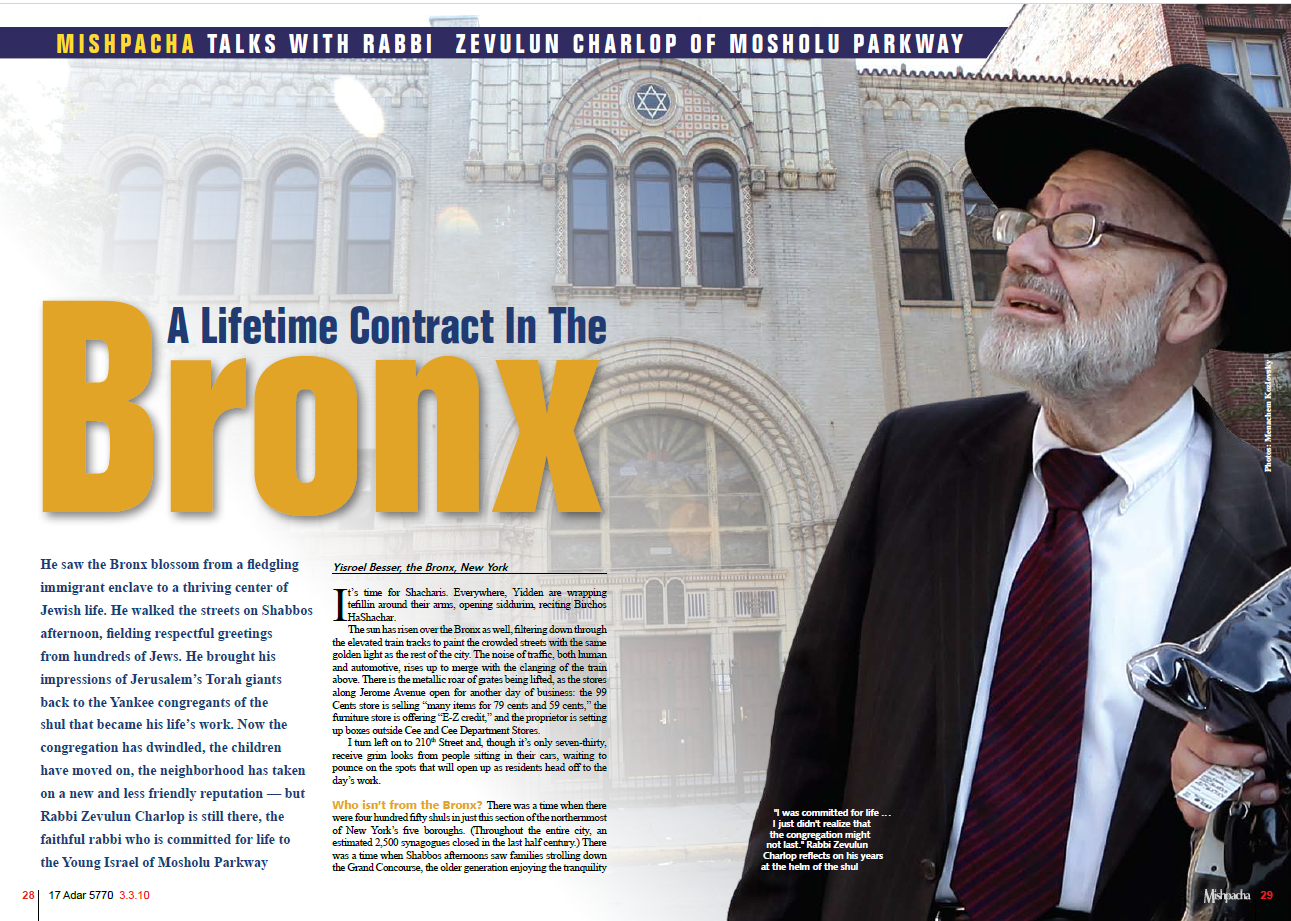

He saw the Bronx blossom from a fledgling immigrant enclave to a thriving center of Jewish life. He walked the streets on Shabbos afternoon, fielding respectful greetings from hundreds of Jews. He brought his impressions of Jerusalem’s Torah giants back to the Yankee congregants of the shul that became his life’s work. Now the congregation has dwindled, the children have moved on, the neighborhood has taken on a new and less friendly reputation – but Rabbi Zevulun Charlop is still there, the faithful rabbi who is committed for life to the Young Israel of Mosholu Parkway

It’s time for Shacharis. Everywhere, Yidden are wrapping tefillin around their arms, opening siddurim, reciting Birchos HaShachar.

The sun has risen over the Bronx as well, filtering down through the elevated train tracks to paint the crowded streets with the same golden light as the rest of the city. The noise of traffic, both human and automotive, rises up to merge with the clanging of the train above. There is the metallic roar of grates being lifted, as the stores along Jerome Avenue open for another day of business: the 99 Cents store is selling “many items for 79 cents and 59 cents,” the furniture store is offering “E-Z credit,” and the proprietor is setting up boxes outside Cee and Cee Department Stores.

I turn left on to 210th Street and, though it’s only seven-thirty, receive grim looks from people sitting in their cars, waiting to pounce on the spots that will open up as people head off to the day’s work.

Who isn’t from the Bronx?

There was a time when there were four hundred fifty shuls in just this section of the northernmost of New York’s five boroughs. (Throughout the entire borough, an estimated 2,500 synagogues closed in the last half century.) There was a time when Shabbos afternoons saw families strolling down the Grand Concourse, the older generation enjoying the tranquility of a walk down a street that had never seen a pogrom or beating, while the younger generation looked confidently at this new land, America, ready to make it theirs.

But alas, the hundreds of thousands of Bronx Yidden — 660,000 in 1948 — have left the neighborhood, and many have left This World. Only the vaguest echo of their footsteps is heard. The shuls have been swallowed up by community centers, hospitals, flea markets, and, all too often, houses of other worship.

Gone as well are the places of Jewish culture, theaters and cafes that symbolized Jewish identity for those who had already left religious observance back in Russia. Their places have been taken by missions and revivals and gospel groups.

Eight miles into the Bronx and past the ghosts of four hundred fifty shuls, I pull up in front of one of the last remaining two shuls, beckoning Yidden for its morning minyan. [YB— About a mile north of the shul is one other shul, the Van Cortlandt Jewish Center. Other than these two, outside of the flourishing neighborhood of Riverdale, there are no other shuls in the Bronx.]

Young Israel of Mosholu Parkway, the shul that has seen them all come and go. Today, I have come to daven here, at the invitation of the man at its helm, Rabbi Zevulun Charlop.

The Only Jews Left

I enter the building timidly, feeling a rich and sacred history wash over me. One can imagine the lobby thronged with worshippers, the bulletin board covered in notices about the rabbi’s classes and sisterhood meetings. Now, the lobby is silent, the wall bare of posters. I enter the main sanctuary. A few men sit scattered throughout the large room, unwilling to forsake their traditional places, even at the expense of having to conduct conversations with people nine feet away. An elderly man sits with his arm draped over the bench behind him, facing a friend several rows back. There is an easy familiarity to their conversation, the intimacy borne of decades of habit, two chess pieces standing on an empty board.

Heads turn as I enter. Surely, I am not the first stranger to come join the minyan at the Young Israel of Mosholu Parkway. A sweet Jew named Leo is the first to welcome me, his suspicious glances switching to warm acceptance after he discerns that I am neither a criminal nor a curiosity seeker. (Well, not that kind, anyhow.)

He hands me a siddur and beckons to the empty seats all around.

I join the men in prayer, as Leo leads. (He used to learn in Torah Vodaath, he tells me, and he is comfortable at the amud.)

In the front of the room sits the rabbi, davening slowly, carefully, still wrapped in his tallis long after Shacharis is over, a lone figure swaying in prayer.

I take advantage of the few minutes of post-Shacharis banter to engage the men in conversation. Leo tells me that he really isn’t a native; he only moved to the Bronx when he married his second wife, a local. When he moved here, all the tenants in his building were Jewish, but now he and his wife are the only Jews left.

Stuart, another congregant, lives in the neighborhood. He works for the city and is an unfailing regular at the morning minyan. Later, the rabbi will tell me with paternal nachas of Stuart’s tzidkus. He had been on the fast track to success as an actor and comedian, and was featured on America’s most prominent television shows, but he gave it all up when he returned to religious observance and became an ehrliche Yid. “He is, without exaggeration, a tzaddik,” says the rav. A tzaddik serving his King in the solitude of North Bronx.

A sweet fellow explains to me that he really isn’t from the Bronx at all. “I came from Eretz Yisrael ten years ago to stay with my ailing mother, and I’m still here. She passed away, and I’m planning to return any day now.”

“Yes, any day now,” one of the old-timers rolls his eyes good-naturedly.

There is a sense that this conversation, down to the line, is repeated every time there is a new audience.

Leo is telling me how he experienced a major accident involving a faulty elevator in his building and was nearly killed. “I was in the hospital for weeks, and the story was on television and everything. It’s a miracle that I’m alive.”

“Yeah,” cackles another fellow, “that’s why we all put up with him, because he’s going to sue the landlord and fly the whole shul down to Palm Beach with the money he gets.”

The rabbi is done davening and he approaches. There is a gentle hush in conversation, a moment of respect for a beloved and devoted mentor.

“Good morning, rabbi.”

The gentle rabbi greets each by name, asking this one about his granddaughter’s bar exam, and another about his doctor’s appointment; while a third, a Bronx native named Davis — an African-American in the process of converting — shoves a Tanach in front of the rabbi, and asks about a discrepancy in the translation of the Targum between Sefer Yoel and Yishayahu.

The rabbi smiles at me. “You gotta be prepared for everyone,” he says.

A Shul to be Proud Of

Later on, I spend some time in the sanctuary with the rabbi, as photographer Menachem Kozlovsky photographs the encounter.

Rabbi Charlop speaks softly, humbly, opting to use the word “we” rather than “I,” as if it were the shul that gets the credit. “When we built this place, we were the first shul in the Bronx in about thirty-five years to have an ezras nashim, a ladies’ balcony. It was the late fifties, and most of the local shuls were doing away with mechitzos altogether. Yet we went and did it the old-fashioned way. But at the same time, we were the first to have air-conditioning. We wanted people to have positive associations with Yiddishkeit.”

The stained-glass windows are magnificent. I had heard that they were designed by the rabbi himself and executed by the same firm that produced the Chagall window at the United Nations. He smiles when I ask him to verify that rumor. “We wanted a shul that people would be proud of.”

The rabbi asks Menachem, our photographer, not to photograph the parts of the shul affected by the leak. There is an unsightly watermark where water from a burst pipe seeped down from the ladies’ section, down the wall of the shul, lifting the carpet and then continuing into the basement, where it did further damage. There really isn’t a single inch of the shul that was unaffected by it.

It bothers the rabbi that his shul doesn’t look as it should, and for the past several years, the shul has been fighting its insurance company, which refuses to pay out the five hundred thousand dollars necessary to repair the damage. The shul has a part-time secretary — three half days a week — and a board of directors who work alongside the rabbi. The rabbi mentions Mr. Irwin Cohen, who plays a central role in keeping the shul alive.

“The insurance company didn’t want to pay, because they think we caused the flood in order to collect the payment. That’s par for the neighborhood. Only recently have they made partial restitution, but far less than the repairs require.”

Priceless Recollections

The shul is only part of Rabbi Charlop’s story. He fleshes out the tale as we drive up and down the streets around Mosholu Parkway and the Grand Concourse, the streets where Rabbi Zevulun Charlop has been greeted as “the rabbi” for over half a century.

The recollections that fall from his lips are priceless. It is clear that he is keeping back much more than he is saying. Some of the buildings still bear the stamps of Jewish life, the Magen David or Hebrew letters poorly painted over. He shows us the grandiose shuls of another world. “That’s the Mosholu Jewish Center; the rabbi there was the eminent Rabbi Herschel Schecter. At least fifteen years have passed since it closed down, and two other major centers closed before that.”

We pass the Sholom Aleichem Cultural Center and the rabbi is almost whispering. “We have had several important baalei teshuvah from there.”

He points to a shop. “Here was the tailor, an old European fellow who knew Bava Kama by heart, every word. He was open on Shabbos.”

We pass by a large church and the rabbi laughs, as if to himself. I urge him to share the story behind his smile.

“This is a Catholic church and school run by nuns. They hired a new priest here, and it was considered a major appointment in our neighborhood. I was surprised when two sisters in their religious habits came to my office at the shul and asked me if I would participate in the installation of the new pastor. ‘It would be a wonderful ecumenical gesture. You would be the first rabbi to participate in the induction of a new pastor,’ they said. I didn’t want to rebuff them out of hand, and I told them that I couldn’t accept their much-appreciated invitation as I would be in California on that day.

“As it turned out, several weeks later, I received an invitation to a family wedding in Pittsburgh for that very day, so I had to be out of town in any event. My wife, the tzadeikes, insisted that, immediately following the chuppah, I fly to California. ‘It will be a chillul Hashem if you don’t go.’ She forced me to go, so I took a flight to California, landed, and turned around for the return flight on the red-eye. My wife was worried about chillul Hashem and even more so, sheker.”

He shows me a rather large home where a young chassidishe rebbe started his ‘rebbestive.’ His name was Rabbi Rosenbaum, and his congregation was located around the corner from the Young Israel. “Here, the Mosholu Rebbe lived.”

Rabbi Charlop remembers when the Rebbe, just twenty-one at the time, came to the neighborhood; he delivered an address at the kabbalas panim. “His wife soon organized a playgroup for small children. They were lovely people, and he opened this little shtiebel. He had trouble gathering a minyan, so I always sent him our people. Some of my balebatim weren’t pleased that I was strengthening a potential competitor, but what could I do? He was an ehrliche Yid and a talmid chacham.”

Again, the soft laugh. “Today people think that Mosholu is a town in Europe. They don’t know that the Chassidus started here, in this building. Baruch Hashem, it did much better in Brooklyn.”

There were two other chassidishe shtieblach that preceded the Young Israel. “In one of them, the rebbe was a Chernobyler einekel named Twerski.”

The rav grows emotional as we drive through the park. “Ah, was Shabbos something special here! So many Yidden! We would walk here, Friday night and Shabbos afternoon, my wife and I, and speak with Jewish people. So many baalei teshuvah, with children and grandchildren who are true yirei Shamayim, started their journey on these paths....”

A Jerusalemite Giant in the American Wilderness

Later on, I sit with Rabbi Charlop in his office at RIETS, where he has served as menahel, dean, and masmich for decades. Before that, he was a talmid at the yeshivah, where he earned his smichah. Though he takes special pride in having been a close talmid of Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, ztz”l, his first and foremost influence was his father, Rav Yechiel Michel Charlop.

“He was a gaon. As a child, I thought that all rabbanim don’t sleep, just sit and learn the whole night.”

Who was Reb Michel?

“He was a product of Yerushalayim. At sixteen, he was one of the promising young prodigies in a city filled with budding talmidei chachamim. At the time, Yerushalayim had a special kollel for iluyim, a select group, called Kollel L’Mitzuyanim at Yeshivas Ohel Moshe. The kollel, which included many luminaries, had been formed by Rav Yitzchok Yeruchom Diskin with the specific goal of saving these future gedolim from starvation, and the members were provided with a basic stipend, enough for bread. My father, who was probably the youngest of the group, was designated by Rav Yitzchok Yeruchom to say chaburos to the likes of Rav Pinchas Epstein, Rav Amram Blau, and many others. Several of those shiurim have been preserved in Chof Yamim Sefer HaZikaron, which was published after his petirah.

“But the poverty and hunger were oppressive, and my father went to learn across the ocean, in America. He received smichah from Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan, which was located at the time on the East Side of New York, and assumed his first rabbinical position in a shul called Anshei Volozhin, noted for the many talmidei chachamim who davened there.”

From New York, Rav Michel was asked to serve as rabbi of Canton, Ohio. From Canton, he was invited to become the rav of Omaha, Nebraska.

Rabbi Charlop recounts, “At the time, there was a great talmid chacham in that city named Rav Grodzenski, a cousin of Reb Chaim Ozer. Before my father got the position, he had to spend a few days at the home of this rav, as kind of an interview. He passed and got the job.

“In 1923, my father became the rav of the four Orthodox shuls of Omaha with the express understanding that he would not enter the three of them whose mechitzos were not in order. He arrived for Rosh HaShanah, and by Shemini Atzeres, all of them had proper mechitzos.”

The path of American rabbanus was a lonely one, and it led the young family through Canton and Omaha before ending in the Bronx. “My father always had his friends; the seforim that surrounded him. Also, these towns were filled with Yidden in those years, with Yiddish as the predominant language, and the memory of the shtetl still ingrained in them. And there were often guests from Jerusalem and Europe who would come collect money. Many stayed in our home.”

Rabbi Charlop tells of one particular guest. “The Torah Temimah, Rav Boruch Epstein, came to Omaha and stayed with my parents for six weeks. My father took him to both of the Kansas Citys — in Missouri and Kansas — and Lincoln and York, Nebraska, to sell his seforim, principally his Baruch She’amar on tefillah. Even the Yidden who had settled out there knew of him: some people gave him a dollar, while others gave him hundreds of dollars.

“Though I have no recollection, I grew up with the story how he shared a room with me when I was in toddler in the Bronx. He was a cousin of my mother, whose maiden name was Shachor; they were a nephew and a niece of the Netziv. In fact, every Erev Shabbos my mother would light candles on a leichter passed down from the Netziv’s sister.”

When the family moved to the Bronx, Reb Michel assumed the leadership of the Bronx Jewish Center, a shul with over a thousand members. Yet the burdens of the rabbinate never took him away from his true love. Hour after hour, night after night, he sat there learning, writing, singing to himself.

It is remarkable that a rav in the America of the 1920s and 1930s, an era when stronger men were broken by the pressure tactics of butchers and meat purveyors, managed to remain immersed in learning. Yet he succeeded. The third volume of his sefer Chof Yamim boasts correspondence with a virtual Who’s Who of the Torah world: Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, Rav Nissan Telushkin, Rav Isaac Liebes, Rav Mordechai Mann, Rav Isser Yehuda Unterman, and Rav Shmuel Boruch Werner (a rosh beis din in Tel Aviv and brother-in-law of Rav Charlop). The lengthy teshuvah of a young Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach and Reb Michel’s response constitute the longest siman in the sefer with thirty-seven seifim.

“There is a letter from Rav Michel Yehudah Lefkowitz on behalf of the Chazon Ish. Rav Michel Yehudah shared with me how the Chazon Ish received my father’s sefer — chelek rishon of Chof Yamim — which refers to the sefer Chazon Ish several times, with extensive ha’aros on the sefer. The Chazon Ish was then at the end of his life and very weak, but he told Reb Michel Yehudah, ‘A rav in the Bronx who is able to write this way, so alive in the sugya, deserves an answer.’ So Reb Michel Yehudah followed his rebbi’s instructions and penned a reply to each of the five ha’aros my father wrote, any time my father referred to the Torah of his rebbi, in addition to his own ha’aros. This is included in Chof Yamim, chelek shlishi.”

“The pressure on you must have been tremendous,” I remark to Rabbi Charlop, who was an only child of an extraordinary gaon. He smiles. “Absolutely. My father expected me to keep his hours and pace, and would always say ‘bei mir vet ihr kein ben yochid’l nisht zein,’ here we won’t allow you to be a pampered ‘ben yochid’l.”

When Zevulun was nineteen, his father decided that it was time. He was going to Eretz Yisrael to meet the zeideh, the famed tzaddik, mekubal, and gaon, Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlop.

Visit of a Lifetime

It’s not just his voice. There is an expression of acute longing on the rabbi’s face as he recalls “the visit.” His voice trembles as he crosses decades, continents, and takes me to a world that was.

It was 1949. Young Zevulun Charlop was accompanied by his mother on the journey to meet the revered zeideh, in a sense, a journey back in time for the young American student.

“We were met at the Haifa port by my mother’s brother, Reb Moshe Leib Shachor, one of the gaonim of Jerusalem and the author of Avnei Shoham and Bigdei Kehuna, who had been traveling all day. It took us a full six hours to reach Jerusalem, switching from bus to bus. But when we finally reached Shaarei Chesed, where my zeideh’s yeshivah, Beis Zvul, was (and still is) located, I forgot all the exhaustion. The street was filled with people. It seemed that the whole shtetl, perhaps a hundred people, had come to see the ‘einekel from America,’ Reb Michel’s son.”

As he approached the zeideh’s house, there was a hush among the crowd. Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlop was coming down the stairs, wearing his white and gold-lined Shabbos bekeshe and crowned with his shtreimel. The frail man looked at his grandson and as he did, he recited the brachah of Shehecheyanu with sheim umalchus.

“It was a visit that lasted eight weeks, and through it all, I had one item on my agenda. The first morning, I sat down to learn with my zeideh, and he handed me a notebook and we started Masechta Makkos. I would write down his kushyos and teirutzim, as well as my own ideas. He had this way of turning everything that I would suggest into a chiddush. ‘You probably mean to ask as such,’ he would say, turning my youthful suggestions into penetrating insights.”

Rabbi Charlop takes a moment to describe the breadth of his grandfather’s knowledge. “This was a man who was fluent in the entire Shas, a scholar, a mystic who was familiar with the entire corpus of halachah, aggadah, and sod. A person who had a private session in Kabbalah with the Gerrer Rebbe, the Beis Yisroel, before his father, the Imrei Emes, passed away and he was appointed Rebbe. Rav Yitzchok Hutner told my cousin, Rav Ephraim Charlop, that it was my zeideh who opened the seforim of the Marahal before him, in private chaburos that he gave. Yet he sat with me, his American einekel, and made me feel that my kushyos were exceptional, my teirutzim brilliant.”

The rabbi shares a magnificent story that underscores the sensitivity of the great man. “One of the gedolei Lita lived in the neighborhood, Shaarei Chesed, and my zeideh would usually walk him to shul. This man was a tremendous talmid chacham and posek, and would be surrounded by a small crowd of people asking him halachic questions. He would murmur the answers quietly, but wasn’t very clear, so my zeideh took the job of explaining the answers of this gadol to the people. This was a daily occurrence, and it surprised me.

“Only later did I learn what was really going on, why the zeideh was so anxious to accompany this distinguished Jew to and from shul and be there to explain his answers. This gadol was, Rachmana litzlan, suffering from the first stages of Alzheimer’s, but at the time, no one knew it. He was confused, and his answers were ambiguous. The zeideh was fiercely protective over the kavod of this great man and thus, did his best to cover up the condition.”

Being exposed to the gedolei Yisrael in the Holy City was a seminal experience for the Bronx boy. “My uncle Moshe Leib Shachor’s backyard faced the home of Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, the rav and raavad of the Holy City. The early part of the evening, his whole house was lit up, with people coming and going. But as night progressed, the lights were turned off, one at a time. Then the whole house would be dark, and all you could see was the rav’s tall form framed by the window, swaying at his shtender late into the night.

“I told my zeideh about Rav Tzvi Pesach and he commented. ‘Your father also used to be that way. He would be fully dressed in the morning from the night before. So engrossed was he in learning that he never went to sleep.’

“‘He still does that!’ I protested fiercely.

“A strange look crossed my zeideh’s face, puzzlement mixed with pride. ‘Really? I wonder how come he never writes me letters of chiddushei Torah? Could it be that, chas v’chalilah, his tirdos, preoccupations, could have lessened the intensity of his learning? I heard from Rav Isser Zalman that he had received a letter from your father filled with brilliant ha’aros on Even HaEzel, so I was unsure. [YB—Rav Isser Zalman actually responded to those ha’aros with a kontres. Rav Shneur Kotler told Rav Charlop that he is unaware of any other “personal kontres” that his grandfather wrote.] You say he is still accustomed to learning throughout the night?’

“I assured my grandfather — who himself would learn with his feet in basins of cold water, and a sharp fluorescent light directly over his head, to prevent him from falling asleep — that it was so. He was happy.”

Rabbi Charlop recalls the sleeping habits of his grandfather, Rav Yaakov Moshe. “He slept on a plain board, covered by a sheet — with no mattress. One day, he wasn’t feeling well, and Dr. Zondek (the famed doctor who also ministered to the Brisker Rav) came to check him. He told my mother that it was absolutely imperative that the zeideh start sleeping with a proper mattress. That day, in the Jerusalem of 1949, my mother somehow found a store that sold good mattresses, and had one delivered to my grandfather’s home. We think it was the first time that he ever slept on a mattress.”

On that visit, Zevulun and his mother went to visit the Brisker Rav, a meeting initiated by the rav and which lasted more than two hours. The rav rose to his feet when they entered, saying “eishes chaver k’chaver.” When the American asked the rav for a brachah for hatzlachah in learning, the rav replied, “What you need to do is learn with hasmadah. If you do, then you don’t need the brachah, and if you don’t, the brachah won’t help.”

Recalls the rabbi, “When I repeated his words to the zeideh, he was extremely disappointed. He indicated that there were Rishonim and Acharonim who hold that tefillah would help for such requests.”

Forging Leadership

Rabbi Zevulun Charlop graduated Yeshiva University and received his smichah in 1954 from Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan. It was difficult then to get a position in a “kosher shul,” as the phrase went. The pressure to compromise on a mechitzah was tremendous, but the young Rabbi Charlop refused to consider such a position.

The Bronx was a hub of New York City’s Jewish community at the time, and the young Rabbi Charlop and his rebbetzin were offered the job to come lead the recently created Young Israel of Mosholu Parkway, which met in a rented two-family house. The prime advantage of the position was that it was in Bronx, so he could remain local. He married his new rebbetzin just three months after assuming the position.

It was a job that kept the young rabbi busy. “In addition to being the rabbi, I taught the four grades at our Talmud Torah. We couldn’t afford a secretary, and my rebbetzin and I would print up signs for the nightly classes on cardboard. Who had money? I barely had enough to live on, but there were more precious rewards. I was close to my parents and able to learn with my father every day, so I was happy.”

There were two figures responsible for taking Zevulun Charlop from a quiet position in the rabbinate to the deanship of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, where he would serve as teacher and guide to generations of young rabbis.

“On Shabbos, our shul would have many guests who were in the neighborhood because of the nearby Montefiore Medical Center, usually family members of patients. Owing to my wife, our home was wide open. She would cook in abundance and my children learned how to sleep on the floor. They were taught hachnassas orchim in the most practical of ways.”

There was a precious Jew named Abe Stern whose mother was a patient at Montefiore. He would spend Shabbos at the shul and that Charlop home, and became a lifelong friend of the rabbi. Abe Stern was active in the nascent kiruv movement, and among his kiruv strategies, he would organize summertime tours to Europe and Israel for Jewish teenagers. He insisted that Rabbi Charlop serve as the tour leader.

“I did not feel that I was qualified to meet the challenges, but he was very persistent. He would call my wife each week, unbeknownst to me, and say, ‘Don’t hold your husband back.’ In fact, she never did hold me back. In the end, she prodded me to accept.”

And, of course, most importantly, at the same time, Dr. Samuel Belkin, the rosh yeshivah and president of Yeshiva University, heard Rabbi Charlop speak at a dinner, and decided that he wanted the young talent to join his staff. It was a dinner celebrating the shul’s tenth anniversary, and the event at which the young rabbi was presented with a lifetime contract. Dr. Belkin knew that this was someone he wanted on his staff, but that wasn’t enough to convince Rabbi Charlop. “He was persistent, but I simply lacked the ambition,” Rabbi Charlop reflects.

Then Abe Stern returned from the tour, which he had convinced Rabbi Charlop to lead. He told Dr. Belkin of Rabbi Charlop’s ability to connect with youth, of a teaching voice that was traditional even as it was fresh and innovative.

Dr. Belkin approached Rabbi Charlop again, this time with new resolve. He offered the rabbi a position teaching Torah at RIETS. For five years, the rabbi taught Torah, in addition to a course in American history at the college level.

Five years later, just a few days before the new zman, Dr. Belkin approached Rabbi Charlop and said that, after discussion with Rav Soloveitchik, they had agreed to appoint him menahel of the yeshivah. “We put our trust in you.”

“What will be with the shul?” asked the rabbi.

“They will find someone else.”

Then, as now, Rabbi Charlop said no thanks, he was committed to his congregants and could not do that to them. “Okay,” said the president, “you will teach this year and keep your job and we will revisit this discussion next year.”

Rabbi Charlop states the obvious with his trademark soft laugh. “We haven’t gotten to do that yet.”

In 1962, the shul, Young Israel of Mosholu Parkway, started construction on a magnificent new building. The neighborhood was flourishing, and many of the Jewish doctors at Montefiore lived nearby and davened there. At one point, there were forty-four shomer Shabbos doctors who davened in the shul.

Soon enough Rabbi Charlop had a beautiful new shul, a flourishing congregation, and a lifetime contract.

“I didn’t realize that they didn’t have a lifetime contract,” he says ruefully.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the shul thrived, with a full sanctuary and overflow minyan on the Yamim Noraim. 1978 was the first year that there was a decrease in congregants. In 1983, the second minyan was unnecessary, and the decline has been steady ever since. At present, the weekday Shacharis minyan is shaky, and even Shabbos is sometimes a question. The rabbi himself is one of only two white residents left in his building, and on Shabbos, he often hosts guests who would otherwise eat alone.

Undeterred

So why does he remain, the good rabbi? His children have, baruch Hashem, assumed fine rabbinical posts across America and Israel, and he is welcomed with respect and reverence wherever he goes. His talmidim fill a great number of the rabbinic posts in synagogues across the country, presiding over full shuls and burgeoning communities, yet he remains there, in the same place he started.

Perhaps the answer lies in the vacant shul.

In muted letters, the dedication on the aron kodesh reads “In memory of the child, Yaakov Moshe Charlop,” an eternal monument to the rav’s young son who passed away at age three from illness over forty years ago.

On Shabbos, there is a sense that he’s there, sitting next to his father.

In another corner of the shul is a faded wooden shtender. “Here, the great gaon Rav Yechiel Michel Charlop studied Torah,” proclaims a small plaque.

“At the end of his life, my father and mother came to live in our community, but my father insisted on walking back to his shul for davening on Shabbos, a distance of over an hour, and then of course, he would walk back. He was elderly, and the walk was a rough one: neighborhood ruffians would curse and throw stones at him, yet he remained undeterred. Maybe there would be a minyan. He was the rav, and he had to be there.”

Like father, like son. Is it any wonder that Rabbi Zevulun Charlop has chosen to stay in the Bronx? There is a minyan and he is the rav.

(Originally Featured in Mishpacha Issue 299)

Oops! We could not locate your form.