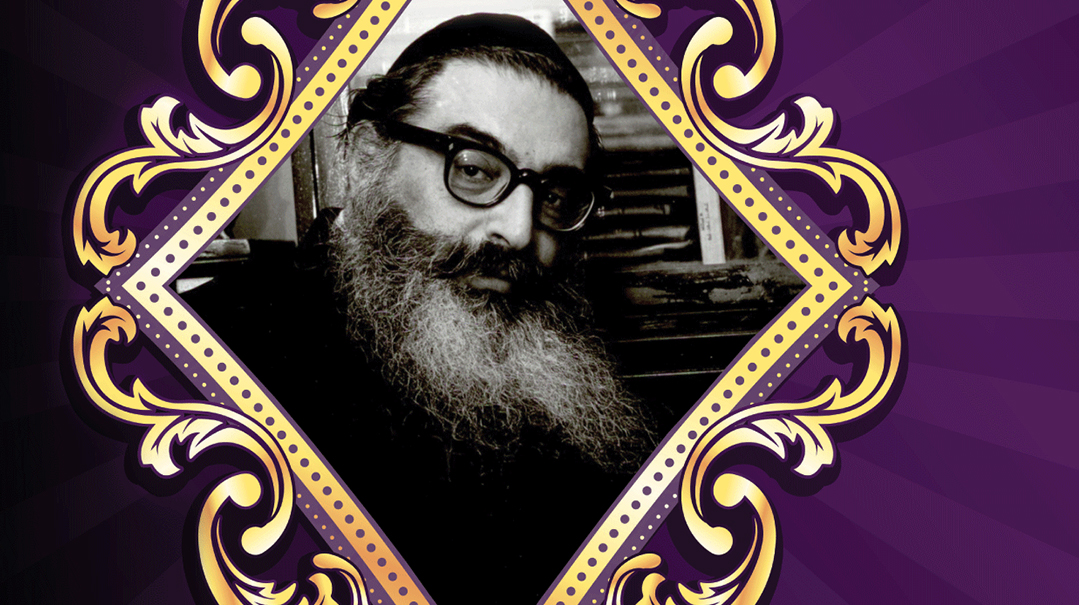

A Life Of Majesty And Mystery: An Appreciation of Rav Yitzchok Hutner

| November 24, 2010That concern for his students’ spiritual welfare spurred the Rosh Yeshivah to spare us no criticism when he felt we needed it

Thirty years are not enough.

Chazal tell us that a person does not begin to understand his rebbi until forty years have passed (Avodah Zarah 5b; see Rashi, Devarim 29:6). But thirty years is sufficient for what his son-in-law and revered successor, Rav Yonasan David, shlita, currently rosh yeshivah, refers to as “the yearnings” for Rav Yitzchok Hutner’s guidance, Torah, and radiance (see introduction to Pachad Yitzchok, Igros). The following appreciation is neither definitive nor conclusive. It is simply one talmid’s yearning for a rebbi who uplifted his generation, rejuvenated the study of hashkafah, defined world events and cosmic issues from a Torah perspective, while never losing sight of the individual’s needs, concerns, and private battles.

Some of the stories are my own experiences, others were shared by gedolei talmidav, his closest disciples. None are simply rumor or hearsay. He was skeptical of outlandish anecdotes, punctilious about the ones he himself related, and would not have been pleased with blind hagiography. However, in the past three decades, the Rosh Yeshivah’s influence has grown exponentially. Seforim, books, scholarly articles, and countless lectures have attempted to explicate the vast treasure he left behind in the multiple volumes of his magnum opus Pachad Yitzchok.

I once brought to his attention a translation of one of the maamorim (essays) in Pachad Yitzchok that appeared in a journal; the translator had made some hopeless mistakes and misunderstood Rav Hutner’s meaning. The Rosh Yeshivah laughed and bellowed, “Loz em leben — leave him alone. I am happy that people in his circles will be motivated to open a Pachad Yitzchok.”

The Rosh Yeshivah himself discovered the “mysterious” (his word) phenomenon that one sometimes gains more from a rebbi after he passes away. In a letter he wrote at the age of twenty-one to Rav Isaac Scher, ztz”l, he confesses that “ideas and concepts that he [the Alter of Slabodka] desperately tried to explain to me, but that I was unable to understand, suddenly were clarified to me with his passing. The righteous are greater in death than in life” (Pachad Yitzchok, hereafter PY, Igros, page 251 and 253).

It is my hope that we, too, can gain even more from the Rosh Yeshivah now than when we were fortunate to have him with us in life.

The Prince

His own rebbi, the Alter of Slabodka, defined him best. The barely adolescent Yitzchok Hutner arrived in Slabodka at the tender age of fourteen and was almost immediately invited into the Alter’s inner circle. The older, veteran talmidim were afraid that the new student would require the Alter to lower the level of his mussar talks or diminish the lofty standards to which they were accustomed. Young Meir Chodosh, future mashgiach and baal mussar, allowed himself to bring this to the Alter’s attention. “Don’t you see?” the Alter reassured them. “He is a prince!” (The Mashgiach Reb Meir, page 112.)

He was a prince at fourteen and he maintained that royalty throughout an incredibly productive and majestic life. That nobility manifested itself in many ways at the yeshivah he later founded, Mesivta Rabbi Chaim Berlin. I remember, as do most of my contemporaries, the trepidation I felt when I was about to ring his doorbell or the buzzer to his office. Indeed pachad — abject terror — was the operative word for most encounters with the Rosh Yeshivah. But that moment of apprehension often turned into life-changing moments of revelation. The Rosh Yeshivah, sometimes gently, sometimes searingly, tore off the veneers obscuring our souls and helped us discover our inner identities. Although the awe remained forever, for those of us privileged to remain in his presence, pachad ultimately mingled with an ethereal joy at his fatherly interest and involvement in our every tribulation and success.

I first had the zchus of meeting the Rosh Yeshivah when I was still in high school. I attended Mesivta of Eastern Parkway, an offshoot of Chaim Berlin whose menahel was the beloved Rav Elimelech Silber, ztz”l, and whose rosh mesivta was the charismatic Rav Mordechai Weinberg, ztz”l. Both Rav Silber and Rav Weinberg consulted often with the Rosh Yeshivah, and the Rosh Yeshivah favored the Mesivta with a full original maamar when it began (printed in Igros, page 134).

Reb Mottel, as he was lovingly called by all, sent a few of us to say “ah shtickel Torah” to the Rosh Yeshivah. We were terrified. After I finished my pilpul, the Rosh Yeshivah interrogated me about my family, background, and aspirations. I practically forgot my name. When I told him my parents were survivors, he visibly softened his tone and shared words of encouragement.

After that, my bond to the Rosh Yeshivah grew ever deeper and multifaceted, to the point where if I missed a maamar, he would call me in for reproof, while subtly checking to see if everything was in order at home. I left his home or office feeling that he not only cared deeply about me, but that there was nothing in the world more important to him than my physical and spiritual welfare.

That concern for his students’ spiritual welfare spurred the Rosh Yeshivah to spare us no criticism when he felt we needed it. In keeping with his mastery of language, he would always administer the reproach with an unforgettable turn of phrase.

A student who was prone to spiritual extremes decided to adopt an immoderate stringency upon himself concerning eating. When he asked the Rosh Yeshivah’s opinion of the stringency, Rav Hutner’s response was, “I always thought that religion concerns itself more with what comes out of a person’s mouth than what goes into it.”

As the great mashgiach Rav Shlomo Wolbe, ztz”l, wrote of him, “Rav Hutner was unique in his generation in the breadth of his understanding of nigleh [the revealed part of the Torah], nistar [the hidden portion], his understanding of all branches of knowledge, and the incredible depth of his wisdom” (Igros U’Kesavim I, page 199). This has perhaps become somewhat known over the past three decades. However, what he hid, and is almost unknown, is how he was able to access his profound insight into individuals, in order to improve their lives and alter their trajectories away from what could have become their declines and failures.

A brilliant young man applied to the Chaim Berlin Kollel, only to be rejected by the Rosh Yeshivah, to the surprise of all. The Rosh Yeshivah advised him to become a rebbi in the morning instead. Seven years later the true story emerged.

This talmid had a serious speech defect and was difficult to understand. The Rosh Yeshivah had summoned a speech therapist and told him to converse casually with the young man in Camp Morris (the Yeshivah’s summer location), under nonthreatening conditions. The therapist’s diagnosis was that the student had a progressively debilitating condition that would inevitably leave him with a lifetime defect. The only regimen that would save him was a daily stint of public speaking, lasting several hours.

The Rosh Yeshivah knew the young man, and concluded that he would not accept this solution if presented therapeutically. Yet a teaching job (which was not precluded by his disability) would force him to speak in public. When he was finally cured and became well-known as an articulate and eloquent rebbi, the Rosh Yeshivah allowed the truth to emerge. The young man, now well-spoken, confirmed the Rosh Yeshivah’s assessment and was profoundly grateful for his intervention.

Sometimes a seemingly casual comment revealed a profoundly deeper spiritual agenda. One Rosh HaShanah the Rosh Yeshivah called in a top bochur and made an unusual request for such a day.

“I just passed by the dormitory and so-and-so seems lonely. Take him for a walk.”

“But Rebbi, today is Rosh HaShanah,” the bochur mildly protested, clearly implying that he had better things to do.

The Rosh Yeshivah responded with an epigram the young man would never forget: “The one who is satiated never understands the hunger pangs of the one who is starving.”

Needless to say, the Rosh Yeshivah saved one boy from possible depression that day, while another got an early start on a successful life of helping others.

The deeper spiritual agenda alluded to may be the Rosh Yeshivah’s first maamar in the Pachad Yitzchok on Rosh HaShanah. Nechemiah is exhorting the newly returned exiles from Babylonia to properly commemorate the upcoming New Year. “Go, eat rich foods and drink sweet beverages, and send portions to those who have not prepared…”(Nechemiah 8:10).

The Rosh Yeshivah alerts us to the anomaly of sending what later came to be called “shalach manos” on Rosh HaShanah. What do acts of chesed have to do with Rosh HaShanah? In an elaborate and closely reasoned maamar, the Rosh Yeshivah illuminates for us the day of Rosh HaShanah in a new light.

Since Rosh HaShanah is the day of Man’s creation (zeh hayom techilas maasecha) and Hashem created the world as a vehicle for His loving-kindness (olam chesed yibaneh — Tehillim 89:3), it is only natural that this day become suffused with acts of chesed. The Rosh Yeshivah demonstrates brilliantly and irrefutably that, unlike other middos, chesed relates to creation itself as much as to later acts of kindness. Therefore, it is both appropriate and even inexorable that chesed be a part of the day of Man’s creation.

To those who were privileged to even stand in his shadow, it was not far-fetched to understand his command to a student to perform an act of chesed on Rosh HaShanah as the fulfillment of a maamar in Pachad Yitzchok. To the Rosh Yeshivah, theory and action, hashkafah and halachah were inseparable and unified. And that spiritual harmony of his multifaceted persona is perhaps, most of all, what defined him (see Sefer HaZikaron, page 70).

An Extraordinary Synthesis

A few years ago, I stood at the banks of the Nieman River in Lithuania and tried to imagine the Rosh Yeshivah at fourteen crossing the bridge from Kovna into the universe of Slabodka. Surrounded by other geniuses such as Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, and Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, zichronam tzaddikim livrachah, the young Yitzchok Hutner learned from Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, ztz”l, the legendary Alter of Slabodka, to treat each student as the unique individual he was. Just as the Alter helped mold these and other future giants into gedolei Yisrael who each made a distinct contribution to Knesses Yisrael, Rav Hutner later did the same in his own right.

As he traveled through the Torah world of the early twentieth century, both physically and intellectually, Rav Hutner absorbed the best and most diverse of the approaches available in his day. Born in 1906, known from childhood as the Warsaw illui (prodigy), Rav Hutner absorbed the Alter’s endless wisdom from 1921 until 1927.

From 1925 to 1927, the Alter taught at the Hevron branch of Slabodka in Eretz Yisrael, and Rav Hutner followed him there, taking advantage of the opportunity to explore the gamut of gedolim available to him in Eretz Yisrael. These included a kaleidoscope of approaches to Torah, such as those of the centenarian Sephardic tzaddik Rav Shlomo Yitzchak Alfandari, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, and Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, zichronam tzaddikim livrachah.

Although he became extremely close to Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook, ztz”l, and absorbed many of his teachings, he vehemently rejected Rav Kook’s position on Zionism. He had already learned to filter genius and greatness, distilling what he concluded was right for his own development and character.

AHis paternal roots were Lithuanian, but maternally he was connected to the Gerrer shtiebel in Warsaw, where he picked up a touch of Kotsk and Ger, adding their rich legacies to the mussar molecules and Slabodkan atoms with which he was building his ever-deepening and unique personality.

After publishing his first halachic work, Toras HaNozir, in 1932, at the age of twenty-six, his name became known among the gedolim of the time as a future gaon and posek. The gadol hador, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky, effusively wrote that he was born to greatness, would surely become famous, and his words would be studied by multitudes. The D’var Avraham of Kovna called him a gaon and predicted that he would be a blessing to his people.

Much has been written over these past three decades about the so-called contradictions in the Rosh Yeshivah. Was he primarily a chassid or a Litvak, was he more intellectual or emotional, Maharalian or Gra, mussar or Ramchal? The answer, of course, is that he was the embodiment of an extraordinary synthesis, a systematic and seamless convergence of all these and many more influences and strains. Indeed, he often said of himself that, like Adam HaRishon, his earth had been gathered from many places (Sefer HaZikaron, page 79).

In fact, once when the Rosh Yeshivah perceived someone acting with pretensions and excessive humility, he informed him of a chassidic tradition.

“The Ruzhiner taught,” the Rosh Yeshivah archly informed the young man, “that the best place to hide something is where it will least be found, such as underground. Humility, too, should be buried under the earth of gaavah (arrogance).”

It was actually the Rosh Yeshivah’s magisterial grandeur which camouflaged a fundamental modesty in all things. From his earliest private writings, it was clear that what he would reveal was infinitesimal compared to that which remained hidden. And so, when Rav Aharon Schechter, shlita, currently revered rosh yeshivah, returned from the levayah thirty years ago, his first poignant public words were, “We did not know him; we will never fully know who he was.”

The Power of Language

From his earliest childhood letters, the Rosh Yeshivah was tremendously careful with his use of words, particularly in written form.

One of my most treasured although difficult experiences was translating his major statement on Churban Europa. The Rosh Yeshivah knew that it would be controversial, groundbreaking and emotional. I sat with Rabbi Chaim Feuerman’s original draft, rewriting according to the Rosh Yeshivah’s instructions and, with trembling hands, handed each page to the Rosh Yeshivah. He scanned the page, returning over and over to particular words, probing, demanding, suggesting alternative synonyms. Sometimes he would subject a key adjective or phrase to five minutes of rigorous parsing, until every nuance and possible connotation had been thoroughly exhausted.

So was I, but the Rosh Yeshivah continued for seven straight hours until he was satisfied that his intentions had been accurately conveyed. I had begun the session sick with a fever; by that time I probably did not present a pretty picture.

Suddenly, the Rosh Yeshivah looked at me sharply, asking, “Yainkel, vos iz mit dir? What is the matter with you?”

When I told him, he sent me out in mock anger and ordered me to go home to bed. After we had completed the article the next day, he rewarded me for my efforts by sharing a private vort that I have used for over four decades in numerous ways. When I asked him permission to relate the original to a wider audience, he shot me one of his sharp glances and quoted what the Chasam Sofer once warned one of his talmidim: “If you wish to say over my Torah in your name, by all means, but l’maan Hashem, don’t ever say over your Torah in my name.”

This incredible care with language manifested itself in daily speech as well. A bochur consulted with him about a proposed shidduch and he felt that the Rosh Yeshivah was against the suggestion.

“Should I say no?” the young man inquired.

“What?” the Rosh Yeshivah protested, “say no to a bas Yisrael?!”

Clearly, the issue was not so much about the decision as the proper terminology to be utilized about a Jewish neshamah.

On another occasion, the Rosh Yeshivah heard that a well-known rebbi was using the Talmudic terminology idis (best), beinonis (average) and ziburis (worst) — generally applied to delineate levels of real estate — to rank his talmidim. The Rosh Yeshivah inveighed vehemently to the rebbi about this linguistic abuse, and disabused the rebbi of continuing such appellations.

Perhaps he learned this sensitivity in Slabodka, from Rabbi Avrohom Grodzensky, the great mashgiach and author of Toras Avraham. The Rosh Yeshivah as a young bochur was speaking to the mashgiach, who had a pronounced limp. During the conversation, the young Rav Hutner forgot himself and utilized a metaphor concerning a chigeir, one who has problems walking. Rav Grodzensky signaled to the future Rosh Yeshivah that he needed to be more sensitive in his choice of language (Sefer HaZikaron, page 119).

Sometimes the Rosh Yeshivah utilized a sharp phrase to drive home a point. A certain bochur wanted to work in a hotel over Pesach to earn some cash. The Rosh Yeshivah’s assessment was that the bochur did not need the money that much and was being lax in his Yom Tov observance. He quoted to the bochur from “Chad gadya” at the end of the Haggadah: “d’zabin abba b’trei zuzei,” which is usually translated as “which father sold for two zuz.” The Rosh Yeshivah scolded the bochur with the innovative translation, “You have sold your Father for two dollars.” The words had their effect and the young man ultimately experienced the spiritually uplifting Yom Tov his soul required, going on to greater things later in life.

Rav Hutner’s phraseology was pitch-perfect, often conveying a profound change of status when we didn’t realize one had occurred. An older talmid, before leaving the yeshivah to begin his first professional position, first visited the Rosh Yeshivah for formal permission and a brachah.

“Until now, you were in my hands,” the Rosh Yeshivah intoned; “now I am in yours.”

A world of affinity, wisdom, caring, and realignment of relationship were poured into those pregnant words.

Perhaps the most dramatic story regarding the Rosh Yeshivah and language actually illustrates the conclusion that linguistic sensitivity is not always what it seems to be. The Rosh Yeshivah himself related the following astonishing anecdote:

“Once I was with the Alter of Slabodka and a distinguished group of people, including Rav Avraham Grodzensky, the Alter’s sons, and Rav Avraham Eliyahu Kaplan of Berlin. The Alter characteristically asked Rabbi Kaplan to recount a pleasing middah that he had witnessed in Berlin.

“Rabbi Kaplan recounted that the German language has a very refined phrase that bespeaks a sense of humility and subjugation to others. If someone was asked a question, he would not merely respond with an assertive answer. For instance, if someone asked, ‘Where is such-and-such a street,’ the respondent would say, ‘It is around the corner to the left; nicht wahr [not so]?’ Rabbi Kaplan explained that this was a subtle way of including the questioner in the answer; the respondent was indicating that he too, was unsure and needed corroboration from his interlocutor.

“When Rabbi Kaplan concluded, an argument broke out in the home of the Alter about this praise of the German language. Rav Avraham Grodzensky adamantly insisted that praising German in this way was forbidden under the prohibition of lo seichaneim — lo sitein lahem chein, that we are prohibited from finding favor in the non-Jewish ways (Avodah Zarah 20a). The Alter concurred. However, there was a strong-minded bochur present who defended Rabbi Kaplan’s position, asserting that there was nothing wrong in discovering a fine middah in a non-Jewish tongue and learning a lesson from it.

“Years later, I was sitting in my office preparing a shiur,” the Rosh Yeshivah continued in a particularly ominous tone, “when there was a knock at the door. A man, who surprisingly was wearing a coat on a very hot day, asked to speak with me, but I attempted to push him off until after the shiur. He persisted in his quest to meet with me immediately, since he needed to be on his way, and asked if I recognized him. I responded that I did indeed remember him as the bochur who had been present at the debate between the Alter and Rabbi Kaplan.

“The man suddenly removed his coat and showed me that he was missing an arm, and had a prosthesis in its place. He dramatically related that he had been a part of one of Mengele’s pain experiments. As the monstrous doctor was savagely amputating his arm, he had inquired, ‘It hurts, nicht wahr (does it not)? Ein Jude, nicht wahr – you are Jewish, is it not so?’

“The visitor continued, ‘You may remember, Rav Hutner, that I argued in favor of the refinement of the German language and what we can learn from its nuances. Now I realize that you are the only one left alive of those present at the Alter’s home, so I have come to ask mechilah for my foolishness and imprudence in arguing with my teachers.’”

The Rosh Yeshivah concluded that this story was a “mitzvah l’farseim” — it must be retold for the profound lesson it conveys.

Through Torah Eyes

The Rosh Yeshivah taught us to view every phenomenon through Torah eyes. Once, he remarked publicly on the inner motivation for suicide. Undoubtedly, the world propounds psychological, sociological, and emotional reasons for this heart-rending act. The Rosh Yeshivah, however, suggested that it stemmed from the fact that at creation, some angels said to G-d, “Do not create.” That negativism and nihilism embedded itself into the psyche of Man.

The Rosh Yeshivah taught us that everyone had both the right and mandate to be creative in Torah. In shiur the Rosh Yeshivah never imposed his opinions on anyone. One time a fiery argument broke out between the Rosh Yeshivah and one of the lions of the yeshivah, Rav Elya Weintraub, ztz”l. After a series of fierce skirmishes in these Torah wars, Reb Elya backed off and seemed to yield.

“Elya, come back,” the Rosh Yeshivah called out. “The Shemoneh Esrei says, ‘Return us, O Father, to Your Torah; restore us, O King, to Your Divine service.’ When it comes to Torah, there is no sovereignty. You are not obligated to accept my opinion.”

Despite the Rosh Yeshivah’s imposing demeanor and his calculated insistence on kavod haTorah, there was no elitism about him. The Rosh Yeshivah radiated love for every single Jew. One of his oft-repeated maxims was that one should not say, “I love so-and-so because he is humble,” or for some other good trait. Then you only love the trait, not the Jew. You must love a Jew simply because he is a descendent of Avraham Avinu. A dramatic example of this is actually a story within a story, often the best window into the recondite soul of the Rosh Yeshivah.

One of the Rosh Yeshivah’s veteran talmidim accompanied him to a bris in the Bronx. The taxi driver, an unaffiliated Jew, took one look at the Rosh Yeshivah and immediately put on his hat out of respect.

The Rosh Yeshivah commented to his traveling companion, “Who knows how much Olam HaBa this fellow has acquired with this seemingly insignificant act?” The Rosh Yeshivah then told one of his multitude of very carefully selected stories to illustrate a point.

One Erev Shabbos, the first Gerrer Rebbe, the Chiddushei HaRim, chose a particularly long route to the mikveh. When the shamash later asked about this mysterious route, the Rebbe answered, “On that street there are Jewish workers who are extremely simple people. Whenever I can, I try to provide them with opportunities that will bring them into Olam HaBa. When I walk by them, they say, ‘Here comes Reb Itche Meir!’ and they stand up and arrange their clothing [out of respect]. In this way, I help them enter into Olam HaBa.”

The Rosh Yeshivah, too, the great teacher of kavod haTorah, always had his eye out for the simple Jew and his needs as well. He could even derive some wisdom from a “Bowery bum.” One time, the Rosh Yeshivah and a few talmidim were walking down the Bowery, a street infested with derelicts at every corner. The Rosh Yeshivah, however, pointed to a strangely inspiring and uplifting scene. An inebriated fellow was slowly and unsteadily arising, his body besotted with the detritus of his tragic condition. Yet, as he stood up, despite all, he managed to set his hat straight upon his head and staggered off. An amusing scene to some; yet the Rosh Yeshivah saw in it hope for the eternal sense of kavod haAdam which is granted to every human being. This emphasis on the sanctity of tzuras haAdam and the fragility of Man’s tzelem Elokim was a theme throughout much of his writing and thought.

One of his pithy yet profound comments was that three had wreaked the greatest damage to tzuras haAdam: Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, and Sigmund Freud (Sefer HaZikaron, page 85).

The Rosh Yeshivah fulfilled in himself the mishnah “one should learn from everyone.” There was an out-of-town young orphan whose uncle brought him to the yeshivah to learn. This uncle, although a meagerly paid rebbi himself, always brought along a respectable check to the yeshivah when he came to visit .On one of his trips, he brought a particularly significant amount. When the Rosh Yeshivah inquired how he could afford what to him must have been an astronomical number, he answered, “A Jew must exert himself.”

The Rosh Yeshivah later related to the young orphan, “Do you know how highly I think of your uncle? Last Friday, I received an invitation from the rebbe of a local shtiebel, a tiny storefront operation, who did me a favor when I first arrived on these shores. He asked me to attend his Melaveh Malkah this Motzaei Shabbos. The truth is that I had just broken my leg, the snow was piled high and I was not feeling well. But all Shabbos, your uncle’s words would not leave me alone: A Jew must exert himself. Finally, after Shabbos I forced myself to go because of your uncle’s words.”

He left us an incredible lesson in parenting as well. When his only child, Rebbetzin Bruriah David, was born, the Rosh Yeshivah related that some of his closest friends gently kidded him about having a daughter and not a son. In a special diary which he devoted solely to his daughter and her chinuch, he wrote: “Every child born to parents constitutes a test. If they instill in that child the holiness of Jewish life, they have passed. Since we know that it is much harder to raise a daughter than a son in the holy ways of the Torah, I am overjoyed that of the tests, I have been granted the more difficult one.”

Perhaps the most astonishing and telling line in the diary that has been revealed to us is the Rosh Yeshivah’s promise to his daughter, “Bli neder (without promising), I will never leave you out of my thoughts for a moment.” How many of us could say such a thing, or perhaps even consider it? Yet, the Rosh Yeshivah and his rebbetzin, with this level of constant vigilance about their child’s chinuch, raised one of the premier mechanchos of our generation, who has herself, through her famous Machon Sarah Schenirer (also known as BJJ, an acronym for Beth Jacob of Jerusalem), already influenced several generations of nashim tzidkanios in Klal Yisrael.

Twin Pillars

The two pillars of Rav Hutner’s legacy, the creations into which he poured his very essence, were his primary works, the sefer Pachad Yitzchok; and his beloved yeshivah, in all its various divisions — Mesivta Yeshivah Rabbi Chaim Berlin, Kollel Gur Aryeh, and Yeshivas Pachad Yitzchok in Eretz Yisrael.

Unquestionably, one of the Rosh Yeshivah’s major eternal legacies is the published version of his maamorim, Pachad Yitzchok. Like their author, these works defy categorization and stereotype. They are hashkafah shiurim, mussar elucidations, soaring poetry, theological treatises, metaphysical novellae and so much more. It is beyond the scope of both this article and writer to reduce their transcendental significance into a few sentences and paragraphs. However, it may be useful to review just a sampling of the topics illuminated by the Rosh Yeshivah’s luminescence:

The entire history of Yishmael’s demands for Eretz Yisrael is made clear in a blinding moment of clarity (see Sefer HaZikaron, page 55); Hashem the Great Artist and the secret of miniatures (PY, Shabbos, page 101); the true nature of “Jewish sins” (PY, Purim, kuntres reshimos, No. 18); the recurring power of Maamad Har Sinai (PY, Igros, page 164); how Hashem both recreates the world and rests on Shabbos (PY, Shabbos, first maamar); and the intricate relationship between parents, teachers, yeshivos, and mesoras haTorah (PY, Shavuos, last maamar). These topics barely scratch the surface of the universal subjects treated in Pachad Yitzchok.

It should be noted that every written maamar or essay in the Pachad Yitzchok was first presented on a Shabbos or Yom Tov before hundreds and even thousands. Often, the maamorim were presented at a chassidic style tisch, preceded by haunting elevating nigunim. The intellectual content of the maamar was inseparable from the emotional, soul-captivating, heart-rending component of the experience.

The Rosh Yeshivah once explained that he limited these hashkafah presentations to the Yom Tov venue because only then did we all have the keilim — the spiritual vessels — capable of absorbing these flaming words. For this reason, the early published editions of the Pachad Yitzchok, before that name was even whispered, included a disclaimer on every page that these notes were openly designated for those who were present at the maamar. Although that stipulation was later dropped, when the maamarim appeared in hard cover with the name Pachad Yitzchok appended, the point had been made. These were no mere linear words on a page. They were meant to convey an existential dimension, not just a disembodied cerebral thought. The reader was challenged to resurrect the event, reexperience the emotions, and only then apply the mind to the ideas at hand. That is a Pachad Yitzchok maamar.

The other pillar of his life’s work — Yeshivah Rabbi Chaim Berlin — also bears the imprint of Rav Hutner’s singular perspective on molding bnei Torah. In 1938, the Rosh Yeshivah added the Mesivta Beis Medrash to the already existing elementary school. Later he would add a kollel. From the beginning, the Mesivta bore his personal insignia. This was a place where kavod haTorah — the glory and grandeur of Torah — would be manifest and inhaled with the very air itself. His stated goal was not merely to produce Torah scholars but gehoibene talmidei chachamim — “Torah Scholars of spiritual elevation” (Sefer HaZikaron, page 107). The Rosh Yeshivah’s self-appointed task was no less than to elevate the character of bnei Torah in America. Through his maamorim, body language, personal demeanor, the sublime use of music and song, he sought to create an atmosphere of palpable holiness and sanctity.

In Chaim Berlin, the relationship between rebbi and talmid was not predicated upon intellectual stimulation or even pedagogic success. The Rosh Yeshivah revealed that the essence of the rebbi –talmid relationship is taanug — the sublime pleasure and ineffable joy which the student receives from being in the rebbi’s presence, absorbing his essence and sharing in his very lifeblood. One of the Rosh Yeshivah’s scriptural proofs for this approach was the final meeting between the prophets Elisha and Eliyahu. Eliyahu asks Elisha to define what he has gained from his rebbi, Eliyahu. Elisha does not answer because words cannot express this kinship. It is beyond verbal abilities and would be diminished by mere description. It must remain in the consecrated realm of ecstatic silence (see Sefer HaZikaron, page 110).

Because He Was Here

Still, it would be inaccurate to identify the essence of the Rosh Yeshivah’s contribution to Klal Yisrael in either of these great gifts, immense though they were. The Rosh Yeshivah used to tell a story about the Gra that could well be applied to himself as well.

A man visited Vilna in the early years of the eighteenth century and was astonished to find that even a baal agalah — a seemingly simple wagon driver — could “talk in learning” like the greatest of scholars.

“How is it that you are so learned?” the visitor inquired of the man in peasant garb.

“Don’t you know; haven’t you heard? The Gra lived here,” the driver answered.

The visitor was unclear about the reference. “Was he the rav of Vilna?”

“No.”

“Was he the local judge?”

“No.”

“Well, then, was he the maggid — the preacher?”

“No.”

“Then what was he?” the exasperated tourist demanded.

“Veil er iz da gevehn — Because he was here,” the baal agalah triumphantly concluded (Sefer HaZikaron, page 37).

I believe that we can similarly say the same of the Rosh Yeshivah. Although his primary twin legacies are his yeshivah and written works, it was actually his very presence among us that ultimately left the greatest impact. We may attempt to explore aspects of his wisdom, greatness and teachings. But ultimately it was the totality of who he was that left an indelible imprint upon his generation and those born after his passing.

Indeed the Rosh Yeshivah’s passing itself, not surprisingly, provides a fitting coda to the symphony of his life. In Cheshvan 5741 (1981), he suffered a partial stroke in Eretz Yisrael but did not experience any speech deficit. Nevertheless, he said nothing about his condition other than occasionally mentioning to visitors that his mother’s name was Chana. When he did ask people to daven for him it was with the absolute proviso that all tefillos be said b’soch shaar cholei Yisrael — “among all the other sick in Klal Yisrael.” He made it clear that without this context, he did not want the prayers in his behalf.

Even when his condition deteriorated, he retained his sense of humor. One of his attendants adjusted his pillow and asked (in Hebrew), “Ha’im noach l’harav?” which literally means, “Is the rabbi comfortable?” However, the Rosh Yeshivah commented to his confidants, “They ask me about Noach, but I am already at Lech Lecha.”

What at first appeared to be a mere pun, became retroactively understood as a realistic description of the tragic situation. The Rosh Yeshivah also asked that the holy piyut “Bnei Heichalah” be sung to him several times during those days, as it became ever more clear that he was preparing for the end. Several times during this period the Rosh Yeshivah requested his Shabbos clothing, declaring that he was hoping to arrive in “Yerushalayim for Shabbos.” Only later did it become clear that he meant the heavenly Yerushalayim (Sefer HaZikaron, page 259).

Our response to his life must be to continue to study his works, walk in his ways, and try to be the broad, deep, lofty, ever-growing, spiritually dynamic Jews he wanted and challenged us to be.

The Master Mechanech

The Rosh Yeshivah’s wisdom in chinuch issues was extremely practical, even though the ideas often flowed from the most esoteric of sources. He once dealt with the problem of laziness that seemed to affect a chavrusashaft of two otherwise bright and accomplished students. He called the boys in to his office and asked them to produce a booklet of chiddushim on a wide-ranging topic. They chose the subject of muktzeh and eventually produced a solid work of original Torah. The Rosh Yeshivah’s wry comment was that laziness can be cured by writing, because one cannot write properly in bed.

Rav Shlomo Wolbe, ztz”l, who met the Rosh Yeshivah when he himself was already a world-famous mashgiach and renowned baal mussar, nevertheless considered himself a talmid of the Rosh Yeshivah. He once related a profound line he had heard from the Rosh Yeshivah which sheds light upon Rav Hutner’s entire weltanschauung:

“The philosophers of the world labor with difficulty to find a place for G-d in the world because they are so mired in this world that it is difficult for them to discover G-d in their universe. Our sages, however, are so permeated with the presence of G-d that they find it difficult to find a place for the universe itself, since Hashem is so omnipresent” (see Maharal in his Siddur on Aleinu).

Over the decades, the thousands of his talmidim who entered chinuch at various levels consulted with him about every detail of pedagogy. Following are just some of the insights we all gained from him:

- A rebbi encountered a student who was an incorrigible liar. The Rosh Yeshivah counseled that he not be punished or reprehended. “Let him know that you don’t believe a word he says,” the Rosh Yeshivah advised. “If he says ‘good morning,’ tell him you don’t believe that it’s morning.” The student eventually picked up on the hints and became a reliable and truthful child.

- The Rosh Yeshivah was adamant that no punishment be related to a davar shebikedusha. For instance, he did not allow punishments such as reciting Tehillim, writing divrei Torah or extra learning. Torah must remain a positive experience untainted by any negative connotations.

- The Rosh Yeshivah was extremely realistic about the gap between ideal and actual chinuch He taught all his talmidim who ran mosdos haTorah, “The Alter used to say that a yeshivah ought to have three hundred mashgichim for every bochur. Instead we sadly have one mashgiach for every three hundred bochurim.” If we realize that the situation is basically untenable, we can get by. But if we live under the illusion that things are as they should be, tragedy will ensue.

- The Rosh Yeshivah opposed the educational shitah that advocated presenting Eisav, Yishmael, Bilaam, etc., to children as gedolim who possessed a subtle flaw. His strong contention was that children need to identify heroes and villains, virtue and evil. Later, much later, they can be taught subtleties and nuances. He utilized this opinion in the introduction of Gemara teaching as well. Some rebbeim, for instance, teach the basic definition of robbery by utilizing the innovative thought of Reb Chaim Brisker, that every ganav (robber) is a mazik. The Rosh Yeshivah strongly disagreed. “A ganav is a ganav and a mazik is a mazik,” he would say. “Later they can learn the Reb Chaim.”

The Rosh Yeshivah seems to have received his mandate to create talmidim who would in turn teach Torah to others from the choice of words used by the Gemara. In describing the exchanges between Rebbi (Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi) and Rav, the Gemara (Chullin 137b) depicts “bolts of light that went from Rebbi’s mouth to Rav’s mouth and back again.”

The Rosh Yeshivah was troubled by the “mouth to mouth” portrayal, which more naturally should have been called mouth to ear. His conclusion — which surely became a lifetime endeavor — was that the obligation to teach Torah includes the mandate to raise rebbeim, not just talmidim. And so, from the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah to the world of kiruv, to poskim, to roshei yeshivah and roshei kollel, Rav Hutner, ztz”l, helped assure the eternity of Klal Yisrael by producing rebbeim, not just talmidim.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 335)

Oops! We could not locate your form.