A Lasting Lesson in Humility

Only a 15-year-old who doesn’t know his place would continue the conversation at that point. And so, I continued

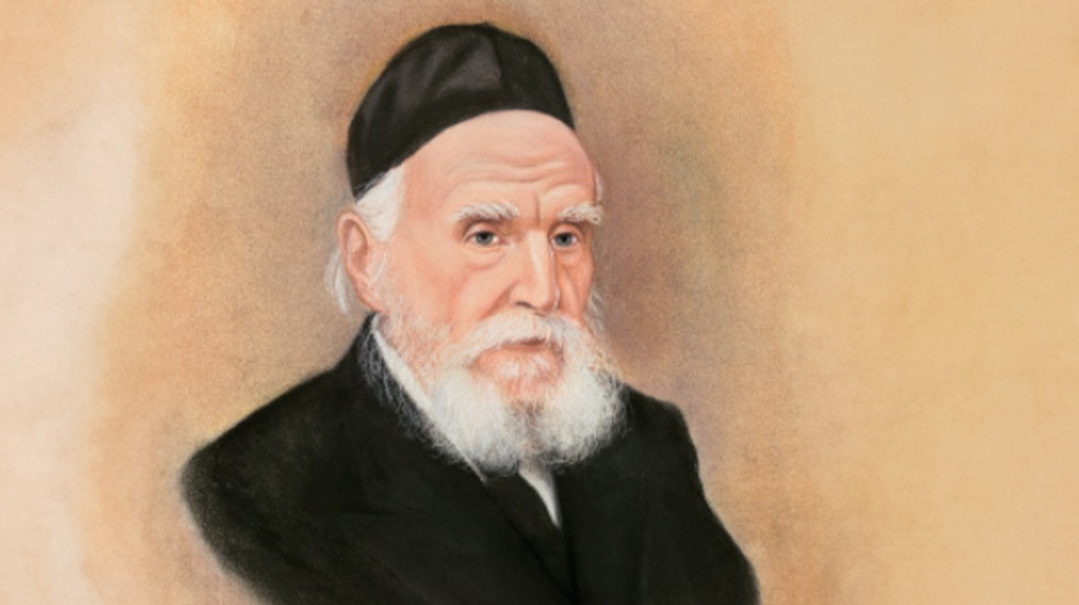

Though Rav Moshe Feinstein ztz”l left this temporal world decades ago, his legacy as gadol hador and towering posek still endures, as do of course the myriad stories of his gentle nature and middos tovos.

A personal interaction from my youth with this gadol taught me that the depth of his humility was of the same magnitude.

In the early 1970s, when I was about 15 years old and in tenth grade, the plight of Soviet Jewry was in the forefront of everyone’s mind. A major rally had been organized to take place on a Sunday in front of the UN, and tens of thousands of Yidden were expected to attend. I very much wanted to participate and lend my young voice to the chorus of “Let my people go.”

In those days, the yeshivah high school that I attended in Forest Hills, Mesivta Chofetz Chaim, was in session until 3 p.m. every Sunday. When a friend and I approached the menahel at the time, Rav Gavriel Ginsberg ztz”l (no relation) and asked him if we could leave early to attend the rally, he insisted that we wait until yeshivah was over at 3 p.m. and then go. We explained that the rally would long be over by the time we got there.

Though my friend gave up, I was persistent. I said that there must come a time when caring about Acheinu bnei Yisrael takes precedence over an hour of learning. Of course we assured him that we would make up for the missed hour on our own time.

Being the unique person and mechanech that he was, Rav Ginsberg didn’t just dismiss our request as teenagers scheming to get out early, but instead treated it as a serious hashkafic question of chesed versus Torah learning.

He said, “I am too small to take responsibility for two boys missing an hour of learning for this, so I will ask the gadol hador, Rav Moshe Feinstein, to issue a psak on this question.”

I thought he was certainly joking with us, but he grabbed my hand and led me into his office. He went to this desk and dialed Rav Moshe directly. Rav Moshe soon came to the phone and listened to the question, and then responded that we should not leave yeshivah early for the rally. Rav Gavriel thanked Rav Moshe, and the discussion was over.

Or so I thought.

AT 3 p.m., when shiur was over and I walked out of the classroom, I saw that Rav Gavriel was waiting for me. He asked me to come into his office because he wanted to talk to me.

After we sat down, he asked me if I understood why Rav Moshe had paskened the way that he did. I told him that I did not understand, but I accepted his psak, and for me, it was over. I will never forget his response to me.

He said, “If you don’t understand why Rav Moshe said that, then it’s not over. Until you understand it, you will not have learned any lesson from this incident for the future.”

A bit confused, I asked him, “So what do you suggest that I do?”

And he responded, “I know Rav Moshe is home this afternoon, so I want you to go to him and ask him to explain it to you.”

I, a 15-year-old boy with a poor command of Yiddish, should go to the gadol hador and question his earlier psak? I looked at Rav Gavriel to see if maybe he was joking. Maybe this was some kind of lead-up to color war? But he was totally serious and was very insistent that I go.

Prior to that, I had only met Rav Moshe two or three times. A few years earlier, when Rav Moshe came to an annual parlor meeting at the home of one of his earliest talmidim, Rabbi Saul Lasher, my father brought me along to get a brachah from the gadol hador. Other than that, I had never spoken to him. I had also hardly ever been on a train before, and I had no idea how to even get to the Lower East Side.

However, Rav Gavriel was resolute, and before I knew what had happened, I was sitting nervously on a train heading to the Lower East Side apartment of the gadol hador.

I was welcomed in warmly by the Rebbetzin and escorted into the small dining room, where Rav Moshe was sitting with a Gemara open in front of him. He looked up at me with the most angelic smile I had ever seen.

I began by apologizing for bothering him. Then I worked up the courage to ask him why he felt that it was not very important to go out and support the mass effort for Soviet Jewry. Softly and gently, he explained that bnei Torah have a different responsibility and don’t protest or demonstrate like the rest of the world does. It is not our way.

Only a 15-year-old who doesn’t know his place would continue the conversation at that point. And so, I continued.

I asked the gadol hador that if bnei Torah are not allowed to protest or demonstrate the way the rest of the world does, then why shouldn’t they have their own gatherings to go to, in the manner befitting to them? After all, isn’t a message being sent to the young yeshivah boys today that the predicament of our brothers and sisters in the Soviet Union is not our concern?

As soon as the words came out, I realized the absolute absurdity of this scene. A young 15-year-old yeshivah student (and a struggling one at that) was here giving mussar to the acknowledged posek hador for all of Klal Yisrael. I wondered if there were any rocks in the Lower East Side big enough to crawl under.

Rav Moshe was quiet for a few moments. Then he picked up the phone on his desk and dialed a number very slowly and deliberately. He began to speak to Rabbi Moshe Sherer and told him that he had a “yungerer bochur” with him who had asked a good question.

“I think the Torah tzibbur should organize a united tefillah gathering for the bnei Torah on behalf of Soviet Jewry,” he said.

They discussed it for a few minutes, and then Rav Moshe completed the conversation. Rav Moshe then took out a piece of paper, wrote down an address on it, and handed it to me.

He said, “This is the address of Rabbi Sherer’s office, and he is there now, it is close by. He is waiting for you to come, please go and discuss this with him.”

He shook my hand warmly and wished me much hatzlachah.

I had no idea how to get to Lower Manhattan, where the office of Agudath Israel was located, so one of the kind avreichim at MTJ drove me there in his car.

That was quite a day for a tenth-grade yeshivah bochur. I went from being treated so warmly by Rav Moshe, to meeting Rabbi Moshe Sherer, who spent considerable time talking with me about Agudath Israel and about the gadlus of Rav Moshe. And all of this for a 15-year-old who had never been on a train before.

Rabbi Sherer shared with me that Rav Moshe felt my point about sending the right message to the yeshivah bochurim of the day about Soviet Jewry was very important, and so he had asked Rabbi Sherer to organize, under the auspices of the Agudah, a large, united tefillah gathering for Soviet Jewry. He told me that he would start working on it the very next morning when his staff came in. He then walked me to the door and thanked me for my efforts in making this happen.

When I arrived home later that evening, I tried to absorb all that I had seen and learned that day. The greatest lesson of all was the incredible humility that Rav Moshe had displayed. Not only had he given his precious time to sit with a 15-year-old bochur, but he even listened thoughtfully and followed through on a question I had raised.

The Midrash tells us that when Amram separated from his wife Yocheved due to Pharaoh’s terrible decree — and all of Klal Yisrael followed suit — it was his young daughter Miriam (opinions differ as to how old she was then; some say she was six years old) who told him that he was acting incorrectly. He listened to her and went back to his wife, and the rest of Klal Yisrael followed suit. A case of the gadol hador listening to the voice of a six-year-old girl. And here we had the gadol hador paying attention to the voice of a 15-year-old kid from Forest Hills, Queens.

In the end, the tefillah gathering was an extremely important event and very memorable to all those who participated. For me, personally, as the memories of that event have slowly faded over the many years, the memory of the incredible humility of the gadol hador (and, of course, of Rabbi Sherer as well) will remain imprinted on my neshamah forever.

Rabbi Chaim Aryeh Z. Ginzberg is the rav of the Chofetz Chaim Torah Center of Cedarhurst and the founding rav of Ohr Moshe Institute in Hillcrest, Queens. He is a published author of several sifrei halachah, and a frequent contributor to many magazines and newspapers, where he writes the Torah hashkafah on timely issues of the day. He is also a sought-after lecturer on Torah hashkafah at a variety of venues around the country.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1014)

Oops! We could not locate your form.