A Heart Too Wide for Hiding Places

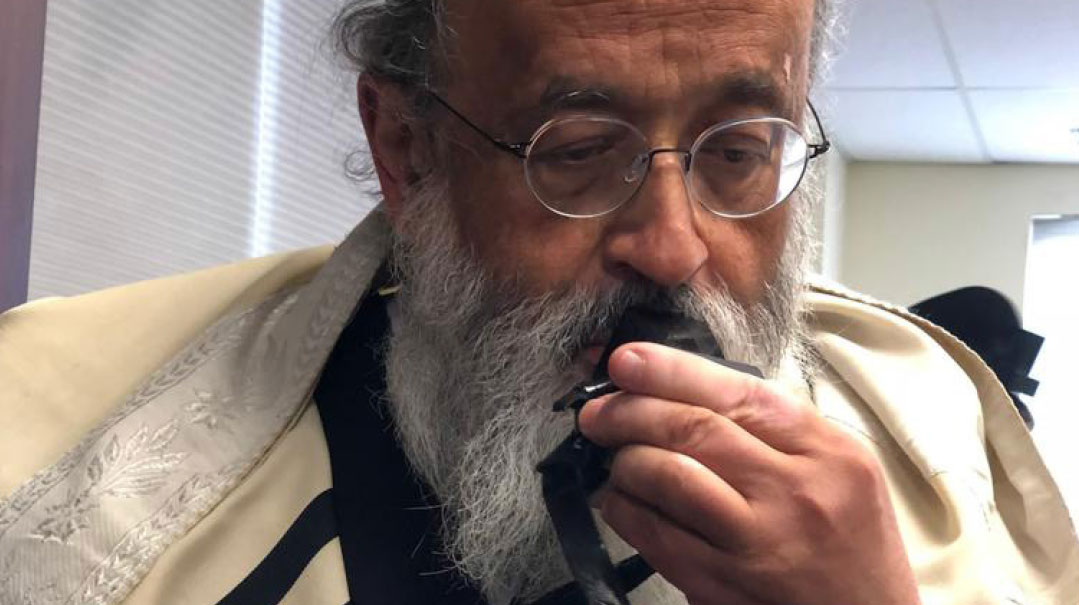

| July 29, 2020Learn it, love it, live it: In tribute to Rav Shmuel Tzvi Berkovicz ztz”l

Iwas eight years old. And I had been misbehaving again.

Rabbi Shmuel Berkovicz, the rebbi we feared most, and loved most, drove the school van on Sundays for the kids in my neighborhood. There was always some sort of contest — questions or Jewish history trivia — and somehow every kid always earned a prize. That Sunday, it was red Tangy Taffy, in a box between the front seats.

But that day, it was out of reach for me. I had messed up, after multiple warnings, and my father had asked Rabbi Berkovicz to withhold my treat. And so I sat huddled in the back, awaiting my deserved humiliation.

As we pulled onto Warrensville, the distribution began. Rabbi Berkovicz did everything with a flourish — each child’s name was called as the candy was passed back. I sank deeper into the cold upholstery.

“Shloimy Hoffman,” he boomed.

I sat bolt upright. The candy slipped into my pocket, almost like it fit.

The van stopped, I stepped out, and Rebbi was waiting. He put his hand on my shoulder and told me something that, 30 years later, still holds power:

“Shloimy, I wanted to give you that candy. But your father asked me not to, and a father knows best. But I couldn’t embarrass you in front of your friends. I passed you that taffy, and now I’m asking you to pass it back to me.”

The wonder of that moment. Rebbi understood, he cared — and he knew what to do.

*****

It was the story of his life — a story that leaves us wishing for more chapters. When he was shockingly, suddenly niftar last Wednesday at the age of 63 after a very short illness, the Passaic shul of which he was rav, Khal Yereim, sent out the message, “Baruch Dayan Ha’Emes. It can’t be true.”

A Toronto native with a chassidish background (he kept the havarah his whole life, to honor his father), Reb Shmilu learned in Telshe under Rav Mordechai Gifter. After marrying Rochel Brandwein, he stayed in Cleveland after kollel and beginning a long, fruitful career in chinuch. He taught fourth grade for many years at Mosdos Ohr HaTorah, eventually becoming the menahel. After serving in that position for over a decade, he and his rebbetzin moved to Passaic — since so many of their children lived in Lakewood then, there was a natural pull.

Rabbi Berkovicz joined Yeshiva Ktana of Passaic as menahel of the third, fourth, and fifth grades. And there he again began applying his particular talent, as he did for me with the Tangy Taffy.

There was a boy who left Yeshiva Ktana. He needed something different. Rabbi Berkovicz learned with him for six months to ease the transition.

A year and a half later he called the boy’s parents. “What’s with high school?”

They had identified a possible option but didn’t know enough about the place. He offered to accompany the bochur’s father the following week on a reconnaissance mission. When the father was called out of town on business, Rabbi Berkovicz kept the appointment himself, sacrificing a night seder to scope the place out. He called the parents afterward to discuss the pros and cons.

Another struggling boy, a similar story. There was a meeting at school, and Reb Shmilu, who had only just moved to Passaic, listened in. Someone mentioned an option in Monsey. The next morning these parents got a call.

“My name is Shmuel, your new neighbor from down the block. I’m on my way back from that school in Monsey and have some insight in how they may help your son. Can we meet?”

He was a gifted, passionate rebbi, full of creativity. His spectacular worksheets, produced by hand, featured splashes from his four-colored pen and his beautiful rounded handwriting.

My friends and I reminisced at the levayah, or on the phone, chanting a familiar refrain: “Shechitah. Kabbalah. Holachah. Zerikah.” We remembered what he taught, because we remembered how he taught — with his whole heart and his full neshamah. He invested every ounce of the talent he was blessed with in the job he never stopped loving, never stopped revering.

He demanded that his talmidim excel to the fullness of their potential. His classroom was by no means a “Rebbi loves you and understands your challenges, do anything you want” kind of place. But we felt secure knowing he was a “Rebbi loves you and understands your challenges, you can achieve anything you want!” kind of man.

Rebbi knew each talmid’s name years after graduation — partly because he genuinely loved them, but perhaps also because of the rapport he built with the parents. He invested in them, made them understand they were his partners. When a bar mitzvah boy leined in the school minyan, Rebbi laid his phone near the bimah because the mother deserved to hear.

A torrent of handwritten notes, calls, and texts. “Your child did something special. We got nachas today!” Always “we.” Your child is like mine, my talmid is yours, and we are building someone special together.

*****

As he rose through the ranks of his profession, he never forgot why he had chosen it all those years ago, as a yungerman who had internalized the achrayus of Telshe. He was teaching the Bashefer’s Torah, to Yiddishe kinderlach. For him it was a privilege and a holy responsibility.

Rabbi Shmilu Berkovicz was good at chinuch because he was good at people, and he understood that kids were people too. That gift was apparent from a very young age, even as a bochur in Telshe.

A friend remembered the meat packages from Perl’s in Toronto. Back when there weren’t stores on every corner, if you were lucky enough to get a package from home, it was carefully hidden, to be savored alone late at night. When a package came for Shmilu, he stood in the dining room and declared open season. His heart was too wide for hiding places.

He formed a group among the bochurim. It was dubbed “the chaburah.” There was no charge for admission. Everyone was welcome. Background or learning ability didn’t matter. The desire to be a ben Torah — to drink the waters of Telshe and follow the derech of the rebbeim he revered — was all that qualified you for membership. There are bnei Torah scattered throughout the world who owe their way of life, and the generations that followed, to the pride he instilled in striving to become a ben aliyah.

“Learn Torah. Love Torah. Live Torah.” The refrain he sang to his talmidim all his life, he was singing back then. Never just to himself but to every Jew he could find.

It didn’t matter what school your kids were enrolled in, which shul you davened in or what kind of yarmulke you wore. He captured everyone’s heart. And he brought them close to his own. It made him the natural choice to serve as rav of the new nusach Sefard minyan on Passaic’s Main Avenue, so soon after his own arrival. He suggested it be named Khal Yereim after the shul in Cleveland he loved so much.

During the terrifying months of coronavirus, his Shabbos afternoon seudah didn’t start until well after two. He traversed the neighborhood with his wife, knocking on doors, standing on porches, and giving chizuk. The boy who brought a knish from home to warm up every day got a special regards. “I’m looking for my knish boy! I miss our special time.”

A rebbi in school was honored at a yeshivah dinner in Monsey. There was a couple who had a bochur in the yeshivah, as well as a child in that rebbi’s class. A video presented at the dinner included footage of their younger son learning together with the honoree. They later found out that the clip had only been inserted at the behest of Rabbi Berkovicz, who knew those parents would be in attendance. He sent it to the yeshivah office and asked that it be added so they could enjoy the nachas.

My grandmother was his neighbor in Cleveland. She loved his family and she loved how Rabbi Berkovicz told everyone, as loudly as he could, of his privilege at having the best shochen tov. It was the only place she would eat Shabbos when my parents were away.

*****

The burden he carried was heavy, but not for a moment did his family get lost in the shuffle. The shalom bayis in his home was gold standard and his rebbetzin Rochel tibadel l’chayim was his full partner in all that he accomplished. And he made sure everyone knew it.

He knew exactly what each of his children needed, where each einekel was holding. The grandchildren had daily Zoom calls with him in recent months. He sent his children questions, tailored for each grandchild to shine, the night before the call to make sure they were prepared with the answers, to earn Zeidy’s prize.

There was a childless man in Cleveland. When he moved into an assisted-living facility, Rabbi Berkovicz was there every Friday with his kids to say good Shabbos. It’s one example among many. He passed on his sense of achrayus to them.

I remember he had a Mishnayos chavrusa Shabbos morning before davening. They became the dearest of friends. Long after he had left town and moved to Passaic, if he had occasion to spend Shabbos in Cleveland, he would walk up to his erstwhile chavrusa and ask if they were on for the next morning. As if he had never left. His friend showed him the Mishnayos still in his shtender.

It was understood. No matter where he moved on, he never left anyone behind. To us, he was Cleveland. We couldn’t imagine Rabbi Berkovicz being associated with some other town. And yet after he was in Passaic for just ten years, people there now feel the same way.

I called a member of his Passaic kehillah, a doctor who was in his office, between patients. When I mentioned Rabbi Berkovicz, he could no longer speak. He just cried, and with those tears he conveyed what no story could.

Later, he called back. “When he walked into shul, it felt like Dad was in the room.”

He remembered Rabbi Berkovicz’s first weeks in the shul, his derashah touching a place deep inside. When he noticed that the Rav knew his children’s names even before he himself had had a chance to be introduced, he knew he had found his home. “My life forever changed that day, along with my family’s. He taught us what we are supposed to be doing on this earth, and he did it with the biggest heart I have ever been privileged to know.”

A child of a mispallel was undergoing a medical test the day of Reb Shmilu’s son’s chasunah. Late in the afternoon, he called the mispallel to hear the results. The man was incredulous. He would see him in just a few hours at the wedding.

“I need to know,” said Rabbi Berkovicz. “It’s sitting on my head.”

Homework every night with orphans or children from troubled homes. Streams of phone calls to widows every Erev Shabbos. Special-needs boys for whom he made a place at school, and the parents who survived on his love.

Throngs of people leaned on him, yet they were never made to feel they were names on an endless list. Each one was the only one, everything was done quietly. He needed nothing except the success of the person he was trying to help.

He carried hearts like diamonds in his loving arms, and never let go. And he was always looking to take up some more.

Those hearts are broken now.

Elevated, because we were touched by the giant heart of Rav Shmuel Tzvi Berkovicz, zeicher tzaddik livrachah.

Yet broken.

The man who captured our hearts has fallen. Who will carry our hearts on?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 821)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (1)