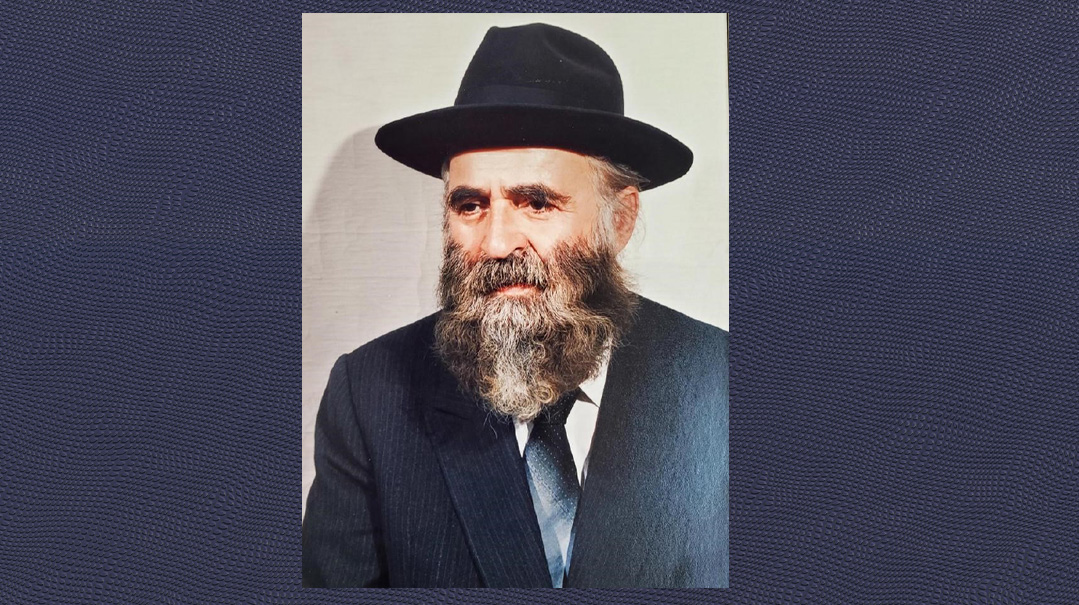

A Giant’s Shadow

| January 10, 2023The twin legacies of Torah and chesed of Antwerp’s Rav Chaim Kreiswirth ztz"l will always endure

Photos: M.B. Goldstein (from the archives of I. Morsel and P. Kornfeld)

Twenty-two years have passed since Rav Chaim Kreiswirth ascended to the Yeshivah shel Maalah on 16 Teves 5761, and although his name still echoes through the Torah world, in another sense the Rav’s memory is fading. After his Torah manuscripts were lost on a plane journey, Rav Kreiswirth never wrote another, and there is no published biography to capture his unique personality and achievements for another generation. Likewise, many of those closest to him have already passed on to the Next World as well.

Yet to the individuals he impacted and the wider community he transformed, Rav Kreiswirth was an unforgettable influence. He’s described as a “cheftza fun chesed — an object of kindness,” who knew no limits in caring for individuals and the downtrodden. His brilliance in learning was paired with a focus on bringing Torah to the front and center of communal consciousness, and his oratory brought mussar to life.

On a trip to Antwerp, where Rav Kreiswirth was rav for almost 50 years, we met with his close disciple Rav Boruch Wasyng, rav of the Beis Yaccov shul and maggid shiur emeritus in Eitz Chaim yeshivah of Wilrijk; and with Mr. Issy Morsel, diamantaire, askan, and chairman of the kehillah’s Yesodei HaTorah school, who was drawn close to Rav Kreiswirth and cowrote a sefer about his towering personality.

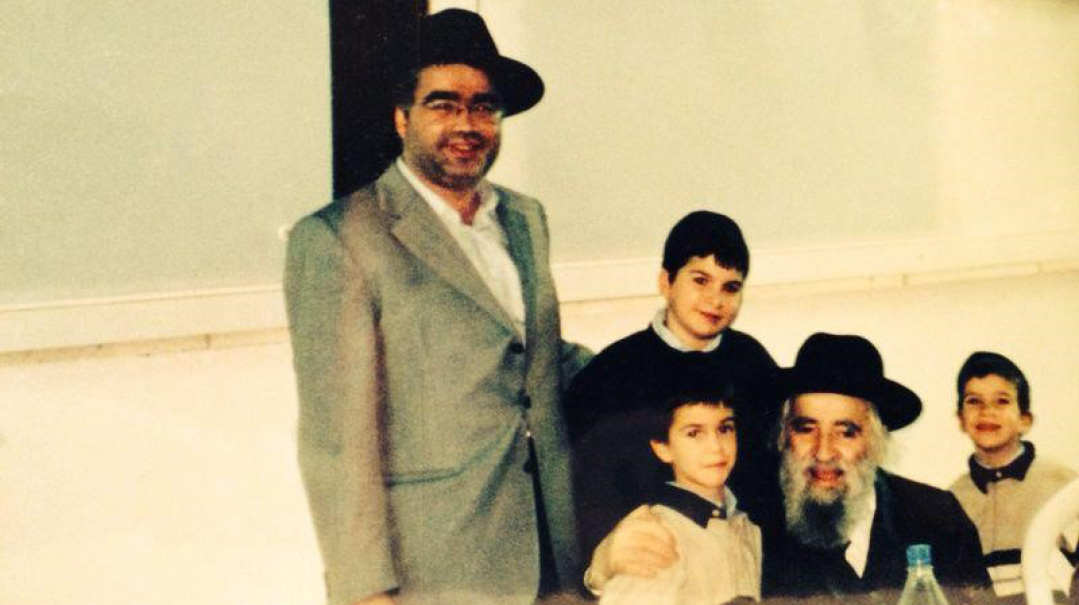

Rav Kreiswirth leading his son, Rav Dov Tzvi, to the chuppah together with his mechutan, the Pittsburgher Rebbe, Rav Avrohom Abba Leifer. (Rav Dov Tzvi, rosh yeshivah of Toras Chaim in Jerusalem in memory of his father, passed away in 2021)

An Enduring Influence

Today, Rav Boruch Wasyng is one of Antwerp’s most respected talmidei chachamim. But in 1954, as a young child standing among the row of schoolboys who flanked the path along which the new rav of the town would walk into Antwerp’s historic shul for his inauguration, he never expected Torah study to be his future vocation. He didn’t realize then that Rav Kreiswirth’s influence would determine his future.

“When I saw the Ruv for the first time, his presence was like the stanzas of ‘Mar’eh Kohein’ coming to life. His personality shone forth. He had a full black beard and impressive hadras panim, and the derashah he gave absolutely astounded the crowd,” he remembers.

Over the next few years, the Rav, who served also as nasi of Yesodei HaTorah, came to farher Wasyng and his schoolmates regularly. “My parents wanted me to attend the ‘Yishuv’ yeshivah high school in Eretz Yisrael, which had secular studies alongside the kodesh, and offered matriculation exams. I was accepted, but Rav Kreiswirth, together with Rav Yonason David, pushed me to go to Yeshivas Beer Yaakov instead,” explains Rav Wasyng. (Rav Yonason David spent a year in Belgium shortly before he became the son-in-law of Rav Yitzchok Hutner. During that time he taught the highest class in Yesodei HaTorah.)

Rav Shlome Wolbe, the mashgiach in Beer Yaakov, was Rav Kreiswirth’s brother-in-law. After five years in Beer Yaakov, Rav Wasyng continued to Yeshivas Ponevezh.

He was far from the only one who changed direction; the new rav transformed attitudes towards limud haTorah throughout his community. Rav Wasyng explains the zeitgeist of Antwerp back in those early postwar years. “The people here were war survivors, Poilishe balabatim. Many didn’t see the point of sending boys to yeshivah. It was totally normal for a boy to go to work from age 15. But the Ruv simply didn’t stop talking about Torah, Torah, Torah and people who never would have gone to yeshivah went there, because of him.”

Behind his desk in his large office in the diamond bourse, Mr. Issy Morsel speaks with great animation and not little emotion as he shares his memories and perspectives of the gadol he was fortunate to know and assist. The uniquely Antwerpian pronunciation of Rav Kreiswirth’s local title, “the Roov,” in a Galician-French synthesis, carries a world of longing and reverence.

“Torah wasn’t on people’s minds,” Morsel puts it simply. “They needed to establish families, find a way of making a living, find accommodations for their families. Torah wasn’t front and center. The Ruv was giving a shiur to balabatim, many of whom didn’t know who the Steipler and the Chazon Ish were.” Rav Kreiswirth’s constant talk about Torah and kevod haTorah raised the banner of learning high.

There was a story he liked to tell about the Netziv of Volozhin. The Netziv once called his grandson, Rav Chaim Brisker, in the middle of the night. Rav Chaim brought his rebbetzin along, sure that it was an emergency, and when he arrived at the Netziv's house, the Netziv explained why he had called him. “Z’is mir eingefallen a teirutz of di Tosafos! — I just thought of an answer to the Tosafos!”

Rav Chaim said he wasn’t yet quite ready to hear it, because he hadn’t said Bircas HaTorah, and his grandfather started to cry. “It’s four in the morning, and you haven’t said Bircas HaTorah?!”

Rav Kreiswirth told this story with an emphasis on the yeridas hadoros. “Pas shel Shacharis everybody knows about today, but Torah shel Shacharis — that’s not well-known at all,” he’d lament, pushing his audience to take learning more seriously.

Rav Kreiswirth would reminisce with excitement about how he had jumped onto a train in Vilna in order to speak in learning with the Rogatchover Gaon, who was passing through while traveling to Vienna to see a doctor. He stood up like a lion for the honor of Torah, not hesitating to rebuke those who took it lightly, both in his correspondence and in his public speeches.

But more than even the most powerful derashah was the impact of his personal example. Rav Wasyng was a young boy when he once went to Rav Kreiswirth’s simple apartment to speak to him, and was told to wait because the Rav was learning. More than 60 years later, with wonder and longing in his voice, he recalls, “I could not understand the meaning of the words at that time, but the sound of his learning, the beauty of his voice learning aloud a Rashba on Gittin, made me wish I could just wait there and listen to him for an hour.”

After Rav Kreiswirth lost his Torah manuscripts on a plane journey, he never compiled his chiddushim into a manuscript again. Although there exists a collection of the derashos he gave, Rav Wasyng says that it is simply impossible to capture their potency on paper.

“I’ve seen many baalei kishron and many photographic memories over the years, but when Rav Kreiswirth spoke, it was like the Gemara spoke through him. It was ‘Shas medaber mitoch gerono.’ You can read here on a page ‘Omar Rabi Yochanan,’ but it doesn’t compare at all to the impression made by Rav Kreiswirth saying ‘Omar Rabi Yochanon.’ ”

Aside from his encyclopedic knowledge, he was a gifted orator. Rav Kreiswirth told Rav Baruch Wasyng that in Poland there were many towering talmidei chachamim too, but when he came from there to Lithuania, he picked up the skill of explaining and expounding on Torah that existed there alongside the depth of learning. He used to give a Chumash shiur on Friday nights, which was so fascinating that non-Shabbos observant Jews from the more assimilated community of Brussels used to drive in for it.

“I once said to the Ruv that those two attendees who were mechallelei Shabbos were the proof of how good his shiur was,” Issy Morsel says. “Local Yidden might have been coming to the shiur because of frumkeit, because they felt that on Friday night they should be doing some learning. But the people from Brussels were drawn by the shiur itself. They could not be dissuaded from driving in to hear the Ruv’s oratory. The Ruv said to me, ‘That is why we had to cancel the shiur.’ ”

Whether in gatherings with holy rebbes or celebrating with his beloved community, for Rav Kreiswirth, it was always about spreading Torah and helping another Yid

Legendary Abilities

Described by the Dvar Avrohom of Kovno in a letter with the words “you never saw such a baki in Shas Bavli and Yerushalmi as this bochur who has come here from Poland,” Rav Kreiswirth’s attainments in learning and his quick recall were the stuff of legends. When someone started to speak about a sugya or a halachic topic, the Rav could easily take over the conversation, whatever the topic was. It was as if all was open in front of him. He was close to roshei yeshivah, talmidei chachamim, and gedolim across the spectrum of the Torah world, and used to bemoan the fact that he couldn’t devote endless hours to sit and learn, due to his responsibilities as a communal rav.

Originally from Wojniczin, Poland, Rav Kreiswirth came from a home plagued by poverty yet permeated by chesed. As a bochur, he gave up his bed for an old man and slept on the floor for a few months, a zechus which he felt saved him from the Holocaust. He would repeat the memory of his bar mitzvah, spent in yeshivah. “My father didn’t come. Ask me why. Because it was in a different town, and he had no money. He could have borrowed money, you’re thinking. But you don’t borrow money which you have no way of returning. Today people think that borrowing is a source of income.”

After the invasion of Poland, the young bochur ran to the safety of Vilna, where hundreds of yeshivah bochurim had gathered. As he crossed the Polish-Lithuanian border, a soldier caught sight of the fugitive and raised his rifle. Chaim Kreiswirth begged for his life. The soldier seemed to be relenting, but then said “I have to shoot, I can’t let you through.” “So you shoot into the air, and I will run into the forest,” Chaim suggested quickly. Remarkably, the soldier listened.

The brilliant bochur married Sara, the daughter of Rav Avraham Grodzinsky, menahel of the Slabodka yeshivah. Later, when the war was over, Rav Shlome Wolbe became his brother-in-law by marrying Rivka, his wife’s sister.

The scheme dreamed up by Nathan Gutwirth (Mrs. Wasyng’s father) which procured transit visas for hundreds of Mirrer bochurim got Chaim Kreiswirth out of Lithuania, but instead of continuing to Kobe, Japan, and then to Shanghai, he went to Moscow, then to Eretz Yisrael. From 1947 to 1953, he was rosh yeshivah of the Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, Illinois, where Rabbi Berel Wein was among the prominent talmidim, until he accepted an offer from the kehillah in Antwerp.

The following well-known story from his time in Skokie is an illustration of Rav Kreiswirth’s sharpness. A talmid of the yeshivah passed the bechinos and received a heter hora’ah. Afterward, the yeshivah felt compelled to rescind the heter hora’ah, due to the man’s misdemeanors, which were inappropriate for a rabbi. He took them to a secular court, claiming that he had rightfully earned his “diploma,” and the college could not rescind it in retrospect.

Rav Kreiswirth came to the court, holding his Gemara, and explained the yeshivah’s position to the judge with utmost clarity and simplicity. “A heter hora’ah is not a diploma,” he said. “It is a license. If someone gets a driver’s license and then breaks the rules of the road, the license is taken away.” The precise explanation convinced the judge, and the case was dismissed.

Last year, a clip circulated of Rav Ovadia Yosef ztz”l reminiscing with Rav Bentzion Kook about Rav Kreiswirth, who was Rav Kook’s uncle by marriage. “I know people who know Shas, but to know it word for word, that is only Rav Chaim. I heard him speak at the Laniado Hospital opening. He repeated entire sugyos, with Rashi, word for word. There is no one like him,” Rav Ovadia reiterates admiringly.

Rav Kook adds a story of his own. “The Rav was honored with Brachah Acharitah at a sheva brachos and he asked for a siddur. People wondered aloud why the Rav needed a siddur — after all, the words are from a gemara in Kesubos. “In order to know when to stop,” he clarified.

Culture of Chesed

Rav Chaim spoke a beautiful, rich Yiddish. The Jewish community in Antwerp is well-known for its multilingualism, but its distinctive Polish Yiddish is its most iconic tongue. In fact, even non-religious Belgian Jews still use that dialect among themselves and can be heard conversing in a zaftigeh [juicy] Yiddish.

“Rav Kreiswirth used to say that each language has its own inborn koach and is used for its own purposes. He disliked using French [although it was very much in use among that generation of the Jewish community in Belgium] and said that English was ‘the language to make money in,’ ” says Rav Wasyng.

Rav Kreiswirth’s concepts of chesed and tzedakah were in a league of their own, and he is credited with creating a culture of chesed in the Antwerp community. His hand was open to every good cause, and his yardstick seemed to have far bigger notches than most people’s. Local legend tells that during his tenure, a large family lost their father and breadwinner. During the shivah itself, the Rav collected a million dollars for the widow and orphans.

“The Ruv once came to a big philanthropist in the diamond district,” Rabbi Wasyng retells, “and began to persuade him to contribute to a cause. Of course, he had approached this man many times before, but he still made an impact as if it were the very first time, speaking about the mitzvah involved with such warmth and chizuk. The response was ‘My safe is open. I am going to the other room, and you help yourself.’ And the Ruv took what was needed.”

This wasn’t the only time the Rav’s fundraising methods achieved spectacular results. Issy Morsel shares more details. “Rav Kreiswirth was 82 at the time one family lost a breadwinner, but he took the [fundraising] burden on himself. Of course, he went to secular Jews too. The Ruv asked someone to accompany him to solicit funds from Mr. S., a very wealthy fellow. When they came to S.’s office, the elevator was broken. The other man, who was friendly with S., suggested that they return another time. The Ruv said ‘No, I want to go up now,’ and, with great difficulty, he made his way up to the seventh floor and explained his mission.

Mr. S. had a question for the Rav. “Do you give your charity funds to secular Jews too, or only religious ones?”

“I will give funds to anyone who learns Torah,” was the Rav’s quick comeback.

“I don’t see why I should give you. I give money to the poor in Israel and to the Keren Kayemet fund,” the man said. Then he turned to his friend. “The elevator is broken. How did the rabbi get up here?”

“He walked. He said he just has to come up.”

The donor couldn’t believe it, and respecting the Rav’s efforts, ended up giving a donation of $20,000.

When they came down the steps, the Rav said with satisfaction, “This is what I meant [to happen].”

He didn’t hesitate to use his sharp tongue to those who didn’t want to give. He once commented to someone who declined to donate money to a certain cause, “It’s a mazel that you are not a Kohein. And if you are a Kohein, you can’t duchan, because you have a mum.”

“A mum?! I don’t have a mum.”

“Yes, you do. Your hands are too short. They don’t reach your pockets.”

At one point, hundreds of Russian Jews who had left the former Soviet Union arrived in Brussels. Another group headed to Vienna, where they were cared for by Satmar-affiliated askanim. In Brussels, the Catholic Church’s welfare arm, Caritas, welcomed the refugees into their fold and provided relief. The Israeli Embassy in Brussels asked the local Jewish community not to care for these Jews, since they had turned down the opportunity to live in Israel. The official Zionist attitude was that if they didn’t want to live in the Zionist state, let the Catholics take care of them, let them rot in the Church.

Rav Kreiswirth was not cowed. He set out to provide these people with the money they needed and set them on their feet so they would not fall into the arms of the church.

“It was moirehdik how the Ruv collected for this cause,” Issy Morsel says. “He needed big money, so he went to the secular Yidden to convince them, too. He visited Bram Laub, one of the richest people in Antwerp, a totally secular Jew, and asked for his help. Laub explained that he had just gotten a phone call from the embassy telling him about this group and warning him not to get involved in helping them.”

“The Ruv said, ‘Come with me.’ ” Morsel gets emotional as he recalls the Ruv’s passion. “He took this man along to Brussels to meet the people and see the situation, how the church was wooing them with money. Once Mr. Laub saw it, he said ‘I don’t want to hear any more about Zionism. I only want to hear about Kreiswirth.’ Until the end of his days, he helped the Ruv collect for his causes.”

Rav Wasyng recalls the time the Rav was spotted in Brussels carrying bags of clothing for Russian Jews. “A balabos asked him what the Ruv was shlepping. When Rav Chaim answered, he said, ‘Why not take a taxi?’

“If I would have money for a taxi, I would have another bag of clothes,’ Rav Chaim said.”

During the week, the Rav could be found davening Shacharis mingling among the people in the Beis Yaccov shul. He had a room there where he would give tzedakah, while the crowd enjoyed a simple breakfast and a schmooze next to the beis medrash. Giving out money to meshulachim meant emptying his pockets on the spot.

Rav Wasyng, who is the rav of this shul today, says that some community members begged Rav Kreiswirth to stop and consider, perhaps overnight, before answering the collectors, but he never declined to donate immediately. He remembers an occasion when a collector approached the Rav with a letter of recommendation from a certain rosh yeshivah.

“The Ruv said ‘I’ll also give you a letter, but I’ll give you a letter with the signature of the Belgian finance minister.’ He then took a 5,000 Frank note, which carried the signature of the minister, and inscribed it in Lashon Hakodesh, ‘Let others learn from me and do likewise,’ with his own signature. That was his ‘letter of recommendation.’ ”

Rav Kreiswirth’s generosity wasn’t limited to his own townspeople; for the Rav, helping a Jew from London or Yerushalayim or America was all the same. He had no conception of borders in chesed. He would make phone calls to his balabatim on behalf of collectors from abroad and accompany visiting roshei yeshivah on their rounds.

“We tend to see our own family, our own neighborhood, our own kehillah, our own country as important, but the Ruv helped Yidden everywhere. Some people couldn’t see why Antwerpian Jewry should support yeshivos in England. They felt British Jews should take care of their own. But Rav Kreiswirth just opened his hand,” says Morsel. “He once told me that ‘just because governments laid down borders, making separate countries of France, Belgium, Germany, England, that’s not going to limit my gemilus chesed.’ In an increasingly fragmented world, it made no difference to Rav Kreiswirth what kind of Jew needed help. It was all one to him.”

On one trip to America just two years before he was niftar, Rav Kreiswirth made several calls to askanim to arrange treatment on behalf of a young man who was unwell. When his host asked how he knew this person, the Rav replied “He is my shuchen [neighbor].” The man was confused. “From where?” “I sat next to him on the train here in New York.”

One of the rabbanim to whom Rav Kreiswirth was extremely close was Rav Yehuda Aryeh Trager, a rosh yeshivah in Antwerp and the son-in-law of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. Issy Morsel tells us that Rav Kreiswirth was known to disagree with Rav Trager on one point. Chazal rule that the poor of one’s own city have precedence with tzedakah funding, but does this rule of priority also apply to supporting local Torah institutions over others? If a philanthropist in Antwerp could choose between financing a kollel in Antwerp or in Yerushalayim, or in Manchester or in New York, does he have to pick the local option? Rav Kreiswirth’s opinion was that talmud Torah is above borders, and can be supported anywhere, with no specific priority, whereas Rav Trager opined that locals come first “because if you don’t support the local talmidei chachamim, they will become impoverished.”

What about the poor of Antwerp itself?

“During the last ten years of the Ruv’s life, when the diamond industry here was in decline and the incredible prosperity of the postwar diamond boom had faded, the Ruv often mentioned in his derashos a tefillah that ‘the tzinoros [pipes] of shefa should open once again in Antwerp.’ It was on his mind.”

Lesson for Life

Rav Kreiswirth saw both the trees and the forest. He had his finger on the pulse of the town’s educational scene, directing the schools and yeshivos down to minutiae like appropriate dress for the rebbeim and their salaries. As a member of the board of governors of Yesodei HaTorah, Issy Morsel knew he was accountable to the Rav’s daas Torah.

“Once, we decided to terminate the employment of a couple of teachers from the school, because their best years had long passed. Usually the Ruv did not agree to fire people, but this time he did. He let us send away those two teachers. So we did, on a Friday. That Sunday, the Ruv called me to say he had changed his mind, and we had to take them back. ‘If you can send someone away from his job on Erev Shabbos, you don’t understand the gravity of what you are doing. And if you don’t understand the gravity of dismissing someone, you cannot be the one to do so.’ He quoted a gemara in Bava Metzia that says when you go to put someone in cheirem, you must wear black clothing. We had to ask mechilah from these rebbis and take them back to part-time jobs. The Ruv was so disappointed in me; I can never forget the lesson.”

Every rebbi and teacher mattered; and every child mattered, so, so much. The secular studies in Yesodei HaTorah have to meet strict government curriculum guidelines, but nevertheless, with Rav Kreiswirth as the ultimate decision maker, there was room for compassion. In order to graduate with a diploma, high school students have to pass the government tests at each year’s end. If someone fails, there is one chance in September for a retake. Otherwise, the student has to redo the year of studies.

Mr. Morsel recalls one case when this happened in the girls’ department. “Although he was himself a genius, the Ruv had such compassion and understanding for the girl who could not pass her exam. He felt for her, for how she had spent the summer studying, only to fail the September retake. He didn’t feel she should have to redo the year.

“Then the Ruv checked the lists and found that she had a younger sister in the next grade, making the idea of going down a class even more humiliating. He knew this girl would suffer terribly. So he said it would be impossible for her to resit the year. I conveyed this to the head of secular studies, but he wouldn’t listen to me. The Ruv went in to the director himself to say he couldn’t allow this to happen, and a solution needed to be found.

“The director insisted there was no solution. They would have to close down the school. So the Ruv replied immediately ‘We will close it down.’ It wasn’t a bluff. His sincerity was so obvious that the director backed down.”

Rav Kreiswirth was so close to Rav Boruch Wasyng that he sometimes came to join him for Melaveh Malkah, knocking on the door of the Wasyngs’ apartment unannounced. They would speak in learning and spend time together. If Rav Kreiswirth needed to accomplish something, he would pick up the phone and make calls right there.

(Right) Mr. Issy Morsel: “The Ruv was giving a shiur to balabatim, many of whom didn’t know who the Steipler and the Chazon Ish were”

(Left) Rav Boruch Wasyng: “Giving out money to meshulachim meant emptying his pockets on the spot”

Pushing Further

After Rav Kreiswirth suffered a severe illness and underwent surgery in Boston, the Steipler told him that the Mishnah in Eilu Devarim mentions hachnassas kallah between bikur cholim and levayas hameis, meaning that being involved in raising funds for poor brides is a buffer between sickness and death. The Rav took this to heart and increased the scope of his fundraising activities, traveling the world to raise tzedakah funds and give his powerful derashos. He lived for another 20 years.

During his final illness, his son, Rav Dov Tzvi Kreiswirth, spent much time at his bedside. When his condition deteriorated, and he was advised to enter the hospital, his main concern was the Rebbetzin’s welfare. “What will be with the Rebbetzin?” he asked. “In the kesubah I took upon myself to take care of her.”

Issy Morsel recalls Rav Kreiswirth once telling him about the “map” of the world which exists in Higher spheres, so unlike the one we know. “Here, New York and London and Paris are the big cities. But up in Shamayim? There, it’s Yerushalayim and Bnei Brak! The places where Torah is learned are the real ‘big cities.’ ” Rav Kreiswirth’s transformation of Antwerp into a place of serious learning must surely have earned it a place on the celestial map.

Rav Kreiswirth used to speak about Rav Akiva Eiger, who, as rav of Posen, took care to visit the sick of the town daily. “You can’t aspire to become an illui like Rav Akiva Eiger, but you can still aspire to emulate his gemilus chasadim,” he’d exhort. The same, perhaps, can be said about the Rav of Antwerp himself. If we can’t aspire to genius in Torah learning like Rav Kreiswirth, maybe we can still aspire to his genius in chesed.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 944)

Oops! We could not locate your form.