A Gentle Fire: The Legacy of the Chuster Rebbe

| March 28, 2023A rebbe who saw latent greatness in even the humblest of Jews

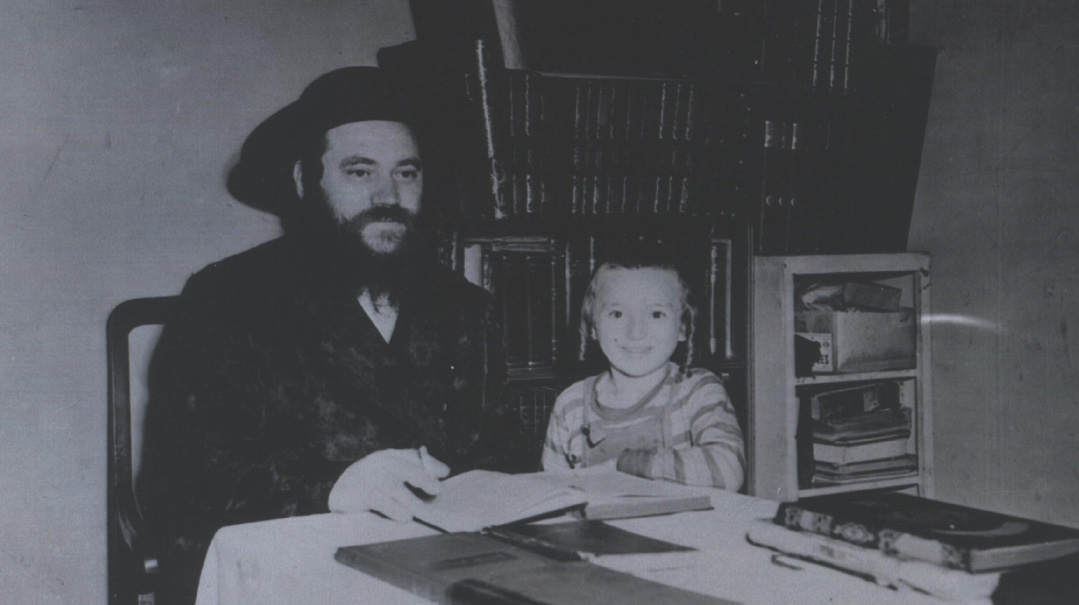

Photos: Yoely Strohli

Budapest, Hungary, in 1944 was a pile of red-hot coals about to ignite into flame. The country was on the brink of the German occupation that would massacre Hungarian Jewry. Against the backdrop of destruction, hiding in a bunker from the Nazis, the Chuster Rebbe, Reb Ahron Moshe Leifer, welcomed his first son into the world. The baby symbolized hope in the darkness, a new link to a distinguished dynasty that traced its roots to Rav Mordchele Nadvorna.

Rav Shmuel Shmelka Leifer, whose shloshim was last week, was my great uncle. He was born bein hachomos, between two worlds, and he embodied the passion of a previous generation with the approachability of a gadol raised in America. I always marveled at the dichotomy.

He was simultaneously a chain in the link of his illustrious ancestors, but also a member of the new generation, which had its eyes set on new frontiers. He carried within him the last flicker of a lost world, and also the sunrays of a new beginning.

He was my grandmother’s brother, but he treated me as a son, and from the age of 12, I spent every Yom Tov and many Shabbosim in his home. I was an American- born, Upper West Side kid who attended the local day school and didn’t speak a word of Yiddish, but none of that mattered to him.

He was a master at relating to those around him in a way that pulled them up to his level. His jokes and small talk lulled us into feeling a sense of relatability. And then he would take us on a journey, sweeping us in his fervor to the passionate Yiddishkeit of a previous generation.

Anyone who ever sat at his Shabbos table could sense his fire — bright, intense, and loving. He would close his blue eyes as he sang, his head lifted slightly upward, and his face would turn a bright shade of red. In those moments he was back in Europe with his ancestors, and their presence was palpable.

His father and grandfather up to Reb Mordchela Nadvorna were sitting next to him. On the other side was his uncle the Skolya Rebbe, and the Yampola Zeidas all the way up to the Baal Shem Tov. He was a fire set aflame by the souls of those he descended from.

And then, the very next moment, he would look at me and make a joke about Jim Bowie. In an instant he was transported right back to 21st-century America.

His davening during the Yomim Noraim, in the centuries-old nusach of his ancestors, was awe-inspiring. When he said “Haben yakir Li Ephraim,” with his distinct tune, everyone present felt eminently aware that they were a ben yachid of the Eibeshter. And then moments later we would sit down at the table and engage in small talk, as if he hadn’t just transcended to a different realm.

His “Vanitzak” at the Seder is etched in my memory. He would cry uncontrollably for 10 to 15 minutes, while humming a tune to himself. He was set aflame by the suffering of those he had encountered. And then only minutes later he would play peekaboo with grandchildren during Shulchan Oreich in order to keep them engaged.

Idon’t exaggerate when I say that not a day went by when he didn’t quote something from his father or grandfathers. He basked in the shadow of his ancestors’ legacy, and he was determined to carry on this heritage. And yet he was a forward-thinking mechanech. His yeshivah, Toras Chesed, was decades ahead of its time in numerous facets.

He would preach at every opportunity about the tragedy that occurs when boys aren’t accepted into yeshivos — well before it was in vogue to be speaking about the crisis of children who are left without schools. And his concern wasn’t limited to the public arena. He shared numerous pshatim at the Pesach Seder about these boys who were being forced out of the yeshivah system.

It wasn’t just talk; his yeshivah was filled with the “rejects” of every other yeshivah. But my uncle saw them as treasures.

One boy who had been asked not to return to his previous yeshivah in Europe was accepted to the Chuster Rebbe’s yeshivah. On the first day the Chuster Rebbe told the other boys that “today we have a new metzuyan coming to learn here all the way from Europe.” Their rejects were his metzuyanim, and they lived up to what he saw in them, eventually seeing it in themselves.

He took such pride in his talmidim, and whenever he met an old talmid, his face would light up. They were his nachas, and they brought him so much genuine joy.

The Gemara in Succah describes the saintly students of Hillel Hazakein, and says that the greatest of them, Yonasan ben Uziel, was so great that as he learned, the birds flying above him would be incinerated. Asked the Kotzker, “If this was the description of the students, what was the piety of the teacher, Hillel?” And the Kotzker answered, “Hillel was so great that as he learned the birds above him weren’t burned up.”

This was my uncle, a giant whose fire was so pure and genuine that instead of burning those who encountered it, it drew people in to be warmed by its beauty. He was the only person I have ever been around whose mere presence inspired, and made you aspire for more. His daled amos were imbued with the allure of his pure, fiery neshamah, and that was the secret of his chinuch methodology — to bring people closer.

His own kavod was irrelevant when it came to his talmidim. He could be seen sharing an ice cream cone with a talmid in camp if he felt it would bring the person closer to him.

His entire chinuch career was rooted in tremendous selflessness. Before going into chinuch, my uncle was a diamond dealer. He was successful in his business, achieving Torah u’gedulah b’makom echad. He would learn from early in the morning until early afternoon, only going into work around noon, and he also refused to work on Fridays.

And yet, when the opportunity arose to become a melamed in the Gerrer yeshivah, he gave it all up in an instant to be able to teach and inspire talmidim. He went from being a successful diamond dealer to living the rest of his life in debt, and he never looked back.

HE was willing to sacrifice anything — his time, money, or private space — for his talmidim. When one talmid lost his tefillin and was afraid to tell his parents, the Chuster Rebbe gave him money for a new pair out of his own pocket. Another talmid who accrued credit card debt that he was unable to pay off, had his debt wiped clean by his rosh yeshivah.

Tens of talmidim slept in his house over the course of the years, and I used to share the couch with other guests who had no home for Yom Tov other than their Rebbe’s. When one talmid was unaccounted for late at night, the Chuster Rebbe got in a car and personally searched the streets for him. His “self” was public property, accessible to anyone in need.

His lack of concern for his personal image applied to his beis medrash as well. On numerous occasions he was offered money to renovate the small, rundown beis medrash, and each time he refused, quoting Reb Mordchela Nadvorna, “A shul needs to have a door to the street, and a window to Shamayim.” He refused to use precious money that could be used to help people in need on refurbishing his beis medrash.

Finally, he once acquiesced, and agreed to accept a donation to remodel the shul, but ultimately decided against the planned renovation. He later recounted to me that for a few nights in a row he kept having dreams in which his father would appear to him. “He didn’t look happy with me,” my uncle recalled. He concluded that the reason for the dreams was that he’d agreed to take money for the shul.

When the mispallel refused to take the money back, my uncle used the money to pay off some of the yeshivah’s remaining debts and gave the rest to tzedakah.

IN close to 15 years of sitting at my uncle’s table, I can recall only one incident where he criticized me. We were having breakfast in the kitchen and he said to me, “The Chovos Halevavos writes that he had many reasons not to write his sefer, but he thought they stemmed from laziness, so he decided to write it anyway.”

The comment went right over my head. My uncle was constantly teaching and educating, and I didn’t think twice about it. Only hours later, when I reflected on our conversation, did it dawn on me that he had intuited that I had a strong lazy streak. This was his form of rebuke, delivered in such a subtle, gentle manner, that I didn’t even comprehend that it was aimed at me till hours later.

It’s not that he was oblivious to shortcomings; he simply made the conscious decision to look past them.

He made those around him feel like equals. On one Erev Pesach, a student came in late at night to sell his chometz to my uncle. He was sitting at the dining room table (he sat there the whole night Erev Pesach, accessible to anyone at any hour), and I was dozing off on the recliner in the corner of the room.

The student asked my uncle a certain question about chometz in his office building. My uncle gave the student a psak and then immediately turned to me, a 15-year-old boy half asleep, to ask if I thought he was right. I perked up and responded with what I thought was the relevant Gemara, and my uncle smiled in contentment and went on with his night. He was a fire who knew how to set those around him ablaze.

His singular goal was to be mashpia on anyone he could. While walking from his home on 48th street to his shul on 55th, he would say good Shabbos to every individual he passed. It bothered him when people wouldn’t respond with a good Shabbos — “You see another Jew walking down the street and you don’t greet him?”

If he passed someone he knew, he always stopped and said a good word, a story, a joke, a vort, something, so that two souls should not pass each other without sharing something between them. That was his whole life, a yearning to share his soul with others.

At the Seder night he had the minhag to pass out the simanim of the Seder plate as a segulah. In his later years, when his cognition had begun to decline, he began handing out the simanim in the middle of Maggid. Some present at the Seder began to encourage my uncle to wait until Shulchan Oreich to give out the simanim, and he began to weep uncontrollably. “I want to be mashpia brachos for Yiddishe kinder, why do I have to wait?” he asked plaintively.

This is the Chuster Rebbe’s legacy. He was a rebbe who wanted to share himself with others; a rebbe who sought to bring people close with his warm, soothing fire; a rebbe whose fiery davening was matched only by his bright, warm smile; a rebbe who carried on a legacy with humility and integrity, and yet was not afraid to innovate.

In so many ways, he was a rebbe who bridged two worlds. He was born amidst a blaze, he lived a life aflame, and he has left us all yearning for the bright, warm embrace of his gentle fire. —

Rabbi Noach Shapiro has a B.S. in psychology, a masters in social work, and he received semicha from RIETS. He is currently a member of the Beren Kollel Elyon and lives with his wife and daughter in Boro Park.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 955)

Oops! We could not locate your form.