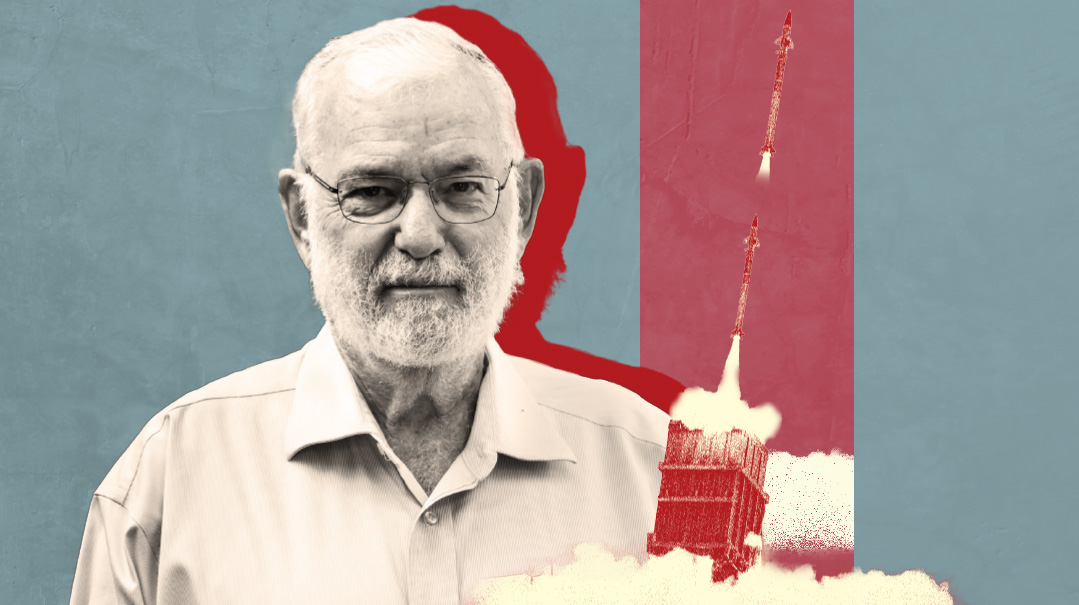

A Few Minutes with… Yaakov Amidror

| April 25, 2023Yaakov Amidror is a former national security advisor, Major General (res.)

Photo: Ariel Ochana

Preparing for War

Israel’s former national security advisor, Major General (res.) Yaakov Amidror, took to the airwaves last week to warn that the country’s confrontation with Iran is reaching a critical stage, and the stability that has reigned on the northern border with Hezbollah-controlled Lebanon may soon erupt. And US support in a wider conflict is not a given.

“We need to prepare for war,” he warned last Thursday on Israel’s Radio 103 FM. “We may reach a point where we have to attack Iran without US aid.”

Amidror sees two factors feeding the risk of all-out war: an increasingly emboldened Iran, which is driving the sudden resurgence in Hezbollah’s belligerence; and an increasingly disengaged, distracted United States, which makes its ally Israel more vulnerable. “Iran is more confident in itself. It has reached several agreements with Arab countries. The world is starting to look different.

“Meanwhile, this is not the same America we have known, in terms of its readiness, and the Iranians see that. The US has far more complex problems than the Middle East. The world looks at Israel differently.”

Amidror sat with Mishpacha for an in-depth discussion of Israel’s heightened security challenges.

We haven’t seen war in Israel’s north since the 2006 Second Lebanon War. But temperatures on the border have risen recently. Does this mean another war is becoming more likely?

The answer is a bit complicated. The world has changed since the last Israeli operation in Lebanon 17 years ago, as has the Middle East, with the United States perceived as increasingly reluctant to exert force or intervene in the region at all. It’s not that they lack the ability to do so, just the will.

In addition, Iran has just signed a series of peace deals with Arab nations, and is therefore feeling more confident. Iran is a large, powerful country with immense potential, and today no one can stop her from advancing in the nuclear arena.

Under these circumstances, I think one of the key strategic priorities of Israeli decision makers is to push off the conflict for as long as possible, something we’ve in fact seen. At the same time, we have to be aware that the danger of war exists and there’s no ignoring it. Especially since the capabilities of our enemies to the north haven’t deteriorated, as was once thought, but the exact opposite. We have to take into account in the most sober way that the time will come when we have to face them, on our initiative or theirs, or as the result of an escalation that neither side planned and both sides will regret.

I’ll remind you that neither side really wanted the Second Lebanon War either, and Nasrallah himself later stated that had he known how the conflict would turn out, he would never have started it. A misperception occurred then, too, as one side was sure that the enemy would react in a certain way, but the response turned out to be ten times as forceful.

This is a very sensitive issue, because it’s extremely difficult to predict where things will go. The “butterfly effect,” as it’s called, is an extremely important concept in the world of military strategy. For example, no one could have predicted that Saddam Hussein’s fall would indirectly lead to the success of ISIS, or that the Iranian nuclear deal would lead to intensive Russian intervention in Syria and an alliance between the two countries.

And this concept is even more crucial for a country like Israel, which, however powerful it may be, is still very small. We have to appreciate that we can’t control all the actors in the region, and so we have to avoid a situation where the State of Israel becomes vulnerable when circumstances change.

In your view, does the enemy perceive Israel as weak due to the political instability and the internal rift in the country?

Yes. There is an argument, which probably has a basis in fact, that Iran and Hezbollah view Israel’s internal divide as weakening the country, due to the threat by some protesters against judicial reform not to report for reserve duty. The sense is that Israel is reacting more hesitantly as a result of this, which was true in regard to the recent IDF response to Hezbollah’s penetration to Megiddo Junction, 100 kilometers over the border, with explosive materials.

The Israeli response, eliminating two Iranians in Syria, was next to nonexistent. It seems the Lebanese are feeling emboldened to do things they wouldn’t have tried before. But there’s also no ignoring the fact that Iran didn’t exactly respond to Israel’s action, which shows that the situation is more gray than black and white.

What really worries me is how strong Hezbollah has become since the 2006 war. We’ve also made strides since then, and developed capabilities that will surprise Hezbollah, but by now it’s clear that if we launch an operation in Lebanon, our home front will also suffer. And this is largely unprecedented, because usually it’s only towns near the border that take a hammering, and now serious concern exists that the entire country will be exposed to bombardment, from Eilat to Dan.

Will Hezbollah’s newly emboldened stance give Hamas ideas about destabilizing the security situation in the south?

Despite the hysteria exhibited by some news outlets, Hamas actually appears to understand the balance of power between the two sides quite well and knows that the Gaza Strip in general and Hamas in particular won’t have an easy time in the event of a large-scale operation there. And as a result, they’ve been careful not to ignite the area. The example that illustrates this best is that after the last time they fired Katyushas a few days ago, the IDF responded decisively, and they didn’t continue.

Why is Hamas so afraid of an Israeli attack, in your view?

It’s very simple — because they understand the balance of power between us; or they know that Gaza and Hamas will only suffer in an operation, and they don’t want to go there. As of today, they still haven’t finished rebuilding the ruins left by the last operation, and as long as they have more electricity than Beirut, there’s really no rationale for them to fight. So the probability of an operation in the near future is infinitesimal.

You seem to be qualifying your prediction as temporary. Do you anticipate an attack in the more distant future?

Life is temporary, but the strategy vis-à-vis Hamas is well known — to strike again and again, not in order to bring them down, but to deter. The State of Israel has never been interested in toppling Hamas, even though that’s well within its capabilities from a military standpoint. We know that the moment Hamas is no longer in control in Gaza, the vacuum will be filled by al-Qaeda or ISIS.

Israel’s view is that it’s better to have to deal with Hamas every now and then, rather than knocking them out and empowering other terrorist organizations with whom there’s really no talking to. Israel’s strategy is to give them a drubbing whenever the necessity arises, but never turn the heat up too high. And at the moment, the heat is quite low, so a large-scale operation in Gaza in the near future is not probable.

Besides that, the strong border fence that was built around the Gaza Strip, as well as the underground wall designed to prevent infiltration through tunnels, and on top of all that, the Iron Dome with its 90 percent interception rate, leave Israel well-fortified in the south. The risk to us is relatively small.

I repeat: If we embark on an all-out operation in Gaza, Hamas will be obliterated, and we’ll have two million people on our hands with worse chaos than exists today.

For all that, we’ve suffered many casualties on the Gaza front over the years. Is there a way that could have been avoided?

I’m pained by the death toll, but you can’t have a sovereign country without casualties. This is the price we have to pay for our independence. It’s a tough thing to say, but it’s the truth.

So you think that our policy over the years has been correct?

Sometimes more so, sometimes less so. Of course, mistakes were made, because after all, we’re only human, so there’s no point in getting into hair-splitting.

What about the commissions of inquiry founded after every operation — are you a fan?

Allow me to be skeptical of the ability of these commissions to arrive at accurate conclusions. I myself was once asked after a significant operation to review the intelligence collected before and during the operation. I arrived at the conclusion that the Military Intelligence Directorate made far less use of a certain resource than was called for.

When I spoke to the officers involved, I realized that my perspective was incredibly superficial — they were up to their necks at the time in two other complex missions, one of which was extremely urgent, and the other also important. They were torn between three different missions, and only in hindsight was it obvious which of the three should have been prioritized. I revised my report on the matter, but at the same time I felt uneasy, because all my conclusions were a product of my professional judgment, and who’s to say that my professional judgment was better than that of the officer in charge? Even in retrospect, I wasn’t necessarily more correct than he.

Sadly, much of the criticism that gets leveled by these commissions concerns violations of protocol, without understanding that protocol is only a means to an end and not an end in itself, and woe to a command system that doesn’t know how to break the rules when necessary.

At the same time, there’s no question that the State Comptroller is a valuable resource, especially with regard to corruption — if someone was benefiting financially from government decisions, you can’t denigrate or belittle the effort invested in that direction. But as noted, insofar as decision-making according to protocol, it isn’t always possible to reach conclusions, and one should proceed with extreme caution.

And what about our captives in Gaza? Unless I’m mistaken, you’re one of the authors of the notorious Hannibal Directive [for IDF forces to take extreme measures to avert the capture or kidnapping of soldiers].

At this stage we have two dead whose burials places are unknown, and two more who entered Gaza voluntarily and are being held by Hamas.

As for the Hannibal Directive, I was in fact the intelligence officer of the IDF northern command at the time of its drafting. The operations officer was future chief of staff Gabi Ashkenazi, and together we looked for a way to give our forces the clearest and most categorical instructions for how act in the event of an Israeli being captured by the enemy. And so we wrote the Hannibal Directive, which was approved by Major General Yossi Peled, the head of the command.

The Hannibal Directive was used during operation Protective Edge with the capture of Hadar Goldin at Rafiah. In accordance with the directive, the IDF fired heavily at the area, as a result of which Hamas reported heavy casualties.

But to the heart of the matter: do you think opportunities have been missed to return our captives?

No opportunity was missed. And I’ll remind you that we’re talking about bodies, not living people. It’s a really tragic situation, and my heart goes out to the families, but there’s a limit to what we can and should give in exchange for bodies.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 958)

Oops! We could not locate your form.