A Few Minutes with… Nathan Lewin

Under affirmative action, Jewish students lost most

Where Religion and Politics Mix

When trying to gauge the future impact of Supreme Court decisions, sometimes it’s wiser to look at what the justices didn’t say rather than what they did say.

Many religious rights groups hailed last week’s unanimous decision in the case of a Christian postal worker as a landmark ruling in favor of employees seeking accommodation of their religious beliefs in the workplace. The worker, Gerald Groff, had sued USPS, claiming it had failed to prove that his request for Sundays off would be costly to it, or inconvenient to the USPS or to his colleagues.

However, the Supreme Court merely returned the case to a US District Court for further consideration under a new standard that will now require an employer to demonstrate that granting the employee’s request would cause them “substantial hardship.” Under the previous standard, all an employer had to prove was that the extra costs would be de minimis, or minor. The Court declined Groff’s request to overturn a 1977 decision in TWA vs. Hardison that upheld the now defunct airline’s right to fire an employee — a Seventh-day Adventist — who refused to work on Saturdays. The final word has yet to be spoken on this issue.

In what might end up as a more historic decision, the Supreme Court severely limited if not effectively ended the use of affirmative action in college admissions. The Court voted 6-3 that admissions programs at Harvard and University of North Carolina violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that a student “must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual — not based on race.”

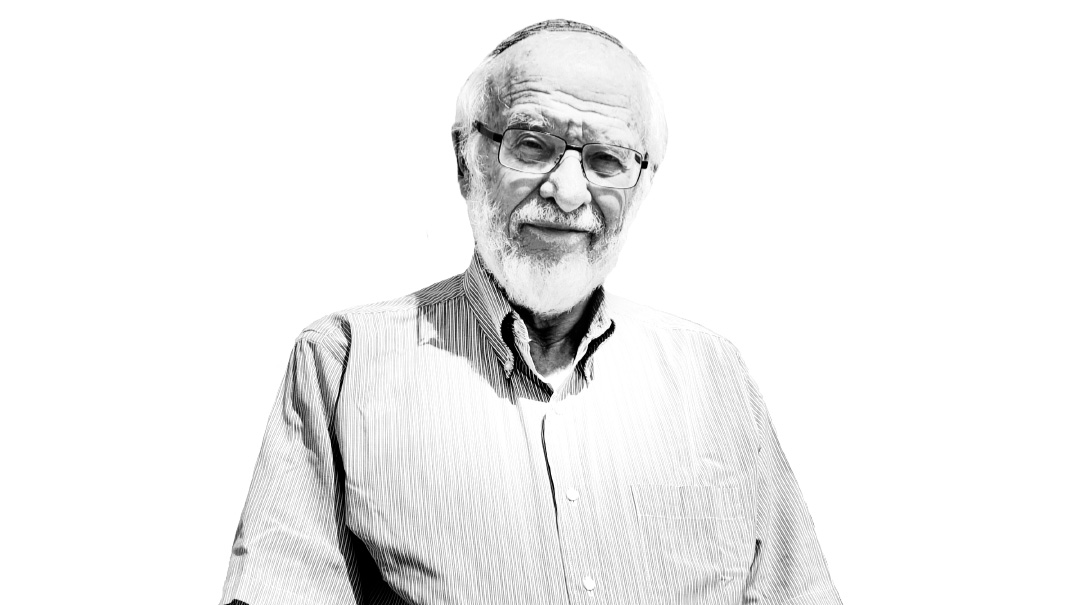

As is customary for almost 20 years following major developments at the Supreme Court, we checked in with Nathan Lewin, founder of the Washington-based law firm Lewin and Lewin LLP. Lewin has been Orthodox Jewry’s foremost advocate at the Supreme Court for the last half-century, having argued dozens of cases before the Court and forming personal relationships with justices, including Samuel Alito and the late Antonin Scalia.

We spoke on the phone just after these two rulings were issued.

“It takes a lot of interpretation is all I can say,” Lewin said. “Things are not always as simple as they appear sometimes in the media.”

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

If all the Supreme Court did in the Groff vs. DeJoy case was tweak the definition of employer hardship and then remand the case back to the lower court, what does this ruling change, and what protections will we have now that we didn’t have before?

Well, you’re very perceptive. Everybody is exhilarated and excited that the Supreme Court has addressed the de minimis statement made 47 years ago in TWA vs. Hardison, and they’re saying, “Isn’t it terrific?” It’s going to be so much easier for shomer Shabbos workers in the future. People are calling and sending me emails congratulating me, but I am quite frankly very skeptical.

I don’t view it as a victory if you consider what happens in the real world — or as I put it, in the trenches, where you’re dealing with people who are being told we’re not going to give you off for Yom Tov, or we won’t let you leave early on Friday because it’s inconvenient and it forces me to move other employees around. And when the employee says, “It’s my religion,” the employer says, “Let me talk to my lawyer,” and the lawyer who is paid by the employer can look at this latest opinion in the Groff case and say, “Well, that doesn’t apply here.”

How many employees go running to their own lawyers in those cases? They get denied, and frequently they either lose their job or they say, okay, I’ll work until the very last minute on Friday.

Considering the religious issue at stake, why didn’t the Supreme Court issue a broader ruling that would have better protected employees’ rights?

Because the Biden administration’s solicitor general [who argued on behalf of the USPS in the Groff case] reversed what Trump’s solicitor general had said. Trump’s solicitor general had said, in an earlier case that the court did not take, that you should overrule Hardison flat out. In came Biden and his administration, and his solicitor general said no, there is no reason to change the law because the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC] has done a good job of frequently [protecting workers’ rights] by telling [employers] you haven’t shown undue hardship. I also don’t think [Justice Samuel] Alito [who authored the unanimous opinion favoring Groff] really expressed what he believes. I think he was pushed to agree with an opinion of this kind because it was the end of the term, and because that way there would be a unanimous court decision, and because Justice Neil Gorsuch had suggested this kind of compromise during the oral arguments.

It’s interesting that if you listened to the running report that you have as the court decides cases, as I did yesterday at 10 a.m. as the court was issuing its opinions, Alito’s announcement was very brief. He didn’t explain the opinion he wrote, or that the court just issued, very substantially overrules what was said in Hardison. He just said very quickly that the court is reversing [the lower court opinion] and that was it.

Why should a Supreme Court that has three new Trump appointees be so solicitous of the arguments of a Biden administration solicitor general?

Oh, the court has been severely criticized as being too heavily conservative and Trump-oriented. And they knew that they were also going to be issuing a very controversial decision on affirmative action, in which they took the conservative view. Biden and all the progressives have been attacking them ever since they overruled Roe vs. Wade. People believe that the justices have tenure for life and therefore they can do whatever they like, but the justices are affected by how the public views the court as an institution, and them as individual justices, so here, they can issue a unanimous opinion in favor of religion, and everybody applauds them for it.

Practically speaking, what can people do if they feel their employer is not taking their religious considerations into account?

I operate as a very small practitioner with my daughter, and occasionally we get emails from people who are discriminated against, and I know what it’s like. To the extent that it’s possible, I may write a letter, but not everybody wants to go to court, and not everybody wants to go to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Yet that’s what this decision essentially does. It says if you go to court, or the EEOC, here is the complicated standard that ought to be applied. It should be more favorable to you than what used to be true. But that does not take it down to real life in the trenches.”

Let’s move on to the affirmative action ruling. The plaintiffs were Asian Americans who sued two universities, Harvard and the University of North Carolina. Does this now apply to everyone, everywhere, nationwide?

It affects everyone everywhere. It’s a constitutional ruling, so it affects admissions across the board, across the nation. If I think about the two decisions that came down yesterday, I have to tell you that it may be the affirmative action ruling that will be more helpful in the long run to Jews in the United States than the religious rights case that was decided.

How so?

From the very time it was initiated [in the 1960s], the effects of affirmative action did not initially impact Asian Americans, who are the ones that brought this suit to the Supreme Court, but it certainly impacted Jews. Before then, under the standards for admission to universities that applied when I was admitted to Harvard Law School in 1957, we had a very high percentage of Jewish students. Not Orthodox, but Jewish, because they were being admitted based on their merits, having done very well as undergraduates and on the law school admission test. They were able to excel in their law school courses. That’s the reason I managed to do what I was able to do in my legal career. I did not come from a wealthy family. I didn’t have any influence, but it turned out I was able, by my performance, to be viewed as someone very capable, and so the doors opened for me. Today, the statistics show that the number of Jews admitted to universities has dropped very significantly. Jews — and not just the Asian Americans who were the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Harvard and the University of North Carolina — are the ones who principally suffered and continue to suffer in admissions in the United States, under affirmative action.

Why is the ruling in the affirmative action case so much stronger and enforceable than the one in the religious rights case, or is it?

Because the affirmative action ruling says you may not consider race as a factor that qualifies somebody for admission. There’s been a lot written about how the universities are going to try to get around it by not talking about race, but talking about all other factors that are “color blind,” like whether the applicant came from a poor family or what neighborhood they were raised in. It may be that they can get around the decision that says they may not consider race.

But it seems to me initially, if you eliminate race as a factor, and you have a limited number of spaces open in the universities, there will be more Jews who will qualify for those limited spaces than there are today. You hear from parents of Jewish applicants who have phenomenal undergraduate records in high school and who are very highly regarded, and they’re not even put on the waiting list because all the spaces are taken by those who were favored because of race.

Does this ruling apply to the workplace or just to colleges and universities?

Colleges and universities. In the workplace, other factors also have similar considerations, such as DEI — Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. To the extent that they are followed in the workplace, that has its impact. Diversity, equity, and inclusion reduce the number of Jews, because it’s no longer a question of individual merit and ability, it’s a question of matching races and origins to this diversity, equity, and inclusion standard.

I found the announcement of the decision in the affirmative action case to be quite unusual, with so many justices reading their opinions from the bench. A few expressed some pretty strong personal feelings and not just legal opinions. Did you find that unusual, too, and if so, what does that mean going forward, for the unity of the court?

There are very strong conflicting personal opinions. Justice [Sonia] Sotomayor thinks that affirmative action is what got her to our present position and Justice [Clarence] Thomas, on the other hand, apparently gave a very moving and persuasive reflection on how he thinks affirmative action is harmful to black people. Justice [Ketanji Brown] Jackson supposedly was looking away the whole time that Thomas announced his opinion. It was very unusual.

Thomas has become very vocal in recent years, whereas he was silent in the past during oral arguments. This may be the first time, according to newspaper reports, that he announced a concurring opinion and that he expressed it in substantial detail.

Would you say that there’s serious polarization and dissension among the Supreme Court justices? If so, could it affect the functioning of the court, or are they professional enough to just take everything in stride on a case-by-case basis and move on?

I think they’re professional enough to take everything in stride and move on. They’re working together as an institution, recognizing that they have very sharp differences of opinion. This is the old [Ruth Bader] Ginsburg / [Antonin] Scalia analogy. Even though they had very sharp differences of opinion, they were very good personal friends. That happens in terms of people working together, even though they may have different views. Whether it’s within a presidential cabinet or any other organization, people may disagree on certain basic principles but respect the fact that each has a deeply held, rational position. I think they get along, and they’re doing the best they can for the country.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 968)

Oops! We could not locate your form.