A Few Minutes with…Eitan Regev: Boosting Chareidi Employment

Hybrid employment schemes may be key to chareidi jobs

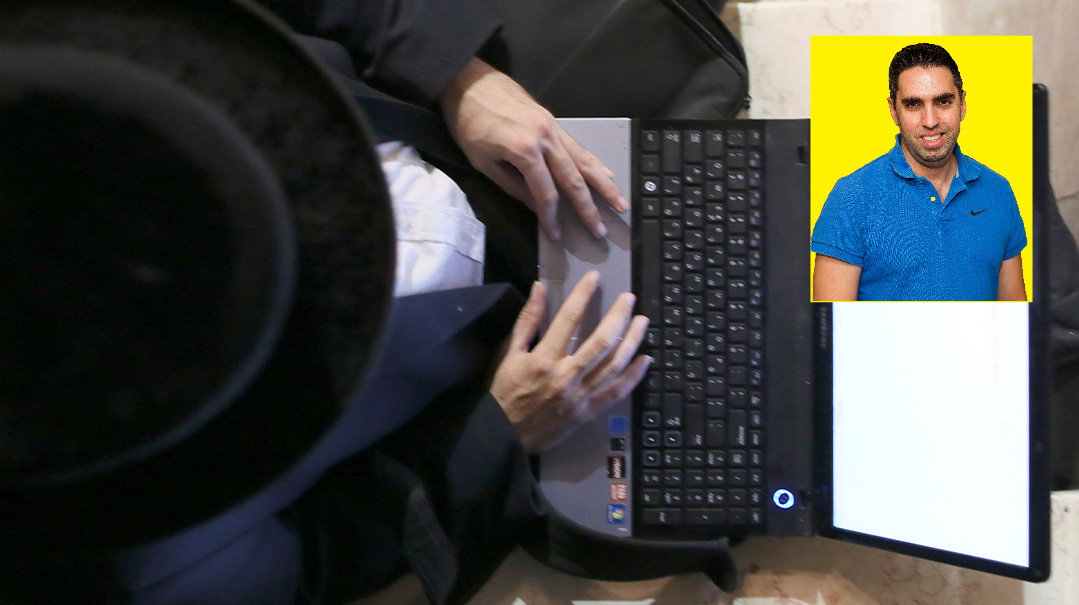

Many Israelis either unfamiliar with or hostile to the chareidi world endlessly point to the community’s low workforce participation rates, mainly among chareidi men and how that eventually will spell doom and gloom for the economy as the chareidi population grows. But what the doomsayers often fail to grasp is that underemployment — or unemployment — is not always a matter of personal choice. Sometimes it’s due to a lack of choices. In a recent interview with Dr. Eitan Regev, the vice president of data and research for the Haredi Institute for Public Affairs, he detailed many impediments to higher chareidi employment that the next government must work on. His ideas are even more relevant now, since chareidi parties will be in charge of the Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs, which oversees job training and employment opportunities.

Dr. Regev is a leading data scientist, with specific expertise in the chareidi economy. A former research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute and senior researcher at the Taub Center, he earned a PhD in economics from Hebrew University. He has also served as an economist in several government offices, including the Ministry of Health’s budget division. His research encompasses many fields, including labor productivity, optimal taxation, vocational training, and higher education.

There is a big gap in earnings between chareidi and non-chareidi families. It’s at least NIS 9,000 per month, on average. Is there a way to level the playing field in a market economy?

There are some objective obstacles that stem from differences in human capital [the economic value of a worker’s experience and skills], but to focus only on that is to miss a lot of opportunities to remove other obstacles in a way that chareidi society could support.

For example, we’ve discovered that the inability of chareidi women to commute to jobs dramatically influences their ability to earn higher wages. About one-third of chareidi women work close to home or walk to work. That limits their search radius for finding appropriate work that corresponds to their training. Finding new ways to enable chareidi women to work in hybrid employment, by commuting to a more distant workplace two or three times a week and working from home the other days, would greatly increase the probability of their working in a profession that fully takes advantage of their training.

Where do you see this hardship manifest itself the most?

In Beit Shemesh, we see chareidi women who are unable to commute outside the city. The employment opportunities within the city are very limited and don’t necessarily correlate to their training. So most of the opportunities within the city are low-wage jobs. Vocational training institutes were not even willing to open up shop in Beit Shemesh. Some talented women are looking to work and want to fulfill their earnings potential, but because of their relative geographical isolation, it is hard for them to do so.

Beit Shemesh is a big city now. Why can’t it offer this?

One of the solutions that we advocated for the Beit Shemesh municipality was to try to attract more high-paying employers from outside the city who would be willing to accept hybrid employment schemes for chareidi women. If they are not willing to locate an office in Beit Shemesh, at least they might agree to let those women work from home or from workspaces in Beit Shemesh three days a week and suffice with having them coming to their main branches, say in Raanana or Givatayim, the other two days. The post-Covid era opened the opportunity for such employment models.

Here’s another problem. Only 30% of chareidi women have a driver’s license. So even within Jerusalem, chareidi women are mostly limited to employment opportunities near their neighborhoods. And the way Jerusalem is laid out, there are only a few important employment centers — Har Hotzvim, the center of town, and Givat Shaul. But look at where most of the chareidi neighborhoods are situated and what the commuting time is on public transportation within the city. For these women to work in one of these business centers but live in chareidi neighborhoods, they will never get back in time to pick up their children from kindergarten.

What about men?

For many men it’s a more significant problem, because there isn’t even a proper training mechanism. Most vocational training programs for men are what I might call “pirate” programs or unsupervised programs. So this opens the gate for many companies that want to benefit from this industry and sell dreams to many young men who want to earn a proper living. Even when we speak about more advanced professions like high tech, we know that many vocational training schools claiming they can train chareidi men properly for high tech or other professions have been taking shortcuts. We have learned that many of those programs are simply failing because the training isn’t thorough or long enough, and the content isn’t relevant enough to what employers need. And the linkage to the world of employment is weak.

Can you be more specific?

The impact of the first job you land after your training has a dramatic impact on the rest of your career. If your first job is not in a field that you studied for, in the vast majority of cases, you will never work in the field you studied for, and your training will become irrelevant. That is true for men and women. And those people will be much more likely to be dismissed from the workforce sooner. We saw that with women in Bnei Brak. Women whose first job was not in their field study exited the workforce sooner.

What’s the solution?

We need to create a mechanism that links women and men to employers during the vocational training process. I researched this issue, specifically with a small sample of chareidi women who studied in academia, but it could also apply to vocational training. Among chareidi women who studied in academia and interned with an employer during their studies, 40% were hired into full-time jobs for those employers. That’s four times higher than the general population.

This is something that is being done in most vocational training systems in the world, between 40% and 80% in most European countries. But in Israel, only a negligible percentage of all vocational training includes on-the-job training. So for chareidi men, we need to create and institutionalize a proper vocational training system whose content and quality, and even the composition of fields of study, are both supervised and guaranteed to be relevant to the needs of the labor market.

The Central Bureau of Statistics cites figures that about 6% of all Israelis own businesses or are entrepreneurs. Is this higher or lower in the chareidi sector?

We conducted major research about this issue, trying to understand why chareidi businesses are not earning as much as non-chareidi businesses. We discovered that the share of independent workers and business owners among the chareidi sector is quite similar to that of the general population, perhaps a little less. However, the share of chareidi businesses that manage to grow beyond the scale of two or three workers is really small, so they don’t grow in size or revenue.

We found many reasons for this phenomenon. One of the reasons is a fear of growing and dealing with the bureaucracy involved with that, such as dealing with the authorities, and hiring and paying accountants and lawyers. It’s a scary process, and business owners need access to the right information about that and how to form and maintain a business.

We found that business literacy is a big issue, as well as dealing with the digital world. It’s a fact that most chareidi businesses only appeal to the chareidi sector, which limits their growth potential. And also, the average income of their customer is lower, which also limits the business’s income. Most chareidi men who do open a business or a shop in a chareidi city find that the demand is smaller because their customers’ ability to pay is smaller.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.