A Cool Wind Blows in from the East

Annexation could damage "cold peace" with Jordan

While much of the chatter over annexation has focused on the threat to relations with the Palestinian Authority, the European Union, and perhaps even the United States, Israel’s neighbors to the east and south are also raising their diplomatic voices in protest. And the consequences of a fallout with Jordan and Egypt will be graver than any rise in tensions with faraway Brussels.

The greatest risk lies with Jordan, which signed a peace treaty with Israel 26 years ago. Amman cooperates with Israel in two areas vital to its existence — water and gas. But beyond the pipelines that transfer those life-sustaining commodities, there has been little progress on other areas of mutual concern, including a joint Aqaba-Eilat airport, a Red Sea–Dead Sea canal, restoration of the Jordan River, and agricultural development.

Indeed, in recent years Israel has given up on the possibility of further breakthroughs in this “cold peace.” Maybe it’s because of the two million–plus Palestinians who live in Jordan, who make up about 22 percent of its population, and are very vocal in their opposition to the Jewish state. Or maybe it’s because the Jordanians are happy with the status quo: Jordan gets a steady water supply and Israeli security cooperation from the peace agreement. Ironically, Israel is Jordan’s only secure border.

According to Israel’s ambassador to Jordan Amir Weissbrod, “Without Israel, Jordan would have a water problem, and their electricity supply would also be endangered.”

In addition to whatever trouble annexation might stir up, King Abdullah II of Jordan is also concerned about his general standing in the wider Middle East. Since 1967, the Hashemite kingdom has maintained custodianship over the Temple Mount and other Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem. However, Turkey and even Saudi Arabia are now attempting to gain a foothold at his expense.

The peace treaty with Israel gives Abdullah the breathing space to deal with regional threats such as the Syrian civil war (more than 650,000 Syrian refugees are now living in Jordan) as well as tribal frictions at home. From Israel’s perspective, the peace treaty neutralizes a threat along its longest border and significantly increases its strategic depth. The stability of the Hashemite royal house is also important to Israel as a bulwark against the rise of a hostile regime that might resume tensions.

Nonetheless, over the past few years, both sides have taken steps that have weakened relations. The latest incident is related to the Tzofar and Naharayim enclaves, two areas near the Israeli-Jordanian border that were leased to Israeli farmers for 25 years with an option for renewal. Last October, King Abdullah announced that he would not extend the leases. The unofficial Jordanian explanation was talk in Israel about annexing the Jordan Valley and other areas.

However, external influences also played a part in that decision. The Jordanian king isn’t happy about President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or the move of the US embassy. Abdullah had asked Trump to leave Jerusalem up for negotiation between the parties. America’s move, widely interpreted as one-sided in support of Israel, led the king to position himself as a defender of the Palestinians and a strong Arab leader bent on reclaiming Arab land from Israelis.

The most complex issue, which bears on all the others, is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. King Abdullah supports the two-state solution in principle and opposes Trump’s “deal of the century,” although he expressed readiness to take a deeper look at the matter after being pressured by American and Saudi officials. The Palestinian issue is critical for the king domestically as well, as he has to deal with a large Palestinian population whose discontent can threaten the stability of the regime. The concern in Jordan is that annexation of large parts of Judea and Samaria could lead more Palestinians to emigrate to Jordan, further destabilizing the kingdom. For this reason, resolution of the conflict is of the highest importance for the Jordanian royal house.

Hand in Hand

Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, signed 40 years ago, could also be described as a cold peace. In this case, Egypt is being less vocal about the consequences of annexation, but Cairo believes Israel is taking advantage of the economic weakness of Egypt and the rest of the Arab world to carry out its agenda.

Dr. Chaim Koren, former Israeli ambassador to Egypt, explains to Mishpacha that since Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s rise to power in 2014, Israel and Egypt have maintained close cooperation on security and strategic issues. The foundation of that cooperation is an understanding that Iran and Islamist terror organizations pose a common threat, and that quiet and stability in the Gaza Strip is in both countries’ interests.

Egypt’s position as a mediator in cease-fire agreements arranged between Israel and Hamas is critical. Egypt at once reaps international recognition for its peacekeeping efforts and ensures that its interests are protected in any agreement reached.

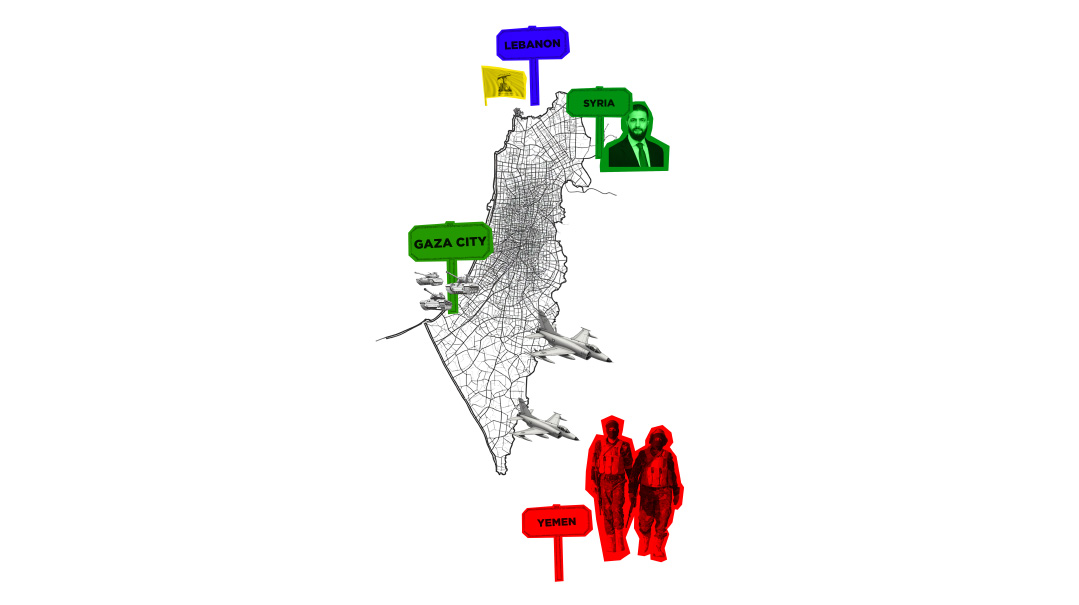

Anger Stoked in Lebanon In the midst of the annexation debate, Lebanon has sunk to a new low. Since October, the lira has lost 70 percent of its value, a record. While its citizens battle the coronavirus, the nosedive of Lebanon’s currency has resulted in many Lebanese losing their life’s savings.

As a result, demonstrators have come out to the streets in force. The protests are aimed against the country’s ruling elite, Hezbollah, and its sponsor, Iran. Unrest has spread throughout the country, though the movement is centered in the capital, Beirut. Rioters have repeatedly clashed with security forces and vandalized banks and commercial centers.

Iran and Hezbollah have blamed Israel and the United States for stoking the unrest, and Jerusalem is paying close attention. As Israel inches toward annexation of some settlements, its northern neighbor might use the move as a pretext to launch a war — and distract its citizens from their economic misery in the process.

Iran, too, is facing difficulties in Lebanon and neighboring Syria.

In 2015 Iran sent thousands of Revolutionary Guard soldiers to Syria, but after suffering heavy casualties, it began downscaling their presence in the country. Today, Iran’s presence in Syria is mainly confined to military advisors, and that’s not surprising: Tehran wants proxies to do its dirty work and spare Iranian blood.

The main forces employed in Syria over the past few years have been Shiite militias — tens of thousands of local and foreign fighters. But now the fighting in Syria has died down. The pockets of resistance to dictator Bashar al-Assad have dwindled and Iran will likely continue withdrawing its soldiers from the country. But Iran still poses a threat. Reports of its demise in Syria are likely premature.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 815)

Oops! We could not locate your form.