A Chassidic Label for Rav Leibel

| January 30, 2024The unusual trajectory of the life of Rav Leibel Eiger (1816–1888) was unforeseen at the outset

Title: A Chassidic Label for Rav Leibel

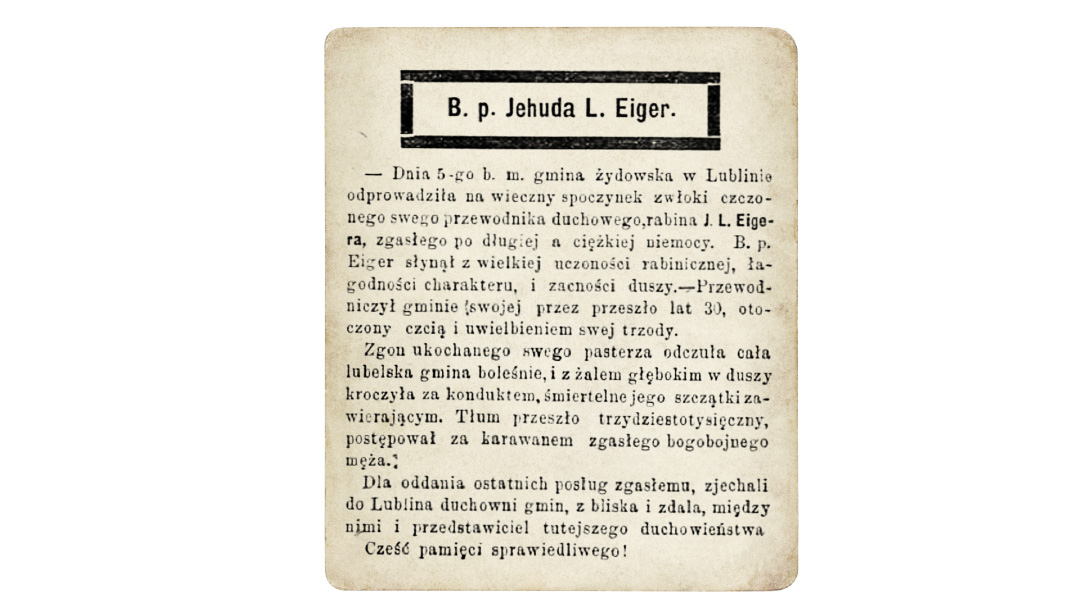

Location: Lublin, Poland

Document: Izraelita (Warsaw)

Time: 1888

I was asked by the holy and honorable Rav Yehuda Leib Eiger shlita, to evaluate his practice of engaging in lengthy, holy preparations prior to performing a mitzvah, as was the way of the early chassidim, in order to properly discharge the mitzvah obligation in kedushah and taharah. This understandably takes a significant amount of time. When he is asked to serve as a mohel and sandek for a bris milah, he engages in lengthy preparations and only executes the mitzvah after midday chatzos.…

His question is therefore twofold: Is it permitted to engage in this practice, or must he perform the mitzvah earlier, without the requisite preparation? And is it permitted for a baal bris to request that he serve as mohel, since there are other mohalim in Lublin who would perform the bris in the morning?

I answer as follows. It is a simple and obvious fact, on which all the poskim concur, that it is preferable to perform a mitzvah in the most ideal fashion. It is therefore a mitzvah min hamuvchar when it is carried out after a thorough preparation.…

This holy individual is well known as one whose thoughts and deeds are always completely l’Sheim Shamayim. His focus on his preparations throughout the time leading up to the mitzvah actually fulfills the requirement of zerizin makdimin l’mitzvos. Zerizin in this context means to be a zariz in one’s preparation for the mitzvah. That his actual performance of the mitzvah is delayed by several hours isn’t due to negligence or unnecessary delay, but rather because of his zerizus in the proper preparations.

There are many proofs to this, but there is no need to cite them, for this is a davar pashut. It is therefore proper for him to continue in the way that he is accustomed, and not only is it permitted for the baal bris to have him serve as the mohel, it is in fact preferable to do so.…

I was asked by the Rav Hakadosh shlita my opinion in halachah and Torah on this matter, therefore I’m stating unequivocally my opinion that this tzaddik should continue in his ways performing the mitzvah with kedushah and taharah, and those who respect this will receive honor from Heaven…

—Letter from Rav Tzaddok HaKohein of Lublin to his close friend

Rav Leibel Eiger, circa 1864

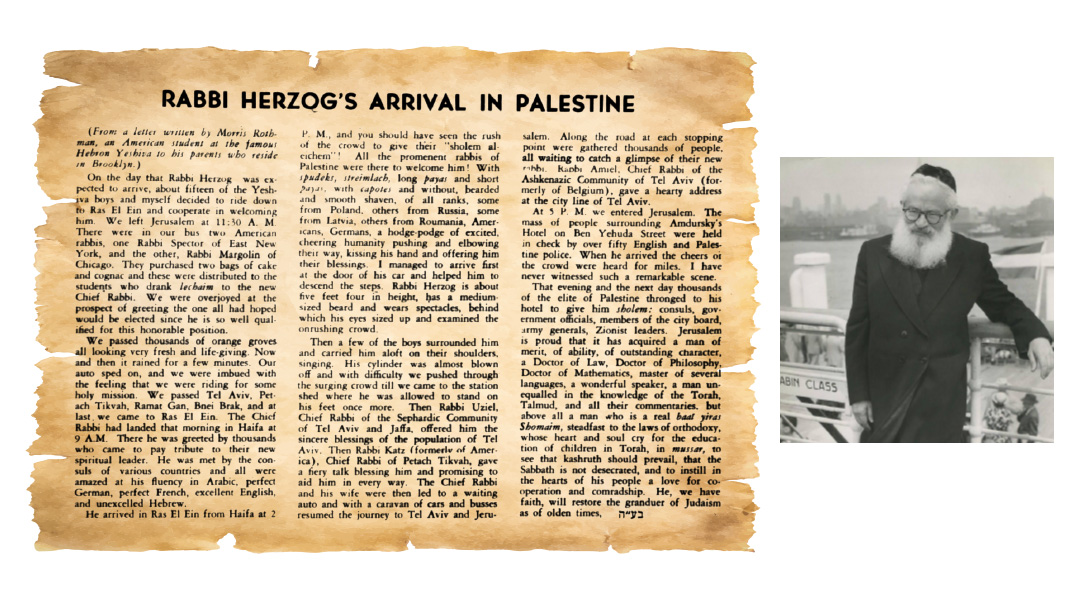

The unusual trajectory of the life of Rav Leibel Eiger (1816–1888) was unforeseen at the outset. Scion of one of the most aristocratic rabbinical families in Europe, his illustrious father was Rav Shlomo Eiger. He grew up in Warsaw and later studied in the yeshivah in Pozen (Poznan) under his renowned grandfather Rav Akiva Eiger. Rav Leibel would later recall with yearning the years spent in the shadow of his grandfather, and expressed regret that he didn’t develop an even closer relationship with him. Following his marriage into a wealthy family in Lublin, he settled there and remained for the rest of his life.

As a youth in Warsaw, he had been a student of the city’s famous Torah scholar Rav Itche Meir, the future Chiddushei Harim of Gur, and under his sway was first exposed to chassidus. This was later reawakened when he was a young man living in Lublin, and he made the life-changing decision to travel surreptitiously to Kotzk.

When Rav Leibele Eiger arrived in Kotzk for the first time, he was dressed befitting someone of his stature, in silk socks, a fur shtreimel, and an expensive cloak. Rav Hirsh Tomashover gave him the typical rough welcome that was customary in Kotzk, and relieved him of his shtreimel and cloak, which he proceeded to hand to another chassid, whom he instructed to purchase some whiskey with the proceeds of the sale of the clothing.

Rav Leibele complained about the treatment he received to the Kotzker, who then told Rav Hirsh to retrieve the clothing and return them to Rav Leibele. The Kotzker explained, “Either way, he won’t remain here for long.”

And so it was, for Rav Leibele Eiger later left Kotzk with Rav Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izhbitz. Rav Leibele Eiger’s father, Rav Shlomo Eiger, was concerned with the new chassidic path of his son and sent a special emissary to Kotzk in order to ascertain what his son’s ways were in his new environment…

—Emes V’emunah 624

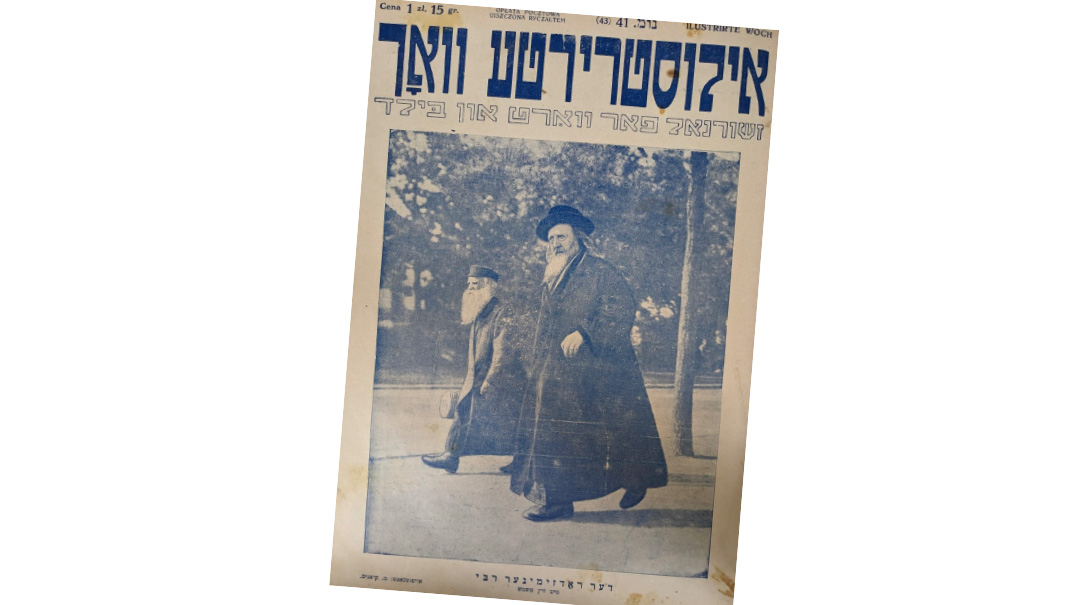

Rav Leibel Eiger followed Rav Mordechai Yosef Leiner to Izhbitz upon the latter’s departure from Kotzk in 1839, and he emerged as the leading follower of the Izhbitzer. Upon the Izhbitzer’s passing in 1854, while many followers stayed with his son Rav Yaakov Leiner, who established the Izhbitz court in Radzyn, others prevailed upon Rav Leibel to become their leader.

He subsequently gained a following in Lublin, and together with his dear friend and fellow Izhbitz talmid Rav Tzaddok HaKohein, led the Lublin branch of the Izhbitz dynasty until his passing. Several volumes of his Torah were published posthumously under the titles Toras Emes and Imrei Emes.

Ich Bin an Einekel

Rav Leibel was succeeded by his son Rav Avraham Eiger and his friend Rav Tzaddok HaKohein. As Rav Tzaddok was childless, Rav Avraham and his progeny carried the torch of the Lublin chassidic dynasty until the Holocaust. One of his sons, Rav Shlomo Eiger, was a menahel and member of the shilton ruchani at Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin following the passing of its founder, Rav Meir Shapiro. A grandson named Rav Avraham Eiger survived the war by escaping to Shanghai, and reestablished the Lublin court in Bnei Brak, where it remains to this day.

An Answer for Rav Akiva Eiger’s Question

“Rav Leibele Eiger asked the Kotzker to advise regarding his grandfather Rav Akiva Eiger’s concern about him missing the zman tefillah due to his davening at a late hour. Rav Leibele emphasized that his grandfather would only be satisfied with an answer that is grounded in a din and not in the derech of chassidus. The Kotzker responded that he should tell his grandfather that the Rambam states that if a worker spends his entire work shift sharpening the ax he needs to carry out his job, then all of his actions are considered in line with his job description.” —Sefer Emes V’emunah 135

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 997)

Oops! We could not locate your form.