A Blood Libel in New York

| April 22, 2025The blood libel was leveled collectively against the Jews of Massena

Title: A Blood Libel in New York

Location: Massena, New York

Document: New York Daily News

Time: Fall 1928

The true hero was Rabbi Brennglass of sainted memory. Had Massena’s rabbi been of a different character, one shudders to think what might have happened. His magnetic, piercing eyes, neat Van Dyke beard, and steel-gray hair (partly hidden by an old-fashioned high yarmulke) made him an impressive figure. He knew what had to be said and was not afraid to say it.

He had dressed down the state trooper who had come to his house to summon him to the police station, and, later on at the police station, he spoke to the mayor and the troopers in no uncertain terms, He was a man of surpassing moral and physical courage, and his message came through in that volatile situation.

I recall that after his beautiful rendition of Kol Nidrei (he was a talented baal tefillah, too) he addressed the congregation. Though I was only a child, I remember his charge to the community to stand up as proud Jews and staunch Americans — against all anti-Semitism. He inspired all of us, old and young, and we emerged from the synagogue that night with our heads high and physically unafraid.

—Samuel J. Jacobs, The Blood Libel Case at Massena: A Reminiscence and a Review

Few believed that Jews could fall victim to the blood libel, a benighted medieval superstition, in the United States, an enlightened, 20th-century Western democracy where freedom of religion was enshrined in the Constitution. But that is unfortunately what happened.

Massena, New York, a small town on the Canadian border, was a growing industrial center toward the end of the 19th century. It drew French Canadian, Irish, and Italian immigrants — all Catholic — soon joined by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. The native Protestant population feared being overwhelmed, and suspicion of all newcomers was palpable in the town. The Jewish population was relatively small, about 20 or so families, and had organized into an Orthodox shul, Adath Israel. By 1920 the shul had purchased and renovated its own building.

Two years prior, in 1918, the shul had hired a shochet, Hebrew teacher, chazzan, and spiritual leader — Rabbi Berel Brennglass. He led Massena’s Jews for 23 years until his wife passed away in 1941 and he retired to New York City. Rabbi Brennglass (1876–1966) was born in Trakai, Lithuania, which was then part of the Russian Empire, and studied at the famed yeshivah of Slabodka. Following a stint in Wales, he came to the United States in 1915.

His health issues took him to upstate New York, and shortly thereafter he was offered the multi-purpose pulpit in Massena. In his capacity as rabbi, teacher of the community’s youth, chazzan, and shochet, he was paid $23 a week by the community, reduced to $20 during the Great Depression. During this time, Rabbi Brennglass did everything he could to uphold Orthodoxy and tradition. By all accounts, he was beloved by his congregants, no small feat in the rough environment that greeted most immigrant rabbis in the United States during that era.

One Saturday afternoon two days before Yom Kippur in 1928, a four-year-old non-Jewish girl named Barbara Griffiths got lost in the woods near her home on the outskirts of town. The frantic parents called the volunteer fire department, which employed several members of the notorious Ku Klux Klan. A search conducted until nightfall produced no results. The girl was missing.

New York state troopers then took over the search, and at around midnight, a malicious rumor began to spread through the town. A major Jewish holiday was approaching, and back in Europe, it was often believed that the Jews engaged in a blood ritual with a Christian child as part of their holiday ceremony. Could it be that the Jews of Massena had kidnapped Barbara Griffiths for nefarious purposes?

The state police questioned two problematic and non-representative members of the Jewish community. One was Willie Shulkin, son of Adath Israel president Jacob Shulkin. Willie was mentally impaired, and unable to provide coherent testimony, but upon his return home, his father grew alarmed and called a meeting of community leaders in his home late Motzaei Shabbos.

The next morning, the police questioned an assimilated Jew named Morris Goldberg. Despite there being a large Orthodox community in town, the police interrogated the completely ignorant Goldberg, a Jew in name only, about Jewish ritual and religion. According to the officers who questioned him, Goldberg did give a vague impression that these sort of rituals could be possible in the Jewish religion.

On Sunday morning, Erev Yom Kippur, Mayor Gilbert Hawes decided that the rumors were substantial enough to haul the rabbi in for questioning. A state trooper was dispatched to the rabbi’s house at about noon. Rabbi Brennglass’s actions likely saved a situation that was rapidly spiraling out of control. First, he rebuked the trooper for disturbing him on the eve of the holiday with such a nonsensical claim. He then sharply scolded him for even having the chutzpah to consider such a medieval, baseless, and completely false charge of blood libel. Finally, he declared that he refused to accompany the trooper to the police station for questioning as if he were under arrest, but would arrive voluntarily later in the afternoon. Stunned by the rabbi’s confidence, the trooper complied.

Shortly thereafter, the rabbi strode into the police station where the mayor and police officers were waiting to question him. Before they had a chance to pose a single question, Rabbi Brennglass began angrily berating them for believing the fallacious rumor, and demanded to know what contemptible individual was responsible for spreading it around town. He stated emphatically that anyone who believed Jews capable of such awful crimes should be ashamed of himself, especially in a liberal democracy such as the United States in the middle of the 20th century.

Upon completing his peroration, he abruptly turned on his heel and left. The astonished mayor and officer didn’t have a chance to ask a single question. The exact wording of the rabbi’s speech may have been exaggerated over time, perhaps bordering on apocryphal, but his courage in standing up for the reputation of his community and the entire Jewish People is unquestionable.

At 4 p.m. that afternoon, little Barbara Griffiths, very much alive this entire time, meandered out of the woods onto the road near her home and was spotted by townspeople, who promptly returned her to her worried family. By the time local Jews made their way to shul for Kol Nidrei later that evening, the worrisome saga was over and the potential danger had passed. There were some lingering anti-Semites who claimed that the Jews had only returned her after their cover was blown, and that her having been found alive actually proved their guilt. But then again, one can’t reason with anti-Semites.

Although no violence was perpetrated against Massena’s Jews, the episode did reveal some disturbing trends. That a blood libel could take place in the United States, publicly supported by New York state troopers and the town’s mayor (who may have even threatened an economic boycott) was a shocking reality check to immigrant Jews who had come seeking a new life in the land of freedom. In addition, it was very telling that no individual Jew was charged or even thought to be a suspect with a reasonable motive. The blood libel was leveled collectively against the Jews of Massena. This wasn’t what American justice was supposed to represent.

The entire troubling incident was a sobering reminder that even in their new home, full of hopes and dreams for a better future, Jews still faced challenges. And the ugly shadow of anti-Semitic blood libels could find them even on the other side of the Atlantic.

Day of Atonement

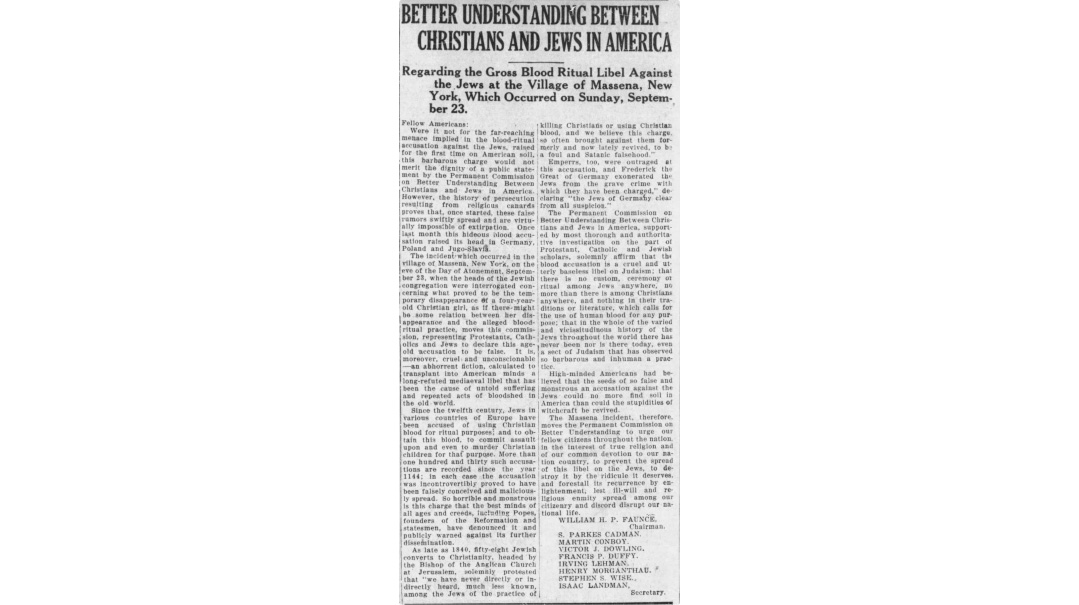

Perhaps most concerning was the deafening silence from their non-Jewish neighbors, government officials, local media, and everyone else. No apology was forthcoming. Only when the incident subsequently drew national attention and media scrutiny, followed by demands by the American Jewish Committee and the American Jewish Congress for a formal apology and a denunciation of the city’s leaders, did the mayor and state police issue a public apology to Massena’s Jews and the wider American Jewish community.

Millennium of Libels

The blood libel or ritual murder charge, a canard hurled at Jews for a millennium, cost Jewish life, property, and safety in communities around the world. Believed to have first been promulgated against the Jews of medieval England with the story of William of Norwich in 1144, it was generally associated with Pesach, and the corresponding Christian holiday of Easter.

But there were instances of blood libel at all times of the year, and in proximity to other holidays as well. The false ritual murder accusation spread to continental Europe in the 12th century, and migrated east over the ensuing centuries. It had tragic consequences well into in the 20th century, such as the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, the infamous Mendel Beilis trial in 1912 in Kiev, and the postwar Kielce pogrom in Poland 1946.

This column is based on the research and writings of Dr. Yitzchok Levine.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1058)

Oops! We could not locate your form.