The Warrior Finds a Rebbe

A conversation with Reb Romi Cohen z"l several years back. A lion has fallen.

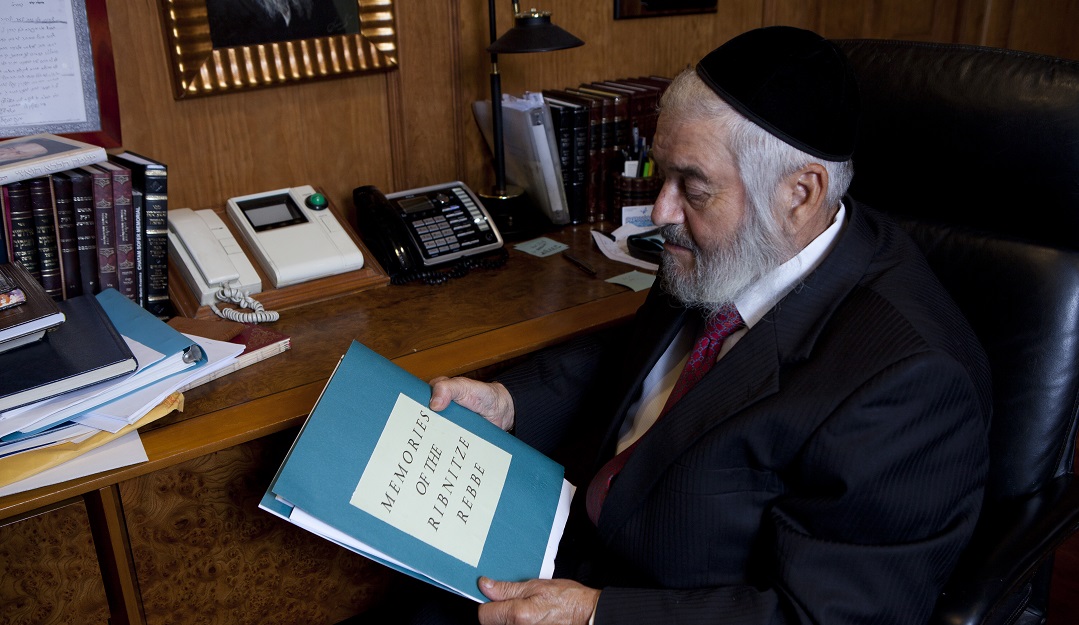

(Photos: Amir Levy)

Y

ou can make out two of the great storylines of Rabbi Romi Avrohom Cohn's life by observing him. More than 70 years after the war, he still radiates the strength of a forest warrior; and in his deft motions, you see the precision and swiftness of an expert mohel.

Those two storylines continue to live on in his two classic works: Bris Avrohom HaKohein is a definitive sefer on the halachos and minhagim of bris milah (Rabbi Cohn, one of New York’s foremost mohelim, represented the American Board of Ritual Circumcision at recent governmental bris milah hearings), while The Youngest Partisan (Artscroll/Mesorah) is the captivating tale of a daring teenager who sneaked across borders and fought the Nazis in the forests.

Yet perhaps his most cherished manuscript is one that has yet to be published, but holds the secrets of a nearly forgotten rebbe and miracle worker who had no children to carry on his legacy. When Rabbi Cohn speaks of his rebbe, he seems to shrink, all that power replaced by humility, the resourcefulness giving way to awe.

He waves a sheaf of papers, stories following each other in a flowing river of astonishment. When he created this manuscript, it was with an urgency that if he wouldn’t get the record down, if he couldn’t capture the magic of the tzaddik, tomorrow would be too late. In a few years, who would remember? Who would retain the legacy of the Ribnitzer Rebbe?

“I realized that people might never believe such a person really existed, that he lived the way he did and was able to bring salvation to so many on a personal level. So I started writing, if only to remind myself.”

A New Rebbe

In Rabbi Cohn’s office in the basement of his Boro Park home, the security devices — cameras, grates, and alarms — give the well-appointed room a bank-vault feel.

A child of Pressburg, the city that spawned the glorious path of the Chasam Sofer (whose burial place Rabbi Cohn was instrumental in saving), Rabbi Cohn, 86, wasn’t raised as a chassid. When he eventually settled in New York after the war, he joined the Vienner kehillah — where he’s a member until this day — but as he became a sought-after mohel in various chassidic courts, he grew close to several admorim.

Commercial success added to his popularity, and his trips to Jerusalem were marked by the receiving line of a gvir in his hotel lobby. On one visit back in 1970, Rabbi Cohn was solicited by the director of a Yerushalmi cheder in search a new heating system so that the cheder yingelach might learn in relative warmth and safety. Rabbi Cohn didn’t have much time to listen to the pitch, as he was heading home the next day, but as is his custom, he still responded generously.

The next day, as Rabbi Cohn was rushing through his last-minute errands before traveling to the airport, the Yerushalmi returned.

A bit exasperated, Rabbi Cohn asked why he was back.

“I want to show you something special. Come with me and you won’t be sorry.”

Rabbi Cohn explained that he had no time for sightseeing.

“Listen, trust me, this is a way of thanking you,” pressed the Yerushalmi. “I’m going to introduce you to a new rebbe.”

Rabbi Cohn laughs sheepishly at the memory. “I told him I had plenty of rebbes in New York, that I wasn’t looking for more.”

But the Yerushalmi persisted, not letting up until Rabbi Cohn agreed to join him on a trip to a small apartment in the Sanhedria neighborhood.

“There was a long line, a big commotion, but no one could really tell me much about the tzaddik behind the door.”

Shared Vessels

In Russia, Rav Chaim Zanvil Abramovitz had been known as a “gitter Yid,” someone whose brachos and tefillos always seemed to bear fruit, but he liked to be called simply Chaim Zanvil, preferring the title of friend to that of rebbe. He lived an ethereal existence; as a young man he’d trained his body to accept the dictates of its soul. He fasted regularly, refusing to take his daily meal until after Maariv, which was often well after midnight.

In the frigid Russian winter, he would be seen walking with an ax. The tool was his constant companion, handy as it was in cracking thick layers of ice, so that he might immerse himself in the water underneath. He would relentlessly hammer away until he succeeded in breaking through the frozen water. The Rebbe would be standing in subzero temperatures with sweat pouring from him, so great was his exertion for this mitzvah. It is told that during those frozen Russian winters, he would return home from tevilah with his entire body covered in ice.

Even non-Jews had great respect for him; KGB officers would come with their wives and children to receive blessings from Chaim Zanvil, who could be found learning in shul, his feet in a bowl of freezing water.

And now this figure who’d traversed the forgotten paths of Russia and Romania, offering encouragement and blessing, welcoming children in to the bris of Avraham Avinu and bolstering the faith of their parents as the last of the great rebbes to remain in Russia, was a free man who was given permission to emigrate to Eretz Yisrael.

He sat in the crowded Sanhedria apartment, surrounded by a coterie of devoted gabbaim trying to keep the masses away from a tzaddik unused to the trappings and pressures of a formal court. But Rabbi Romi Cohn, with his newfound Yerushalmi connection, was allowed in.

The Ribnitzer, as he was known, raised his holy eyes and looked at the visitor from Boro Park; he stood up and embraced him. Rabbi Cohn wrote about this first meeting — among his reams of text on his relationship with the Ribnitzer — so that he, and others, would never forget:

Then the Rebbe started to tell me of everything that had befallen me, recalling events and stories of long ago as if he’d been standing there. I understood then that my neshamah was connected with that of this tzaddik. “Remember this?” he asked me, mentioning various moments in my lifetime.

That evening Rabbi Cohn returned to America; not long after, word spread that this mysterious tzaddik was coming as well.

“People vied for the zechus to use him as mohel for their sons. But he needed milah tools, so someone contacted me. I joined the Rebbe at the bris he was performing and shared my keilim.”

Rabbi Cohn, expert mohel, looked closely. He felt that the Rebbe hadn’t completely removed the skin, that the job was somewhat imperfect. From the notebook:

I obviously couldn’t say anything, so I resolved that I would visit the family the next day, ostensibly to check on the baby, but really, to finish the job. The next day, I went to the child’s home, and they recognized that I’d assisted the Rebbe by the bris and let me in. I was astounded. The bris was perfect. It was extraordinary.

From there, Rabbi Cohn went straight to the Rebbe. As he writes:

When I came, he was in the middle of davening Minchah. He was serving as chazzan, and he didn’t see me come in, but when he completed chazaras hashatz, he suddenly turned and walked toward the corner, where I was standing. I figured that he wanted to wash his hands in the sink before continuing, so I moved aside, but he stopped by me. “Nu? Hust gezehn? Bist tzefriden? You saw the bris? Are you satisfied now?” Then he went back to continue davening.

Ashes and Tears

The Rebbe settled in Boro Park, and Rabbi Cohn became a member of the Ribnitzer’s inner circle.

An inviolable part of the Rebbe’s schedule was Tikkun Chatzos. The Rebbe would sit on the floor with ashes on his head, surrounded by candles. Only once he was alone would the weeping begin, wails loud and intense enough to melt the heart of anyone within earshot. It was the eternal cry of Klal Yisrael trapped in galus, expressed in the agonizing sobs of this elderly Jew. “If you heard those cries, then you knew the Rebbe in a different way,” says Rabbi Cohn.

When the Rebbe was finished, the tears and ashes had mingled, and he would be sitting in a puddle of thick mud.

Rabbi Cohn made some minor renovations in the Rebbe’s private room. “I was worried that the stone floor was too cold for him to be sitting on, so I built a concrete floor and added heating, so that he would be warm and the many candles wouldn’t present a fire hazard.”

The Rebbe never formally thanked his chassid, but from then on, the relationship shifted.

“Reb Avrohom,” the Rebbe would say fondly, “iz mein bester gitter freint, my dear, beloved friend.”

Shabbos left slowly, reluctantly, in Ribnitz. From the notebook:

The Rebbe would finish Melaveh Malkah so late that my only concern would be to make my daily shiur, at 4 a.m., on time. He couldn’t let go of Shabbos. Late one Motzaei Shabbos, the Rebbe sat at his table and suddenly reached out toward the flame of the burning candles. Holding his hand in the fire, the Rebbe told me quietly, “This has no power over me.”

In the notes, black letters dance predictably along white pages, but if you look closely, you can hear the hiss of fire, smell the melting wax.

Rabbi Cohn taps his notebook. “These are just words… The Rebbe didn’t use words. He was alone, because no one else could see what he saw. We accepted it, we understood that he lived in a different dimension.”

For example, when the Rebbe would sit in Brooklyn or Los Angeles and say, “What’s doing here?” his people knew that “here” referred to Eretz Yisrael, while “what’s doing there” meant America. He saw a different reality than they did.

My host indicates a particular paragraph from the memoir:

I was sitting with the Rebbe one day and a woman came in, crying profusely. Her husband was paralyzed — unable to move out of bed, she said between sobs.

The Rebbe listened and asked, “Vi shteit ehr?” which literally means “Where is he standing?” The Rebbe meant to ask for his location, but the woman misunderstood.

“Rebbe, he can’t even move a single limb, how could he possibly be standing anywhere?”

The Rebbe, who preferred to speak as little as possible, indicated that she should write down the address and then motioned for his coat and stood up. I drove him through the streets of Brooklyn to the address she’d written. When we arrived at the home, the Rebbe didn’t hesitate. He hurried up a long staircase and turned right at the top, as if he had a map. He headed directly to the room where the patient lay, immobile.

“Nu, stand up already, genig shoin, it’s enough,” the Rebbe commanded him.

Two tears fell from the eyes of the patient. “I can’t move any part of my body,” he said.

“Nu, privt, try,” the Rebbe insisted.

The patient sat up. Wide-eyed, he moved his legs toward the floor. By the time the wife, who’d followed us home on foot, arrived home, her husband was coming to greet her. Two weeks later, he joined us at the tish.

Another “miracle” story:

A visitor from Eretz Yisrael handed the Rebbe a kvittel. The Rebbe quickly scanned it and said, “Your father should have a refuah sheleimah.” The visitor looked confused and indicated the kvittel, assuming the Rebbe was mixing him up with someone else. When the Rebbe repeated the very same brachah, the visitor hurried to investigate. His father back in Eretz Yisrael had sustained a heart attack moments earlier, but would have a refuah sheleimah.

Not all the stories preserved on the pages tell of miracles. In one, Rabbi Cohn recalls driving the Rebbe home from a bris in Manhattan:

The Rebbe was upset. He kept repeating, “A bris uhn a seedah, a bris without a meal.” The Rebbe was surprised. “I don’t understand. The baal habris has parnassah, why didn’t he make a meal?”

I didn’t understand what the Rebbe meant, for in fact, there had been a lavish seudah following the bris. Finally, I realized what the Rebbe meant. There had been a seudah, but it hadn’t been fleishig — and that bothered the Rebbe enough that he considered it a bris without a meal!

Miraculous tales of Alexei, the Baal Shem Tov’s wagon driver, occupy a prominent place in chassidic lore. Rabbi Romi Cohn tasted some of that wonder at the wheel of an oversized black Cadillac.

Late one afternoon, we had a bris in Monsey, but we had to rush to a pidyon haben in Brooklyn before nightfall. It was already just around shkiah, and I didn’t think it possible. To make things more difficult, as we were leaving the home of the baal simchah in Monsey, a neighbor stopped the Rebbe to share a tale of woe about his daughter, whose husband refused to give her a get. The unfortunate woman had been chained for more than ten years.

The Rebbe listened, ignoring my entreaties that we had to hurry. Finally, the Rebbe spoke. “She’ll go free — either he’ll give the get or the other way [meaning with his death].”

The Rebbe headed to the car; it was already growing dark. “Don’t worry so much,” he told me, “we’ll make it.”

I began to drive. The Rebbe closed his eyes, turning his head to the back seat and saying “shalom aleichem” three times. Then he began to turn his cane in front of him, as if controlling the car. A little sports car suddenly appeared in front of the Cadillac and I swung into the lane behind it. Traffic seemed to open before the tiny vehicle and we didn’t let up, following it as we passed through traffic all around like a gale wind. The Rebbe seemed to be dozing, but as we pulled up in front of the Brooklyn destination, the Rebbe sprung awake and opened the door. “Nu, we made it on time, burech Hashem,” he exclaimed.

The next morning, the father from Monsey came to tell the Rebbe that his son-in-law had agreed to give a get.

“Ich veis, I know,” the Rebbe said quietly.

The Grocer’s Gratitude

Eventually the Rebbe left Boro Park, moving to a series of locations including Miami, Sea Gate, Los Angeles, and Monsey.

The Rebbe’s devoted chassid, his “bester gitter freint,” saw less of him. “There were different periods, different gabbaim, some of whom understood the Rebbe and some who didn’t. It wasn’t always easy for him,” says Rabbi Cohn.

But there was one of the Rebbe’s confidants, Rabbi Cohn recalls, named Reb Yitzchok Volf Herman, whose devotion to the Rebbe was unparalleled. “He slept on a hard bench outside the Rebbe’s room, always nearby in case the Rebbe needed something. I once asked him why he was so dedicated, and he told me a story about when he was proprietor of a small grocery store in Solesh, Romania.”

And Rabbi Cohn wrote down the story for the next generations:

He told me about one of the other chevreh, Reb Avrohom Lemberger, who had also lived under Communist rule. This Lemberger was a war hero, and so he was given the privilege of holding a job that would allow him to have Shabbos off; he worked as a traveling salesman. Each month, his route took him through Solesh, where he would stop off at Reb Itzik Volf’s store and buy enough kosher food to last him through the following weeks.

One month, Lemberger didn’t appear. Reb Itzik Volf noticed, but wasn’t sure what to do. That night, he had a dream in which an unfamiliar Jew said, “Go, Reb Avrohom needs your help.” He ignored the dream, but it repeated itself the next night. Reb Itzik Volf told his wife about it, and she started to push him to travel, to find out where his friend was. He told her that he had no passport, so she prodded him to get one. The following night, the unknown visitor appeared yet again, with the same message.

Reb Itzik Volf had his friend’s home address, and he set off for Lemberg. He arrived in the early morning and went directly to the apartment, where Reb Avrohom’s wife — who’d heard his name from her husband — welcomed him. He asked if he might have a cup of hot coffee before they spoke, but she apologized and explained that she’d just run out of coffee. He was weak with hunger, and requested a piece of bread or a cracker. She told him that she had just used the last crumbs. He understood that there was nothing in the house and excused himself. He managed to find food on the black market, which he purchased and brought to her home.

The three young children came to life as he lay the food down on the table; they ate with gusto, and the hostess apologized. “My children are usually very well-behaved and polite,” she said, “but they haven’t eaten in three days. Please excuse them.” Then she told her visitor how her husband has been suspected of carrying an infectious disease, so he’d been quarantined in a local hospital. There was no telling if and when he would be released, even though there was nothing wrong with him. Reb Itzik Volf headed over to the hospital and bribed the guards, earning his friend’s release and accompanying him home.

Later on, Reb Avrohom confided in his savior that his family had been starving, but his wife was too bashful to ask for help. In gratitude, he wanted to repay Reb Itzik Volf by introducing him to a special person. They boarded a train, and Reb Avrohom took his visitor to the town of Ribnitz, Moldavia. He knocked on the door of a humble apartment, assuring Reb Itzik Volf that he was about to meet a tzaddik. The door opened, and Reb Itzik Volf beheld the figure who’d appeared in his dream; the same saintly eyes and radiant face, down to the missing button on his coat.

Reb Itzik Volf completed his tale. “How can I leave such a man, even for a moment?”

No Explanations Necessary

Without speaking, Reb Romi stands up. He passes by the pictures of his rebbi, Rav Yosef Grunwald of Pupa, and his rebbe, the tzaddik of Ribnitz, and heads toward the corner of the room.

Like the secrets safeguarded in his heart, there is a treasure hidden behind the barely discernible door. He slides open a small paroches and removes a sefer Torah.

“This was the Rebbe’s.” He holds it tenderly. Like the scroll, he seems to be saying, which carries so much more than parchment and ink, the Rebbe who appeared human was filled with uncontainable light.

He shakes his head. On Isru Chag, the day after Succos, it will be 20 years since the Rebbe’s passing, but really, the tzaddik of Ribnitz was never really here.

He shows me one of his final entries:

The Rebbe was a tremendous talmid chacham and always wanted to meet Rav Moshe Feinstein, but it never worked out because of the disparity in their schedules. One night, when Rav Moshe was already hospitalized, the Rebbe suddenly asked the gabbai to drive him from Monsey to Manhattan. The driver had no idea where to go, but the Rebbe directed him to the hospital entrance, and then they made their way through the empty lobby. They asked no one for instructions, but the Rebbe went up in the elevator, stepping out on a particular floor and walking down the hall to a room. He stopped in the doorway and looked in.

There lay Rav Moshe, his eyes open, though he was unable to speak. The Rebbe and the Rosh Yeshivah locked eyes, neither of them speaking for several minutes. Then, without a word being exchanged, the Rebbe turned and left.

Months later, Rav Moshe was niftar.

Like many of Rabbi Cohn’s stories, it has no explanation, but it needs none; the story itself is the explanation. Not only don’t we know everything about this exalted figure, we know almost nothing.

Other than in the Divine register, there is no record of those years in Russia, when a lone Jew crossed the freezing landscape and lit fires, reminding his people that their Father had not forsaken them. And later, in the land of the free, there were crowds and cameras and commotion, but still, the Rebbe was somewhere else. Alone.

In Rabbi Avrohom Cohn’s notebook, diligently preserved stories live on. Though they can’t tell the full story, they evoke a glorious time, a time when he touched the extraordinary day after day, a time when he merited to serve an angel, a time when the tzaddik looked at him with warmth and love.

And greeted him — a dear, beloved friend.

(Originally featured in The Record Keepers Supplement, Succos 5776)

Oops! We could not locate your form.