Everyone’s Rosh Yeshivah

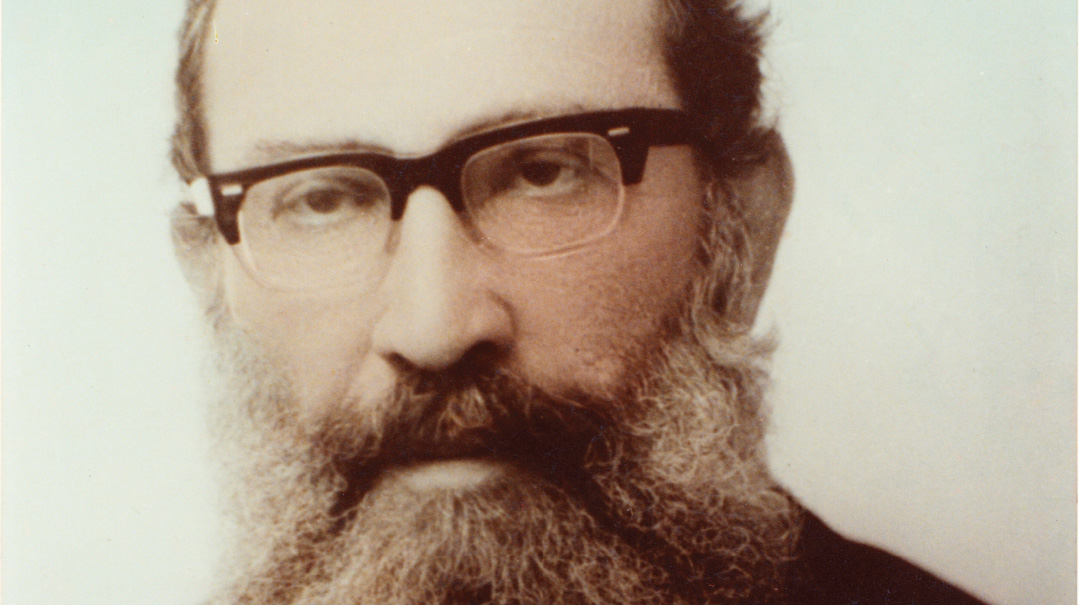

| May 11, 2021More than four decades after his passing, talmidim, assistants, and the American hosts of “everyone’s rosh yeshivah” share their personal memories of Rav Shmuel Rozovsky

It was a frigid morning in late January of 1978.

A throng of men stood together in the arrivals hall at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York, eyes trained on the door. Suddenly, the doors swung open and a tall, dignified rabbi appeared. Instantly, the waiting crowd locked arms, began a celebratory tune, and began to dance toward him.

A weakened Rav Shmuel Rozovsky approached the joyous crowd with surprise in his eyes and waved them off, but they remained undeterred. The leader of the group, a veteran talmid, clasped Rav Shmuel’s hand warmly and whispered some words into his ear. Slowly, the great Ponevezher Rosh Yeshivah began to smile. He beckoned the group to a nearby seating area where they crowded around him in silence. No matter that he’d just concluded a grueling flight, no matter that his health was precarious, no matter the strange surroundings. The Rosh Yeshivah was here, and his students were thirsty for his words.

There in JFK airport, he settled into the familiar melody. “Zugt der heilige gemara…”

Rav Shmuel Rozovsky was born in the Eastern Europe of 1913, but his name remains on the lips of virtually every yeshivah bochur in 2021. His seforim are essentials, his insights the foundation of so many of today’s popular shiurim. He was one of the prime pillars of the postwar rejuvenation of the yeshivah world, a product of Europe’s finest yeshivos who helped transform a tiny group of undervalued yeshivah bochurim into Bnei Brak’s mighty Torah bastion.

Rav Shmuel was born in Grodno, where his father Rav Michel Dovid Rozovsky served as the chief rabbi. He studied at the local Sha’ar Hatorah Yeshivah and became a prized student of Rav Shimon Shkop. Rav Shmuel also studied with several older students in Grodno, and one of the earliest and most influential was Rav Yisroel Zev Gustman.

Rav Gustman recalled how Rav Michel Dovid Rozovsky begged him to learn with his prodigious young son. He soon realized that this boy was special way beyond his years. “By the time he reached bar mitzvah, there was no one like him in the yeshivah. We would learn 17–18 hours a day. He knew every single one of Rav Shimon’s shiurim — literally all of his shiurim.”

As an 11-year-old prodigy, young Shmuel would engage the older bochurim, like Rav Chaim Shmulevitz (who had a teaching position at age 18 in the yeshivah) and Rav Nissan Eckstein, who became the rav in nearby Kuźnica. Rav Shmuel “sat in the dust of their feet and drank thirstily the words of each and every one.” And they in turn loved him.

Rav Gustman recalled how Rav Shimon Shkop — in whose home he was a ben bayis — once asked him, “What’s with Rav Michel Dovid’s son? He’s a feiner bachur’l? Does he understand learning?”

To which Rav Gustman responded, “I can tell the rav that this is a gaon’isher kind [a child prodigy].”

“Do you enjoy learning with him?” Rav Shimon asked.

“Immensely! I have great pleasure from our learning,” Rav Gustman replied.

“What do you mean when you say he’s a ‘gaon’isher kind?’” Rav Shimon then asked.

“I’ll tell the rav what I mean,” he replied. “Illuyim [geniuses] are characteristically a bit meshugeh. But this boy is a geshmacker! He’s so measured, so calm; he has such beautiful middos. The description illui doesn’t suit him, because he’s already surpassed all the illuyim!”

Filled with Light

Rav Shimon Shkop’s legendary derech halimud was to have a decisive impact on young Shmuel’s learning — and ultimately on his teaching style. In 1934, Shmuel Grodner (as he was known) joined the Mir Yeshivah, where he studied with his friend Naftali Beinish Wasserman Hy”d, whom Rav Shmuel would later describe as a younger version of his illustrious father, Rav Elchonon.

Afternoons were spent studying with one of the prewar luminaries of the Lithuanian yeshivah world, Rav Yona Karpilov Hy”d. In addition, he had the opportunity to learn with Rav Leib Malin, Rav Henoch Fishman, and his former rebbi in Grodno, Rav Chaim Shmulevitz, who had since joined the Mir.

It was 1935 when Rav Shmuel’s world began to turn upside down. He received an emergency telegram summoning him back to Grodno to see his dying father. He made it home several days before his father’s passing, and after the shivah he decided to remain with his newly widowed mother. A few months later, he received more bad news in the form of a dreaded draft notice from the Polish Army.

In an effort to avoid the dangerous Polish military service, he and his close friend Rav Zalman Rotberg decided to immigrate to Palestine. The rav of Petach Tikvah, Rav Reuven Katz, facilitated their receiving coveted immigration certificates, and upon arrival in 1936 the duo settled in Petach Tikvah, where they studied at the local branch of the Lomza Yeshivah.

Rav Shmuel was a great “catch” for the yeshivah and he was soon asked to lead an elite chaburah. One of those who noticed his skills in explicating Torah was the Chazon Ish, who after a single visit foresaw the role Rav Shmuel would one day play in the development of Torah in Eretz Yisrael. “He’s going to be the rosh yeshivah of the next generation,” he predicted — and made it a habit to rise thereafter whenever the young prodigy entered his abode.

When the Brisker Rav first arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1941, he expressed his disappointment: He could find few Torah scholars with the requisite knowledge for a proper Torah discussion. When Rav Shmuel came to converse in learning with him, he was finally satisfied. “I have been waiting for a bochur like this,” he said delightedly to his son Rav Dovid.

After his marriage to Esther Frank, daughter of Yerushalayim’ s Chief Rabbi Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, Rav Shmuel moved into the home of his father-in-law on Rechov Malachi, not far from the Brisker Rav’s home on Rechov Press. He began learning with the Brisker Rav every Erev Shabbos. Years later, Rav Dovid Soloveitchik told noted Brisker dynasty biographer Rabbi Shimon Meller how his father described Rav Shmuel’s entrance to their home: “The whole house would be filled with light!”

Yeshivah of Seven Talmidim

It wasn’t until the end of the Holocaust that the Jews in the Holy Land began to learn about the utter devastation it had wreaked. The scope of the destruction brought a general feeling of defeat; few believed that Europe’s glorious Torah world could ever be restored. Leaders and laymen alike were broken and hopeless.

The Ponevezher Rav, Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, strongly disagreed with the prevailing sentiment. Back in Europe, he’d had a large family and prominent yeshivah. Even though both were cruelly destroyed, he refused to succumb to the prevalent despair and was determined to rebuild.

Rav Kahanamen dreamed of a massive yeshivah, situated on an abandoned hill on the outskirts of Bnei Brak. To realize his dream, he hired Rav Shmuel Rozovsky, the young genius who’d been transplanted by a Heavenly Hand from Grodno to the Holy Land. As founder and Nasi, Rav Kahanemen brought Rav Shmuel to serve as rosh yeshivah, a relationship that would change the course of history

Though he was later joined by Rav Dovid Povarsky and Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach, Rav Shmuel was to be the yeshivah’s primary rosh yeshivah, and his shiurim and derech halimud were to be a central influence in the postwar yeshivah world.

The Ponevezh Yeshivah opened on 4 Kislev, 1943 in a shul on Rabi Akiva Street in Bnei Brak, and Rav Shmuel immediately began to commute from his home in Yerushalayim to deliver shiurim. Yeshivas Ponevezh opened its doors with its first mashgiach, Rav Abba Grossbard, and seven talmidim: the brothers Gershon Edelstein (future rosh yeshivah of Ponevezh) and Yaakov Edelstein (future rav and Av Beis Din of Ramat Hasharon); Chaim Friedlander (future mashgiach of Ponevezh); Uri Kellerman (future rosh yeshivah of Knesses Chizkiyahu in Kfar Chassidim) as well as Rav Shmuel’s nephew Yehudah Leib Frank, Moshe Ziskind and Zelig Privarsky, with whom Rav Shmuel was acquainted from Grodno.

The yeshivah was housed at the Heligman Shul and the bochurim utilized a nearby dilapidated hut for meals, which they shared with some of the recently arrived yaldei Tehran (a group of Polish children who’d escaped the Holocaust via Iran). The physical conditions were awful, yet Rav Shmuel used his contagious simchas hachayim and love for Torah to create a positive atmosphere that was conducive to learning. When Rosh Yeshivas Hanegev Rav Yissachar Mayer was once asked why bochurim were attracted to Ponevezh amid such appalling conditions, he replied, “Ponevezh had Rav Shmuel! He spent the whole day with the bochurim and infused the learning with such a geshmak!”

Rav Yaakov Edelstein described those memorable early shiurim:

“When Ponevezh opened with Rav Shmuel giving his daily shiurim, he would learn each and every word of the Gemara and Tosafos with us. There were shiurim on Friday too. Each shiur lasted for approximately two-and-a-half hours and covered the material daf by daf. He focused on the main points in order to develop our minds and knowledge of the Ketzos Hachoshen, Rav Akiva Eiger, Rav Chaim Brisker — all the significant points of the daf. We started Bava Metzia in Kislev, and by the end of the winter zeman we had reached the middle of perek Hazahav in the daily shiur. Daf by daf, from the beginning! In the summer we started perek Eizehu Neshech and by the end of the zeman we had completed (perek) Hashoel until daf kuf!”

Rav Berel Povarsky, currently rosh yeshivah in Ponevezh, still vividly remembers the force of Rav Shmuel’s shiurim: “Rav Shmuel’s absolute clarity could not be found anywhere else in the world. He was the rosh yeshivah of the entire generation!”

Anyone who attended his shiurim, Rav Berel noted, couldn’t bring himself to attend a shiur anywhere else. “For two years, I never missed a single shiur. Once, I was running a high fever. My father [Ponevezher Rosh Yeshivah Rav Dovid Povarsky] came to check on me, and although he always encouraged me to draw the maximum that I could from Rav Shmuel, this time he pleaded with me to stay in bed. I told him that I couldn’t bear to miss the shiur. Seeing that I intended to go, he went to Rav Shmuel and asked him to forbid me to come, and both of them actually came to my room to try to dissuade me.”

The young Berel wouldn’t give up though. Cunningly, he asked his father, “Tell me, Tatte, what would you have done in such a situation?”

“What I do is something else,” Rav Dovid replied.

“In that case,” Berel said, “I’m going to shiur.”

And he did. “Missing Rav Shmuel’s shiur wasn’t an option,” he explained. “It wasn’t even a nisayon for me, because every time I came out of a shiur, I felt like a new person!”

Every Shiur Like New

Rav Avraham Pam, the rosh yeshivah of Torah Vodaath, made a single visit to Eretz Yisrael in his lifetime; in 1971, he spent the summer in Eretz Yisrael, a trip highlighted by the week-long Ponevezh Yarchei Kallah. He later shared his impression of Rav Shmuel.

He related how Rav Shmuel expended an inordinate amount of time and effort preparing his shiurim. He had already mastered the material — that was not what required preparation. His preparation, Rav Pam said, lay in three areas: First, he prepared what to say. Secondly, he prepared what not to say, knowing that some points may delight a rebbi yet confuse a talmid. Finally, there was the presentation of the shiur itself. Of course, the time spent on preparation could have been used to learn another blatt Gemara, to enhance his personal knowledge. “But what does Hashem want?” Rav Pam questioned. “The success of the talmidim, or one’s own blatt Gemara?”

A close talmid who attended to Rav Shmuel related how Rav Shmuel commenced his preparations for the next week’s shiur immediately after returning home from a shiur klali. “The rosh yeshivah has been delivering shiurim for 40 years,” the bochur asked. “Why does he need to prepare so much each time?”

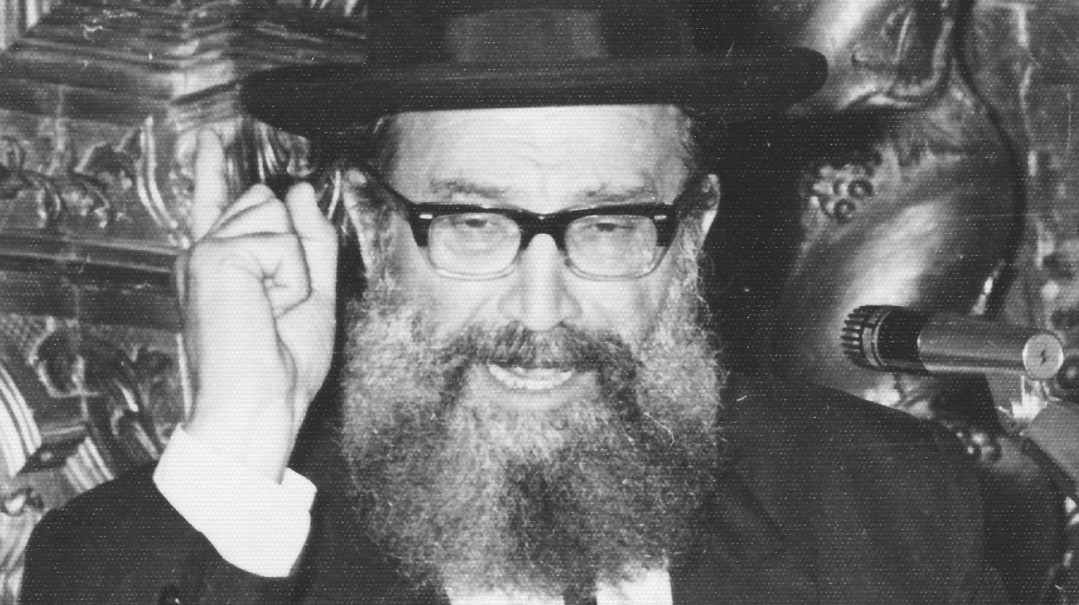

“You’re right,” Rav Shmuel replied. “For 40 years it’s been the same shiurim — although I try to come up with chiddushim each time.” Then he raised his voice and declared loudly, “But the hisragshus (excitement) that I experience each time is as if it’s the first time I’m giving the shiur!”

Nearly 50 years later, the talmid still recalls the intensity of his words.

His shiur was so popular that those who wished to get a prime spot had to literally camp out in the room before the zeman started. As a former talmid related:

“In 1977, the winter zeman opened on Sunday, 30 Tishrei, and Rabbeinu started delivering his daily shiur that very day. As soon as Maariv on Motzaei Shabbos had ended, prior to Havdalah, everyone raced to grab a seat, and we sat there until morning. Someone was kind enough to bring us wine and a candle for Havdalah and, later, food for Melaveh Malkah.”

Rav Shmuel’s shiurim (later published as Chiddushei Rav Shmuel and Shiurei Rav Shmuel) gained much renown during his lifetime and many were published in a variety of “secondhand” sources. Ironically, Rav Shmuel would occasionally state a chiddush of his own, only to discover that his talmidim were already acquainted with it, having heard it from an earlier rebbi of theirs who had repackaged the “chiddush” as his own.

The students’ respect for their rebbi was illustrated in an apocryphal tale popular in yeshivah circles. One Shabbos in the Ponevezh Yeshiva, Rav Dovid Povarsky was absent to attend a family simchah, Rav Shmuel Rozovsky wasn’t feeling well, and Rav Shach was in Yerushalayim. The beis medrash was packed, but when they reached shlishi (the third aliyah, usually given to a prominent scholar), the gabbai declared, “Yaamod… ein kahn shlishi, there is no one here worthy of shlishi.”

He Changed their Hearts

Rav Shmuel successfully instilled an appreciation for Torah in his talmidim as well as their parents, many of whom were initially ambivalent toward full-time Torah study. In fact, when Rav Shmuel first arrived in Petach Tivka, farmers would show up at the Lomza yeshivah during harvest season and naively ask the roshei yeshivah if some bochurim could come out to help them in the fields. The Modzhitzer Rebbe shlita, Rav Chaim Shaul Taub, a talmid of Rav Shmuel, related how Rav Shmuel changed that sentiment:

“With his words, Rav Shmuel inculcated deep love of Torah in the souls of the parents. They exited his house with tears of joy glittering in their eyes, rejoicing at the incredible zechus their sons had to dwell in close proximity to the esteemed rosh yeshivah. His words, which emerged straight from his heart, instigated a fundamental transformation in the parents’ perception and approach toward limud Torah.”

A current gadol b’Yisrael who delivers one of the largest shiurim in the world shared with us a story that he heard firsthand from a relative. The man met a secular Jew in a gas station and upon hearing that his new acquaintance was a student of Rav Shmuel, the fellow grew visibly excited and offered the following story:

“I live in Yerushalayim, and one night I returned home around two or three a.m. As I was making my way down Malachi Street, I passed the Dhurovitch shul and there I heard someone singing the most captivating tune I had ever heard. I felt myself drawn like a magnet to the window of the shul, and there I saw Rav Shmuel sitting and learning Talmud Yerushalmi, I believe maseches Challah, and talking to himself. ‘If it’s like this… then this is the pshat in the Yerushalmi….’

“Since I enjoyed practical jokes, I called out, ‘That’s not the pshat in the Yerushalmi!’ and hurried away. When I glanced behind me, I noticed Rav Shmuel in pursuit. When he caught up with me he asked, ‘Did you say that it’s not the pshat of the Yerushalmi?’

“‘Guilty as charged,’ I admitted. Rav Shmuel took me completely at my word. ‘Why don’t you think so?’

“By now I was starting to feel rather uncomfortable, and I confessed that I had been teasing him, but Rav Shmuel wasn’t satisfied. Putting his arm around me, he said, ‘Even so, you have to tell me what you meant, so come back with me, and we’ll learn the Yerushalmi together, and then you’ll tell me if it’s the right pshat or not.’

“I didn’t feel that I had a choice in the matter, so I retraced my steps together with Rav Shmuel to the beis haknesset, where we sat down to learn. Rav Shmuel explained the topic, and when he finished, he asked me, ‘So, is this the pshat?!’”

Rav Shmuel’s intensity in learning went hand in hand with a heart that throbbed with concern for his fellow Jew. Dr. Efraim Shach, the son of Rav Shach, described the kinship between the two venerable roshei yeshivah: “In 1971, my father underwent a six-hour surgical procedure in Sheba Hospital. Throughout the entire surgery I could see Rav Shmuel through the window, pacing the lawn outside the hospital. When questioned, he said firmly, ‘I refuse to leave until I see Rav Shach after the surgery!’ This episode made such a deep impression on me. He wasn’t family, yet he waited in the hospital for hours until he could be assured that the surgery had been successful.”

The Mashgiach, Rav Yechezkel Levenstein, once asked a bochur, “What is the reason for Reb Shmuel’s success with his talmidim that they flock to him and wish to be close to him?”

The bochur responded, “His incisive, penetrating and unequivocal understanding of what he learns.”

“No!” the Mashgiach responded. “It’s his middos! His ability to build his talmidim in learning! His understanding of a bochur and his sensitivity in encouraging each one’s growth.”

Singing While I Can

Then one day, everything changed. The startling news sent shockwaves throughout the Torah world. Rav Shmuel, the beloved rosh yeshivah, had been diagnosed with late-stage lung cancer at just 62 years old.

When Rav Shmuel first began to feel various pains in late 1977, the doctors thought it was a heart issue, but further testing and X-rays revealed the worst. Upon the recommendations of Israel’s top physicians and with the blessing of Rav Shach, it was decided that Rav Shmuel would travel to America to seek treatment.

The diagnosis and treatment were finalized on a Friday. Mere hours later, at the Shabbos seudah, Rav Shmuel sang the zemiros loudly, exuding enthusiasm. “You’re probably looking at me as if I’m crazy, singing joyously in my situation,” he told a talmid. “Allow me to explain. First of all, it’s Shabbos! Second, in 1948 we were living in Yerushalayim when it was under siege. We were told that the Jordanian legionnaires were about to invade and there might be a massacre.

“I tried feeding my children but they just cried and didn’t want to eat. I could have forced them to eat. But I said to myself, ‘Who knows how long they have to live, why should I force them to eat, let them do what makes them feel best.’ Same thing here: I don’t know how long I will live, so in the meantime I’m singing and praising Hashem.”

That Shabbos afternoon, a talmid observed him at the Chisda Shul, making his way through 40 pages of Gemara with his usual sweetness and intensity.

On Motzaei Shabbos, planning for the trip began in earnest. Rav Shmuel’s entourage — which included his son-in-law Rav Yitzchok Hacker, close talmid Reb Moshe Greineman, and Dr. Moshe Rothschild (others would later join) — would be departing on Monday, and MK Shlomo Lorincz rushed the necessary documents to the US Embassy to ensure visas would be had in time.

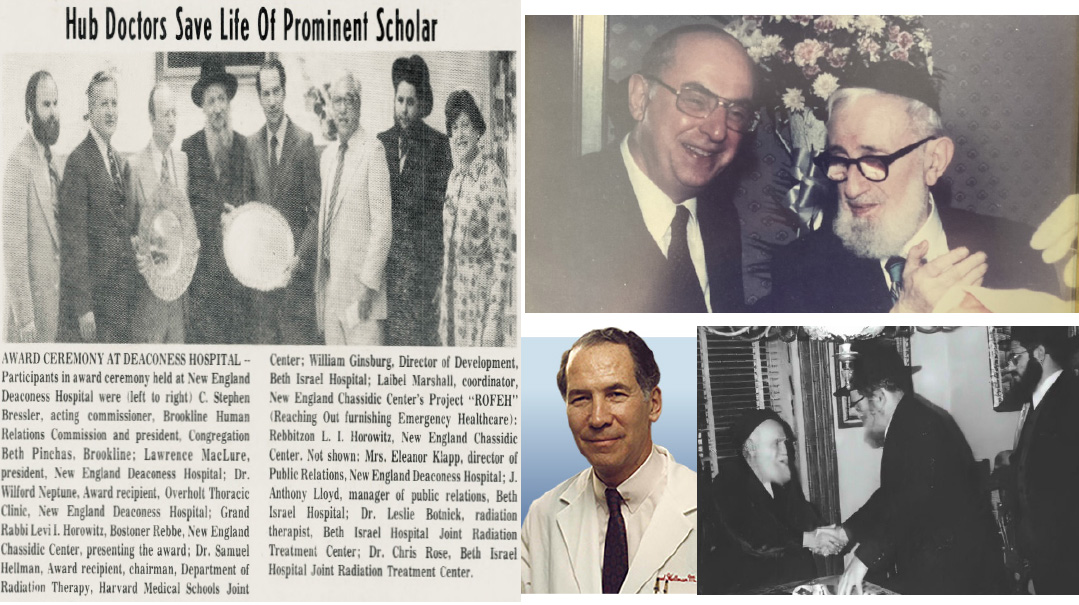

Upon arrival in the US, the group was hosted in Brooklyn by Rav Shmuel’s close friend, Rav Zelig Epstein, rosh yeshivah of Shaar HaTorah-Grodno and a grandson by marriage of Rav Shmuel’s rebbi, Rav Shimon Shkop. After a late-night conference attended by leading askanim and medical authorities, it was decided that Rav Shmuel would seek the guidance of a renowned medical group in Boston, and they immediately contacted Rav Levi Yitzchok Horowitz, the Bostoner Rebbe, whom they knew would be able to assist.

While the Bostoner Rebbe was perhaps best known for his spiritually lifesaving outreach work, another timeless accomplishment was the founding of ROFEH International (Reaching Out Furnishing Emergency Healthcare), an organization dedicated to providing medical referrals and support services to the sick and their families. The Rebbe had no difficulties procuring appointments for Rav Shmuel with the top experts in the field and the rebbe’s son, Rav Meir (the current Bostoner Rebbe of Har Nof) — who had been a talmid of Rav Shmuel in Ponevezh — vacated his home for Rav Shmuel and his group.

Renowned Boston hostess and current Yerushalayim resident Mrs. Avivah Yasnyi was a G-d-send for the vagabond group who did not know a soul in Boston other than the Bostoner Rebbe and his family. Rav Shmuel’s attendant recalled their initial conversation as if it were yesterday:

“The day we arrived we were settling in and the phone started to ring. The woman on the other end introduced herself as Avivah Yasnyi. We didn’t know her, but she would become an important part of the story. Here we were at the end of the world, in America, in Boston, Rav Shmuel is sick and alone. And out of the blue we get this phone call, in American-accented Hebrew: ‘This is Avivah Yasnyi, how can I be of assistance?’ She was like a heaven-sent angel, a savior. She took care of things for us and even accompanied us to the hospital on several occasions, when no member of the Horowitz family was available.”

A Privilege to Treat the Rabbi

Dr. Samuel Hellman, long considered one of the world’s premier radiation oncologists, led the team that would treat Rav Shmuel. Decades later, he still remembers the privilege of treating the premier rosh yeshivah of world Jewry.

“It was the late Bostoner Rebbe who got me involved in this case (and many others),” he said. “He was a great person and when he called, he always had a reason.” Dr. Hellman, a self described secular Jew who grew up in the Bronx, had never heard of Rav Shmuel, but another doctor in the hospital, Dr. Leslie Botnick, quickly filled him in. “I was told that he was a respected figure in Judaism and a great rabbi,” he said. “I was happy to take the case.”

(The Bostoner Rebbe wasn’t the only rabbinic figure to call upon Dr. Hellman for help. He remembers his encounters with Rav Dovid Twersky ztz”l, the Skverrer Rebbe of Boro Park. “The first time Rabbi Twersky called me, he stated his name and said matter-of-factly, ‘Hellman, 44-year-old woman, I need you to see her immediately.’ And of course I saw her. The rabbi called right after the appointment and asked what the prognosis was. I said I couldn’t tell him. Three minutes later, the phone rang. It was a prestigious colleague from Stanford Medical Center who said, ‘Just do what the rabbi says. The family wants him to be updated, eventually you will anyway, and it’ll just make your life easier.’ Five minutes later the Rabbi called for the details. He also told me about yet another case he needed assistance with. Of course I took it on as well.”)

Dr. Hellman and the surgeon, Dr. William Neptune, treated Rav Shmuel with the greatest respect. And the sentiment was mutual — despite the language barrier, they sensed that Rav Shmuel had tremendous appreciation for their work. Dr. Neptune, who was not Jewish, realized he was in the presence of a holy person and refused to take any money for the normally very expensive surgery. “I wish I had the time to come to Israel to hear the Rabbi’s speeches,” he once said.

But even with the surgeon’s fee waived, the costs were still significant. A group of talmidim traveled to Toronto to meet philanthropist Reb Moshe Reichmann and appealed for financial assistance. Reb Moshe listened to their request, but didn’t say much. The next day, he flew to Boston to visit the Ponevezher rosh yeshivah — and paid the entire hospital bill on the way out.

Torah on His Lips

The surgery took place on 11 Adar Beis 1978, and across the world fervent tefillos were recited. As Rav Shmuel floated in and out of consciousness, his lips murmured divrei Torah. Rav Yitzchok Hacker, who sat faithfully at his father-in-law’s bedside, related that while still semi-conscious Rav Shmuel mentioned the Rashbam on Bava Basra in perek Chezkas Habatim, and at one point he shouted, “Gibt ehm a tainah!”

“The entire time we were in Boston he never stopped learning,” another loyal attendant remembers. “We found a Hebrew typewriter in the Horowitz home, which greatly excited Rav Shmuel. He took his notebook, read his notes to me, and I would type. He exhausted every bit of energy on the dissemination of Torah.”

When Rav Shmuel was suffering the agonizing side effects of treatment and could not muster up the strength to open a sefer, he would plead with his attendants and visitors to speak divrei Torah in his presence in order to alleviate his pain, citing the pasuk “Lulei Sorascha shaashu’ai az avad’ti b’onyi — If not for Your Torah my delight, I would surely be lost in my suffering….”

Rav Shmuel had tremendous appreciation for the group that dropped everything to travel with him. When he sensed that one of them desired to “see America” a bit, he joined him on a tour of New York City landmarks, including a tour of the UN, and enjoyed the views from the top of the Empire State Building. While passing Rockefeller Center, Rav Shmuel looked up at the tall buildings blocking the sun and said to his counterpart, “we see here takkeh that this is b’rumo shel olam, the pinnacle of the world.”

What Rav Shmuel lacked in knowledge of the English language, he made up for with wit and humor. One of the Boston residents who regularly attended to him recalls struggling with the new concept of addressing the Rosh Yeshivah in third person, as is customary in yeshivah circles. When she shared her trouble with Rav Shmuel, he nodded and responded in flawless English, “So what are you going to call me, Sammy?”

Despite the grave illness and debilitating radiation treatments that often kept him indoors for long periods of time, Rav Shmuel was determined to dress every day as he did before a shiur klali at Ponevezh. Rav Shmuel had a beautiful hadras panim. Anytime he left his home he’d comb his hair and beard, and inspect his clothing to make sure they were spotless. He would constantly remind those around him how important it was that a ben Torah always reflect the kavod of the Heavenly knowledge he held within. When Rav Avraham Kahaneman came to Boston to visit, Rav Shmuel found out that he was staying in a cheap motel. Rav Shmuel got upset and told him frankly, “You’re a representative of Torah, you must stay in a nicer place.”

To See the Rosh Yeshivah

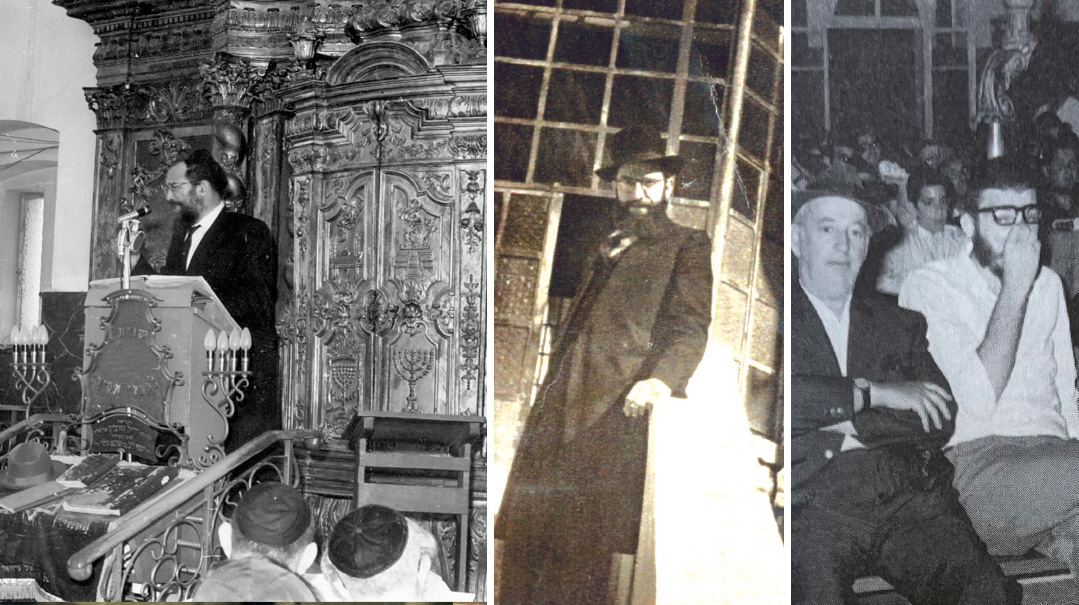

Even in America of the 1970s, where the locals knew little of Ponevezh and its illustrious rosh yeshivah, people would stop in the street and glance at his princely figure, realizing that this was not just another rabbi. And there were numerous requests for visits. Rabbis, roshei yeshivah, Rebbes, businessmen, talmidim, yeshivah students — they all wanted to see the vaunted rosh yeshivah with their own eyes.

Since Rav Shmuel was weak, his gatekeepers had to turn down most of these requests, but people weren’t deterred. Sometimes, Rav Shmuel would exit the house to daven, only to find crowds awaiting him on the sidewalk. Fathers would bring their children to just catch a glimpse of him. When bein hazmanim came along, yeshivah students from across America traveled to Boston to try to see the Ponevezher Rosh Yeshivah.

A young Rabbi Henoch Plotnik was one of the few lucky bochurim to gain entry.

“As a born-and-bred Bostonian, I was home for Pesach bein hazmanim,” he remembers. “I heard that Rav Shmuel was there. I was in Rav Mendel Kaplan’s shiur at the Philadelphia Yeshiva at the time, and I knew that Rav Mendel and Rav Shmuel had learned in Grodno at the same time. I relished the opportunity to meet him. My first attempt was met with a stern ‘no’ from the attendant on duty, but I was told I could return after Yom Tov.”

After Yom Tov, young Henoch went to the Terrace Motel, where Rav Shmuel was then staying, and was told he could stay for ten minutes, as Rav Shmuel was very weak.

“I walked into his room,” he remembers, “and it was so sad to see. Rav Shmuel was as gaunt as the survivors in those photos of the liberation from Dachau, with his once majestic beard reduced to thin hairs. I introduced myself as Rav Mendel’s talmid. He was very pleased and happy, but he told me, ‘Ich hub nisht kein koach’ and I would have to keep my visit short.

“We were having some small talk when suddenly a child walked into the room, walked over to the television set — it was a motel room after all — and turned it on. I do not remember what came on the screen, if anything at all. But I do remember that it was as if the room was on fire! Rav Shmuel jumped out of his bed and screamed as loud as he could to shut the TV. No doubt his holy eyes would not tolerate what could potentially be appearing on that screen. This poor child, who probably didn’t even know what he was doing, was gone like the speed of light after turning off the knob. With the spiritual danger averted, Rav Shmuel laid back in bed and gently asked me if I could end my visit, ‘Vayil ich hub nisht kein koach.’

“It was an unbelievable sight,” Rabbi Plotnik says. “He was a dying man utterly bereft of strength, yet when a threat to his kedushah v’taharah presented itself, he was a gibbor k’ari and mustered the energy to do what he felt needed to be done. Before I left, he begged me for a brachah. I asked him whatever for, I am just some teenage bochur and he is who he is. He would not relent and stated quite firmly that he needs brachos, so I did my part and gave a birchas hedyot. And of course I asked him for a brachah as well: that I should merit learning in Ponevezh one day, hopefully in his shiur. Half of his brachah came true a few years later; sadly, I wasn’t zocheh to the second part.”

Another Boston Jew who extended himself for Rav Shmuel was Reb Shraga Feivel (Phillip) Cohen. Reb Feivel was a renowned mokir rabbanan who would routinely drop all of his affairs in order to attend to the numerous rabbanim who came to Boston for medical treatments.

One day in the midst of a snowstorm, Reb Feivel arrived at Rav Shmuel’s lodgings with a special guest: Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik. Rav Yoshe Ber wished to meet the great Rosh Yeshivah about whom he’d heard so much.

Rav Soloveitchik removed his coat, Rav Shmuel greeted him with “Vos macht ir?” to which Rav Soloveitchik quickly replied, “Vos macht ir?” They then sat for an hour or two and spoke in learning. The two roshei yeshivah became animated at times, raising their voices and waving their arms.

These meetings repeated themselves several times, with Rav Shmuel returning the favor and visiting Rav Soloveitchik as well. Rav Shmuel was very impressed by Rav Soloveitchik, and Rav Soloveitchik in turn saw true greatness in Rav Shmuel, saying to Reb Feivel, “The world says that he’s a talmid of Rav Shimon (Shkop), but I saw the clear influence of my uncle, the Brisker Rav.”

During the respites between treatments, Rav Shmuel stayed in Boro Park with his relatives, the Blumenfeld family. During those periods, Rav Shmuel visited an elderly Rav Moshe Feinstein, who made a point of walking the esteemed guest out.

Literal mobs of people would follow Rav Shmuel and his every move, and he begged his hosts to find him somewhere to learn in solitude. Once, he discovered a chassidic shtibel in Williamsburg where he could study incognito, and relished every moment of his anonymity.

Orphaned Generation

On May 21st Rav Shmuel returned home, where a large reception greeted him at the airport. The joy in the air was palpable. One talmid — today a world renowned marbitz Torah — even jumped onto the hood of the car and began to shout “Rabbeinu! Rabbeinu!”, and masses of talmidim paraded him back home, singing and dancing through the streets of Bnei Brak.

But the joy was short-lived. Early in 1979 the cancer returned with a vengeance. Rav Shmuel returned to the United States once again — this time with the knowledge that any respite from the ferocious disease was a long shot.

Rav Shmuel and his wife Esther (nee Frank) had been divorced many years earlier. Rav Shmuel would later marry an ishah chashuvah, Mrs. Chana Esther Friedman, who passed away in 1972. The beginning of his second US trip marked a sweet but somber occasion. At a small ceremony held at the Boston home of Reb Feivel Cohen, Rav Shmuel remarried his first wife. Keenly aware that Rav Shmuel was suffering greatly, and his days were perhaps numbered, she relished the opportunity to care for him and made an effort to make his final months as comfortable as possible. Rav Zelig Epstein came from New York to be the mesader kiddushin, and the baalas habayis, Mrs. Ruth Cohen, prepared the small seudah that followed.

Rav Shmuel and his rebbetzin made their home at a small hotel in the area. Reb Feivel Cohen decided to spruce up their accommodations, personally dragging in a recliner chair that might make the Rosh Yeshivah a bit more comfortable. But watching the Rosh Yeshivah suffer was more than the normally stoic man could handle, and Reb Feivel would regularly break down in tears.

The doctors in Boston did their best, but their efforts yielded few fruits. In the summer of 1979 Rav Shmuel and his entourage again returned to Eretz Yisrael where Rav Shmuel spent his final months. During the final days of his life, when sustaining terrible physical pain, he called out for his rebbi Rav Shimon Shkop, crying, “Rav Shimon! Please be a meilitz yosher for me!”

On Motzaei Shabbos, the 27th day of Tammuz, Rav Shmuel returned his holy soul to his Maker. In an interview with Rav Shmuel’s daughter Rebbetzin Sarah Rotberg, Rav Yisroel Gustman articulated the searing loss he felt at the passing of this Torah giant he’d learned with back at the beginning of the journey, when Rav Shmuel was a gifted young boy:

“When Rav Shmuel was niftar, I couldn’t sleep all through the seven days of shivah. I lay in bed, but I couldn’t fall asleep. Rav Shmuel! Rav Shmuel! He left us when he was so young! Now our generation is orphaned…. His honesty! His erlichkeit! And his love for his talmidim! He so loved his talmidim; they were like his children…. Thousands of talmidim…. The Ribbono shel Olam knew exactly what He was doing. But it is so heartbreaking, so painful.”

Rav Gustman’s poignant words expressed the feelings of Klal Yisrael. Rav Shmuel’s passing orphaned the entire yeshivah world — because he was everyone’s rebbi. He left his mark on countless minds and charted a path that’s still being followed.

An American rav who attended Ponevezh in the 1980s related how Rav Shmuel’s popularity ceased to diminish following his untimely death. He recalled how the students would play cassettes of Rav Shmuel’s shiurim each Sunday night in a shiur room. He walked in one night and witnessed a most peculiar sight. The tape recorder was on a chair, in the middle of a circle of other chairs, all with tape recorders on them. There was not one human being in the room!

Even today, decades later, the shiurim are still playing and his teachings still resonate. There is hardly a ben Torah in our generation who hasn’t been touched by Rav Shmuel’s derech halimud. His Torah became a permanent asset of the Torah world. In batei medrash across the globe, generations of talmidim who never saw his shining face still murmur his words, thrill at his insights, and are guided on their journey through Gemara by the genius from Grodno who helped build not just a single yeshivah on a Bnei Brak hill, but the entire resurgence of the yeshivah world.

Information for this article was culled from more than a dozen oral interviews as well as numerous secondary sources, notedly the (highly recommended) biography of Rav Shmuel entitled The Rosh Yeshiva by Rav Menachem Chaim Rozovksy (Israel Book Shop) and the newly released biography of the Bostoner Rebbe The Rabbi on Beacon Street by Rabbi Shimon Finkelman (ArtScroll/ Mesorah Publications). Special thanks to Rabbi Zev Cohen, Rabbi Henoch Plotnik, Rabbi Shimon Meller, Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Rabbi Mordechai Kamenetsky, Reb Cheskel Privalsky, Reb Moshe Greineman, Dr. Samuel Hellman, Sruli Besser, Reb Abish Brodt, and Mrs. Avivah Yasnyi for their assistance.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 860)

Oops! We could not locate your form.