Lock and Key

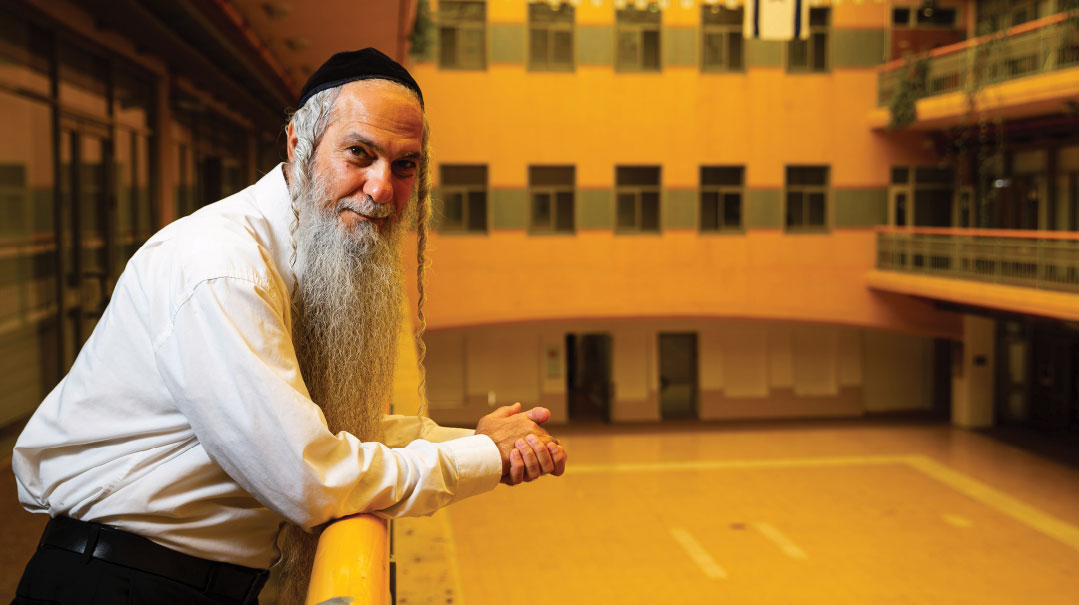

| December 2, 2020In the eyes of the world, Rabbi Cohen’s men have reached their rock bottom, but in the eyes of those inmates, he’s an angel sent from Above to confirm their indelible humanity

Between jutting boulders and slabs of rock on an isolated strip of beach along the Jaffa coast, Rabbi Avinoam Cohen sits in a circle with a motley group of men, from their twenties to their fifties. In the center, he places a pile of stones.

“Now we’re going to do our version of Tashlich,” he tells the men as he hands out pieces of paper and pens.

While grown men generally have better things to do than play a social-interaction game on the beach, for these fellows the exercise can be life-altering. They are prisoners on their way back to real life, and Rabbi Cohen, developer and director of the religious section of Israel’s Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority, is their light at the end of a dark tunnel — the last hope of many who want to find their way back to normative society outside prison walls.

How does he transform a person who’s spent years in prison and reconstitute him as a “regular” citizen? Tough emotional work, says Rabbi Cohen, is part of the process for these men who’ve committed to embark on their personal teshuvah process, and this exercise is one example.

“Each one of the men shares with the group the crime he was jailed for, and is asked to look into himself and home in on the trait that caused him to commit the crime, and to write it down on the paper,” Rabbi Cohen explains. “For example, if a person sold hard drugs and experienced a subsequent descent to the underworld, perhaps the motivating middah is atzlanut, laziness — he wanted quick cash and didn’t have the self-discipline or energy to get out there and work. Instead he tried to make easy money, which devolved into crimes and serious moral issues. So the prisoner writes ‘laziness’ on a piece of paper, chooses a stone from the pile, wraps the paper around the stone, and when everyone is done, we do a symbolic ‘tashlich’ — each one tosses his stone into the sea.”

Of course, throwing a rock is not a substitute for the real work of transformation. But this exercise is part of a bigger program — a process that calls for introspection, incremental change, and enduring commitment. And when the prisoners follow the process to its end, they succeed in rebuilding their very identities.

Lost and Found

From a small room inside the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority in Jerusalem’s Givat Shaul neighborhood, Rabbi Avinoam Cohen manages programs that have changed the lives of hundreds of people. In the eyes of the world, these people have reached as low as one can go — they were imprisoned following convictions for severe crimes. But in the eyes of the prisoners, Rabbi Cohen is an angel sent from Above to confirm their indelible humanity and to help extricate them from their current straits.

“For every sin there is teshuvah, and it makes no difference what the sin is,” Rabbi Cohen emphasizes. “The mechanism of repair is different for every sin, but the principle guiding us is that there is no transgression in the world that can’t be atoned or repented for, as long as there is sincere repentance and remorse. This isn’t my original idea. Hashem said it — it’s written in the Torah.”

The walls of his office are like a gallery of rebbe cards: There’s the main picture over his desk, of his personal rebbe and Breslov mashpia, Rav Shalom Arush, whose messages of faith, love, and gratitude he says prisoners overwhelmingly connect to. There’s also the Baba Sali, the Ben Ish Chai, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Steipler, and several others — because, as Rabbi Cohen says, each of these gedolim represents a pathway, another tool in the toolbox. “My job here isn’t to do the rehabilitating,” he explains. “My job is to provide Torah-based tools to the people who decide they want a better, meaningful life. I can’t do the work for you, but I can offer you the toolbox.”

Rabbi Cohen has been at the head of the religious rehab division for over two decades. Before that, he spent a similar amount of time doing a very different job — or was it?

“I ran the lost-and-found department at Israel’s Postal Authority,” he says, comparing his previous position to his current one, with the perspective of 20 years. “There are lots of similarities,” he says. “At the Israel Post, I was in charge of returning lost items, and today I’m also responsible for returning lost items. Each of these men is spiritually lost, and it’s a process to restore the lost item to its Owner.”

Rabbi Cohen, who himself became a chozer b’teshuvah more than 30 years ago, got involved in prisoner rehabilitation while still in his other job. “I volunteered for an organization that dealt with prisoners, and I felt that there was a lot that could be improved, instead of just locking people up and throwing away the key, burying the person’s neshamah along with his sins.”

When he was offered the position at the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority, he grabbed the chance, driven by a desire to see better results. But he admits that at the beginning, his success was limited.

“While I saw the treatment as a purely spiritual engagement, the regulations obligated us to use conventional therapies as well. I didn’t like that, because I felt the spiritual component was such a huge piece in the rehab puzzle. But the truth is that once I stepped back a bit and connected to the standard therapies, I was then able to incorporate the religious and spiritual components of the therapy process. And the resulting model worked well.”

Hard Work

Not all prisoners are eligible for rehabilitation. Prison chaplains must recommend a prisoner as a good candidate for rehab in the last third of his prison sentence, or if the parole board agrees to reduce the incarceration due to good behavior. Then Rabbi Cohen and his staff are responsible for coordinating a personalized program for each prisoner, which can include stays in halfway houses and, depending on the nature of the crime, ongoing therapy.

Over the years, the requests have increased, and today, demand for Rabbi Cohen’s programs is greater than the availability. When he started out, he had around 15 inmates in the religious rehab program; today there are around 200 at any given time. In the early days, Rabbi Cohen worked alone, traveling around the country to the various prisons and designing rudimentary programs on a shoestring budget. Today, as his program has proven itself, there’s a staff and a system in place. In fact, a tefillah he composed for himself has become an official prayer for the entire rehab authority. It’s even hanging on the walls of various departments.

“It’s a tefillah I say every day, asking for siyata d’Shmaya to reach the hearts of these prisoners. I ask for chochmah, binah, and daat in being able to reach them, without a speck of haughtiness or ego. I tell Hashem, ‘I know You’ve sent me here to fix and not to break, so I ask You to send me the right tools for their spiritual healing.’”

Rabbi Cohen warns the enrollees in his program that they’ll have to work hard. This process is not about sitting around with guitars at a kumzitz and feeling spiritual. It’s about digging deep into the nefesh, flushing out the core mistaken beliefs — the self-pity and the hopelessness — and filling that place instead with belief in one’s own worthiness, the ability to change and do teshuvah, and belovedness in Hashem’s eyes no matter how far he’s fallen.

“If you’re here, you have to be committed to working hard,” he says. “Many of these men never believed they could actually achieve something positive with hard work. Most of the people I deal with have suffered from attention deficit disorders from childhood, a problem that was never properly addressed and basically insured their failure in the mainstream world. Many looked for an easier way, driven by the desire for fast money, a fancy car, designer clothes, and the like. But what I’ve discovered is that when all that distraction is taken away and physical freedom is limited to a two-by-two cell — with no phone, no independence, no expression of self — then the spiritual freedom finally has a chance to develop.”

Numbers Don’t Lie

What keeps Rabbi Cohen forging ahead is the fundamental knowledge that no one is born a sinner. “Everyone is born free from sin,” he says, “but during the course of life, he goes through all kinds of challenges that his soul is designated to endure. The only question is how he reacts to these challenges. Will he choose life, or will his choice be a life of crime and despair?”

It’s hard to throw Rabbi Cohen off his game: As a chozer b’teshuvah for several decades, he knows what it means to turn one’s life around, to find forgiveness from oneself, and to reach a better spiritual place despite the past. He’s designed what he calls the “Three Step Program,” but clarifies that “the Rambam gets the credit.” It’s based on the Rambam’s three steps to teshuvah, which even the lowliest sinner can attain if he’s really ready to make the switch.

Vidui (confession/admission), charatah (remorse), and kabbalah al ha’asid (a decision to change) are the basis for atonement. “We added our own work to this outline,” Rabbi Cohen explains, and for him, the key is empathy. “It’s the only way I can succeed in understanding the person in front of me, and figuring out how he made the decision to commit the crime. I don’t denounce them. Instead, I try to go back with them to the misguided concepts and priorities they encountered and picked up. A person isn’t born a criminal. There was some kind of evolution over the years. So we go back to those points that turned him into a criminal and we try to correct the thinking.”

He says that his own baal teshuvah background has been an asset. “The koach of a baal teshuvah is huge,” says Rabbi Cohen, “and I use what I know from my own past, tapping into my own journey, so that I can see the Torah from their perspective. But there’s another thing too — once I started this, my own Torah learning also changed. I learned that the secrets of shikum, of rehabilitation, are actually found in the Torah itself.”

It’s hard to argue with the numbers. A few years ago, Rabbi Cohen got the backing for his vision through a study that completely transformed the thinking about prisoner rehabilitation. The study, managed by a team of researchers at the Rupin Academic Center, determined that only 14.3% of participants in the Torani rehabilitation programs suffer recidivism, while 34.1 percent of those in the general rehab programs revert to the world of crime.

Spiritual Anchor

The gates of the Hadarim prison in central Israel look ominous this morning, but that doesn’t stop Rabbi Cohen from walking through the main entrance, presenting his pass and entering the heavily-guarded complex. His first stop is the office of the prisoner chaplain, where he receives a list of prisoners who’ve submitted a request to join Rabbi Cohen’s rehabilitation program.

“I call each prisoner for a personal meeting,” he explains. Because the division’s budget and manpower are limited, not all prisoners will be accepted. “I ask him lots of questions, trying to ascertain if he’s serious about change and suitable for the program. Is he really looking to change, or does he just want to cut the process short and get his sentence reduced?”

After meeting the prisoner, Rabbi Cohen then has another meeting — this time with the prison therapists. “I get their opinion, read the files and the reports, and look for points in their favor. I don’t want to hear about the man’s past, I just want to hear a professional opinion about his emotional state: Where is he up to today, how does he respond to circumstances? It doesn’t interest me at this point why he got into prison. In the journey toward teshuvah and growth, it doesn’t really make a difference which crime the person committed.”

At this point, Rabbi Cohen prepares a summary and then meets with the prison chaplain yet again. “I tell him to give me his opinion of each prisoner who has been interviewed, since he knows them and has ongoing contact with them. That helps me make the final decision. And then comes the hard part — tailoring a program to the inmates’ individual circumstances for maximum success.”

Along with traditional therapies and interventions, the rehab program includes some kind of employment and a connection with a Torah group, such as a kollel or yeshivah. “I choose the kollel based on my acquaintance with the rosh kollel,” Rabbi Cohen explains. “For example, if someone committed fraud, I’ll ask that someone should learn the halachos of fraud with him. And he’s usually open to it, because spirituality has gained a greater significance for him during his incarceration.”

Ultimately, says Rabbi Cohen, the religious factor is the most important in the homecoming process. “The same One Who gives the ability to sin, gives the ability to repent and rectify. So even though the tailor-made Torah aspect of the program is sometimes more complicated for us to ensure a good fit, it’s also the most powerful piece. Torah tools are what keep the recidivism rate so low.”

The learning also serves as an anchor, even — and especially — once the prisoner has been released. “A person can be released from prison, but may not have released the prison from himself,” Rabbi Cohen says. “It take a long time for ex-prisoners to become ‘regular’ people. Some tell me that they start sweating every time they hear a police siren. Integrating into a Torah framework makes it easier for them to become part of society around them.”

One day, a former prisoner invited Rabbi Cohen to his home in a small moshav. “When I arrived, he wanted to show me something in the barn. At the entrance was a large, threatening dog, the type that you want to run away from. When the dog saw us approaching, he began to leap wildly and bark and bite the bars of the cage he was in. Then the man told me something remarkable: ‘That’s how I once was. That dog used to leap around in my soul. Today, I remember it and say, Is that what I want to be like? And then I restrain myself….’ ”

Kippah in Court

Why do Jewish inmates in Israeli prisons embrace religion? What initially motivates them to participate in a minyan or a shiur during their incarceration and what are their motivations to make a deeper commitment to halachah? Is it just because the religious wings in Israeli prisons are considered preferable, or are there in fact intrinsic benefits that lead them to continue a Torah lifestyle after they’re released?

“I know all about the ‘kippah in court’ phenomenon — where an irreligious prisoner shows up to a hearing wearing a head-covering, to show how religious he’s become,” Rabbi Cohen says. “But in contrast to those who claim it’s insincere, I live the field and see the prisoner not only through the media cameras at the court entrance. I accompany him for many months in an official capacity, and for years afterward as an informal support. Sure, we all make fun of the prisoner who suddenly shows up in court with a big white yarmulke, but it’s much deeper than that. There’s a process here that might begin with that white yarmulke, but it often ends with a new life as a ben Torah.

“Because really,” Rabbi Cohen continues, “what is the definition of a religious person? Once, I thought ‘religious’ meant putting on tefillin and keeping Shabbos. Today I know it’s different. True, everyone knows that putting on a kippah before a judge might not be the most effective tactic, but that small, symbolic move really is meaningful. Because in the place where these prisoners are, the material part of their life has been stripped down and now plays a very minor role. They have no freedom, they have little by way of material comforts, and that’s when spirituality thrives. A person who has lived a very materialistic life suddenly lands up in a small room that he has to share with six people. So he picks up a Tehillim for the first time in his life. What happened? He realizes that he has nothing, and he can’t do anything about it. But there is one thing that can’t be imprisoned — a person’s spirit.”

One day, Rabbi Cohen received a call from a man who had committed a serious crime 17 years earlier. “He’d gone through the program and came out of prison as a sincere baal teshuvah, following all the protocols for follow-up and therapy, and he wanted to make a final restitution by contacting the family of his victim to ask them for forgiveness. In conversation with the family, we reached the conclusion that it wasn’t a good idea for him to meet them — it was just too hard for them to look him in the face, knowing what he’d done. But when they heard that he’d become sincerely Torah-observant and remorseful, they said it made it easier for them to move toward mechilah.”

In the Merit of Shabbos One case that helped solidify Rabbi Cohen’s belief in his approach to rehabilitation was a prisoner with practically zero Jewish knowledge who’d been convicted of serious crimes. Although he led a totally secular life, the prison rabbi somehow sensed he’d be a good candidate and allowed him to join the religious rehab program.

“This fellow, I’ll call him Yehuda, knew nothing about Shabbat,” Rabbi Cohen relates, “and was surprised to see that the table was set as nicely as possible with the limited resources available to the prisoners. Believe me, they do a great job with the bit that they have. Before davening, Yehuda sat down, ready to eat. They told him, ‘Yehuda, wait. We need to pray.’ They gave him a siddur, he followed along, and then sat down to eat. Again they told him, ‘Yehuda, wait. We need to make Kiddush.’ After Kiddush, he stuck his hand out to take challah, and then one of the prisoners stopped him and told him he needs to wash. Then they stopped him again because he had to make a brachah together with them. And that’s what he did. At the end of the meal, they showed him how to recite Bircat Hamazon.

“Today, Yehuda is Torah observant. He once shared with me that that Shabbat was the first time he ever remembers delaying gratification. Until then, he did whatever he wanted, totally unrestrained. It never even dawned on him that not everything a person desires is permissible, and his immediate right.

“You know, among the therapists there is a big debate: Does Shabbat observance play a role in rehabilitation? I once had a discussion with an irreligious social worker who insisted that Shabbat had no therapeutic value. I shared Yehuda’s story, explaining that during the week, we generally don’t think about the mundane activities we do every day, but on Shabbat, even tearing toilet paper is an act that requires preparation and thought. Whether or not you can turn on the air conditioner or the lights or talk on the phone or text — for us, it’s routine, but there are people who, when confronted for the first time with having to think before every daily instinctive action, it simply changes their life.”

Rabbi Cohen explains that impulse control, thinking before action, is the most life-altering behavior for a person who’s lived a life of crime and transgression. So much so, that in his department, these men actually receive a certificate of merit for every positive action, sort of like a good-behavior star chart.

“And you should see the smiles on their faces when they get their awards. For many of them, it’s the first time in their life they’re getting a certificate, the first time they’ve actually taken something positive in their life to the end — and succeeded. And when they feel good inside, we know we’ve contributed our part in motivating them to make something of their lives, to help them become men of character and control.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 838)

Oops! We could not locate your form.