An Ocean of Love

A brilliant light in a most imperfect vessel. The vessel became ever frailer, but his yeshivah grew only stronger

Jerusalem's Rechov Ha'amelim is not a residential street. The buildings house metal-workers, with scenes of orange sparks flying off blowtorches, and wood-workers, their sawdust blowing out with the gentlest breeze. There is a bakery, its massive oven piping hot well before the sun rises, and a silver-restoration workshop, where precision and concentration are necessary all day, every day.

It's a street where toil is in the air, where effort and exertion crisscross the bumpy road like winter's puddles. A street of Amelim, literally “toilers.”

There is but one residence on the street, and in terms of sheer hard work, it towers above the line of shops at its side. The home of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, Rosh Yeshivas Mir.

They labor and he labored....

They labor and receive their recompense: crumpled bills. He labored and found life, joy, an ecstasy so profound it defined him -- and impacted thousands of people who saw themselves as his talmidim.

“Eidus hi l'baei olam, it is a testimony for mankind, shehaShechina shoreh b'Yisroel, that the Divine Presence dwells with Yisroel.

“Mai eidus? What, precisely, constitutes this testimony?

“Zo ner ma'aravi: the western lamp of the Menorah received no more oil that the other lamps, yet the other lamps were all kindled from its light, and it remained burning after the others had burnt out.”

- Shabbos 22b

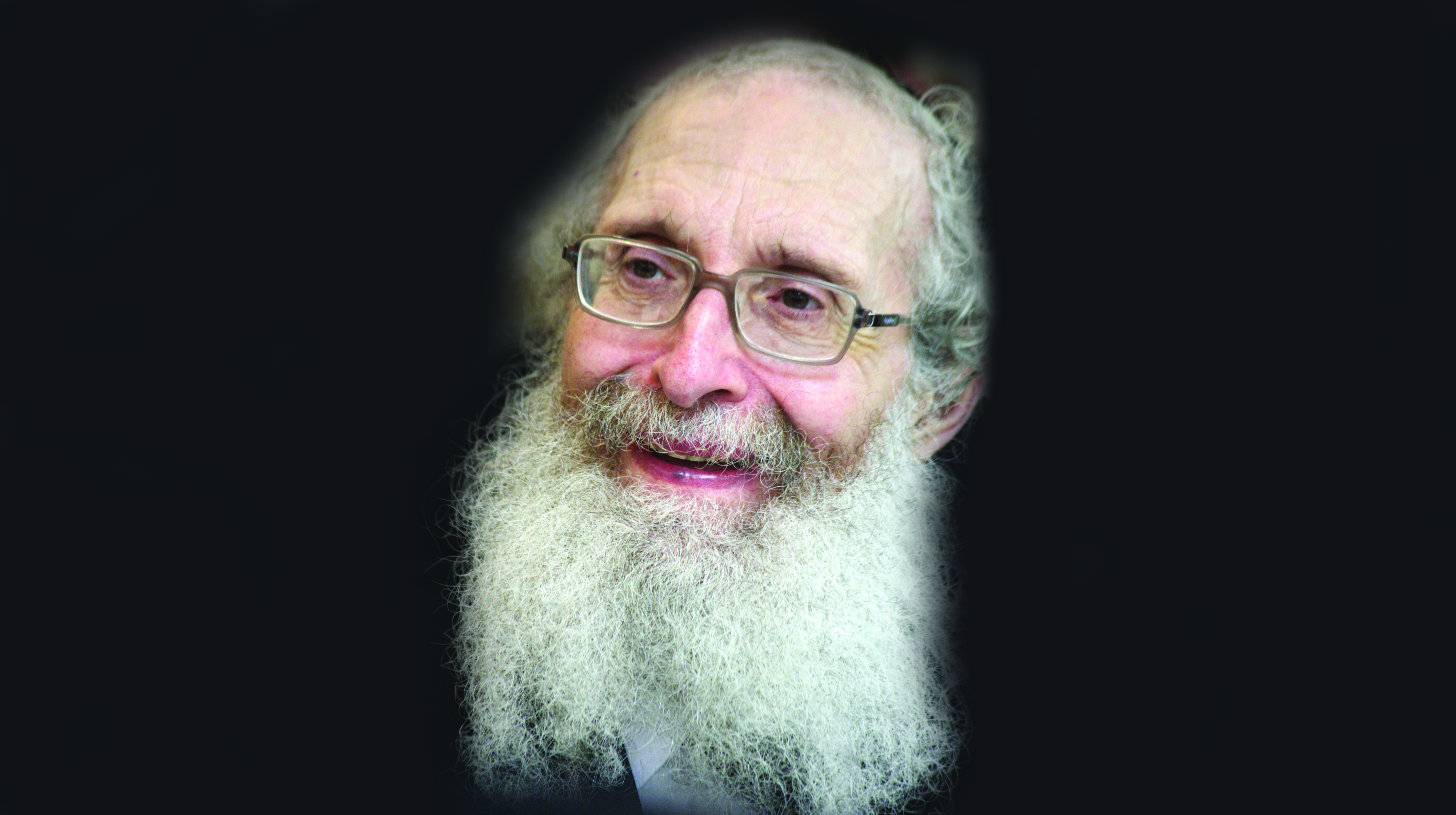

“We must thank Hashem for the gifts he’s given us.” Rav Nosson Tzvi rejoicing with the most precious gift of all

Until just a week ago, there lived a man whose being testified to the words of the mishna - The Torah gives him kingship.

He proved that the Torah cloaks those who learn it with majesty, grace and dignity. That a figure rendered helpless by physical limitations could exude strength and focus, power and limitless ability.

The face of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Mirrer rosh yeshiva, was testimony that the Shechina rests among Yisroel.

Like the western lamp of ancient times, the greatest modern-day citadel of Torah , the Mirrer Yeshivah of Jerusalem, had a ner-tamid, a perpetual, constant light. Consistent: seder after seder, blatt after blatt, chavrusos overlapping with their replacements. And the light? His smile could illuminate the darkest room, awaken the most dormant soul.

I never saw eyes that could dance as his, or a countenance so suffused - despite unmistakable lines of exertion and travail - with nobility.

Now the ner tamid, the brilliant light in a most imperfect vessel, has been snuffed out.

A Shmuess and a Song

One of the highlights of the week during my own time at the Mirrer Yeshivah was Rav Nosson Tzvi’ss Friday shmuess, delivered in his dining room. Since he spoke in English, the crowd was somewhat different from the standard audience. Rav Nosson Tzvi seemed different too; he was more relaxed and he spoke with a certain freedom and candor.

There would be a sefer open on the table when we filed in - more often than not, Chofetz Chaim al haTorah - and he would share an insight or thought, using it as a springboard to

“We must thank Hashem for the gifts he’s given us.” Rav Nosson Tzvi rejoicing with the most precious gift of all

other topics, often anecdotes and incidents from the preceding week.

But always, he would return to the same theme. The same word, really.

Torah.

We could hear the love in his voice

No composer, no poet, has ever invested a word with more feeling than he infused into that word. “Tey-reh,” he would say, his voice lyrical, an ode of yearning and love.

His heart was a like a guitar, each string sensitive and awake to hisorerus, and on those Fridays, he’d share the inspiration with us.

During the week marking the yahrzeit of his revered father-in-law Rav Beinish Finkel, he described how Reb Beinish succeeded in keeping all his holy fire inside of him, showing nothing to the world. Rav Nosson Tzvi used the words of a zemer that his father-in-law would sing on leil Shabbos, “libi uvsari yeranenu l'Kel chai,” to express the avodah of Reb Beinish, whose innards sang.

Then the rosh yeshiva stopped, mid-shmuess, and began to sing the words “Libi uvsari, libi, libi uvsari,” to a niggun composed by Rav Meir Shapiro. Instantly, everyone began to sing along, and for several minutes, we tasted - if only temporarily - what it means: Libi uvsari yeranenu...

During those weeks that he'd met with gedolim, come Friday he would allow us a glimpse of his impressions. This week I met Rav Shmuel Wosner, he told us, and he spent the shmuess describing the incredible yishuv hadaas he'd seen, the way the Shevet Halevi measures each and every word before he speaks, the tranquility that envelops him.

He told us of observing Rav Elyashiv before an appointment, and illustrated the simple, almost child-like way the gadol hador learned the gemara, chanting “Amar Abaya...what does Rava answer? You hear Abaye? What do you say to that? And you, Rava, how will you respond to Abaye's claim?”

One week, he described how as a yungerman, he was walking along with Reb Chaim Shmuelevitz, engrossed in learning. They walked up the road across from the Mirrer Yeshiva, passing by a strip of stores, and Reb Chaim suddenly stopped in front of one of them. It was a shoe store, and in the doorway was a large basket filled with little children’s footwear, a mountain of tiny shoes. Reb Chaim was silent for one minute, two minutes, and then a tear fell from his eye.

Rav Nosson Tzvi was bewildered. Reb Chaim explained. “I saw the pile of little shoes, shoes that will be purchased by mothers for their own toddlers, most likely the first pair. I started to think about the feelings of a mother buying that first pair of shoes for her child and the joy that will fill her tender heart as she prepares to equip him for the path ahead. Contemplating her joy, I feel it too, and therefore I cry.”

That was the shmuess. That day, we cried along.

And sometimes, he would tell us about his youth, about the teenager who came from Chicago to visit his great-uncle, the Mirrer rosh yeshiva, Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel.

He would often describe how he slept in Reb Leizer Yudel's own home, in a curtained-off section of the living room. Reb Leizer Yudel would arise early, four o'clock in the morning, and learn eight blatt before shacharis, knowing that he’d be consumed with yeshiva duties all day. The nephew from Chicago would often feign sleep and watch his uncle's entry to the room.

“He would tiptoe in so as not to wake me, still in his shirt-sleeves,” Rav Nosson Tzvi recreated the scene years later. “He wore a wide smile, and as he approached the sefarim shelf, he spread his arms apart. He leaned over and embraced the sefarim, kissing lone volumes, saying the names to himself, like a mother saying 'good morning' to her children.”

Then Rav Nosson Tzvi stopped, his own face pained with nostalgia, and listed off the names, saying each one slowly. “Teshuvos HaRosh, Ri Migash, Rav Akiva Eiger, Afikei Yam...” We, his listeners, wanted nothing more than to run and master those sefarim, so melodious was his voice.

Rav Nosson Tzvi would tell about his first winter zman in yeshiva, after Rav Leizer Yudel had convinced his parents to allow him to remain in Jerusalem for a few months. “The rosh yeshiva arranged six chavrusos for me, three groups of two, with each two teaching me a different twenty blatt in Mesechta Bava Kamma. They chazzered it with me three times each, so that I reviewed it six times with chavrusos. Then, I reviewed those same sixty blatt seven more times on my own, for a total of thirteen times. After that, I felt like I'd entered Bava Kamma.”

The rosh yeshiva would smile. “You know what? Bava Kamma is still so special to me...”

There was something he didn't tell us. Rav Leizer Yudel had approached the most prestigious yungerman in the yeshiva, Rav Chaim Kamil, and said, “I am trusting you with developing a diamond. Don't let me down.”

Ultimately, Rav Chaim Kamil would become rosh yeshiva in Ofakim, in the Negev, but he remained the rebbi muvhak of Rav Nosson Tzvi until his own passing, just a few years ago.

And one last story from the Friday shmuess. The rosh yeshiva had married off a son that week, in Bnei Brak. Of course, we'd all gone to the wedding - not out of a sense of duty, but with the excitement reserved for family and close friends. The chasunah was something special, an outpouring of love and reverence for a rosh yeshiva of thousands, from thousands.

“I want to share something with you, gentlemen,” the rosh yeshiva began the Friday shmuess that week. “After the chasuna this week, my new mechutan said to me, 'I never saw a relationship like the one you have with the Mirrer bochurim; zeh kmo okyanus shel ahava, it's an ocean of love.”

Rav Nosson Tzvi looked around the room, his eyes shining as he focused on each and every person. Then he continued. “I just wanted to say thank you.”

Masses of bereft Jews, still reeling from shock, at the levayah last Tuesday

My Talmid

It's a unique feature of the relationship the rosh yeshiva had with his talmidim: there was no elite subset of bochurim that were “his type.” Each of them, the more yeshivish and less so, the intellectually gifted and the more emotional ones, the cynical and the sincere and the back-off types, they all felt close to the American-born descendant of the Alter of Slabodka, who had journeyed to the small Mirrer Yeshivah in Jerusalem and found himself at its helm. Yerushalmim and Israelis and Americans and Europeans and South-Africans all had “their” special connection with the rosh yeshiva.

Sure, they would observe him - the illness, the exhaustive schedule of shiurim, the personal chavrusos that piled up against each other, the crushing budget, the bureaucracy of running the world's biggest yeshiva - and wonder, “Does he really know me?”

And always, he answered the question.

He had private weekly chaburos with the alumni of the many yeshivos that were represented in the Mir, and one talmid, whose chaburah met each Wednesday, had the job of approaching the rosh yeshiva on Wednesday morning and confirming if the chaburah would be running on schedule.

Years later, that bochur was learning in Lakewood, and the rosh yeshiva came for a visit. At the massive kabbalas panim, the bochur waited on line with hundreds of others, wondering if there was any point. The rosh yeshiva looked wan, tired from his trip, and the line seemed endless.

His turn finally came, and the rosh yeshiva grasped his hand, his voice a whisper. “We miss you on Wednesday,” Rav Nosson Tzvi said.

Chaim, a talmid, traveled to New York from an out-of-town community for the yeshiva's annual dinner, simply to say 'Shalom aleichem' and greet his rosh yeshiva. He too studied the line ahead of him and was consumed by doubt. The rosh yeshiva doesn't even know who I am, he though. He has six thousand new talmidim in yeshiva and it's been a while since I left. I wasn't even that close to him when I was there.

The thoughts plagued him, and he considered leaving.

“But I've come all this way, what can I lose?” he asked himself before the questions returned again.

He waited it out, and his turn came.

The rosh yeshiva extended his hand, reaching for the talmid's cheek. He kept his hand there for a long moment, and said two words.

“My Chaim.”

For the fathers of the Mirrer talmidim, it was no different. They too waited in the hope of hearing an encouraging word about their son, evidence that this gadol was familiar with their children.

One father introduced himself.

“Oh,” said the rosh yeshiva delightedly, “I know your son, he does birchas kohanim near my seat every morning. And by the way,” the rosh yeshiva added with a smile, “he can use a new hat.”

There was a bochur in yeshiva whose older sister was having trouble finding her match, and his father asked him to request a bracha from the rosh yeshiva for the girl. At the annual dinner in America, the father came to greet the rosh yeshiva, and Rav Nosson Tzvi looked at him. “This year, im yirtzeh Hashem, she'll become a kallah.”

Of course, it happened, but that's not what's extraordinary about the story.

At the beginning of a zman, a personable bochur approached the rosh yeshiva. “I know that the minhag is that the rosh yeshiva accommodates every single talmid who asks for a chavrushaft with him, but I feel bad to burden the rosh yeshiva,” he said. “I have a request: I want my 'kevius' to be that each morning, just after shacharis, I will come wish the rosh yeshiva a 'good morning.”

The rosh yeshiva happily agreed.

At the dinner that year, the boy's father greeted the rosh yeshiva and received the following message: “Please tell your son I missed his 'good morning' today.”

A talmid returned to yeshiva after spending Pesach with his family, still feelings pangs of homesickness. He had enjoyed the comforts of home and Yom Tov with his family and it felt strange to be back in yeshiva.

After shacharis, the rosh yeshiva suddenly stopped by his seat. “It looks like your mother fed you well over Yom Tov,” he said.

“And,” recalls the talmid, “that was the moment when I knew that the Mir was my home.”

Rav Aryeh Finkel (right) broke down when the time came to be maspid the rosh yeshivah

A bochur had established a weekly seder with the rosh yeshivah; he’d walk Rav Nosson Tzvi home once weekly and on the way, he’d share a dvar Torah on the parsha. One Friday, at the shmuess, the rosh yeshiva looked around the room until he located that bochur.

“I heard a beautiful thought from a good friend of mine this week,” he said, before sharing that vort.

There was a bochur who was a late riser, resulting in his repeated tardiness at first seder. His chavrusa finally told him that if he arrived after nine-thirty, he wouldn't learn with him.

One day, the bochur arrived at nine-thirty-two, and the chavrusa stood firm, refusing to learn. The bochur begged for compassion, but the chavrusa was steadfast. They argued and eventually agreed to a “din Torah,” to be adjudicated by the rosh yeshiva.

“If someone would call you each morning before Shacharis, would it be easier for you to wake up?” asked the rosh yeshiva.

The bochur said that it would.

Someone called him the next morning: Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Mirrer rosh yeshiva.

The rosh yeshivah also learned with him for a few minutes after davening, a minhag he repeated every single morning throughout that long winter z’man.

The image of the rosh yeshivah gripping his shtender and

valiantly trying to remain standing as he delivered shiur

inspired a generation of talmidim

An American bochur came to learn in one of the yeshivos of Eretz Yisroel, and upon his arrival, it became evident that, despite what he’d thought, he hadn’t really been accepted to that yeshiva. Apparently there had been a misunderstanding.

Humiliated and disappointed, with no options, he took his friend’s advice and came to the Mir for Elul z’man, hoping that the situation in his yeshiva of choice would be resolved in the interim.

He sat in the great Mirrer beis medrash, not having formally registered, when he felt the rosh yeshiva looking at him. Their eyes locked, and Rav Nosson Tzvi came over to greet him.

The boy jumped to his feet and introduced himself, stammering out an explanation of how he came to be learning in the Mir.

Rav Nosson Tzvi listened to his story, and when he answered, his voice was filled with wonder. “How could it be that any yeshiva didn’t accept a boy with a smile like yours?”

The bochur knew that he’d found his place – and a rebbi for life.

One year, just before Chanukah, a bochur approached Rav Nosson Tzvi and asked the rosh yeshivah to dismiss him from the dormitory. He explained that, in response to a sheila about bochurim having a chiyuv to light Chanukah candles in their dormitory rooms, a prominent posek had offered a solution: the yeshiva administration should take away dormitory rights for the duration of Yom Tov.

Rav Nosson Tzvi argued the psak. “We never did it that way here. I don’t want to say that.”

“But rosh yeshiva, it’s just the words, it doesn’t mean anything; no one is being kicked out of yeshiva. Why can’t the rosh yeshiva just do it?”

Rav Nosson Tzvi shook his head, no. “The hargasha bothers me, to say the words that a bochur has to leave the yeshiva…I can’t do that, every bochur is welcome here. It’s home.”

The rosh yeshiva had a special minhag on leil Hoshana Rabba. He would sit in his sukkah along with Rav Aryeh Finkel and Rav Binyamin Finkel and together, they would learn the first mishna in the mesechta that the yeshiva would be learning over the winter zman.

It was an experience.

“Hashutfin,” one would begin, and another would review the shittos of Rashi and Tosafos, the third mentioning the Rosh’s view. Each word in the mishna was analyzed this way.

A Canadian alumnus who had helped the yeshiva throughout the years and grown close to the rosh yeshiva would often spend Sukkos in Eretz Yisroel. He happened to come visit the rosh yeshiva in his sukkah during this Hoshana Rabba session, and was moved by the beautiful scene, the joy of three gaonim treasuring each word, each nuance of a mishna. The next year, he made it a point to be there as well, soaking in the sublime atmosphere in the rosh yeshiva’s sukkah.

This past Sukkos, Rav Aryeh Finkel felt unwell, so the rosh yeshiva decided to fulfill the annual minhag in Rav Aryeh’s sukkah. But before he left his home, he asked his driver to contact his friend from abroad and inform him of the change in location.

Just a Little Bit More

Rav Nosson Tzvi was a master motivator, able to reach and draw extraordinary strengths from within his talmidim.

Years ago, as a young man, he was stricken with a painful and debilitating illness that should have sapped his strength and limited his growth. In fact, he once confided to a close talmid that even when he lay in bed at night, his physical condition allowed him no peace. But instead of stunting his dreams, the pain forced them to grow more expansive. “If I have no menucha anyhow, if I can’t sleep,” he said, “I may as well think of more ways to spread Torah.” His dreams weren’t just of more buildings, more talmidim…but of developing bigger talmidei chachamim as well.

Mendy was one talmid formed from the substance of those dreams.

He had come to the Mirrer Yeshiva after several other yeshivos hadn’t worked out for him. He decided to take advantage of the Mir’s relatively easy acceptance policy and registered, entering the rosh yeshiva’s room for his bechina.

Mendy introduced himself and the rosh yeshiva held his hand tightly. There was a certain paternal warmth that emanated from the rosh yeshiva that was comforting to Mendy: it had been a while since a rebbi had looked at him that way.

Somehow, despite Mendy’s weak ambitions for himself, he was drawn to the rosh yeshiva; the way the rosh yeshiva looked at him made him feel like a star talmid, and he began to see success in his learning.

It was the middle of the winter-zman, at the time when the initial enthusiasm has usually faded and Pesach bein hazmanim is a distant blip on the horizon. The ever-innovative rosh yeshiva, eager to invest his talmidim with renewed vigor and energy, announced a new initiative; he wanted the bochurim to commit to learning twelve hours each day.

He called a public shmuess and shared his vision. He explained that he really wasn’t asking for that much, just that they use out every second of regular sedarim for learning and only learning. He made it clear that he expected the good bochurim to sign up for this new program, adding their names to a long list that had been hung up specifically for this purpose, which he himself would be reviewing.

The rosh yeshiva said that although the program was only for six weeks, he had no doubt that anyone who made the leap and signed up was guaranteed that the six weeks of heightened dedication would change their life.

The energy and spirit was felt in every corner of the yeshiva, with bochurim sitting in their places and learning – no chatting, no coffee breaks – from nine in the morning until midnight, with only the necessary breaks.

That Friday, after the usual shmuess, the bochurim filed by Rav Nosson Tzvi to wish him a gut Shabbos. Mendy’s turn came and the rosh yeshiva looked up at him.

“I didn’t see your name on that list.”

Mendy was stunned. He wasn’t in that league, far from it. There were hundreds of names there and the yeshiva was exploding with hasmada – what did the rosh yeshiva want from him?

He laughed, hoping that the rosh yeshiva would understand.

The Mir was home, and he had welcomed them.

Now they had to say goodbye

Mendy’s mind was racing. Twelve hours a day? It was inconceivable, but he didn’t see that had a choice. The rosh yeshiva was still grasping his hand, holding tight, waiting patiently.

“Okay, rebbi, I’m in.”

He went to sign his name.

Sunday morning he sat to learn, eager to get through one whole seder. It was hard, but not as hard as he’d thought. It was one o’clock, then three, then seven-thirty then midnight, and through it all, he learned. Day one, then day two, and he went through half a week this way, and it was a new reality, a sense of being above this world, of reaching beyond his own strengths and capabilities, but it was thrilling too. He had no room in his day or mind for anything besides Torah, and even his eating and sleeping seemed somehow part of a schedule of uninterrupted learning, necessary so that he might continue.

On the fourth night, he fell into bed, exhausted, and slept deeply. His dreams carried with them hints and echoes of the encounters and thoughts of the preceding day.

“Chardal, Rashi’s shitta, Reb Nochum’s diyuk…” the concepts swirled around his brain, filling his sleeping hours with the pleasant words of the Gemara and rishonim. He awoke in the morning suffused with an extraordinary joy, and could barely contain himself through Shacharis.

As soon as davening was over, he hurried over to the rosh yeshiva.

“Rebbi, rebbi, I dreamed in learning!”

Rav Nosson Tzvi smiled a knowing smile and rose to his feet. He reached for the hands of his talmid and together, they started to dance.

And as the rosh yeshiva had guaranteed, Mendy’s life was never the same.

He wasn’t the only one; many lives were changed through the rosh yeshiva’s innovative programs, some which called for learning extra hours, others for covering extra ground, and still other for writing in-depth chidushei Torah. But the goal was always the same – to demand just a little more. To be, as the rosh yeshiva would say, “so busy learning there will be no time for anything else.”

He loved the Torah and he loved his talmidim: there was no greater joy in his life than bringing them together. The benches that line the various batei midrash of the Mirrer Yeshiva are packed during seder times, making it hard to obtain sefarim. With this in mind, there are small wooden boxes sticking out of walls and pillars all over, each one with a complete Shas, so that the people on that bench can simply rise and reach out, rather than walk to the back of the beis medrash. The sets of Shas near each bench are symbolic of the fact that there are so many ‘Shas Yidden’ spread out over that beis medrash.

Rav Nosson Tzvi never saw it beneath himself to avail himself to the encyclopedic knowledge of any of the yeshiva’s talmidim. In the middle of an afternoon seder in his house, he suddenly stood up, donning his frock and hat. His chavrusa asked him where he was going.

“I’ll be right back, I’m just going over to yeshiva for a moment to share a chidush with Rav Tzvi Cheshin.”

“Let me call him here,” the chavrusa suggested, knowing the effort that ‘going over to yeshiva’ entailed for the rosh yeshiva.

“No, it’s me that wants his opinion on the shtickel Torah,” the rosh yeshiva insisted.

But, one suspects, there was also a lesson in this too. The rosh yeshiva’s entrance was never unnoticed – in fact, there was a surge of energy in any room he entered – and when he approached Reb Tzvi with his question, it would be noted.

Learning, knowing, mastering…that’s how one becomes great.

THROUGH MY SPIRIT

At a Chanukah mesiba in yeshiva, Rav Yitzchok Ezrachi once turned to the rosh yeshiva and said, “Your leadership is written out in the haftarah for Shabbos Chanukah.” And he quoted the passuk, “Lo b’chayil, vlo b’koiach, ki im b’ruchi amar Hashem Tzevakos, Not through armies and not through might, but through my spirit, says Hashem. (Zecharia 4, 6)”

Rav Nosson Tzvi was weak, he was sick – but his spirit was so mighty, so indomitable.

A yungerman in yeshiva was going through a very difficult time, and found himself unable to concentrate on his learning, so broken was he by suffering. He went to speak to the rosh yeshiva.

“How does the rosh yeshiva manage to learn so much mitoch yissurim, amid his suffering?”

Rav Nosson Tzvi looked at the yungerman and answered, “I don’t learn Torah mitoch yissurim, I learn Torah mitoch simcha, amid joy!”

Rav Chaim Kamil once met a talmid of his own talmid, Rav Nosson Tzvi, and told him the following.

The Radak explains the words ‘orech yamim’, length of days, as referring to one who hasn’t experienced yissurim.

Is there a person in this world who hasn’t suffered, Reb Chaim asked. Can anyone, regardless of age, truly say they haven’t experienced yissurim?

“The answer,” said Reb Chaim, “is that there are people who have trials and struggles, but they don’t feel them; hey rise above them, reaching a place where the pain doesn’t reach them. These people simply don’t have yissurim. And Rav Nosson Tzvi is such a person!”

A talmid had a chavrushaft with the rosh yeshiva each Friday afternoon. On erev Shabbos Va’era, he showed the rosh yeshiva the words of the Ohr Hachaim Hakodosh on the passuk that says that B’nei Yisroel in Mitzrayim were unable to listen to Moshe Rabbeinu, “m’kotzer ruach va’avodah kasheh, from shortness of spirit and hard work.” The question is obvious: how can someone be too overworked, too oppressed, to hear tidings of their own impending release?

The Ohr Hachaim writes “ulai, ltzad shelo hayu b’nei Torah”, perhaps this was so because they had not yet received the Torah, so they lacked the tools to rise above their suffering. Torah would have expanded them, allowed them to have room in their hearts for something besides their heavy workload.

Rav Nosson Tzvi was visibly moved by the piece, and thanked the talmid. “Why didn’t you show me this before the shmuess?” he asked.

Nine years later, the rosh yeshiva was on a visit to Lakewood, where this talmid was a successful rebbi. The talmid brought his class to the rosh yeshiva on a Friday, which happened to be erev Shabbos Va’era. Rav Nosson Tzvi spoke to the boys, and then turned to his talmid for a moment of private conversation.

“Rosh Yeshiva,” said the talmid, “nine years ago, today -”

Rav Nosson Tzvi interrupted him, eyes alight. “The Ohr Hachaim Hakadosh? You think I’ve forgotten it?”

Torah gives the tools to rise above suffering, expands man beyond his situation.

To a world of no yissurim.

A CULTURE OF HARMONY

One of the most remarkable features of the yeshiva Rav Nosson Tzviled was the chinuch it offers in another area: shalom. The Mirrer Yeshivah is marked by a culture, an atmosphere of harmony.

There are many roshei yeshiva, maggidei shiur and mashgichim who serve six thousand talmidim: v’nosnim be’ahava reshus zeh l’zeh, they lovingly allow one another to fulfill their missions.

Rav Nosson Tzvi fostered a culture where others could grow and develop, where there was a market for the talents of a wide variety of talmidei chachamim: chaburos in lomdus and chaburos for bekius, vaadim in halacha and mussar, shiurim in English, Yiddish and Hebrew.

The Mirrer Yeshiva has hundreds of chassidishe talmidim and the rosh yeshiva initiated a special ‘chevra’ for them out of seder hours, giving them space for their own tefillos, and appointing chassidishe mashpi’im from within the yeshiva to lead them. He himself would participate in the occasional chassidishe gathering, his pleasure evident.

He never stopped being awed by the great personalities of the Mir: not just the deceased ones, but even his contemporaries. He would listen eagerly to the shiurim of Rav Refoel Shmuelevitz and the shmuessen of Rav Aryeh Finkel, showing respect and deference for each and every one of the gifted talmidei chachamim that make up the yeshiva’s staff.

The American bochurim would have their own minyan on Simchas Torah night, when it was Yom Tov just for them, with spirited and lively hakafos. If the rosh yeshiva would come in, and he usually did, the excitement would reach its peak, the energy mounting as he danced.

One year, he stood in the middle of the circle and he began to lead the crowd in singing, starting the niggun that defined him.

“Oy Ashrei Mi,” he sang, “oy Ashrei Mi, oy Ashrei Mi she’amalo b’Torah..Fortunate is he who toils in Torah.”

The bochurim enthusiastically joined in, voices reaching the Heavens, part tefillah and part expression of gratitude.

One Shavuos night, he rose to give a shmuess before maariv.

He looked around, smiled, and said “M’darf danken the Ribbono shel Olam, we have to thank Him for the gifts He’s showered upon us.”

The yeshiva was learning mesechta Kidushin, and the rosh yeshiva began to list off the sugyos in order, drawing out each word, his love evident. “Kicha, kidushei kesef, shaveh kesef, chalipin, nasan hu”…He was overcome by emotion, his eyes shining with gratitude for the many gifts he’d received.

And at that moment, every person there understood them as just that: gifts. No one was more fortunate than us, the recipients of that gift, Mesechta Kidushin.

What a shmuess that was.

***

Rosh Yeshiva! It was the thread that joined all your shmuessen and casual conversations, the “haflah v’feleh” with which you reacted to the many, many chaburos delivered around your dining table and the “you made my day” that meant you enjoyed a chiddush.

It was the way your voice would rise when you said the word “lucky”, never tiring of reminding us that we – and anyone fortunate enough to be sheltered in four amos of halacha – were the most privileged people in the world.

Now, a single candle burns on the plain, nondescript shtender at your seat near the aron kodesh. It flickers and dances, sometimes stronger, other times weaker, but always bright.

And in the beis medrash where you taught and inspired and led, a thousand voices fuse in sound.

“What’s the hava amina?”

“The Maharsha asks it.”

“Why did the Rambam leave it out?”

“Noch a mohl, I don’t understand what the Ketzos is saying.”

“The second mehalech in the Rashba…”

They merge, these holy words, no matter the language, and form an enduring song, the song of the luckiest people in the world.

It’s your song, rosh yeshiva…

Oy Ashrei Mi, Oy Ashrei Mi…Oy Ashrei Mi She’amalo baTorah….

The Rebbe Who Taught Me Torah

Eliezer Shulman

The modest apartment on Rechov Yissa Bracha in Jerusalem gave no indication of the distinguished identity of its occupant. Hagaon Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel who was then only a few years into his tenure as rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Mir, resided there with his family.

I was summoned to the house to undergo an entrance examination for the yeshiva. Even after many years, I still remember the table, the tablecloth, and the sefarim that the Rosh Yeshiva was studying. He was immersed in learning when I entered, but he immediately looked up and greeted me warmly. At that moment, I froze in my spot. Young boy that I was at the time, I had been told many things about the Mirrer Yeshiva and the great man who headed it. But there was one thing that no one had told me—that he was stricken with Parkinson’s disease, which caused his whole body to tremble. My tongue froze in my mouth.

We began a short conversation, and the Rosh Yeshiva wanted to hear about the previous yeshiva where I had learned and why I wanted to come to the Mir. After a few minutes, he suggested that I return to be tested the next day. A long time later, I found out that he had to change his daily schedule for that purpose.

When I entered his home the next day, I was already prepared for the sight that awaited me. The conversation flowed. At the end, I was told, “You have been accepted.” I spent the next five years within the hallowed halls of the yeshiva. They were five years during which I, like all the students in the yeshiva, witnessed a daily demonstration of what it means to love the Torah and to derive joy from the Torah, and just how much that love and joy can overcome all human limitations. Regardless of how the Rosh Yeshiva was feeling, he came to the yeshiva even when he was suffering terribly from his illness.

No matter how he was feeling, we saw the Rosh Yeshiva every day, grasping the iron rail alongside the stairs and pulling himself upward, stair by stair, with a willpower as strong as steel, until he reached the beis medrash. The Rosh Yeshiva would enter the beis medrash perspiring, but always with a smile on his face. Once there, he would straighten himself and march inside to his seat, where he would sit and immerse himself in learning.

Every shiur klali that the Rosh Yeshiva delivered was filled with ahavas haTorah. He would climb onto the podium with strength he could not have possessed. His entire body would shake and move about. He would grasp the shtender with all of his might, his fingers locked onto it, and then he would catch his breath. A minute would pass, sometimes two minutes, with the main hall of the yeshiva enveloped in total silence. Only the sounds of the Rosh Yeshiva’s breathing would pierce the air. Then, in a weak voice, with the microphone held close to his mouth, he would begin explaining the Gemara. As the minutes passed, his voice would grow stronger, his weakened body would regain some stability, and in my mind’s eye it appeared that he began to float up above the floor. He would explain the Gemara and its commentators and then introduce a new approach, a path through the sugya that was the only logical conclusion.

Then the shiur would end. All at once the Rosh Yeshiva would slump over. With his fingers still grasping the shtender and his energy depleted, he would make his way down the stairs at the side of the podium toward his place on the eastern wall. Feebleness would be evident in his posture, his face pale and his entire body trembling.

But during the davening following his shiur, it was as if a new person had taken his place. He stood in prayer like a servant before his master, like a son pleading with his father. When he said Shema Yisrael, it was with his entire being; his voice resonated with love for Hashem.

There isn’t a single student in the yeshiva who did not experience moments when the Rosh Yeshiva gave him “tools” for life—to each in accordance with his own needs and his own level. The empire of Mir grew, expanded, and developed, but he knew everything that was taking place within it. Nothing escaped his notice. That mighty heart, which was overflowing with love for the Torah and his students, could not bear the fact that the yeshiva had not been paying the avreichim. The Rosh Yeshiva’s health did not improve, but he continued to persist in traveling abroad in order to keep the yeshiva running. His family worried about him, the yeshiva administration was concerned, the gedolim begged him to stop, but he felt that the burden rested on him. “It was mesiras nefesh for the Torah,” everyone said after his great heart collapsed under the weight of his burdens, and I could think only of the kiddush Hashem that resulted when his exalted neshamah left him.

It was love for the Torah until the very last of his strength had been absolutely, wholly depleted.

***

Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was born in Adar of 1943 in Chicago, Illinois, to Reb Meir and tblc’t, Mrs. Sara Finkel. Reb Meir, a caterer, was a grandson of the Alter of Slabodka, his own father- the Alter’s son- having emigrated to America years earlier.

Young Nosson Tzvi attended the Chicago Jewish Academy, then later the Skokie yeshiva. As a teenager, his mother took him to visit Eretz Yisroel, where his great uncle, Rav Eliezer Yehuda, had reestablished the Mirrer Yeshiva.

Rav Leizer Yudel saw the potential in the all-American teenager, drawing him close. He eventually succeeded in convincing the boy’s parents to leave him in Eretz Yisroel for one winter zman- enough time to introduce the boy to the thrill of serious Torah learning.

In later years, Rav Nosson Tzvi would frequently recall the baseball-cap wearing, sports-loving teenager that arrived here, sharing his story with groups of visiting American teens.

Nosson Tzvi learned with great dedication, rising through the ranks of the yeshiva. In time, Reb Leizer Yudel selected the American as a chasan for his oldest grand-daughter, Leah, daughter of his son Rav Beinish. (Rav Beinish had five daughters, each of whom married Americans: Rav Nosson Tzvi, Rav Binyamin Carlebach, Rav Nachman Levovitz, Rav Yisroel Glustein and Rav Aaron Lopiansky.)

After Rav Leizer Yudel’s passing, Rav Beinish was appointed rosh yeshiva, and his son-in-law, Rav Nosson Tzvi, led a chaburah in the yeshiva. The chabura members accepted to learn twelve hours each day, and soon drew the most diligent members in the kollel.

In addition, the English-speaking Rav Nosson Tzvi was an address for the yeshiva’s growing American student body.

When Rav Beinish passed away, in 1990, Rav Nosson Tzvi was appointed rosh yeshiva. He ushered in a period of unprecedented growth for the yeshiva, the student body rising from one thousand to two thousand, then three thousand, and eventually to its present number of six thousand. He opened many new batei midrash and also opened new institutions under the Mir banner, including a Yeshiva Gedola in Achuzat Brachfeld and a Yeshiva K’tana in Ramat Shlomo.

Soon after assuming the leadership, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which would severely impact him, but never stop him. The image of the rosh yeshiva, gripping two shtenders and trying valiantly to remain standing as he delivered shiur, would inspire a generation of talmidim.

His frequent travels on behalf of the yeshiva and his many, many talmidim, left the rosh yeshiva with a wide circle of admirers, from all segments of the community.

His sudden passing on the 11th of Cheshvan threw his yeshiva, and klal Yisroel, into deep mourning. He is survived by his mother, Mrs. Sara Finkel (author of a popular kosher cookbook) his mother-in-law, Rebbetzin Finkel, prominent for her chassadim with the ill and infirm, his dedicated rebbetzin- who invested her every moment in making the rosh yeshiva as comfortable as possible- and his children.

His oldest son, Rav Eliezer Yehuda, was appointed rosh yeshiva at the levaya.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 384)

Oops! We could not locate your form.