The Road through Real Life

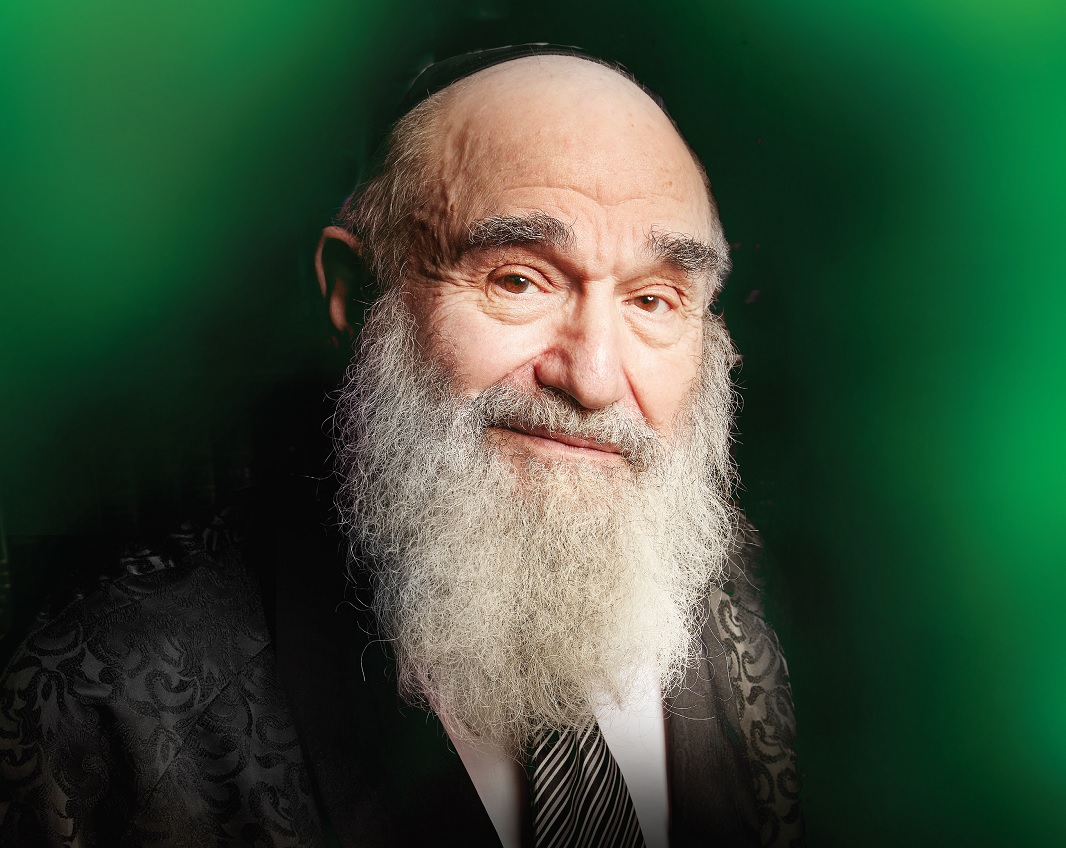

Rav Reuven Feinstein has tapped the clarity born of loss to write a new chapter about the bonds of marriage and true faith

Photos: Marko Dashev, Naftoli Goldgrab

F

our children were born to Rav Moshe and Rebbetzin Shima Feinstein.

Three of them were born in Russia, in Luban.

Just one was born in America.

It’s symbolic, sort of, because Rav Reuven Feinstein has taken so much of what made his father and his older brother, Reb Dovid, great and given it American flavor.

The Luban is still there in Rav Reuven, just with a twist of Lower East Side.

The camp’s name is Camp Yeshiva of Staten Island, which is itself the most Staten Island thing ever: no branded names or plays on words, just a clear, direct statement of what the camp is.

Its rosh yeshivah, Rav Sholom Reuven Feinstein, is a sitting at a small table in his bungalow, a few seforim and a bowl of candy covering its expanse.

He indicates the overflowing bowl of Laffy Taffy and Winkies, saying, “You know, you gotta stay on everyone’s good side, right?” and turns back to my observation about the camp’s name.

“The camp was made for a reason,” he says. “The Rosh Yeshivah wanted something with the camp, it’s not just pshat that we needed a place to spend the summer and this is the place.”

It takes me a moment to realize that the rosh yeshivah of whom he speaks is his father. Reb Moshe.

“The Rosh Yeshivah felt that in yeshivah, bochurim hear the shiur, they see the rebbi and speak to him in learning, but they don’t see him living, they don’t see him interacting with his own wife and children, so camp is crucial. Camp is where talmidim get to see the rebbi in real life.”

And real life is the sugya that Rav Reuven Feinstein has made his own.

Today, Reb Reuven stands at the helm of Yeshiva of Staten Island, one of the most respected yeshivos in America.

I’ve seen him lead question-and-answer sessions at conventions, and inevitably, they’re standing-room-only, and also, they’re marked by repeated laughter. Reb Reuven doesn’t do sound bites or clichés; he answers the questions as they come, barely pausing, as if reading from a paper that lists every possible eventuality.

He answers with a directness and candor that’s uniquely his own. Once, the question was about a parent who overreacted when punishing his child: Should he apologize?

“Yes,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, “of course he should.”

“But how should a parent apologize to a child? What should he say?” the questioner persisted.

“I don’t understand the question.” Reb Reuven peered up at the audience. “He should say, ‘I’m sorry.’ ”

More recently, particularly as his brother Reb Dovid has been unwell, his brachos are sought after, and it can take him a while to make his way across a hotel lobby or chasunah hall. I have no formal data ranking the efficacy of these brachos, but I know enough people who’ve received his brachos and sent friends and family members as well.

But ironically, this gadol, a son of the man Rav Elyashiv remarked would have been the gadol hador ten generations back as well, didn’t travel the usual route to his current position on the mizrach vant of Torah greatness. It was quite a road for Reb Reuven: the road through real life.

After learning at Mesivtha Tiferes Jerusalem in the Lower East Side, where his father Reb Moshe was rosh yeshivah, he continued on to Telshe, in Wickliffe, Ohio, for high school. Then he went to learn under Rav Aharon Kotler in Lakewood.

“The precision and order in Telshe was special, no one was late for tefillos or seder,” Reb Reuven remembers. “Then in Lakewood, I saw a bren for learning that was exceptional, it was like the prewar yeshivos. So in our yeshivah, in Staten Island, I tried to bring in both — the seder of Telshe and the fire of Reb Aharon’s Lakewood.”

I imagine that as Reb Moshe’s son, Reb Reuven must have enjoyed special attention from the Lakewood Rosh Yeshivah. “No, mamesh not,” he say, shrugging, “we spoke in learning, I worked on shiur, but it wasn’t like that.”

There is something in the Rosh Yeshivah’s expression, his tone, that conveys a hint of surprise at my comment. He went to Lakewood to learn. He learned. Special attention — I’m Reb Moshe’s son! — asking for it, expecting it, celebrating it, isn’t his chinuch. He comes from the Lower East Side, where it’s about hard work, grit, and determination, a place of old, worn buildings with temperamental elevators.

“I married a local girl, Shelia Kaplan from a few buildings over, and the naden was good — we ate our meals with her parents.”

It takes me a moment to realize that the “naden,” the dowry of which he speaks, was dinner at the in-laws.

“And I sat in kollel.”

But then, in 1958, Reb Avrohom Kaplan suddenly passed away. The “naden” dried up, and Reb Reuven and Rebbetzin Shelia (her name was pronounced Sheila, but spelled differently because of an error on her birth certificate) had to help support the newly widowed Mrs. Kaplan.

“She made it possible. It was her, it was always her.”

The Rosh Yeshivah pauses for a long moment. “Her” is Rebbetzin Shelia, who passed away two summers ago, and over the course of our conversation, he will pause reflectively whenever he refers to his wife.

Since that time, his shmuessen and private discussions with talmidim have focused on marriage, on appreciating one’s spouse.

“From the way he talks about the Rebbetzin over the last two years, we learn about what it means to have a real bond with a wife,” says a talmid. “And from the way the Rosh Yeshivah talks about HaKadosh Baruch Hu over the last two years, we learn what it means to have real emunah in difficult times.”

Rebbetzin Shelia went to work so that her husband could learn in kollel. It was not a common choice for a young couple in the late 1950s.

“Then she went back to school so that she could get a better job, and her mother watched the children while I was in kollel.”

But the kollel check was meager.

“I believed then, and I believe now, that children should never have to feel like they’re sacrificing for their father’s Torah,” the Rosh Yeshivah says. “Kollel children shouldn’t feel underprivileged.”

And as if remembering how he made extra money saying shiur at night or learning at an early morning kollel, he says the least yeshivish thing ever, but it’s really the most yeshivish thing ever. It’s the world of a family that answers to no one, that doesn’t have to look over its shoulders or worry about how things will be perceived.

“Back then they had these police auctions where you could buy goods for cheaper, so I would get the kids toys from there, trinkets for the Rebbetzin. I would go on Friday afternoon and sometimes I was matzliach…. I remember, I once was dreaming of owning a Megillas Esther, I went around to Judaica auctions, they sold collections from deceased people, and I was pretty good at it. I became a bit of auction expert. I got the megillah.”

The young husband and father wanted to teach Torah, but he had a problem.

No one would hire him.

“Who wants to hire the son of Rav Moshe Feinstein? It means that if it doesn’t work out, you can’t fire him, you’re stuck!” the Rosh Yeshivah explains. “So I was knocking on doors with no takers.”

Finally, a position opened at the Hebrew Institute of Long Island, known as HILI.

“In the Five Towns,” I say, almost to myself, and the Rosh Yeshivah leans forward.

“Don’t ‘Five Towns’ me,” he says. “It was Far Rockaway. It was a more modern school, and they took a chance with me.”

Reb Reuven would take a train to Far Rockaway, spending most of the day away from his family. It wasn’t simple, but there were no better opportunities. This continued for several years, but everything changed when Reb Moshe made his solitary trip to Eretz Yisrael for the 1964 Knessiah Gedolah.

“I don’t know what the catalyst was. My father didn’t go touring or travel much, so being in Eretz Yisrael and seeing the flourishing yeshivah world — not just the growth of the olam haTorah, but the enthusiasm and excitement around it — was likely a pleasant surprise for him. It probably inspired him. Maybe. I can’t say for sure I know what the Rosh Yeshivah was thinking.”

Reb Moshe came back and decided he wanted to open a new yeshivah. There was MTJ, of course, but that was in Manhattan, an older yeshivah, with its unique style. This new yeshivah would be different, patterned after the great yeshivos of Eretz Yisrael.

Reb Reuven chuckles. “My older brother Reb Dovid didn’t want to be rosh yeshivah and I didn’t say no, so that was that.”

Reb Moshe felt that the yeshivah should be outside the city. At the time, the Kamenitz yeshivah was in Woodridge, and the Catskills seemed like a good idea, but it was too expensive. Staten Island was cheap.

“All I knew about Staten Island was that we had gone there on a Lag B’omer trip when I was ten years old, and it was so far that we had to add a nickel at the end of the subway line to keep going.”

But months earlier, the Verrazzano Bridge had finally been completed after decades of planning. It was an arrow of Hashgachah pointing the way forward.

So Reb Reuven went out to Staten Island and started to build.

“From the outset,” he says, “I had good people with me. The menahel, Rav Gershon Weiss, knew how to hire well, how to build a yeshivah. Rav Boruch Saks was also there at the beginning. Baruch Hashem, the yeshivah got a good reputation, people wanted to come. Rav Shlomo Feivel Schustal, who many years later got his start with us, always tells me that those were his most enjoyable years saying shiur.

“But I had another shutaf as well.”

The pause, again.

“The Rebbetzin worked hard, she taught, and then she became a school principal in the Shaare Torah girls’ division, but the yeshivah was her pride and joy. The bochurim knew that when Rebbetzin Shelia was around, they had better hang up their jackets properly, no throwing them over the railings. She had their backs too, she was always petitioning for better meals for them. She wanted them to have a gym, to be able to play ball and enjoy it.”

Reb Reuven cranes his neck and looks out the small window, down the hill, where the baseball field is empty.

He sighs. “These days, I don’t see them playing ball as much, it’s hard to get a game going. Fridays, there used to be a big ballgame, but it’s not the same. Maybe because finding 18 people is hard — I see that they play handball, that only needs four people.”

I respectfully point out that the situation is a result of the yeshivah’s success. In many yeshivos, it’s not a problem to fill up a game or two. Yeshiva of Staten Island has a large enough student body — it’s just that those students would rather be learning.

“Yeah, very good, learning is the most important thing, but you need to stretch a bit,” Reb Reuven says. “I’ll tell you something, my father didn’t want shtenders in yeshivah, only tables, because he held that when a person sits by a shtender, they pull it close to them, it’s sort of relaxing, and the ameilus, the toil, goes down a bit. You’re not as engaged in learning, he felt.

“Now, a yeshivah where we expect the bochurim to lean forward so that they’re all in during seder, don’t you think they need to relax a bit bein hasedorim?”

The Rosh Yeshivah has made some progress. “They’re not big ballplayers, but when they’re chazzering shiur or speaking in learning, they walk around the building, eleven times around is a mile. That’s something.”

The yeshivah continues to thrive, alumni sending their own children, and at this point, grandchildren too: The yeshivah has remained remarkably constant in style and tone, with the majority of its alumni over half a century having remained in learning or chinuch, and those who have gone to work remaining serious bnei Torah.

Reb Reuven deflects the credit for this. “My father started it, it’s his zechusim. We had special rebbeim. Why do we have to adapt and change?”

Once, Reb Moshe was meant to appear at a meeting and he had to send his younger son in his stead. He wrote a note of apology and referred to Reb Reuven, his representative, as an “adam gadol,” a great man.

When I mention this, Reb Reuven reacts with almost bored indifference. “I don’t know. I do know that he called the yeshivah in Staten Island ‘a gutte yeshivah,’ and that makes me happy.”

In Staten Island, the bochurim got to experience proximity to the gadol hador — Reb Moshe came once a week to deliver shiur — but filtered through the sweet, easy unaffectedness of his younger son.

Once a group of talmidim went to the East Side for Shabbos, thrilled to be able to daven alongside and observe Reb Moshe. But to Reb Reuven, it was also a school trip, and he insisted on taking the boys for pizza on Erev Shabbos, so that they would enjoy the excursion.

Even today that same concern is apparent. It’s not uncommon to see the 83-year-old Rosh Yeshivah standing in the back of the beis medrash chatting with a ninth-grader about the food in yeshivah, his family, or where he’s from.

On summer Fridays, Reb Reuven would drive to the Grand Union supermarket to shop for the Rebbetzin. Whichever bochur was hanging around was invited to join the shopping trip, just to catch up and schmooze a bit, and also — of course — to learn how a husband helps a wife on Erev Shabbos. The Rosh Yeshivah has been known to teach boys how to choose cucumbers or peppers, guiding them in how to look for bright colors, to feel that the fruit or vegetable is firm, but not hard. Real life.

But along with the supermarket instruction, there’s an undercurrent of serious avodah to these trips. Once, Reb Reuven had a talmid in the car when it broke down. As they sat at the side of road waiting for help, Reb Reuven remarked, “I thought of seventeen reasons why the Ribbono shel Olam wanted this to happen to me. I hope you’re also using this time to make a cheshbon hanefesh and you’ve come up with a reason why you had to be in the car with me!”

But that focus on the endgame is not a shitah, an approach developed after seminars and intense discussions; it’s the Rosh Yeshivah being himself, a talmid explains, doing what comes naturally to him. If you know enough Torah, if you’ve mastered Shulchan Aruch, if you’re clear about what you to accomplish, then you always know what to do.

Talmidim who have little interest in learning need a special sort of love, a different language. This we know already.

But the ones who have little interest outside learning?

Reb Reuven Feinstein is proving that even they, the metzuyanim, need the warmth and pleasant conversation, the holy East Side normalcy. It’s as if those years in HILI were giving the Rosh Yeshivah tools he would need… for Staten Island.

Miles separate MTJ and Yeshiva of Staten Island geographically, but the two roshei yeshivah share an intimate brotherly bond.

When Reb Moshe was niftar, Reb Reuven accompanied his father’s mitah to Eretz Yisrael, only starting shivah a day after his siblings. Reb Dovid completed shivah a day earlier and returned to yeshivah for Shacharis.

After davening, he rose to speak. It was a big deal. Reb Dovid doesn’t often speak in public, and talmidim filled the beis medrash of MTJ, waiting with anticipation to hear from the new rosh yeshivah. Reb Dovid spoke for under five minutes, sharing a devar halachah from his father and adding a chiddush of his own.

That was it.

But Reb Reuven, who was still sitting shivah, was dejected about having missed it. “Had I known that my brother would be speaking, I would have slipped away just to hear!” he said.

“We don’t speak every day,” Reb Reuven tells me now, “but whenever we speak, we continue the conversation where we left off, we’re very close.”

A few minutes after Rebbetzin Shelia passed away, her broken-hearted husband prepared to leave the hospital and prepare for the levayah. As he exited the elevator, he was met by his brother, who’d come to be with him.

Reb Dovid embraced Reb Reuven, kissing him on the head, and the closest talmidim understood. This was part of the nechamah. No words were exchanged, but no words were possible. There was only love.

At the levayah at Kennedy airport, with the Rebbetzin’s aron en route to Eretz Yisrael, the bereaved husband stood there, swaying back and forth in his grief. A talmid located a chair and brought it over to his rebbi.

He indicated the chair, so that his rebbi might sit. Reb Reuven nodded in gratitude, but his eyes sought out his older brother.

“Thank you,” he told the talmid, “please bring the chair to Reb Dovid.”

I ask Reb Reuven about splitting Reb Moshe’s yerushah — how does one decides who gets the Shulchan Aruch used by Rabban shel Yisrael? The writing pen. The Shas. The chair.

“Reb Dovid decided everything, he told me what was mine, and that was that.”

And that was that.

The bungalow we’re sitting in once belonged to Reb Moshe and his rebbetzin.

Reb Reuven indicates the enclosed porch. “Here’s where my father sat and learned. Some of his best hours of the year were in camp, he sat outdoors and wrote most of the day.”

Rebbetzin Shelia, who was very devoted to her father-in-law, would sit nearby as Reb Moshe learned in case he needed something, with an eye to keeping away those who might unnecessarily disturb him.

“Every so often, my father would suddenly look up and ask how she was doing, just to make sure she didn’t feel ignored because he was so engrossed in learning. Once, she told him he didn’t have to worry about her.

“ ‘It makes me happy to see you learning,’ she said.

“ ‘And it makes me happy that you want to sit here and watch me learn,’ he replied.”

On Shabbos mornings, Reb Moshe would sit outside in the early morning light and lein the weekly parshah with the taamim. But he once overheard his daughter-in-law commenting how much she enjoyed it, and the next week, he didn’t come out to review the parshah.

Later, Rebbetzin Shelia asked why not.

“I heard that you said you listen and I felt bad, Shabbos is your only chance to sleep late…”

She persuaded him that she’d meant what she said, and the minhag resumed.

In the introduction to his sefer, Nahar Sholom, Reb Reuven discusses this connection between his wife and his father, and in his words, one gets a sense that he’s opening the curtain, just a bit, on his own soul.

Those who remember the late ’50s remember how different things were back then. We were not the rosh yeshivah and rebbetzin, but a young couple trying to make ends meet. When I became a rebbi, she was right there with me. When I became an askan, helping found Pirchei and Ohel, she was the first one at my side. When I started the yeshivah under the direction of Adoni Avi Mori v’Rabi ztzvk”l, she was my partner. In the decades that passed, as our roles in the public eye and in our relationship with Hashem developed, she was learning right along with me… our ambitions and goals were one.

Shelia was exceptional in her ability to cling to the words of my parents. She cared for them often and made sure to be around them quite a lot. In the summer, when she would serve my father his tea before minyan, she would speak to the Rosh Yeshivah ztzvk”l about chinuch, hashkafah, derech hachayim….

This is not the place to explain every facet of the similarities between the path of the Rosh Yeshivah and of my dear rebbetzin, but I will leave you with one overarching example….

The Rebbetzin was world-renowned for a few things. Among them was the fact that everyone always said she was so normal. It always strikes people when their rabbanim and rebbetzins actually live in the same world that they live in, and display the mannerisms of regular people. The Rosh Yeshivah ztzvk”l was exactly the same way. The Rosh Yeshivah ztzvk”l was the most normal gadol hador that could be. And this was not by accident — it was a derech that he taught.

I remember at a farher in the sixth grade, he asked the talmidim what a person should do with his time. One boy answered that he should be busy with davening and learning. To that, the Rosh Yeshivah ztzvk”l replied, “You have to play ball too. But play like a Yid.”

Rebbetzin Shelia a”h was truly a star talmidah of his….

In the two years since her petirah, the holy normalcy has been a steady focus, but those who’ve known the Rosh Yeshivah for a long time say it’s always been his avodah.

The examples in his shmuessen have always been relatable and real, recognizable to the listener.

In a shmuess on being over preoccupied with one’s own image, the Rosh Yeshivah reflected, “Many wealthy people would never walk into a deli. It just doesn’t pas for them, even though they would much prefer a pastrami sandwich to whatever fancy fare they’re being served in an upscale restaurant. But those same people, if they happen to see franks at a smorgasbord at Ateres Avrohom, they hurry over, because it’s what they really like, and there, they can get away with it.

“Because of kavod and insecurity, they aren’t really enjoying life!”

In a shmuess on respecting one’s spouse: “I never wanted to buy my wife flowers, they seemed like a bad investment to me, not cheap, and they don’t last that long, and once they start to wilt you have to get rid of them. For what? Spend the money on something practical, I thought. But then I realized that ha gufa, because they’re not practical and have no function, that’s why they express an emotion so well…”

When talmidim are deep in a shidduch relationship, he will ask, “Did you already speak about the important stuff?”

“Well, we talked hashkafah, about family, what kind of life we want to lead,” the talmid will answer.

“Yes, but I mean the really important stuff, like if she likes the air conditioner on or off in the car?”

The talmid will laugh and Reb Reuven will say, “Ah, you’re laughing now? Good, then make sure that in real life you’re also able to laugh about it.”

A talmid came into the Rosh Yeshivah’s office the day after going on his first date and dropped into a chair near Reb Reuven’s desk. It was clear to him that the girl wasn’t for him, but he was wondering how he could bring himself to say no.

“If I say no, won’t she feel rejected? How can I do that? I feel bad for her,” the bochur said.

“Do you feel bad enough to spend the rest of your life with her?” asked Reb Reuven.

“No,” replied the young man.

“Good,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, “so say so now.”

The Rosh Yeshivah’s grasp of Torah is equally broad as his understanding of human nature. Once, Reb Reuven was sitting on a beis din and the to’ein, the rabbinic litigator, quoted one of the Nosei Keilim, a commentator on Shulchan Aruch. Reb Reuven immediately grimaced and challenged the to’ein to show the source inside — which he couldn’t do.

Yet talmidim stand by the door and listen in as the same Reb Reuven — proficient in Shas and poskim — sits at his table, simply being maavir sedra, reading the pesukim with the sweetness and excitement in his voice that’s present during shiur klali.

It’s all Torah, and every word is equally holy.

Reb Reuven’s brachos are rooted in the real world as well. A few years back, Reb Reuven and his rebbetzin were guests at a Pesach program, and on Erev Pesach, the proprietor conceded that it was a difficult year, with fewer rooms sold than usual.

Reb Reuven looked at his watch. “Nu, there’s still time,” he said.

The proprietor nodded politely, but it seemed a strange comment. It was nearly noon on Erev Pesach.

A few minutes later, he got an urgent call. A guest had arrived at a different Pesach program, also in California, but he couldn’t stay there for Yom Tov for personal reasons. He needed to book ten rooms, on the spot.

By the time the sun set and Yom Tov came in, the proprietor had already seen the results of the Rosh Yeshivah’s off-handed remark.

Reb Reuven doesn’t take me around the entire camp, but he’s quite proud of the spacious, attractive new beis medrash that rises ahead, just across from his bungalow.

“I don’t know that too many camps have places to learn that are so geshmak,” he says, “but the real story here is the builders, the ones who made this happen.”

The Rosh Yeshivah’s grandson, Yaakov Guttman, had spearheaded the project, but he did it in a novel way.

“Every year, we have pressure to accept more and more boys into camp, everyone needs a place for the summer, so my grandson took in a large group of working boys. They’re good boys, even if they’re not in yeshivah. They do maintenance here, they help in the kitchen, and many of them helped him with the construction of the building. They’re not mamesh plumbers or electricians, but they were part of it, they were all useful.”

The Rosh Yeshivah looks up at the building. “That makes it a special place. These boys, this team, they learn here seriously every day, and we give them bechinos. Today they’re being tested on hilchos bishul, hatmanah, stuff you have to know if you work around kitchens. There is no such thing as a bad kid, just a kid who didn’t find his path, that’s all.”

Throughout our conversation, grandchildren have come by for candies or to say hello, but he stops now and leans over a baby carriage.

This baby is named Chava Sarah, the first to carry the full name of the Rebbetzin, and Reb Reuven contemplates the peaceful child.

He asks if she’s sleeping well and then asks if the mother is sleeping well. The father too, he adds, everyone should be sleeping well.

Then, after looking at the beautiful beis medrash, he turns to face the baseball field, and smiles.

“The Rosh Yeshivah liked it here so much,” he repeats. “He felt that here, the talmidim could see the whole picture.

“Here,” Rav Reuven Feinstein says, “here, they could see real life.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (1)