“Sing, Moishele, Sing”

It’s a regular feature at museums and fairs celebrating places and eras long gone: a little booth with costumes and props of the epoch. For a small fee, a photographer will snap a black-and-white photograph of a visitor sitting still, assuming the pose and expression of a hardened revolutionary or a dashing English royal.

But look closely at those pictures gracing photo albums or mantles, and you will find the giveaway, the clue that cries “fraud”: the slight embarrassment in the smile, the glasses that say 2010 even as the rest of the uniform says 1910, the small bump of a cell phone under the cape.

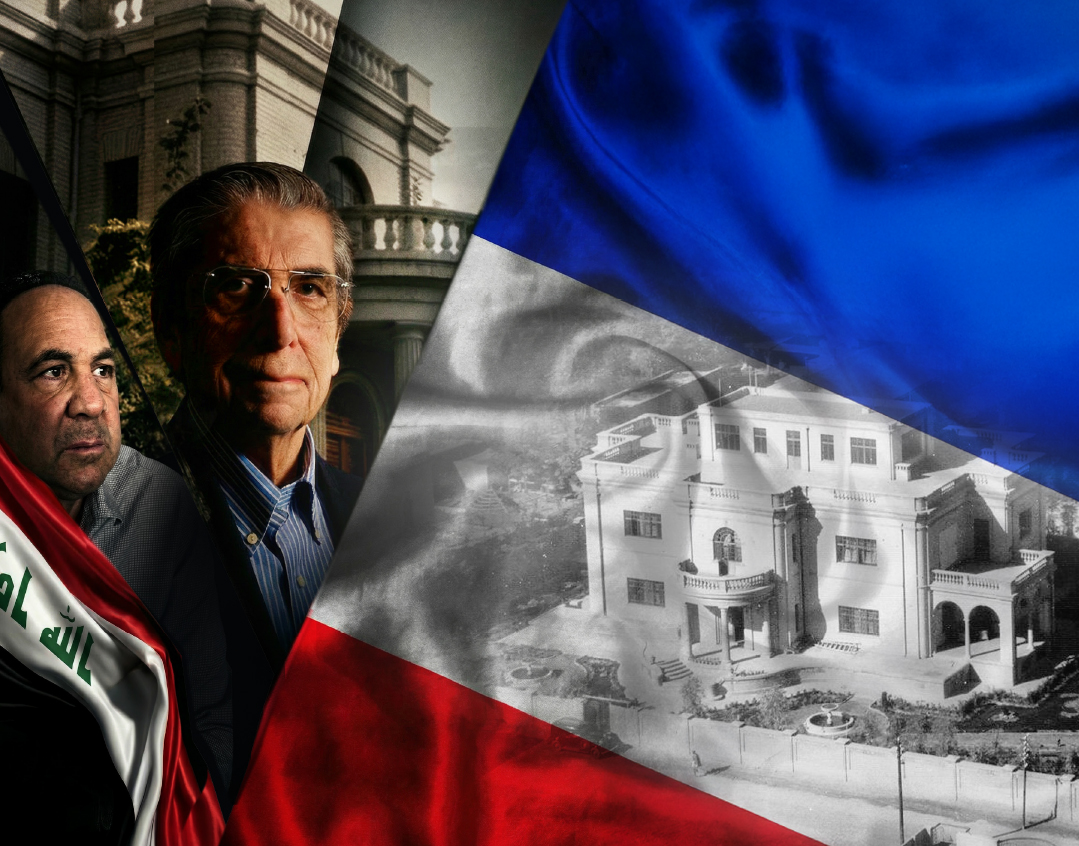

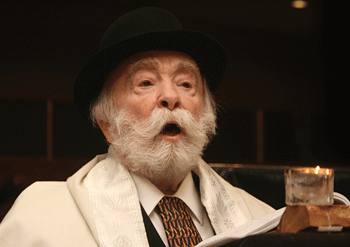

My first thought upon meeting Chazzan Moshe Kraus is that he looks as if he stepped off the set of a production celebrating prewar Hungarian Jewry. But on him, there are no giveaways, no signs that it’s not for real. To be sure, he wears the right clothes for the part: a round, black bowler hat crowns his face, his white mustache is curled at the edges, and instead of a knotted tie, he wears a cravat, the neck-cloth minus the knot.

But his eyes — eyes that are nostalgic and longing, eyes that still reflect the grandeur of the central shul, that bespeak the decorum and dignity of tefillah — tell you that he’s for real.

Breakfast with the Gedolim

“My father was a real ehrliche Yid, a Spinka chassid. Actually, he was a Zidichover, but when his Rebbe was niftar, he had the choice of traveling to the Rebbe’s son and successor across the border, or the Rebbe’s son-in-law, who was in Czechoslovakia, like us. Crossing the border was difficult, so he became a chassid of the son-in-law, the Chakal Yitzchak of Spinka.”

“My father started out as a shochet, but he was too sensitive for the job, so he became a sofer. He had a beautiful handwriting and was quite successful, so we managed. There was always lokshen to eat.” He smiles. “But that was only until I was discovered. After that, we had plenty of money.”

Discovered?

“Yes. When I was about nine years old, someone lifted me onto a table at a chasunah and asked me to sing. So I sang.”

From then on, it seemed Moishele was being asked to sing every night — here at a wedding, there at a dinner.

“I would sing, and people would stuff money into my hand. I didn’t know what do with it,” he laughs, “but I learned quickly.”

Young Moishele Kraus would go to cheder all week long, but would often travel away for Shabbos. Once he reached bar mitzvah and he was able to lead the davening, the demand increased. At the tender age of thirteen, he was better-traveled than most of adults in Ungvar. Where would he go for Shabbos?

“Oh, everywhere. Vilna and Lodz and Nitra and Klausenberg and Warsaw and Pishtan. Wherever I was invited.”

Each town had a central synagogue, and that’s where the boy would lead the tefillos.

“But people from the other shuls would come listen. I once spent Shabbos in Satmar, and the Rebbe, Reb Yoel, stopped in to hear me on the way from the mikveh to his shul.”

Wherever he went, Moishele made it his habit to acquaint himself with the great rabbanim and leaders.

“I accepted a job in Vilna, to sing at a benefit for a yeshivah that was under the leadership of Rav Chaim Ozer, and I merited eating breakfast with him. While we were eating, though, the Kovno Rav, Rav Avraham Dovber Shapira, entered with an emergency issue to discuss, so I didn’t really get a chance to converse with him.”

He also traveled to Dvinsk and ate breakfast with the great Rogatchover Gaon — “but he wasn’t much for conversation; he was learning straight through the meal.”

Once, he arrived at a railway station and saw a great tumult on the platform. At the center of a crowd of Yidden was the diminutive figure of the saintly Chofetz Chaim, and everyone was clamoring for his blessing. Someone shuttled the young chazzan through the crowd to the front of the line.

“He put his holy hands on my head and gave me a brachah.”

Often, if he was in a chassidic town, he would be asked to sing at the tisch.

“I was at the tisch of the Ahavas Yisrael in Grosswardein, and I sang the zmiros along with his son Reb Chaim Meir’l, who would later become the Vizhnitzer Rebbe.”

Moishele’s most memorable and moving experience was in Lublin, where he performed at the great synagogue, and sang a song composed by community’s beloved rav and rosh yeshivah, Rav Meir Shapiro, to the melody of “Zera chaya v’kayama,” with Yiddish lyrics.

The next morning, he was invited to the home of the Lubliner Rav, who asked him to sing the song for him and the rebbetzin.

“So I began to sing, and when I got to the Yiddish part, there were tears coursing down the rav’s cheeks and into his beard.”

The elderly chazzan immediately crosses decades, continents, worlds, and picks up the tune.

Kinder tzim leiben in tzim gezint,

Beiten mir fin Dir atzind

Gitte kinder, ehrliche kinder,

Vus zollen hubben far Dir moirah…

Maturity under the Minchas Elazar

It was time for the cheder yingel to become a yeshivah bochur.

“The Mishnah says ‘hevei golah l’makom Torah,’ a person should exile himself to a place of Torah. The custom was for bochurim to leave home in order to learn. The boys from Ungvar would travel to Munkacz, which was close by, but not close enough for our mothers to call us home to help them schlep packages from the market.”

It was a sort of “student exchange.”

“Boys from Munkacz would come learn in Ungvar for the same reason.”

Moishele remembers entering the room of the Muncakzer Rebbe, the Minchas Elazar, for his entrance exam.

“It was the first time I met my Rebbe, that tzaddik. He looked me up and down and then asked me what I had learned. The rav in Ungvar was a Kohein, so we learned Zevachim. I told the Rebbe that I knew Zevachim, and without opening a Gemara, he began to grill me from all over the masechta.”

The bochur learned exceptionally well in Munkacz, earning the love of the Minchas Elazar.

“What can I tell you, the Rebbe has a reputation as a zealot, and he was one. But we only felt love. He was brimming with warmth; he would embrace bochurim before they left yeshivah, like a father.”

Moishele would often travel away for Shabbos and return Sunday morning, but whenever he spent Shabbos with the Rebbe, he was asked to sing at the tisch.

“Once, my uncle was there and the Rebbe was mechabed me: ‘Moishele, Mah Yedidus.’ My uncle, an outspoken fellow, respectfully told the Rebbe that I had two names, Moshe Shimon. The Rebbe said, ‘I know that, but to me, he’s Moishele, I love him so. So I call him Moishele, and I have Shimon in mind.’$$$SEPARATE QUOTES$$$”

The chazzan looks at me, his eyes misty.

“I am an old man now, but still, people call me Moishele, like a young boy. And when they do, I get happy, because I remember my Rebbe.”

Sometimes, the bochur would hear his name being called — “Moishele, the Rebbe wants you” — and he would hurry to the Rebbe’s room. The Rebbe would ask him to sing for him.

“Sometimes, he would request Shabbosdige songs; he liked to hear Pinchik’s ‘Raza d’Shabbos.’$$$SEPARATE QUOTES$$$”

The chazzan distinctly remembers the Minchas Elazar’s shiurim.

“The Rebbe delivered shiur once a week. The bochurim prepared diligently, perusing all the seforim and meforshim on the sugya and pepper him with questions, but the Rebbe was familiar with them all. ‘That question is in the Pnei Yehoshua, and this svara is in the Chasam Sofer,’ he would say.”

Of particular help to Moishele was Reb Burech’l, the Rebbe’s son-in-law, and father of the present Munkaczer Rebbe, who would review the shiur with the bochurim. In fact, the chazzan remembers Reb Burech’l’s chasunah vividly. There is a much-publicized video of the masses at the wedding. In the clip, one can readily sense the joy and excitement that engulfed the town, the triumphant arches and banners throughout its streets. The Rebbe himself is filmed issuing a heartrending plea to his brothers in America, beseeching them to treasure and safeguard Shabbos.

The chazzan recalls the story surrounding the video and its filming.

“The Rebbe would never have agreed to it, but they fooled him. The production company paid a handsome sum for the rights to film an authentic chassidic wedding, and not just any wedding — this was chassidic royalty. People with ulterior motives convinced the Rebbe that wires and lights were there so that chassidim in America could hear the brachos by the chuppah.”

“Later, the Rebbe found out the truth and borrowed a fantastic amount of money to purchase the original, which is why we only have a clip of a few moments from a film that lasted a few hours. The Rebbe burned the original.”

“At the Rebbe’s levayah,” recalls the chazzan, “I saw one of the wealthiest chassidim, from whom the Rebbe had borrowed the money, stand over the open grave and tear up a piece of paper, dropping the scraps into the hole and saying, ‘Machul lach, machul lach.’$$$SEPARATE QUOTES$$$”

The film gave seed to one of the popular jokes of the era.

“Two of the legendary badchanim had a routine playing off the incident. One badchan was called Chatzi Nezek [a play on the Talmudic term for the payment equaling half of monetary damages], since he was missing half his nose [another play on the term nuz, nose in Yiddish], and the other went by the name Kalman Purim. They had this skit where one asks the other where he’s headed.

‘I’m going to the cinema.’

‘You? To the cinema? But you’re a chassidishe Yid!’

‘Yes, but I’m not going to watch a regular film; I’m going to see footage from the Rebbe’s chasunah.’

‘Still, I don’t think it’s proper for you to be at the cinema.’

“‘I really need to go watch it.’

“‘Why?’

“‘Because I was at the chasunah, and someone gave me a hard kick in the rear. I want to know who did it!’$$$SEPARATE QUOTES$$$”

The chazzan laughs delightedly. It’s still pretty funny, even seventy-five years later.

But then his face darkens as he remembers the dark day of the Rebbe’s levayah, in the spring of 1937. The Rebbe’s daughter, Reb Burech’l’s wife, Frimit’l, had only one child and she was desperate for another. After the burial was complete, she lay down across the fresh grave and began to weep, “Tatte, Tatte. I will not leave unless you promise me more children.”

“It was uncomfortable for everyone to witness her raw pain, and family members urged her to stand up, but she refused. I saw two Rebbes approach, the Chakal Yitzchak of Spinka and the Kossoner Rebbe, and assure her that she would be helped. Only then did she rise to her feet and go home. And, of course, she had quite a few children after that.”

The chazzan sighs deeply.

“I will tell you a story that I witnessed with my eyes, one that will give you a bit of perspective on who my Rebbe was.”

It was just after the Rebbe’s levayah, and a disconsolate Moishele walked through the streets of Munkacz aimlessly, seeking balm for his troubled soul.

He walked by the office of the Rebbi Meir Baal Haness Tzedakah, and saw a small group of people inside.

“Everyone was sitting on the floor, with their clothing torn and their shoes removed. The gabbai, Reb Moshe Goldstein, was telling stories of the Rebbe. He shared an anecdote and provided the background to a conversation I had witnessed.”

In a town near Munkacz, there was a feud between the rav and president. The president was a learned man, and in his efforts to undermine the rav, he instructed his wife to stop asking her halachic sheilos to the rav and to address them to him.

One Friday, the wife was preparing soup for Shabbos when she noticed an irregularity on the leg of the chicken. Her husband was out working and she had no time to wait for him to return. She hurried to the rav’s house and showed him the chicken.

“Kosher” he paskened.

As she returned home, she met her husband coming up the street.

“Where are you coming from?” he asked.

She explained that she had been pressed for time, and was forced to ask the rav her sheilah. The husband asked to see the chicken, and after studying it, he pronounced it treif and insisted she replace it with another. He took the first chicken and placed it in the icebox.

On Sunday morning, a coach pulled up at the rav’s house. In it sat the president, a package in his lap.

“Come,” he told the rav, “we are going to Munkacz.”

Together, the two made the journey and entered the room of the Minchas Elazar. Up on a ladder, sorting the Rebbe’s seforim, stood young Moishele Kraus, watching the proceedings.

“Rebbe,” said the president, “look at what kind of rav we have. He was machshir a chicken which is clearly treif.”

The president unwrapped the chicken and placed it in front of the Rebbe.

The Rebbe examined the chicken. Then he said the brachah shehakol, and ate a small piece of the chicken.

“The president looked crestfallen,” recalls Reb Moishele. “The Rebbe’s act had spoken louder than any words, and the president walked out deflated, in disgrace.

“After they left, one of the Rebbe’s prized disciples, Itche Sanzer [Rav Yitzchok Sternhell, later a rav in Baltimore] asked the Rebbe for an explanation. ‘Rebbe, even if the chicken was kosher, once it was the subject of a sheilah, it was no longer glatt kosher, and the Rebbe is generally makpid to eat only glatt. Why did the Rebbe eat it in this instance?’

“The Rebbe pounded on the table so hard that the seforim jumped, and he looked at Itche. ‘Ihn mentsch fleish iz yuh glatt kosher, human flesh is permitted for one to eat?’

“I had seen that dialogue, but until I heard the background information from Reb Moshe Goldstein, I didn’t know what the Rebbe was referring to. Only after I heard of the arrogance of the president and how he sought to humiliate the rav of his town did I understand. The Rebbe would sooner eat the chicken, even though it wasn’t up to his standards, than allow the rav’s ‘meat’ to be eaten.”

From Prodigy to Professional

The Munkacz years came to an end and the prodigy went to Vienna to study music, planning to make chazzanus a career.

“But the Nazis marched towards me, so I ran to Prague. Then they came there, so I hurried to Budapest. There, they caught me and took me to Bergen-Belsen.”

He pauses, dry-eyed, and shrugs.

“Do I have emunah? Sure I do. I saw enough tzaddikim in my life that I feel the Ribono shel Olam with me, everywhere.”

Our conversation picks up after the liberation, when the chazzan emerged from the inferno alone, having lost his parents, siblings, and his whole world.

No one remembered that he was Moishele the chazzan, notes of song and prayer having been replaced with sighs and weeping.

The broken young man focused on the future and joined what remained of European Jewry, the last leaves on a bare tree, and arrived in Eretz Yisrael.

Feeling utterly alone, he joined the army. His quick mind stood him in good stead, and in short time, he had learned how to construct and take apart a tank.

“So they made me an instructor. You know, I had learned Gemara for years; my head was sharp.”

One day in 1948, he attended the wedding of a friend from the army. They knew that Moishele was a chazzan, and he was honored to recite the seven brachos under the chuppah.

“In those days, the rabbi would officiate and be mesader kiddushin and then a chazzan would take over, chanting the brachos — not like today, where the whole thing is a ‘Purim shpiel,’ with as many people as possible going up there.”

Many things had happened since Moishele Kraus had last performed — few of them positive — but his voice still had the power to uplift, to touch Jewish hearts. After he finished singing, a military-type approached him and introduced himself.

“It was the ramatkal, the army chief of staff, Yigal Yadin, and on the spot, he offered me the job of chief cantor for the Israeli Defense Forces.”

Yadin told the young survivor that he would be the first person to occupy this position; the IDF had never had a chief cantor before. Moishele Kraus from Ungvar took the job, and life once again began to pick up pace.

“I was always busy. There were many, many funerals and memorial services, nebach. But I spent most nights singing for the troops, bolstering their spirits.”

The chazzan filled the position for the two years left in his mandatory service, and then planned to leave the army. He had married in the interim — his wife Rivka was a German refugee who had, like him, come to Israel after having lost most of her family — and wanted to leave the army and work in the private sector, so that he could devote time to his new wife.

But when he came to the army office to sign the release form, there was a message waiting for him: “The ramatkal wants to see you.” There was a military Jeep waiting for him, and he was driven to Yadin’s office. Yadin greeted the chazzan and pointed to two papers in front of him.

“This one is your release form, and if you want to leave the army, you are free to do so. I will sign it for you.

“The other is a renewal of your contract for another two years, and I hope you will accept it. You see, I attend many funerals for our fallen chayalim, and more than once, the mother of the fallen soldier has told me, “We couldn’t find any nichumim, comfort. But when that chazzan sang the Keil Malei, we found ‘nichumim’. I want you to stay on, because you are comforting the grieving mothers.”

The chazzan looks at me.

“So with tears in my eyes, I signed up for another two years.”

The Improbable Transformation

Not everyone viewed his transformation from chassid to army cantor as a positive development.

“One morning, I looked at my calendar and saw that I had a free day. Someone told me that the Satmar Rebbe would be arriving in Eretz Yisrael for a visit, so I set out for the Haifa port, where a huge crowd was waiting. The soldiers kept waving me on, closer and closer to the boat. Then I realized that since I had military plates on my Jeep, I could go on to the actual boat. I figured that it would be an opportunity to get a brachah from the Rebbe, whom I had known back in Hungary. I drove right up to the boat and walked on to the deck. I approached the Rebbe’s room and met Sender Deutsch outside, standing guard. ‘Who are you?’ he asked.

“It’s me, Moishele Kraus, and I want to go in to the Rebbe.’

“‘Like this?’ he asked me, and then I realized that I was in uniform. I prepared to turn back, but just then the door to the Rebbe’s room opened.”

The Rebbe stepped out and looked at Moishele Kraus. He reached out and began to run his fingers over the medals and ribbons on his uniform lapel.

“He was smiling, but I could tell that inside, he was seething. The smile never left his face, though, and he said, as if to himself, ‘A Meenkatcher talmid, a soldier in medinas Yisruel,’ over and over again.”

The Rebbe invited Moishe to join his entourage, and the chazzan accompanied the Rebbe into the waiting car, accompanying him on a visit to Reb Burech’l of Seret-Vizhnitz, who lived in Haifa.

The discussion between the two tzaddikim centered around a dispute that was being widely reported in the news, as to the burial place of Dovid HaMelech. There were many who maintained that the official burial place on Mount Zion was inauthentic, and there were historians on each side of the aisle.

“Vuss zugt ihr, Serete Rebbe, what is your opinion?” asked the Satmar Rebbe.

The Serete Rebbe smiled. “If Dovid HaMelech is on Har Tzion or not is a shema, a question. But that he is not in Williamsburg is ‘bari’, certain” — an allusion to the fact that the Satmarer had chosen to establish himself in America, rather than Eretz Yisrael.

A Four Continent Chazzan

In 1952, the chazzan left the army and he and his wife moved to Antwerp, where he became the chief chazzan for the community.

“We came just before Rav Kreiswirth,” he recalls. “That was a kehillah that knew how to treat the rav and the chazzan.”

Mrs. Kraus experienced health issues and the doctors suggested that she needed a warmer climate, with more sunshine. In 1956, the Krauses accepted an invitation from the Johannesburg community. They were there until 1968, but then the political situation was too difficult, so they moved to Ottawa.

The Canadian capital agreed with the chazzan, and he lives there with his wife until today. He is no longer an active chazzan, but occasionally gives in to the requests of close friends and will enliven a simchah by leading the davening. His presence is welcomed wherever he goes, for Chazzan Kraus has friends across the globe, a network that he and Rivka have formed over nine decades. They are “mechutanim” with so many people, in so many places.

While I was preparing this article for publication, a dear friend, Reb Yitzchak Eisdorfer, who is making an aufruf, mentioned that he couldn’t imagine hosting a simchah without the participation of the chazzan, who comes from Ottawa to participate in Eisdorfer simchahs.

I asked him what his connection is with the chazzan, and he recounted how, several years back, he had to spend a Shabbos in the Canadian capital. He walked for an hour to daven in the “kosher” shul, and when he entered, an older Yid, resplendent in his cantorial vestments, approached and handed him a Munkaczer siddur. Reb Yitzchok, in his shtreimel and beketshe, accepted it.

After davening, the chazzan came over to greet him, asking where he came from — where he really came from, a generation or two back. Upon hearing the name of Reb Hirsch Goldberg, Eisdorfer’s maternal grandfather, the chazzan’s eyes misted over.

“He was my rebbi back in Ungvar, the family lived next door to ours.”

From that moment on, a deep connection was formed.

At the Eisdorfer’s last simchah, the chazzan came to Montreal for Shabbos.

Recalls Reb Yitzchak: “What can I say? A Yid comes in from eighty years ago, filled with the taam and spirit of Ungvar of old. He brings us much more than his musical gifts: he brings us the zeideh, that whole generation!”

Back to Bergen Belsen

Last spring, the chazzan made the journey back to Bergen-Belsen, just as he had five years earlier, to join the ceremony commemorating sixty-five years since the camp’s liberation.

“Sure, it’s hard, but I think back to the last days there, when there were so few of us still standing. My friends and I set out to bury the corpses. I think in the span of a few weeks we buried 15,000 people. We worked all day, intent on giving every single one of them this final respect.”

So now, when the aged cantor stands at the podium and chants Yisgadal v’Yiskadash Shmei Rabba, he isn’t just remembering.

“I am going back there to visit my friends...”

******

There is something about the way he davens, anguish at the suffering he has witnessed mixed with notes of triumph at the heroism he has encountered.

And he saw much of it.

He remembers a Rosh HaShanah in Bergen-Belsen when word spread that 1,400 children were going to be gassed. They wanted one last thing, these children: to hear the shofar blown. The chazzan accompanied the rabbi of Rotterdam to the children’s barracks, where he blew the shofar for them.

They began to dance, 1,400 children, encircling the rabbi and the chazzan.

“Tzavei, Tzavei, Tzavei, Tzavei, Tzavei Yeshuos Yaakov....”

Then the door was flung open and Camp Commandant SS-Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer stood there, incensed.

“Why are you dancing?” he roared. “Soon you will all be dead!”

The chazzan recalls the young boy who answered, filled with sweet confidence. “We are happy, because we are going to our Father in Heaven who loves us.”

And sometimes — even now — the aged chazzan will use the tune of Tzavei for Mimkomcha, in the Kedushah of Shabbos morning. Not the most likely selection, but for the chazzan, it makes sense.

It just makes sense.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 338)

Oops! We could not locate your form.