Shemittah is it’s Own Reward

Photograghy by Avidan Avraham

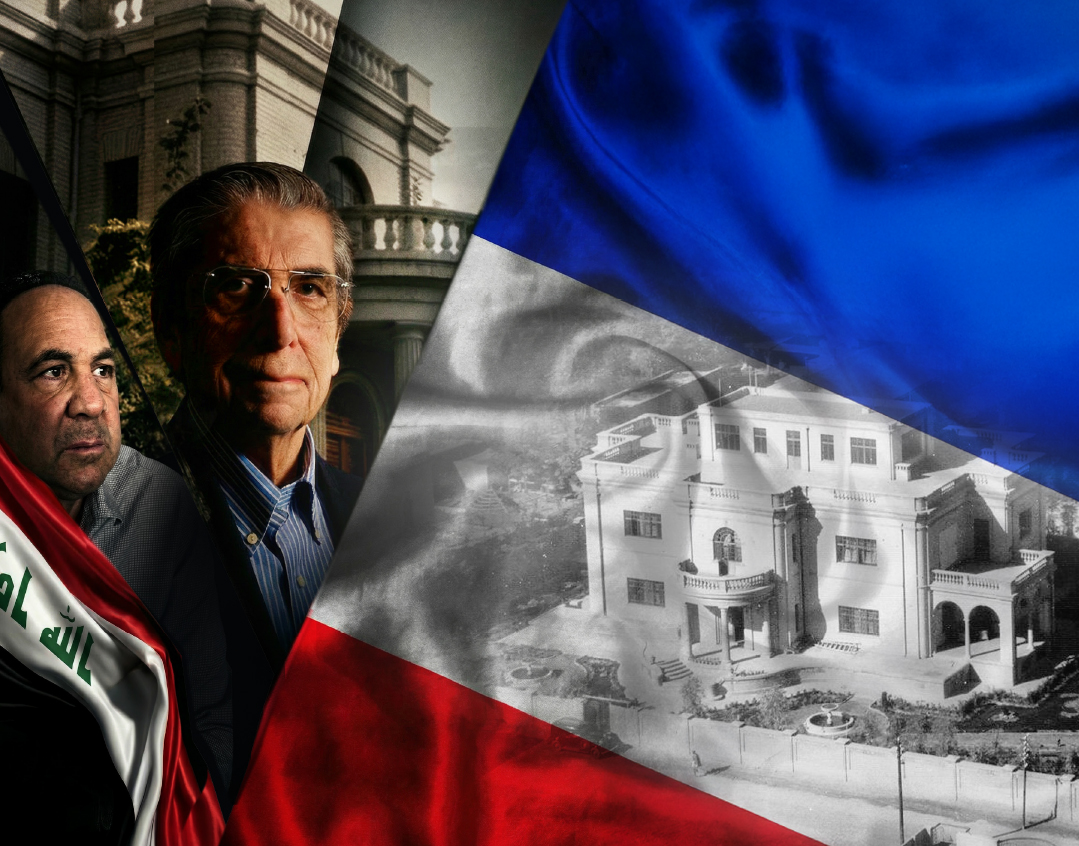

While many farmers plan a sabbatical next year, the odometer on Rabbi Shlomo Ranaan’s roadworthy Toyota spins on overdrive.

He easily logs 50,000 kilometers (31,000 miles) a year on Israel’s winding, and sometimes treacherous rural roads, determined to be a driving force behind the growing trend of more Israeli farmers, including many nonreligious ones, who observe shemittah — the once-in-seven-year mitzvah to let one’s land lie fallow.

To advance his goal, Rabbi Raanan, head of Ayelet Hashachar, has taken on some 20 avreichim to train more than 600 farmers, including some from the most hard-core chiloni towns, where interest in religion is as rare as a summer rain shower.

“These farmers have a deep, and sensitive relationship with their land,” says Rabbi Raanan, who began working with farmers before the previous shemittah seven years ago. “But what always impresses me is that once they make their decision, they observe it with humility and responsibility, while knowing what it will take to avoid succumbing to temptation.”

As head of Ayelet Hashachar, the organization he founded in 1997 to create a united society of religious and nonreligious Jews in Eretz Yisrael, he has visited 800 secular towns, making a mark on 119 of them, either by sending a religious person to lay down roots there, encouraging construction of a synagogue, planning parlor meeting discussions on Jewish topics of interest, or arranging telephone chavrusas for those who want to learn more

While the bulk of the restrictions on agricultural labor don’t take effect until Rosh Hashanah, preparations for shemittah have been underway for months.

Chazal cite shemittah as one “proof” of the Torah’s Divine origin. Who else but G-d could promise unprecedented blessings, and not disastrous losses, by taking a year off from work??

Yet, the Sages tell us that the Babylonian exile was caused in part because the Jews did not observe shemittah properly. If they couldn’t do it, why does Rabbi Raanan pick the seemingly hardest nuts to crack to promote a mitzvah that runs contrary to man’s very nature?

“I want to start from the farthest point, the least likely place, because I know from experience that this will be the easiest,” is how he explains his modus operandi as he drives us to visit four of the 600 “giborei koach” under his tutelage who committed to observing the next shemittah “Their interest is real. It’s intelligent. They’re not complicated and they’re not ostentatious.”

A typical day for Rabbi Raanan might begin in the early morning in the Negev, and end in the wee hours of the next morning in the Jezreel Valley. It’s solitary work, yet it suits his temperament and fosters his goals. “I like to work one-on-one. When I’m alone with someone, there’s no playing politics. I start from a point of mutual respect. I don’t think I’m better, or smarter, or a bigger tzaddik than the people I am trying to teach. I try and see their tzidkus.”

The normal challenges of the shemittah year will be even greater next year, as crops yields are down. Many regions in Israel suffered the driest winter in decades. The day we traveled marked the 57th consecutive day without winter rain — a virtually unprecedented drought.

“What drives you?” I ask Rabbi Raanan.

As we come to a stop at our first destination, Moshav Kidron, he answers. “I started years ago when there was all this talk about giving back the ‘territories’ [to the Arabs]. I thought, what’s going to give us the right to stay? Only if we observe shemittah.”

Or as Rav Chaim Kanievsky shlita said in the name of the Chazon Ish ztz”l at a kenes for farmers that Ayelet Hashachar arranged on Motzaei Shabbos parshas Beshalach: “If there’s no shevi’is, then there’s no motzaei shvi’is.”

Ro’i Bar-Zaccai / Kidron

Kidron, a moshav located about five miles south of Rechovot, was established on 1,000 acres in 1949 by a group of olim from Yugoslavia and Romania. Today, it’s home to about 450 families, including many former Israel Air Force pilots and their families.

When he is not tending to his own groves outside of Rechovot, Ro’i Bar-Zaccai farms seven acres at his father-in-law’s olive groves in Kidron. Right now the trees are bare, but by Pesach they will start flowering, and will be ready for harvest after Succos.

Bar-Zaccai’s first encounter with shemittah came 14 years —two shemittah cycles — ago, when he sought kashrus certification for his olive oil. He approached a local rabbi and signed on to observe shemittah through the heter mechirah.

“I didn’t pay close attention to what I signed,” says Bar-Zaccai. “When I saw that I sold my land to a non-Jew, I was shocked. I said this was the last time I was doing that. I was just starting to learn some Torah back then, and I figured this had to be the opposite of what the Torah wanted.”

Before that shemittah year had ended, Bar-Zaccai’s worst fears were realized when his new, temporary Arab “owners” utilized their access to his orchard to steal 300 olive trees. “Seeing the holes in the ground they left was like seeing a hole in my heart,” said Bar-Zaccai.

But that torment was small potatoes compared to what he experienced before the most recent shemittah, just after he arrived in Kidron seven years ago.

It was Erev Yom Kippur. Bar-Zaccai had just finished his pre-fast meal and was dressed for Kol Nidre, when the phone rang. His own orchard, outside of Rehovot, was engulfed in flames.

“I was standing right here,” says Bar-Zaccai, as he shows me the spot from where he heard the news. “All I could do was say kapparah. I didn’t tell anyone else. I went to shul and tried to put it out of my mind.”

As soon as Yom Kippur ended, Bar-Zaccai was about to leave to inspect the damage when another disaster struck. His daughter was driving out of Kidron with a friend when their car struck a utility pole. The car was totaled, and an entire neighborhood lost power, yet Bar-Zaccai’s daughter and friend suffered only minor injuries.

“It was then that I understood what I meant the day before when I cried out kapparah,” said Bar-Zaccai.

Eventually, an advisor from an arm of Israel’s Ministry of Agriculture met Bar-Zaccai at his blackened olive grove, and he recommended trimming the burned trees to the ground in the hopes of salvaging the roots. Shemittah was in full force, and the melachah of gizum, or trimming, is also restricted. “I knew what I had to do, but I didn’t know if I could do it,” says Bar-Zaccai.

The question was referred to Rabbi Menachem Mendelson ztz”l of Kommemiyus, who dispatched one of his agricultural experts — learned in the relevant halachos — to examine Bar-Zaccai’s grove. Ultimately, the question came before Rav Aharon Leib Steinman shlita. It was Kidron’s unofficial rabbi, Dovid Moshe Bloi, who broke the word of Rav Steinman’s psak to the anxious Bar-Zaccai.

“If you can accept his ruling with simchah and ahavah, you will see unlimited blessing,” said Rabbi Bloi. “If you are angry about it, come back to me and we will find another solution.”

Bar-Zaccai decided to accept Rav Steinman’s ruling to leave his burnt trees alone.

“The wonder was, about two months later, in the midst of the blackened remains, I began to see new leaves, like little green stains sprouting,” says Bar Zaccai. “You wouldn’t believe it, but eventually almost all of the trees revived. I can’t say the yield is as good as it was before the fire, but it’s much better than I ever would have dreamed possible.”

Yitzhak Hod / Carmei Yosef

Carmei Yosef, one of Israel’s most upscale yishuvim, is located between Ramle and Rechovot. Founded in 1974 on 400 acres of agricultural lands, Carmei Yosef is adjacent to the ancient Canaanite city of Gezer, captured in battle by Yehoshua bin Nun, and is home to 457 families.

Entering Carmei Yosef, it is easy to see how this became an exclusive locale. The yishuv is nestled into a hilltop overlooking a wide panorama of open land as far as the eye can see. Cactus plants and an ample array of flowers line the yishuv’s entrance. The purple periwinkles are especially beautiful on this sky-blue day.

Yitzhak Hod farms more than 12 acres of organic vineyards, olive, and lemon groves. Besides making the purest olive oil money can buy, his garage is filled with bottles of liqueurs made from his home-grown almonds, figs, passion fruit, esrog, and carobs. Hod generously doles out samples of all of them on plastic teaspoons.

A crusty Israeli from the old school of sabras, Hod’s father hailed from White Russia and served in the same British prison camp in Eritrea as Israel’s former prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir.

A land surveyor by profession, Hod saw the potential of the Gezer region long before Carmei Yosef was established. “I figured, let’s start a yishuv on the land, so I organized a farmer’s cooperative, signed on a dozen people, and we got the land rezoned for residential development,” says Hod. Carmei Yosef’s first house was built in 1980. The yishuv was originally intended as a mixed development, half professional and half agricultural. Hod fully intended to be one of those professionals, a surveyor, but became a farmer by accident — literally.

One February 5, 1986, Hod was out surveying when it began to rain. He headed back to his car parked on the side of the highway, when another car whizzed by, skidded on the slick asphalt, and collided with an oncoming bus. Hod ended up somewhere in the middle of the wreckage, and suffered serious injuries, forcing him out of the surveyor’s profession. “The injuries impaired my powers of concentration, so work requiring brainpower became difficult for me. But, interestingly enough, I found I was still able to do physical labor, like farming,” says Hod.

Like Kidron, Carmei Yosef also put down roots as a totally secular yishuv, even though today it has two functioning synagogues, one Ashkenazic and one Sephardic. On the surface, shemittah should be the farthest notion from residents’ minds. And the fact that Hod, the secular founder of the secular community, would latch on to the mitzvah may seem astonishing — but not to him.

He was introduced to the concept some 28 years ago, after he was shown a video of farmers relating their miracle stories of the blessings they received after agreeing to observe shemittah. Although for Hod, his decision to observe shemittah was counterintuitive.

“The film turned me off,” he says. “People were saying ‘I succeeded because I observed shemittah.’ I said to myself, ‘this is phony and deceptive.’ The goal seemed to be to try and convince people to observe shemittah to earn a reward. I figured if that’s the case, they’re doing it for the wrong reason. What, if they found they didn’t benefit? They wouldn’t do it again?”

So Hod decided to show them a thing or two about observing shemittah l’shma, and next year will be his fourth cycle as a shemittah-observant farmer.

“When we started Carmei Yosef, people here didn’t know what Shabbos was. On Yom Kippur, people would go to the pool. I’m not religious but at least I knew some things,” says Hod, who also talked at length of how proud he is, both of his two daughters who have both become Torah-observant, and of his own zechus of building a yishuv in Eretz Yisrael.

Elisha Sultan / Ramot Meir

Ramot Meir, population under 800, was originally founded in 1949 by Israeli War of Independence veterans, and named after the American philanthropist Meyer Rosoff, who had purchased the land in the 1930s for his plantations. Rosoff’s original yishuv disbanded in 1965, but was reestablished in 1969 by French olim who originated in North Africa

It’s midafternoon now, and lunchtime seems to have passed us by. The combination of an empty stomach and some of the strong, vintage wines Elisha Sultan places before us for tasting in his winery is having its effect, although it clearly doesn’t take much to animate Elisha Sultan.

Born in Algeria, Sultan remembers taking trips with his father when he was a five-year old, though Algeria’s wine country. Jews would travel the countryside during the grape harvest to find other Jews, whom they hired to trample the grapes.

When Sultan grew up, he served in the French army, and was stationed on a nuclear base in the Sahara Desert where France was conducting nuclear tests.

“I always knew when a test was going to take place, because they would send us to a safe spot, at least 40 kilometers away before the explosion,” said Sultan.

Upon completing his army service, Sultan came to Israel for the first time after the 1967 Six Day War, spending time at several, staunchly secular Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim. It was there that he fell in love with the land and decided aliyah was for him.

Back in France, he received a letter from the Jewish Agency informing him that on his arrival, he was to go to a new moshav that Israel was establishing on the Golan Heights. Those plans suddenly changed one Motzaei Shabbos while still in France, when a fellow Jew handed Sultan a leaflet after Maariv, offering land in Ramot Meir, a new yishuv for Jews of North African heritage.

“That sounded a lot more interesting to me,” said Sultan.

The rest is history. Sultan was one of the first to resettle Ramot Meir after the original community disbanded. Forty-five years later, he avidly cultivates grapes and bottles boutique wines — and brandy — on a little more than two acres.

He expects to harvest his grapes by the end of July, and will have to trim his vines before Rosh Hashanah so they don’t dry out over the winter.

This will be his third shemittah l’chumrah. Coming from Algeria, an Arab nation, the option to utilize the heter mechirah was distinctly unappealing.

“Me, sell my land to the Arabs? No way,” says Sultan.

In his first shemittah, he made his land hefker, and invited people to come in and cut grapes. He’ll do the same with next year’s crop.

Sultan will be just one of two, or perhaps three, Ramot Meir farmers who will observe shemittah, and he sees that as a great privilege.

“What the land yields is what I will get,” says Sultan. “Me and the land. It’s what I wake up for every day. I daven for it. I go to sleep with it. I invest my all in it.”

Moshe Galante / Gvar’am

Gvar’am is a kibbutz in southern Israel, about eight miles from Ashkelon. Home to about 60 families and a few singles, it was established in 1942. In addition to its agricultural prowess, Gvar’am is home to Israel’s largest envelope manufacturer. But it was just last December when the kibbutz sealed a deal to open its own synagogue for the first time in its 72-year history.

Moshe Galante grows wheat, hummus, sunflower seeds, watermelon, and cotton on 1,500 acres. Only about one-third of his land is irrigated, so he is reliant on rain for the bulk of his crops. His decision to observe shemittah next year came after what he called “kibalti boom,” Israeli slang for experiencing a life-changing event, which actually stemmed from his experiment with Shabbos observance a little more than a year ago.

“I had already stopped performing most melachot on Shabbos, but I would go out and water my fields,” says Galante. As he began to feel pangs of conscience, he purchased a computer program that enabled him to preset his irrigation systems from home.

The first Friday he tried out his new program, he set the system so his carrot crop could be watered on Shabbos morning. The weather forecast called for clear skies and he shut his laptop for Shabbos.

That Friday night, it began pouring rain. With the irrigation preset to open the next morning, Galante fretted. Too much water at that delicate stage in the growing process could ruin his carrots.

“I was tempted to turn on the computer and shut the irrigation,” said Galante. “What was the big deal? Press a few buttons? What’s the problem with that?”

Then, his yetzer tov got the better of him. “I said, I’m not going to open the computer.”

After an anxious Shabbos, Galante booted up his computer. To his utter amazement, he saw a blinking red light, warning of a system failure.

“The irrigation mechanism in the field never opened,” says Galante. “My crop was saved.”

Over the next few weeks, he received a few more signs from Heaven that he was on the right track.

“A week later, I’m davening Minchah in my field. People can see me there, so I try to hide between the plants. In the middle of davening and I feel an itch. Little ants were climbing up my leg. I couldn’t concentrate, but all I could do was try to shoo them away. Two weeks later, I’m in another field and I figured I had a half hour to daven. I took out my siddur and turned in the direction of Jerusalem and started davening the Amidah. I looked around and saw a two-meter long snake in the field, coming right at me. I knew it wasn’t poisonous, but I was afraid anyway. Right before the snake got to me, he does this 90-degree turn and hides under my car. All of a sudden, I started laughing that I got over this. Incidents like these incidents strengthen me.”

Three months ago, Galante attended Ayelet Hashachar’s Bnei Brak shemittah kenes. “I found myself in the midst of a sea of 1,000 chareidim. It wasn’t easy coming from an extreme, left-wing kibbutz,” says Galante, although the times are changing.

With help from Ayelet Hashachar, Galante converted an unused kibbutz laundry facility into a synagogue. He received immediate gratification the morning he decided to open it for prayer, along with just one other willing neighbor. Suddenly, a group of soldiers training on a nearby base appeared out of nowhere. One of them saw Galante and asked if this is the synagogue, because he wanted to say Kaddish that day for his grandfather.

“We never had a synagogue until that day,” says Galante. “I have no idea how these soldiers could have known to come here, of all places, to ask for a synagogue.”

Later that week, Galante decided to try his “luck” on a Shabbos morning. The synagogue overlooks the kibbutz’s petting zoo, a popular local tourist attraction.

Galante started talking to G-d. “If there are enough Jews to come and pet animals, can’t you send enough to pray with us?” A handful of curious zoo visitors, plus a few residents, were enough to make the yishuv’s first minyan in its 72-year existence. Gvar’am’s oldest resident, age 97, who came there to live after the Holocaust, held the sefer Torah, with tears, saying he never dreamed he would ever hold a sefer Torah again in his lifetime.

There is still no guarantee of services each week yet, but Galante says he is putting his efforts into it. “Religious topics really don’t interest anyone here,” but again, he sees a promising future.

“The head of the kibbutz stops by every week to remind me to turn on my watering program before Shabbos.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 505)

Oops! We could not locate your form.