It was only around 1970 that a different kind of concert became popular — the frum family show

T

hese days, it sometimes feels like concerts, which we took for granted until two months ago, have become history. Thinking about how the industry will hopefully be restarted sooner than later got me reminiscing about the hundreds of Jewish performers who’ve ended up on stage either at Brooklyn College, Jerusalem’s Binyanei Ha’umah, or anywhere in between. While Jewish concerts, from chazzanus to Yiddish folk music, were performed in shuls and theaters from the turn of the 20th century, it was only around 1970 that a different kind of concert became popular — the frum family show.

This new genre began when a fellow named Isaac Gross, who was then the owner of Neginah Orchestra, came up with the idea of doing large shows geared to families in a more professional venue than the local shul social hall — and his first venture was in the early 1970s with Yigal Calek and his London School of Jewish Song.

After indefatigable Yigal Calek, a sixth-grade yeshivah rebbi-turned-composer and choir director, had released two albums — Ma Navu in 1970 (think “Sali Umetzudasi” and “Al Zeh Hayah Daveh Libeinu”), and Borchi Nafshi in 1971 (with the “tzitzis” jacket cover including real strings), his London Pirchim Choir (which had morphed into the London School of Jewish Song) was invited to spend the summer at Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum’s Camp Sdei Chemed in Eretz Yisrael. I was a kid then, and that summer my family also went to Israel, where I tasted my very first concert — “Camp Sdei Chemed Presents the London School of Jewish Song,” whose albums I already knew by heart. I still remember the thrill of it all.

It was at Sdei Chemed that Yigal Calek first met Neginah Orchestra’s Yisroel Lamm, who became his arranger and conductor. That led to the mega-popular collaboration album with Neginah Orchestra containing such still-enduring hits as “Ashira,” “Ko Amar,” “Chamol,” and “Children of Silence.” Besides the great melodies, Yigal again clinched his niche, choosing words that weren’t the run of the mill pesukim, preferring instead to take profound lyrics from such sources as the Yamim Noraim davening. This third album became so popular that it spawned three world tours.

When Yigal would come to the States with his choir, they would usually sell out four Brooklyn College performances over two weekends — that’s 10,000 seats. And it was no surprise, really. Because Yigal, I can say with confidence, was probably the most creative producer and composer in the history of Jewish music. His genius was not only in the compositions, but also in the way he presented his ideas of what Jewish music should look and sound like. He made sure there were always great, memorable intros, but also made sure that the music would never overpower the choir.

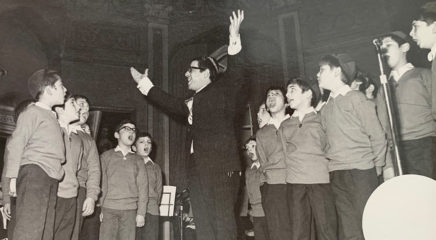

I don’t think I’ve ever seen any choir director enjoying himself so much on stage, prancing around and smiling from ear to ear as he coaxed the beautiful songs out of his young charges. And he was always unpredictable. Sometimes the boys would change costumes five or six times during one show, and he would too. And he’d really ham up the choreography as well. I remember how, for the song “Mareh Kohein,” the soloist came out dressed in bigdei kehunah, singing “Emes, ma nehedar.” And another thing: Yigal made it cool to be in a choir. It was no longer a nerdy thing you did to help the shul chazzan — now choirs were a status, and could even get you on a world tour. He also made it cool to be sincere. The world thought he was just a showman, but I remember spending a Shabbos at his home, together with my longtime partner Suki Berry, when we were on our way to yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael (Suki had played on his London Live album), and the hartzige way he and his sons sang the Shabbos zemiros has stayed with me until today.

Yigal and I are old friends, and as I began writing this, I got the urge to give him a call. He was still energetic and positive, and sounded like he hadn’t aged a day since the last time I saw him. And he was adamant that I follow social-distancing protocol. That’s Yigal, always looking out for others, which is surely one reason he remained so close to all the people he worked with: Isaac Gross, Yisroel Lamm, MBD, Suki, and Sheya Mendlowitz, to name a few.

Speaking at the 25th HASC concert a few years back, Yigal looked around Lincoln Center and said that it was our job to take this magnificent place and use it to give kavod to HaKadosh Baruch Hu. That was always his message, and it still amazes me how a yeshivah boy from Gateshead was able to implant his deep love and passion for Hashem into music we still love so many decades later.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 811)