Diplomat for Life

At 89 years young, Zalman Shoval is perhaps the last remaining member of Israel’s diplomatic corps with insider knowledge of every major geopolitical event from early statehood to the present

Photos: Ezra Trabelsi, GPO, Personal archives

Z

alman Shoval knew he had to hit the ground running once he officially assumed his sensitive post as Israel’s ambassador to the United States in November of 1990. It also didn’t take him long to discover how easy it was to get tripped up out of the starting gate.

Shoval was grappling with two major diplomatic dilemmas that were muddling the US-Israel relationship at that time.

One was the George H.W. Bush administration’s insistence that Israel not retaliate against Iraq, which had begun firing Scud missiles daily into Israel in January 1991, during the Gulf War. The Iraqis were attempting to induce Israel into the war to create a schism between the United States and its Arab allies, who had come to the defense of Kuwait after it was invaded by Iraq.

The Gulf War served to complicate and delay a resolution to the second dilemma — Israel’s immigration crisis — and Jerusalem’s urgent request for $400 million in US funding to resettle hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews who had flooded into Israel as the Soviet Union disintegrated.

In short order, Shoval became the go-to Israeli interview for the US media, and he quickly learned how such opportunities could blow up in his face. During one interview with Reuters, a reporter with an agenda made hay with Shoval’s contention that the Bush administration wasn’t showing enough empathy toward Israel’s urgent needs while glossing over much of the praise Shoval heaped on the White House.

That quote didn’t sit well with Secretary of State James Baker, who eight months earlier had publicly rebuked Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir for what he perceived as the Israeli leader’s insufficient enthusiasm for peace. During a hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Baker was blunt in his assessment of Shamir, giving out the White House phone number, saying: “When you’re serious about peace, call us.”

Baker accused Shoval of “showing remarkably bad faith” and briefly considered declaring him a persona non grata and expelling him for a breach of diplomatic etiquette. Baker summoned Shoval to the State Department for a formal dressing down, which Shoval handled with diplomatic aplomb. As Baker’s right-hand man Dennis Ross described it, “Zalman took it stoically and explained what he had actually said — not what was reported.”

Just a Lot of Noise

In his most nervous moments during the diplomatic crisis over his interview, Shoval wrote that the whole incident brought back memories of the night he crossed the Suez Canal during the Yom Kippur war as an IDF intelligence officer. Egyptian shells were flying, and the sky was full of the rockets’ red glare. “I thought to myself, ‘a lot of noise, but it won’t harm me.’ That’s how I felt in those difficult days.”

Shoval, who celebrated his 89th birthday at the end of April, related that story as well a lifetime of personal, political, and diplomatic memories in his new autobiography: Jerusalem and Washington: A Life in Politics and Diplomacy (Rowman and Littlefield, 2018).

“Diplomacy is not only a profession,” writes Shoval “but also a character trait, behavioral ability, and a way of interacting with others, finding ways of understanding the other, not only on state and political matters, and finding ways that will satisfy you (albeit not always fully) without entering into a bitter confrontation with the person facing you, without making him lose face or presenting him as a loser.”

Shoval’s career traverses the entire lifespan of the state of Israel. He has been instrumental in policymaking and communicating Israel’s foreign policy to the international media and foreign diplomats since the 1970s, when he served as deputy foreign minister under Moshe Dayan.

When Israel’s first prime minister David Ben-Gurion retired from politics in 1970, it was Shoval who assumed his Knesset seat. A few years later, Shoval was a cofounder of the Likud Party. As head of what was dubbed the foreign information activities desk, Shoval crafted a kinder and gentler image for the newly elected Prime Minister Menachem Begin, whom the foreign press excoriated as a terrorist because of his past as a commander of Etzel, also known as the Irgun, a Jewish paramilitary organization whose goal was to oust the British from Palestine and pave the way for an independent Jewish state.

Shoval initiated meetings with foreign correspondents, explaining that there are two Begins — the stormy, radical preelection party leader and the responsible, composed prime minister. Almost 25 years later, Shoval performed the same feat when Israelis elected Ariel Sharon as prime minister in 2001. While the global media portrayed Sharon as “a man who eats Arabs for breakfast,” Shoval gathered a group of influential Israeli ambassadors in an effort to calm fears in foreign capitals, claiming Sharon would take a pragmatic approach. He also correctly predicted that the US, under President George W. Bush and a more conservative Congress, would take kindly to Sharon.

Shoval held down his post at the foreign information desk throughout the 1978 Camp David peace treaty with Egypt and subsequently served as Israel’s point man at almost every major international peace conference, including the Wye Plantation conference in 1998, the 1991 Madrid Conference that followed the Gulf War, and the Oslo process, which Shoval opposed. Even today, a wide range of American and Israeli officials still seek Shoval’s advice, including Prime Minister Netanyahu, with whom Shoval worked closely in the 1990s when Shoval served as US ambassador and Bibi was deputy foreign minister.

M

y interview with Shoval followed his return from a long book tour to the US and Europe. The venue was his office at the Export Investment Corporation in Tel Aviv’s Shalom Mayer Tower. His father-in-law, Moshe Mayer, founded the corporation in 1957 as the “Export Bank” and Zalman, who had married Moshe’s daughter Kena, began working as a teller to gain experience in customer relations. Eventually, he gained a promotion to head the bank’s foreign currency operations. From that position, he helped finance some of the leading corporations of Israel’s statehood, while acquiring valuable political connections. The Shalom Mayer Tower itself was Israel’s first skyscraper, and when completed in 1965, it was the Middle East’s tallest building.

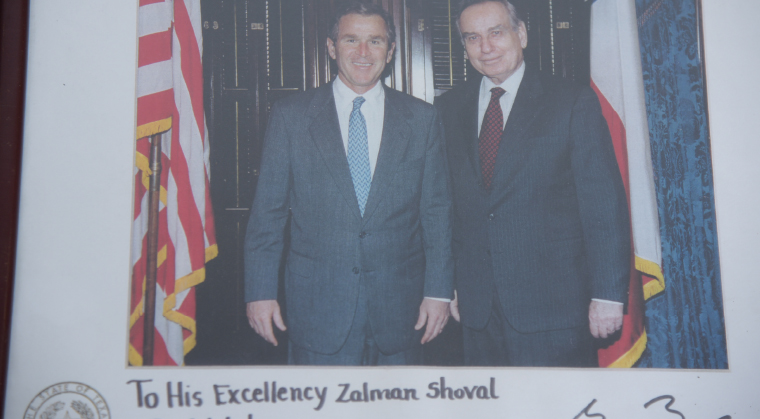

Behind Shoval’s desk are floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, whose shelves are neatly filled with books and periodicals on foreign affairs, history, Knesset proceedings, and finance. Two more walls are lined with plaques, awards, and pictures of him with prime ministers and presidents.

I introduced myself to Shoval, noting that if this had been a Sunday morning 30 years ago, I probably would have been watching Sam Donaldson of ABC News interviewing him for his weekly National Sunday morning talk show, This Week, but today, it was my turn to play Sam Donaldson.

Shoval lit up, remembering those frenetic days, where he would make the rounds of the Sunday morning nationally-televised news programs with no need to remove his television makeup between interviews.

In those days, Shoval was primarily grilled over two subjects: Israel’s stances during the Gulf War and the loan guarantees.

While the US had agreed in principle a few months before Shoval became ambassador to give Israel the funding, Secretary of State Baker viewed the Israeli request as an opportunity to extract concessions from Israel on settlements.

While the US never saw Israeli settlements in Judea and Samaria as illegal under international law (as European nations do), every US administration had opposed settlement in Judea and Samaria since Israel recaptured the territories in 1967. Shoval writes that Baker’s boss — President George H. W. Bush — was the fiercest opponent of the settlement enterprise.

Shoval treats Baker in more benign fashion than Bush. I told Shoval I found this surprising since it was Baker who had once taunted Shamir about his commitment to peace.

“I’ll start with Baker, because a lot has been written that he was anti-Semitic,” said Shoval, who answered questions thoughtfully and thoroughly during our interview in his near-perfect English. “I think he was completely focused on his diplomatic brief, let’s put it like that. Like a lawyer. I don’t think he had sentiments one way or another, not pro-Israel or anti-Israel. He wanted to achieve certain things that he believed in. This was the policy of his boss, who was the president. He was willing to go a long way to accomplish these things, sometimes more pleasant, sometimes less pleasant. But basically I don’t think he had preconceived notions.

As opposed to President Bush.

“Bush — and there seemed to be some evidence for this — had a certain hang-up about Jews. Not ideological or racist or anything like that. We weren’t part of his crowd, the way he saw it. It was difficult for him to find common language with a man like Shamir, who had such a different background. He wasn’t anti-Israel but felt the way Israel conducted its affairs could be potentially damaging to America’s interests. So when Israel bombed the Iraqi nuclear reactor in Osirak, and he was vice president, he really tried to force the Reagan administration to take a very negative attitude toward Israel. He thought that the settlements, and the way Israel behaved, was going to destroy the chances of reaching an agreement that he still believed in and wanted to see crowned during his presidency.”

S

hoval had similar — but stronger — sentiments about President Jimmy Carter, whom he came to know at the Camp David negotiations over peace with Egypt in 1978. Shoval’s role at Camp David was to prepare Israel’s public diplomacy. If the negotiations succeeded, he prepared Israel to articulate the great sacrifices and risks it would be shouldering. If the conference failed, he prepared arguments that would counter Egyptian, and perhaps American, accusations that Israel was to blame.

Shoval saw that Carter leaned more toward Egyptian President Sadat’s positions than Prime Minister Begin’s, but eventually the treaty was negotiated to the satisfaction of both sides and signed.

I asked Shoval to contrast the Jimmy Carter he witnessed with the Jimmy Carter we see today, who expresses positions blatantly hostile to Israel. What made Carter change?

“First of all, I don’t know if he changed. I think that Carter deep down had anti-Semitic tendencies, which he tried to put aside,” Shoval said.

How did you see it or sense that at Camp David, I ask.

“We knew about it much later, really. I didn’t see it at the time. But there were sermons that he made, and his anti-Semitism went back all the way to the Bible.”

Camp David had its advantages, however. One was that both Israel and the Egyptians sought a peace deal. That is unlike the situation today, Shoval says, when neither the Palestinians or Israel seem very enthusiastic about the potential of a peace agreement.

“Any sort of agreement — and maybe this bodes ill for the Trump plan as well — any plan brought about from the outside, which is not supported by the actual players, us and the Palestinians, has no chance really of working.”

Don’t the parties need the US to facilitate, I ask?

“America always played a principal role in facilitating, but facilitating what? Facilitating after there had already been a meeting of the minds and an agreement in principle among the players themselves. Neither the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty was born in the State Department, nor was the Oslo Agreement started from abroad. It was started by the sides themselves. As long as the Palestinians — the Palestinian leadership, at least — has viscerally, ideologically, not accepted the right of the Jewish people to a state of its own, which they haven’t, there’s no chance of a real peace agreement.”

Our interview took place a week before the Bahrain conference, convened by the Trump administration to explore economic development as a precursor to a political settlement between Israel and the Palestinians. Shoval sees some merit in the administration’s approach.

“The economic proposals according to the Trump plan, from what I understand, wouldn’t have negated the Palestinians’ desire to discuss a political settlement later on,” Shoval added. So why did the Palestinians say no?

“We don’t want anything unless we get everything,” Shoval says, explaining the Palestinian position. “It’s an all-or-nothing proposition for the Palestinian leadership. As long as that continues, you can talk about peace all you want. There’s not going to be this sort of final peace we all would hope for.”

T

he conventional wisdom is that Israel risks very little in embracing Trump’s peace plan, even if it contains some objectionable clauses, as long as the Palestinians reject it, because Israel will end up looking like the good guy.

I explored this concept with Shoval in light of the story he related in his book about Secretary of State Baker’s attempt to move Israel and Syria from their uncompromising positions on the Golan Heights by dangling a hypothetical scenario in front of both parties.

Baker, in the early 1990s, asked Israel if it would agree to withdraw from the Golan Heights to the June 4, 1967, border in return for full normalization of relations with Syria. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin took the bait and even put it in writing to Baker’s successor, Warren Christopher. As Shoval writes: “In the years that followed, Syria contended that the ‘deposit’ constituted an official promise by Israel, and that any negotiations in the future should start there. Israel, on the other hand, claimed that the ‘deposit’ was conditional upon our demands on Syria, which were still unmet.”

To show how seriously Israel viewed this risk, Shoval relates that when Bibi Netanyahu was elected prime minister for the first time in 1996, he asked Christopher to return the “deposit” document, and Christopher agreed.

In our interview, Shoval said he has written several articles to the effect that “unless there is something completely objectionable, which I don’t believe there will be in the Trump Plan, from Israel’s point, we should say yes, we agree to it in principle. The details will have to be sorted out in negotiations with the Palestinians, under the mantle of this general agreement.”

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 769)

Oops! We could not locate your form.