Short-lived Knesset, Long-term Problems

Back to the Ballot Box: Special Israeli election coverage

“T

he Greatest Show on Earth” was how the legendary Ringling Bros. dubbed their traveling circus. But last Wednesday night, the greatest show on earth — for young chareidim at least — was at the Knesset.

At 9 p.m., the only people coming through the security scanners at the Knesset entrance were chareidi. The visitors’ gallery high above the plenum was a sea of black and white. Closely following the action below, under the watchful gaze of the Knesset ushers, were dozens of young chassidim and yeshivah students — political pundits to a man.

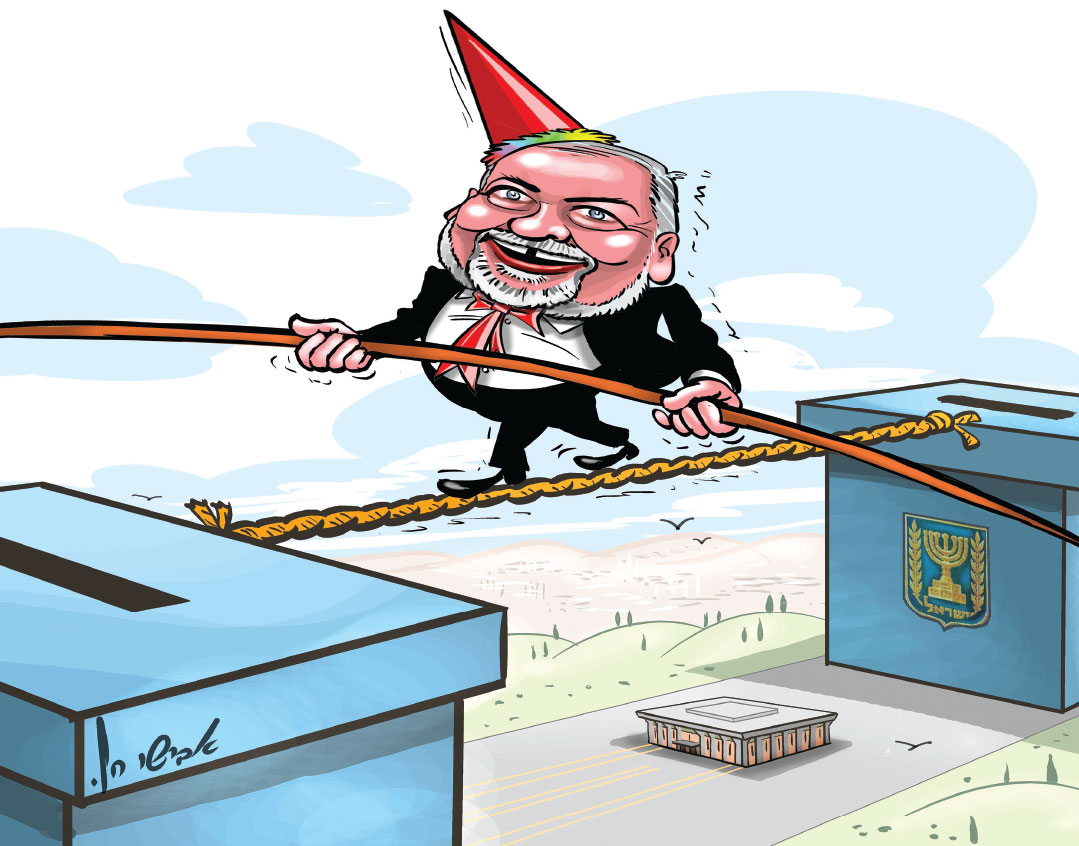

They were there to witness Israeli political history, as Bibi Netanyahu’s hard-won coalition was destroyed by Avigdor Lieberman’s political ambitions, triggering fresh elections only 50 days after being sworn in.

But although the real playmakers were elsewhere — in the prime minister’s residence and Lieberman’s Tel Aviv headquarters — the Knesset was the place to be to understand the long-term messages of this debacle for Israeli politics.

Start with the chareidim. Although for many of the sharp-witted young men there, politics is the ultimate spectator sport — think electoral math instead of baseball stats, the Knesset gallery in place of bleachers — there’s something deeper going on.

The presence of so many chareidim in the Knesset (you can see this every day) is because, uniquely in Israeli society, politics impacts their lives in a very real way. The settler movement has its own parties, but it attracts deep sympathy within the ruling Likud. The Arab minority has ready defenders in Labor and Meretz. But were it not for chareidi political action, 9 percent of Israeli society would be ignored. There is precious little sympathy for the value of full-time Torah learning and limited secular education; the army issue makes the chareidim public enemy number one.

What Wednesday’s showdown proves once again is that chareidi-scapegoating is still a vote-winner. As United Torah Judaism’s Uri Maklev told me the previous day, when many people were still convinced that Lieberman would eventually back down, “This is not about the chareidim. Lieberman has decided to topple Netanyahu, and he won’t accept any compromise. He’s just using the draft issue to get more seats in a new election.” As the clock struck midnight with no deal, that was proven right. Secular and religious politicians get on well in the Knesset; when the cameras stop rolling, they’re on first-name terms. But just as a worn joke can still elicit a laugh if the punchline is well-delivered, chareidi-bashing works even when it’s clearly a ploy.

As the digital screen counted down the minutes until the end of the debate, another factor became obvious. A bird’s-eye view of the Blue and White opposition party reveals its ragbag nature. Moshe Yaalon is center-right, a man who resigned as chief of staff over the Gaza disengagement when many in the Likud remained in government. Benny Gantz is more doveish, and is a political neophyte. Both were overshadowed by Yair Lapid, a pulpit demagogue whose style betrays his background as a TV host. Between calling the Likudniks “cowards,” unwilling to stand up to Bibi, he remembered to put in a plug for Benny Gantz as the next prime minister; it was hard to discern any conviction.

Seemingly the only thing that binds this unwieldy coalition together is a wish to see Bibi’s back. Over the next three months, as the next election battle rages, will the generals stay together with the TV star? It’s the question that will determine whether Bibi’s second roll of the dice is any better than his first.

Heading downstairs to the central area of the Knesset, outside the MKs’ cafeteria, the place is heaving with political operatives. Some hangers-on are trying to wangle their way into the cafeteria, like economy travelers eyeing the King David airport lounge. There’s a stir as a millennial opposition MK brings his newborn baby in a stroller for a spot of late-night politics. A Degel HaTorah delegation walks through looking worried, and talking about a possible deal.

The fragility of Israel’s coalition system is the lesson that many will learn from history’s shortest Knesset. Brought down by the political ambitions of a politician with all of five seats, the talk is of bloc consolidations on the right and left for the next round — to prevent Israel from becoming Italy, in Netanyahu’s words. But in a country so riven by fundamental issues (where else does one side of the aisle want to give away parts of the capital?), fragile coalitions can work out fairer all round. In the search for stable government, there lies a risk of majoritarian rule.

As I walk out to the Knesset carpark at 10:15 p.m., it’s clear that it will take a miracle to produce a government. For all the ease with which Israel’s different demographics rub shoulders here, it’s still too easy to make political capital out of chareidi-bashing. And unless Lieberman is wiped out or the generals’ party breaks up, the draft battle is far from over.

Overheard in the Knesset

Move into a new house in Israel, and someone is bound to ask: “Did you rent or buy?” To non-Israelis, that’s a barefaced invasion of privacy; but for Israelis, personal finance isn’t, well, personal.

The same, I discovered last week, applies in Israel’s parliament. Thirty-six hours before the premature end of the 21st Knesset, the committee tasked with dissolving it ran aground over campaign finance. To fund their election machine, parties take a loan from the government. But since that’s not enough, they take other loans, which they repay using money that winning parties receive, based on their number of MKs.

Ultimately then, elections come down to shekels and agurot. The only thing uniting Likud, Yisrael Beitenu, Meretz, and UTJ at that moment was a shared worry about financing new elections, when the old ones still had to be paid for.

As the assembled MKs and panjandrums took a recess in a corridor near the committee room, I heard Labor leader Avi Gabbay making the rounds.

“Maklev,” he nonchalantly asked of the Degel HaTorah MK, “how much did you borrow?”

“Eighty percent,” came the reply.

“Bitan,” Gabbay demanded of the prominent Likudnik, “how much did you take?”

“Oh, the same — only Meretz took the maximum.”

In Israel, to coin a phrase, the political is personal.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 763)

Oops! We could not locate your form.