Who Knows 4,500?

Photos: Fred Eckhouse

O

ne of the largest collections of Haggados in the world is not behind thick layers of glass in a museum, nor locked away in the dusty stacks of a university library. Instead many of its tomes — encompassing Jewish history from 1485 to 2018 — are housed in Stephen Durchslag’s living room.

Durchslag’s Chicago home overlooking Lake Michigan is bursting with art and life. A visitor’s eye is immediately drawn to artist Shmuel Broner’s brilliant 1840 micrographic work, in which the entire Haggadah has been written in minute form to create the shape of the words “Leil shimurim hu l’hotziam mei’Eretz Mizrayim.” Above it is another piece of art, this one depicting Jewish immigrants to Eretz Yisrael reading from the Haggadah after they escaped from Yemen during Project Magic Carpet. “Just like the Haggadah incorporates the past,” says Durchslag, “I like my home to incorporate the past.”

Walk a little further, and it becomes clear this goal has been met: Durchslag’s living room is like a little museum, complete with a display case in the center housing ancient artifacts, such as several oil lamps from the Second Beis Hamikdash and coins from the times of the Chashmonaim, the first Jewish rebellion against Rome, and the Bar Kochva revolt. In the center of the case is a facsimile edition of the Kennicott Bible, a Tanach written and illuminated in Spain in 1476 — just 16 years before the Expulsion—and considered one of the most beautiful medieval Spanish manuscripts still in existence. Every week, Mr. Durchslag likes to open the case and turn to the page that displays the parshas hashavua.

Sitting beside a table piled high with Haggados, Durchslag explains how his love for collecting began. “I always loved Pesach. In 1984, I was in New York, and I stopped in a Jewish bookstore. I saw a beautiful Haggadah that had been published in 1864 in Ladino [Judeo-Spanish]. I picked it up and after that started collecting them. Now I have the largest private collection in the world.”

From Djerba to Dunedin

Finding his prized Haggados has been a bit like a treasure hunt. “Wherever I travel, I always look for them, and they come up in strange places,” he says. While in Russia on a mission to help support the rebirth of Jewish communities, he met a young man with a Haggadah that had been secretly passed around the Russian Jewish communities in the 1970s for use on Pesach. It conformed to the shape of a person’s leg so it could go in a pocket unnoticed.

Durchslag once traveled with one of his two daughters to Djerba, an island off the coast of Tunisia. The Jewish community of Djerba traces its roots to the tribe of Zevulun; it was established at the time of King Solomon, when Tunisia was an important trading post. Over the centuries, and despite modern challenges, such as when the exiled PLO leaders set up their headquarters in the area, the Jews of Djerba have held on to their identity and preserved their ancient shul and local Jewish school. Mr. Durchslag and his daughter had Shabbos dinner with the rav of Djerba and met with many of the local people, leading to the purchase of several unique Haggados, including one that was locally made.

Another time, he traveled to the United Kingdom in search of a newspaper — a Times of London dated August 17, 1840, which contained the text of the entire Haggadah. This was the time of the Damascus Affair, when the classic libel that Jews used non-Jewish blood to bake their matzos was being propagated. The Times printed the Haggadah in defense of the Jews, to show there was no place in the text that talked about Jews using blood to bake their matzos. Durchslag met with collectors and sellers of old and historic newspapers, but no one had a copy. Refusing to give up, he finally tracked down a copy owned by newspaper seller located in the Canary Islands.

In Israel, he managed to buy a collection of 700 kibbutz Haggados from a man who became a close friend. While attending a minyan in New Zealand, he was offered a signed copy of a Haggadah made for the southernmost synagogue in the world, in Dunedin, New Zealand. Another time, he acquired a 1545 Haggadah that had a manuscript attached to it signed by the censor.

Sometimes, though, the hunt takes him closer to home. For instance, he was once speaking at a shul in Chicago, and afterward a man came up to him and mentioned he had inherited a rare American Haggadah from 1850. Mr. Durchslag bought it from him on the spot.

Surprisingly, the most expensive Haggadah in his collection in terms of current resale value is a Haggadah from the United States. No, it’s not from Maxwell House; this valuable Haggadah was the first one printed in America, circa 1837.

Many Languages of Freedom

The Haggadah is the most frequently published Jewish work after the Bible. Among the 4,500 Haggados in Durchslag’s collection are editions in 31 languages, representing the “B’chol Dor Vador” of Jewish migration throughout the world. One exotic example is a Haggadah in Judeo-Tat, a combination of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Persian spoken by Jews who lived in the Caucasus Mountains in southern Russia and northern Persia. Another is a Haggadah in Afrikaans, which was spoken by Dutch Jews who settled in South Africa.

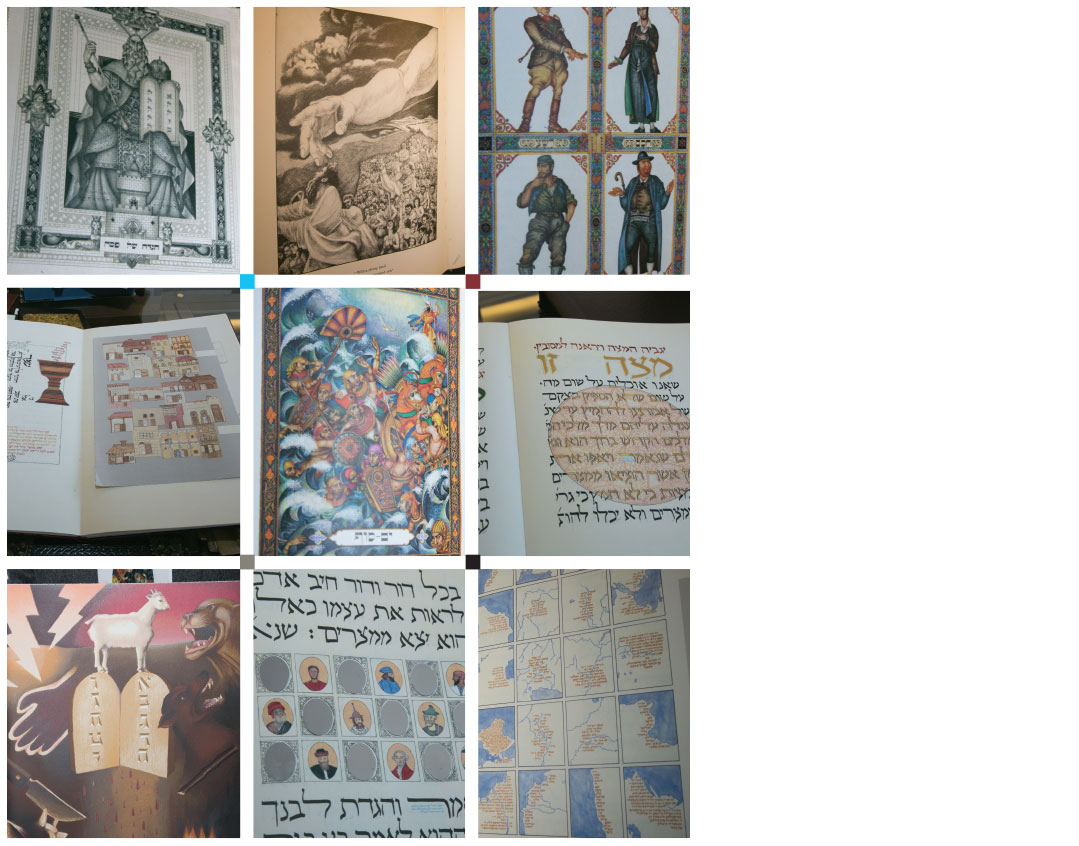

The illustrations and different themes show a great deal about Judaism through the ages as well, says Durchslag. For instance, his collection includes Haggados with commentaries that incorporate themes such as the exploitation of the Jewish working class, poor treatment of teachers in Russia, Communism in 1927, and life in Eretz Yisrael under the British Mandate.

In addition to collecting Haggados, Durchslag is also contributing to Haggadah scholarship. After retiring from a successful 46-year career as an intellectual property lawyer, Mr. Durchslag decided to pursue his passion for Jewish history in a more formal manner and is now a PhD candidate in Jewish history at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Today, he is in touch with scholars all over the world and is doing important work translating many historic Haggados — he is currently rendering the Hebrew and Aramaic 1883 parody “Teachers Haggadah” into English — as well as manuscripts relating to them. He speaks about Haggados and his collection throughout Chicago, at universities where he has loaned his collection for exhibitions, and at synagogues. He has also opened his home to scholars and schoolchildren wishing to view his collection.

“Like Avraham,” he explains, “I like to keep my tent open.”

And, of course, in a private viewing, he has shared some of the highlights of his collection with Mishpacha.

What: Moss Haggadah

Where: Jerusalem, Israel

When: 1987

With its beautiful hand-drawn illustrations, delicate lacey cut-outs, and abundant gold leaf, this Haggadah by artist David Moss is considered one of the most artistically important Haggados created in modern times. Originally from the United States, Moss now lives in Israel, where his work ranges from shtenders to architectural and decorative work for buildings. But this Haggadah has a special place in his heart.

The Haggadah, which was three years in the making, was commissioned by the Levy family. It would have remained a one-of-a-kind masterpiece had not businessman and real estate developer Neil Norry been given a sneak peak of a photographic copy in a Hilton hotel room. Norry was overcome by the Haggadah’s beauty and declared it needed to be shared with the Jewish world — and he was prepared to publish it.

When Moss explained he would agree only if it was done as a perfect facsimile copy — which was seemingly impossible given the many unique techniques and materials he had used — Norry responded that he would find someone somewhere in the world who could reproduce the Haggadah perfectly. He succeeded, and the Haggadah was published in book form in a limited edition in 1987. Mr. Durchslag has a copy in his collection.

What: Mantua Haggadah

Where: Mantua, Italy

When: 1568 (second printing)

During the 1500s, Mantua had a thriving Jewish community. This Haggadah was first printed in 1560 on the press of non-Jewish printer Giacomo Rufinelli; the printing was supervised by Isaac ben Samuel Bassan, a shamash of one Mantua’s synagogues. The Haggadah features Renaissance-style woodcut borders with floral and architectural elements as well as numerous putti (cherub-like creatures) who are often playing musical instruments.

One of Mr. Durchslag’s favorite images is found in this Haggadah: the illustration for “Shefoch chamascha [Pour out Your wrath].” It depicts Mashiach riding on a reluctant donkey, followed by Eliyahu Hanavi, as they approach a city gate. In this instance, Jerusalem looks very much like an Italian city. Some scholars posit that the very palpable yearning for Mashiach depicted in this illustration may refer to the dejected state of Italian Jewry, which had witnessed the burning of the Talmud in Rome just a few years earlier, in 1553, and the subsequent closure of Hebrew printing presses.

What: Zevach Pesach Haggadah

Where: Venice, Italy

When: 1545

When Don Yitzchak Abarbanel sat down in 1496 to write his commentary on the Haggadah, Zevach Pesach, he had already been exiled from Spain and lost three fortunes. He tells the story of his life at the beginning of the commentary. First, he was an advisor to King Alfonso of Portugal, but after Alfonso died in 1483, he had to flee from the new king of Portugal, without his fortune, to Spain.

In Spain, he became an advisor to the monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. When he was expelled along with the rest of Spain’s Jews, he left his second fortune behind. Lastly, he made his way to Naples, where he became an advisor to King Ferdinand I. When Ferdinand died two years later and the Kingdom of Naples was conquered by France, he was forced to flee again, sans fortune. It’s therefore no wonder that Abarbanel included in his commentary some less than loving comments about certain monarchs — and no wonder that many words were blacked out by censors.

Zevach Pesach was printed several times during the 16th century and, says Durchslag, when viewed together, they show the story of censorship during that era. The first Zevach Pesach commentary was printed in 1505 in Constantinople and didn’t have censorship marks because the locals didn’t mind negative comments about Western rulers. However, the one in Venice printed in 1545 has many blacked-out censorship marks because the people there were sensitive to such comments. Lastly, the one printed in Riva Di Trento in 1561 has no censorship at all because by that time, the Counter-Reformation and its accompanying censorship had lost its force.

What: Denavir Haggadah

Where: Holland, the Netherlands

When: 1940

Before their world went up in flames, a group of young Jews were preparing to become chalutzim (pioneers) in Eretz Yisrael. This Haggadah, written in German, was published for their youth movement and used at their Seder. The rare lithographic manuscript contains a map of Eretz Yisrael that highlights where they were going to settle the land and be farmers. The only reason this Haggadah survived the Nazi destruction is because some people mailed it out of Holland before the country was occupied by Germany — making it another example of a Jewish book rescued from the flames of intolerance.

What: Venice Haggadah

Where: Venice, Italy

When: 1609

Published in three different languages — Yiddish, Ladino, and Italian — reflecting the main languages spoken by Venice’s Jews at the time, this Haggadah included many design firsts. For instance, it’s the first Haggadah to illustrate the Order of the Seder, which became a standard feature of many later Haggados. The idea of including a panel of illustrations depicting the Ten Plagues also became standard.

Other innovations include illustrations depicting scenes from the lives of the Avos, the crossing of the Red Sea (with the Jews carrying the remains of Yosef), and other biblical and midrashic themes that hadn’t previously been part of Haggadah iconography.

While the designer of the Haggadah is unknown, he is believed to have been a great Torah scholar. The printer who commissioned the new design, Israel ben Daniel Zifroni of Guastalla, was a well-known publisher of Jewish books. Rabbi Leone da Modena provided the Judeo-Italian translation.

During the 17th century, Venice was one of the most important centers of Hebrew publishing, and the Venice Haggadah is considered one of its masterpieces.

What: Szyk (Schick) Haggadah

Where: New York and London

When: 1940

This Haggadah, with its 48 miniature paintings, is considered the masterpiece by Arthur Szyk, the renowned Polish-born Jewish artist and book illustrator who later emigrated to the United States.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Szyk used his pen and brush to sharply criticize Hitler, yemach shemo, and his policies. He continued to use his artistic talents throughout the war, and his illustrations documenting Nazi tyranny and the murder of Europe’s Jews appeared in American and British newspapers and magazines, garnering support for the Allied war effort.

Szyk illustrated his Haggadah during the years 1934–1936, and in its original conception, his illustrations drew many parallels between the policies of the Nazis and the ancient Egyptians; for instance, the Egyptian taskmasters wore armbands with swastikas. But publishers in prewar Europe were worried by the overt political references and asked Szyk to tone them down. He removed the clearly visible swastikas, but his depiction of the Wicked Son is clearly a reference to the times: The son is a German man dressed in a riding costume, sporting a Hitler-style moustache and carrying a whip.

Szyk went to London in 1937 to supervise the publication of his Haggadah by Beaconsfield Press. The original edition, published in 1940 on vellum and limited to just 250 number copies, included a dedication to King George VI. The English translation and commentary were done by British historian Cecil Roth. With a price tag of 100 guineas, about $500, it was the most expensive new book in the world at the time.

What: Omzsa Haggadah

Where: Budapest, Hungary

When: 1942

Created during World War II, this Haggadah was published by the Relief Society for Hungarian Jews (Omzsa Publishing House). Along with a translation into Hungarian and Egyptian-style drawings, the Omzsa Haggadah also included musical notes for some of the traditional songs, which were arranged by composer Dr. Benzion Avigdor Svoletshy.

Mr. Durchslag reflects on the deeper meaning of this very ornate Haggadah: “It is amazing how it was done in the middle of the war — how in the midst of all this persecution, there was this innate drive to survive both physically and culturally and create beautiful books to transmit our heritage.”

Durchslag also points out that this Haggadah was published on high-quality paper, which was unique for the time. Most Haggados published after 1865 are printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, making them hard to preserve. Ironically, pre-1865 Haggados, which were printed on rag paper, are sturdier and often look newer than later ones. In order to preserve his collection, Durchslag tries to keep his Haggados out of sunlight, makes sure there are no bookworms on them, and handles them carefully. He says that eventually we will be able to easily take the acid out of paper by means of gas, but right now the technology can do only one page at a time, making it extremely expensive.

What: Haggadah in Memory of the Holocaust

Where: New York, NY

When: 1987

Commissioned by Zygfryd and Helene Wolloch of New York in 1981 in memory of their parents who died in the Holocaust, this Haggadah was illustrated by David Wander and has calligraphy by Yonah Weinreb. The shared themes of the Exodus and the Holocaust — slavery, destruction, and redemption — are powerfully juxtaposed and illustrated. There are no depictions of people, for example, to represent the absence of so many lives after the Holocaust. Instead, the Haggadah starts with a pile of lonely, abandoned suitcases to convey the fact that all the people had been killed. Some of the eeriest images are for the words “Blood and fire and pillars of smoke”: Blood is illustrated by blood from murdered Jews, fire by the ovens of the crematoriums, and pillars of smoke by the smoke that rose up from the crematoriums. Another striking illustration is the one for the Four Sons who are depicted as four books: The Wicked Son is a burning book, the Wise Son is a book with writing on the page, the Simple Son is a blank book, and the One Who Doesn’t Know How to Ask is a closed book.

The Wollochs initially exhibited their Holocaust Haggadah at a New York art gallery, where it was so well received that they agreed to publish a limited edition, to benefit the International Society for Yad Vashem.

What: Seder Meah Berachot

Where: Amsterdam, the Netherlands

When: 1687

After the Netherlands won its independence from Spain, it became a magnet for Anusim (crypto-Jews) seeking to flee from the Inquisitions of Spain and Portugal. This sefer, which includes the text of the Haggadah, was published by Jews who had made it safely to Amsterdam and wished to help their compatriots return to Judaism by teaching them the fundamentals of their faith. Along with more traditional blessings, prayers, and piyutim, all of which are written in Spanish and Hebrew, it also includes prayers for when a convert undergoes bris milah and a prayer said for Jews who had been burned at the stake.

Completed but Not Finished

As for his own Seder, most of these Haggados do not make it near the wine glasses. But some years he has done themes, such as Haggados used by Jewish soldiers during wartime. For this particular theme, the Seder guests used historic Haggados that armies printed for their Jewish soldiers. An example is one printed with canvas covers by the German army in 1917 for their Jewish soldiers who were in the field during the holiday.

As for the legacy of the Haggadah with its many different editions printed and illustrated throughout the ages to reflect each era’s unique circumstances, Mr. Durchslag remarks, “It’s the universal story, the idea of freedom from oppression. It’s what everyone is seeking, with the help of G-d. It represents the need to absorb history into the present. One of the wonderful things about Judaism is that it brings our past into our present and brings depth to our lives and hope for our future — that things will be better and, with G-d’s help, we can make them better. The idea of freedom and hope is alive and well with us.”

As Mishpacha’s private showing comes to an end, the Haggados are closed and returned to their places; the wine stains from bygone eras, reminders of the generations of Jews that have used them, are once more concealed within the books’ covers. “This is a treasure that should be shared,” comments Mr. Durchslag. And hopefully it will be, as the story of the Jewish People continues, b’chol dor vador.—

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 757)

Oops! We could not locate your form.