New Beginnings in Vizhnitz

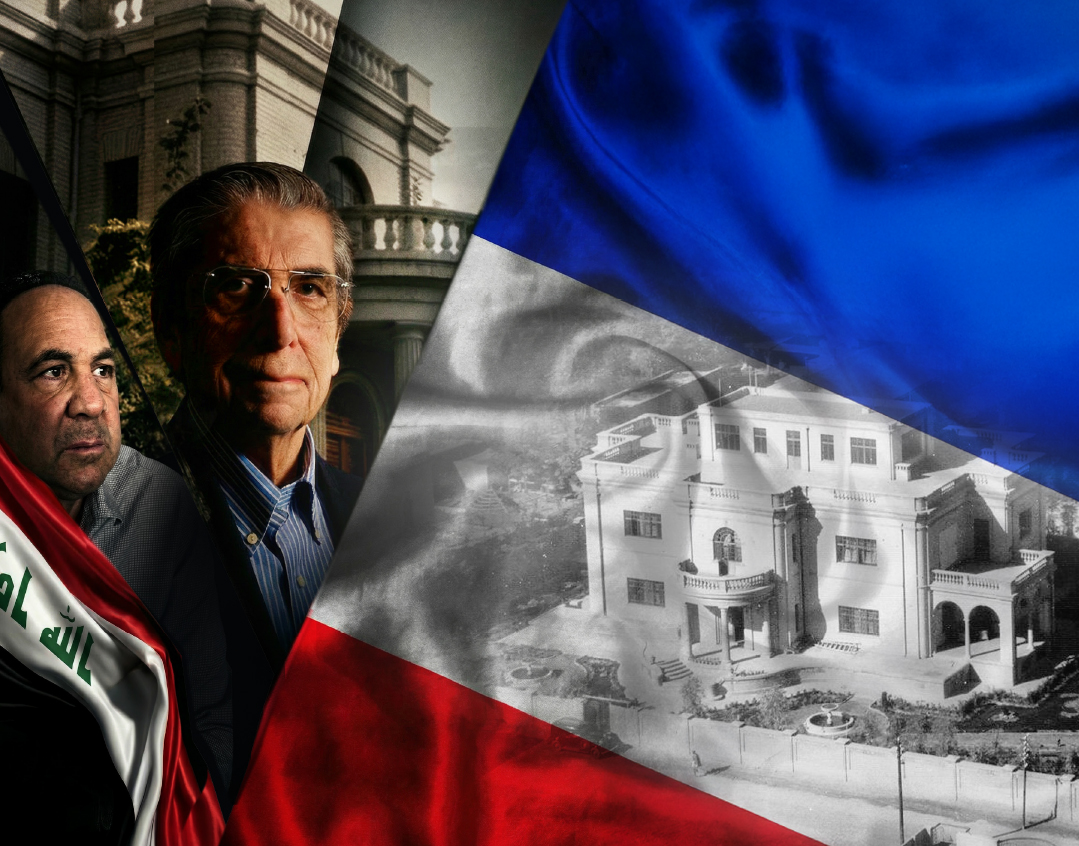

Photos: Shuki Lehrer, M. Goldstein, Mishpacha Archives

When the Vizhnitzer Rebbe shlita, Rav Yisrael Hager, agreed to take on the mantle of leadership in Vizhnitz, it was with one stipulation: the honorific “kvod kedushas” — the way a rebbe is usually addressed — would not be added to his title. Yet his extreme humility has not inhibited his massive following. In the short months since his appointment, he has emerged as a leader of note. As Reb Yankele of Pshevorsk predicted, long before anyone envisioned him at the helm of Vizhnitz, “Thousands of chassidim will yet flock to him”

4:55 a.m., Rechov Toras Chaim 4, Bnei Brak

It’s time for the changing of the guard in Bnei Brak’s Shikun Vizhnitz. The last of the nocturnal Torah scholars have gone to bed, and the first of the early risers have yet to leave their homes. At this predawn hour, not quite night but not yet day, the sound of an alarm clock echoes from the window at Toras Chaim 4. It isn’t just the night guard that’s changing; the regime has changed as well. Even before the sun set on the previous Rebbe, Rav Moshe Yehoshua Hager ztz”l, it began to dawn on his eldest son, Rav Yisrael, who lived with joy despite years of humiliation, and accepted Hashem’s decrees with love. Sure enough, the time came for Rav Yisrael Hager to receive the honor due him, just as Reb Yankele of Pshevorsk ztz”l predicted when Vizhnitz’s eventual successor was a shunned, exiled avreich: “Thousands of chassidim will yet flock to him.”

Rav Yisrael ben Rav Moshe Yehoshua has indeed become great — a modern-day David HaMelech, distanced from his own family, yet ultimately emerging as a king. Together with his brother, the Rebbe Rav Menachem Mendel, he is reigniting the glory of Vizhnitz after the chassidus endured nine years of darkness due to the previous Rebbe’s illness.

Rumor has it that in the new Vizhnitzer Rebbe’s home, there are six alarm clocks, each one set at half-hour intervals. The Rebbe makes sure never to sleep more than a half hour straight, so every half hour, the Rebbe gets up, walks around the house murmuring some holy words, and goes back to sleep until the next alarm rings. This has been his habit since he was a boy.

One street over, on Rechov Ahavas Shalom, an assortment of mourning notices, all of them black, half of them torn, remain as a mute reminder of the day in Adar when the previous Rebbe, Rav Moshe Yehoshua Hager — the Yeshuos Moshe — left his chassidim for the Next World. He lived at Number 15. The house on the left, Number 13, was the house of his father, the Imrei Chaim, who passed away 40 years ago.

The Rebbe shlita enters the building at Ahavas Shalom 15, to use the same mikveh his father used to purify himself. Before he succeeded his father, the Rebbe used to immerse himself at the private mikveh in the home of Rav Aharon Eliyahu Feldman, the son of Rav Chaim Moshe Feldman. Now, having moved into his father’s position, the Rebbe has permitted himself for the first time to make use of his father’s mikveh.

Immersion in a mikveh is an essential part of the Vizhnitzer avodah. The previous Rebbe would sometimes perform three immersions a day. During the shivah for his father, the current Rebbe observed the halachah prohibiting a mourner from immersion, but on Friday night, after the packed Maariv, he slipped quietly into his father’s mikveh before reciting the first Kiddush since the petirah.

5:20 a.m.

The early risers are already in the streets. Some even have the privilege of being blessed by their Rebbe to have a “good morning.”

5:25 a.m.

The Rebbe disappears into his home, where he will spend the coming hours ensconced in his private room with the thousands of seforim he has amassed over the past years with great effort and financial outlay, sometimes even skimping on his own food. The contents of these seforim, he has told his confidants, have always been a consolation to him at times of suffering.

At the first Seudah Shlishis after the Rebbe shlita’s coronation — with the lights off according to Vizhnitz tradition — the crowd held their breath as the Rebbe began to speak. “What is there for me to say?” he began tearfully. “How can I speak? My great, holy father has left us for his eternal rest, and we are left behind in sorrow.” The Rebbe began to sob unchecked tears, and then continued, “My holy ancestors, beginning with the Ahavas Shalom, led this congregation and they were worthy of it. The years of their youth were years of greatness. For me, unfortunately, it is not the same.

“It is very hard for me to be called the Rebbe. That is the way things are done; it is the way of the world, and I have no choice. But I ask that the accompanying title of kvod kedushas not be added at all, neither in private nor in public, for there is no truth to it.”

The Rebbe went on to declare that his task would be only to succeed his father and to bring the kvittlach that would be presented to him at the resting place of his forebears. Then Shabbos was over and the fluorescents went on, leaving over 5,000 men squinting in the light, watching as their new Rebbe hid his own face in his hands.

An elderly chassid, Reb Avraham Mordechai Malik, passed by and whispered to him, “You are my fourth Rebbe. I had a relationship with the Ahavas Yisrael, with the Imrei Chaim, with your father, the Yeshuos Moshe, and now with you. I do not accept your statement that you are not worthy.”

Over nine years have passed since the Yeshuos Moshe became ill. During that time Rav Yisrael Hager took it upon himself to serve as the leader of the flock until his father would recover, always believing and teaching others to hope that his father would lead the Chassidus until the coming of Mashiach. On that night when the lights went out at Ahavas Shalom 15 and all of Vizhnitz—and the Jewish world in general — was cast into mourning, the bereaved sons Rav Yisrael and Rav Menachem Mendel looked like men whose entire world had been destroyed — despite the Rebbe’s frailty, despite the ambulance that had been parked outside his home for years already, despite the knowledge that his end was near.

Yet the chassidim have embraced the new Rebbe. His leadership is founded on his exhaustive Torah study, his incredible humility, his tremendous value for the tiniest fragment of time, his joyous prayers, his broken heart, his striving for truth and perfection, his good middos, his love for his fellow Jews, and his incredible simplicity. These were his traits when he was simply an anonymous tzaddik serving Hashem in his own corner, and they remain his attributes now. For Rav Yisrael, there is no difference between the avodah of an outcast in the corner of an empty beis medrash and the holy avodah observed by tens of thousands of pairs of eyes.

New Beginnings

7 p.m., Rechov Ahavas Shalom 13

This is where the light of the Imrei Chaim came forth, and this is where the sun of Vizhnitz continued to shine under the leadership of the Yeshuos Moshe. This is where the previous Rebbes received kvittlach, and the present Rebbe is continuing that tradition.

Still, the title “Rebbe” is like a stab to his innate humility. When he first entered the beis medrash as Rebbe and found his shtender covered with a cloth on which was embroidered “lichvod kvod kedushas maran ha’admor shlita,” the Rebbe ordered the cover removed and gave instructions for it not to be returned until the offending title had been removed. The Rebbe also refuses the customary niggun and escort on the way to and from the beis medrash.

It’s been nearly a decade since kvittlach were accepted in Vizhnitz.Now Rav Yisrael sits in the room where his father and grandfather received supplicants, in the same position familiar to followers of the Imrei Chaim, accepting kvittlach from the multitude of visitors. At the front of the room, near the main door, is a large bookshelf where the seforim of the Imrei Chaim are kept. The volumes are very old and mostly moth-eaten. Their ink has faded, but their sanctity remains.

When the Shomrei Emunim Rebbe came here for nichum aveilim, he asserted that prayers offered in this room are more effective than those recited at the gravesite itself. “The nefesh is there, but the ruach is here,” the Rebbe said. This place is known as the prava shtiebel.

Outside sits the Rebbe’s new attendant, Rav Shaul Greenberger. Rav Greenberger was a rebbi in Yeshivas Vizhnitz until the Rebbe appointed him as his personal shamash who’d write the notes on behalf of thousands of visitors.

Once during the shivah, the Rebbe was brought a drink in a silver cup. To the surprise of the gabbaim, the Rebbe refused to accept the cup. “As long as my brother [Rav Menachem Mendel], the Admor shlita, is not served in a cup like this, I will not drink from it,” he whispered to the gabbai. An additional cup was brought, identical to the first, and only then did the Rebbe agree to drink from it.

During the shivah, the Rebbe equipped himself with a wad of twenty-shekel bills to distribute to the paupers who would visit. The gabbaim decided on the twenty-shekel strategy, hoping to prevent the Rebbe from giving out excessive amounts of money. The Rebbe, however, not one to be restrained in chesed, added 200 shekels from his own pocket to every twenty-shekel bill he dispensed.

Those who’d known him as a youngster weren’t surprised. Yisrael Hager was still a young avreich when he began following the precedent of his forebear, the Tzemach Tzaddik, who never kept a coin in his own possession and distributed limitless amounts of tzedakah. Such vast sums did he distribute that his great-grandson the Imrei Chaim was still paying off his debts in the period prior to World War II.

The older members of the Chassidus remember how, when Reb Yisrael was younger, anyone who came to him in financial distress was granted generous assistance, and if the Rebbe himself lacked funds, he would raise the money or borrow from others.

Yearnings of the Heart

Rav Yisrael Hager was born in Tel Aviv in Iyar 1945, a year after his father, the Yeshuos Moshe, arrived to the safety of Eretz Yisrael from the valley of death.

Vizhnitz, like most of the chassidishe courts, had been shattered by the Holocaust. Some had already predicted the end of the dynasty. They thought that Torah study and Chassidus had left the world along with the souls of the murdered Jews. The celebration of this first bris in Eretz Yisrael proved that all was not lost; the kingdom of Vizhnitz would continue.

The Imrei Chaim — Rav Chaim Meir Hager — had not yet arrived in Eretz Yisrael, so the Yeshuos Moshe honored his father’s brother, the Damesek Eliezer, with the position of sandak. The Damesek Eliezer passed the honor on to his own uncle, Reb Yisrael of Husyatin, the eldest tzaddik of Ruzhin, who lived in Tel Aviv at the time. Rav Baruch Rabinowitz of Munkacz served as the mohel.

Rav Yisrael’s childhood memories are inextricably intertwined with the venerated image of his recently departed father. He recalls his father’s packed daily schedule, his incredible hasmadah, his great care to guard his eyes from forbidden sights, and, in general, the spiritual life that he managed to live even under the conditions that prevailed in Tel Aviv at the time. The Rebbe shlita recounts these memories often, to transmit them to the young chassidim. He remembers how his father would take him to his Tel Aviv cheder with his eyes closed. After a short time, Rav Moshe Yehoshua removed his young son from the school and instead selected private tutors for him.

When Rav Yisrael was six years old, Yeshivas Vizhnitz moved from Tel Aviv to the new Vizhnitzer neighborhood under construction in Bnei Brak. Reb Moshe Yehoshua continued to disseminate Torah in Tel Aviv, taking little Yisrael with him every morning. The bus driver always reserved the two front seats for them, for reasons of modesty and kedushah.

In 1963, Rav Yisrael became engaged to the daughter of the Chernobyler Rebbe ztz”l. At the engagement celebration, the Chernobyler Rebbe asked the chassan’s grandfather, the Imrei Chaim, what gift he was giving to the chassan. The Imrei Chaim replied that he was giving young Yisrael a famous letter written to the Ahavas Shalom, the founder of the Vizhnitz dynasty, by Rav Velvel miTscharan-Ostra. Rav Velvel, before departing Europe for Eretz Yisrael, had advised his chassidim to visit the Ahavas Shalom in his stead. He later penned a letter promising that the Ahavas Shalom’s sovereignty over the Chassidus would remain in his family forever. By presenting the young chassan with the letter, the Imrei Chaim made it clear that he considered his young grandson to be the next link in the family chain. Almost 50 years have passed since then, entire worlds have been destroyed and built, and the Imrei Chaim’s prophetic promise has been fulfilled. His grandson, the then-chassan, has become the next link in the chain of the Vizhnitzer dynasty.

As an avreich, Rav Yisrael received rabbinical ordination from Rav Moshe Aryeh Freund ztz”l, the gaavad of Yerushalayim, and Rav Yehoshua Mendel Ehrenberg ztz”l of Tel Aviv, in addition to other well-known rabbanim. He was already giving shiurim in Yeshivas Vizhnitz when he began to serve in rabbanus after the Imrei Chaim’s passing on the 9th of Nissan, 1972. His father, the Yeshuos Moshe, then ascended to the position of Rebbe. Rav Yisrael’s position was established when, during the shivah for the Imrei Chaim, both the chassidim and local rabbanim came to him to sell their chometz. Among them was the Steipler Gaon ztz”l, who until then had always come to the Yeshuos Moshe to sell his chometz.

The previous Rebbe, the Yeshuos Moshe, often expressed love and admiration for his son, the current Rebbe. He would quote the words of Chazal, “Yisrael alah b’machshavah l’fanav,” to allude to the fact that his own son Yisrael was constantly in his thoughts. Once, a chassid was in the Imrei Chaim’s room with a note in his hand when Rav Yisrael, who was then a young boy, entered the room to borrow a sefer. The Imrei Chaim directed a loving gaze at his grandson and remarked to the other man, “This grandson of mine has three attributes of greatness. He has a broken heart, but his heart is large enough to have room for his own burdens and those of every Jew, and his soul is pure and free of stains.”

The Yeshuos Moshe once told his chassidim, “You should know that my son, Rav Yisrael, has feared sin since his youth. He is named after my grandfather, the Ahavas Yisrael, who shared that same trait.”

When the Imrei Chaim passed away, his beloved grandson was 28 years old. Rav Yisrael’s years with the Imrei Chaim left an indelible imprint on him — for the Imrei Chaim loved him like his own son. “I know all of them,” his aunt, Rebbetzin Tzipporah Friedman, the sister of the Yeshuos Moshe, remarked. “The eldest son was on a high level since he was small. As an avreich, he reminded us of our grandfather.”

Secret Meetings

From the time he was a young man, Rav Yisrael cultivated strong connections with his uncles, Reb Yudale of Dzhikov ztz”l and the Vizhnitzer Rebbe of Monsey shlita. The Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe says that his nephew possesses the power of prayer and the power to dispense blessings, and he has encouraged him to accept kvittlach. Rav Yisrael also maintains strong connections with the elderly admorim of Tosh and Skulen.

Just two weeks ago, Rav Shmuel Wosner of Bnei Brak expressed his approval of a relative’s decision to daven Minchah in Rav Yisrael’s minyan, saying, “to him, it’s worthwhile to go, for he is a chashuveh Yid.”

The Rebbe also has a strong connection to Rav Aharon Leib Steinman shlita, who calls him “the tzaddik of Bnei Brak.”

But the most notable of Rav Yisrael’s relationships was the mysterious close connection he formed with the Lubavicher Rebbe ztz”l. Rav Yisrael was the only individual granted a private audience at the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s home on President Street during the period when the Rebbe had ceased holding private audiences, when the only direct contact he had with the public was the distribution of dollar bills on Sundays. Their conversation was long and shrouded in secrecy, and until today Rav Yisrael refuses to divulge the details of that meeting. Just two weeks ago, Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky visited Rav Yisrael and mentioned that he’d also been present at that rare meeting. Behind closed doors, he recounted, the Lubavitcher Rebbe had blessed Rav Yisrael “l’maan yaarich yamim al mamlachto,” an enigmatic blessing at the time. When Rav Yisrael left the room, the Rebbe told his inner circle, “Keep an eye on this one,” implying that he’d have a distinguished future.

Rav Yisrael still makes public note of the date of the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s passing, 3 Tammuz, and he often leads his chassidim in Chabad niggunim. It seemed only fitting, then, that Rabbi Leibel Groner flew in to Bnei Brak to perform nichum aveilim when Rav Yisrael was sitting shivah for the previous rebbe.

The Rebbe shlita also maintained a relationship with Rav Yankele of Pshevorsk in Antwerp, who remarked about him, “You will yet see thousands of people crowding in the shade of the Vizhnitzer Rebbe’s son and flocking to receive brachos from his mouth.” Reb Yankele uttered these words during the time of Rav Yisrael’s banishment; at the time, it seemed like nothing more than a far-off fantasy.

His son Reb Leibish, the current Rebbe of Pshevorsk, was visited by a British Jew stricken with a deadly disease. Reb Leibish told him to appeal to the new Vizhnitzer Rebbe, since he is a “poel yeshuos.”

The Sweet Years

For 18 years, from 1984 until 2002, Rav Yisrael Hager privately mourned an event that no one understood, something that no one could even question. Inexplicably, he’d been banished from his father’s court. Rav Yisrael accepted the decree in silence, serving Hashem in his own corner, in solitude.

For nearly two decades, the distanced son waited for a message that his father had summoned him to return. The chassidim understood that the entire matter was beyond their comprehension. Rav Yisrael himself warned them not to become involved in the affair, for it would be playing with a dangerous fire. He calls those years “the sweet years,” for it was then that his soul was purified in the crucible of suffering.

A chassid relates: “Around 1995, Rav Yisrael went alone every day to visit the burial place of his beloved grandfather, the Imrei Chaim, Rav Chaim Meir Hager. There was a Yemenite guard at the Vizhnitz cemetery in those days, and he related that he would see the Vizhnitzer Rebbe’s oldest son spending hours at the grave in tearful supplication.”

During those years, Rav Yisrael wrote dozens of letters to the Vizhnitzer Rebbe, expressing an outpouring of love from a son to a father. One year, the Rebbe broke the silence and called his son to wish him mazel tov on his birthday. At the end of the conversation, the Rebbe wished his son many long, healthy years. Rav Yisrael responded, “With you, Father, we will have happiness together.”

“Amen,” said the Yeshuos Moshe, and Rav Yisrael’s joy knew no bounds.

“During his most trying periods, we did not see him broken,” one of his disciples relates. “There were times when he would cry, but he never despaired.

“At the wedding of his son Reb Yitzchak Yeshaya, a small reception was held at his beis medrash on Rechov Rashi,” the chassid continues. “His sister, the Belzer Rebbetzin, came to join in the festivities. The Belzer Rebbetzin always remained close to him. In the middle of the simchah, the Rebbetzin approached her brother, wished him mazel tov, and burst into tears over his forced isolation. No one who was present could refrain from weeping along with her — except for one person. We looked at the Rebbe’s face, and we saw that not a muscle was moving. He thanked the Rebbetzin and told her, ‘We should meet at simchahs.’ And with that, the discussion ended.”

During those years, Reb Yisrael made frequent trips abroad in order to provide for his family. When he returned and his children asked him if he was successful, he would invariably say, “Baruch Hashem, I was matzliach.” But they often learned afterward that that particular trip had ended in bitter disappointment.

“I’ll Never Be a Rebbe”

It was the week before Purim in 2000. Rav Yisrael was returning to Bnei Brak from the forsphiel — the pre-wedding celebration — of the children of the Toldos Aharon and Tosher Rebbes. It began to rain, making the Jerusalem–Tel Aviv highway slick and perilous, when a 17-year-old driver rammed into the car in which Rav Yisrael and his son were traveling. Rav Yisrael was severely injured; three of his ribs were broken, and he was a hairsbreadth away from suffering irreversible lung damage.

Soon Rav Yisrael’s condition took a turn for the worse; in Vizhnitz, everyone shuddered when they learned about the accident. His father, the Yeshuos Moshe — who had not seen him in 16 years — cried bitterly as he recited Tehillim. Later, he went to pay his son a visit.

When the Yeshuos Moshe entered the ICU at Hadassah, he asked that no one else be present when he came to see his son.

Rav Yisrael’s excitement knew no bounds. His ability to speak was limited, since he was hooked up to an array of medical machinery. But he straightened up slightly, out of respect for his father, looked at him longingly, and murmured a single sentence that would be remembered forever — “See my poverty and my toil.” In those words, he encapsulated the depths of his anguish. The Yeshuos Moshe cried with him.

Rav Yisrael returned home for Purim, yet he was still immobilized. On Purim afternoon, his chassidim brought in a keyboard and an amplifier to liven up the seudah, placing the amplifier on a high shelf. Rav Yisrael was sitting in a special chair with his feet up, directly underneath, when someone tripped over the cord as the heavy amplifier fell directly onto his injured leg. His son, Reb Yitzchak Yeshaya, who had also been injured in the accident, was sitting in a wheelchair beside the Rebbe with a wounded pelvic bone. As the amplifier came crashing down, he looked on in shock and horror.

“We looked at the Rebbe’s face, but we didn’t see the slightest flinch. Not a muscle moved, not a sound was heard. This was a man whose intellect reigns over his emotions with absolute power,” one of his talmidim reported.

Reb Nechemiah Zaideh, one of the elder chassidim, is a master of the Torah of Vizhnitz. He recently told the young chassidim that such levels of emunah, bitachon, and good middos were rare even in previous generations.

“The Rebbe always conducts himself in the same manner regardless of the circumstances,” he says of the Rebbe shlita’s extreme personal discipline even in the face of pain and tragedy. “Whether he is in the presence of a tiny minyan or surrounded by thousands of admirers, he serves Hashem exactly the same way. No one can detect the slightest deviation.”

People often asked Rav Yisrael why he did not despair of receiving Divine mercy. After so much time had passed, and his personal redemption still had not come, perhaps it was time to establish a clearer future for himself? Rav Yisrael replied, “Every night as I lie in bed, my heart cries bitterly that the words of David HaMelech — ‘At night I go to sleep weeping, but in the morning there is song’ — should be fulfilled for me.”

Those close to Rav Yisrael Hager say that despair is just not in his lexicon. It never has been. In 1972, Rav Yisrael traveled to Meron to daven for the refuah of the Imrei Chaim. But when he got a message that the situation was critical, he detoured to Assuta Hospital to be with his beloved grandfather in his last minutes.

“When the Rebbe arrived at Assuta, he saw that no one was saying Tehillim,” reports an elder chassid who was with him that day. “They were all standing around and crying, because they knew that there were only a few hours left. Rav Yisrael stood in the corridor and began to shout, ‘Why aren’t you saying Tehillim?’ People looked at him in disbelief; the Imrei Chaim was close to death already.

“But he had no concept of despair. He was always hopeful, believing and trusting in Hashem. He’s had this intense emunah since he was a child. Even when his father’s health had so declined in the last years, it was impossible to discuss with him what would happen after 120.”

A chassid who remained close to Rav Yisrael during his years of isolation remembers one Hoshana Rabbah. “After the beating of the aravos, a few of his loyal chassidim grabbed pieces of the loose aravos that fell. After davening, Rav Yisrael asked them, ‘Why did you grab that from me?’ They said, ‘It’s a segulah for protection.’

“The Rebbe said, ‘I know that it’s a segulah for protection, but every person has to take his own aravah.’

“I said to him, ‘But the Rav is a gutter Yid [a chassidish expression for a rebbe].’ The Rebbe replied, ‘I am not a gutter Yid. I will never be a rebbe, and my father will bring us toward Mashiach.’

9 p.m., the Imrei Chaim’s waiting room

There is a brief recess in the kabbalas kahal, which will continue past midnight. The Rebbe wishes to daven Maariv. A large crowd pushes its way inside; the people want to daven together with their Rebbe. A small number of chassidim actually succeed.

The Rebbe washes his hands and moves toward his shtender with measured steps. The chassidim relate that since he assumed the mantle of leadership, even his movements have changed. They have become more regal — “rebbishe movements,” as the chassidim say.

The Rebbe begins Kaddish. The white cloth covers his shtender; the honorific has been removed per his request, while the donor’s name remains so the Rebbe can mention him in his prayers.

After davening has concluded, the Rebbe quickly returns to the prava shtiebel. Sixty scheduled visitors have yet to enter his chamber. Among them are newly minted chassanim celebrating their engagements tonight, three-year-old boys on the occasion of their first haircuts, and bar mitzvah boys. Much has changed, but the Rebbe’s rule for his chassidim still stands: Even from across the ocean, even at the most inconvenient time — “If someone needs me urgently, Heaven forbid that I should turn him away.”

1 a.m., the Imrei Chaim’s waiting room

Midnight has long passed, and about 20 men are still waiting to see the Rebbe. The Rebbe won’t leave until all 60 of the people scheduled to present kvittlach tonight have left their burdens of troubles behind in this room.

This is the man who would make his way to a mental institution every week, to sing and dance with a tortured bochur.

This is the man who comforted a young Vizhnitzer chassid whose newborn baby required surgery in New York to correct a serious health issue. “I have no money, no passport, I’m barely 20 years old,” the distraught father had cried. The Rebbe asked Eli Yishai to expedite the passports, Meir Porush the visas, Yaakov Litzman the financing from the health fund — and then told the young man, “Make sure to come say goodbye before you leave.” His goodbye present: several thousand dollars’ pocket money, to help the frightened young couple navigate a foreign country.

This is the man who phoned a Satmar activist in London, offering to help raise money for a Jewish couple facing a prison sentence. To the activist’s questions of “Do you know him? Do you know the family?” he answered “No, I just know that they’re Yidden and they need help.”

This is the man who hoped and believed throughout years of loneliness, who understands the pain and suffering of the thousands who now see him as their leader.

The clock now strikes 2 a.m. Soon the last visitor will leave, and the Rebbe will return to his home, where he will conduct conversations with his chassidim in America until three o’clock, snatch a few half-hour intervals, and then be up again at five.

In Vizhnitz today, there is time for it all.

Utter Simplicity

Rav Yisrael Hager, heir to the Vizhnitz dynasty, always refused the trappings of pomp. For years he traveled in an old-model Citroën — instructing his gabbai that anyone needing a ride should be picked up. One of the chassidim finally told him it was time for a new car, more appropriate for his status. Rav Yisrael couldn’t understand why.

“It’s not a nice car,” the chassid explained.

“Nu, so put flowers on it,” Rav Yisrael replied.

The situation remained that way until the car died. At that point, he allowed a new car to be purchased, but with two stipulations: it had to be secondhand, and it could not be a German make.

“The concept of simplicity takes on a new dimension when you are with him,” says one chassid. “I used to go to him for Shabbos meals. If I asked a bochur next to me to pass me a drink, the Rebbe would look hurt and say, ‘Why don’t you ask me?’$$$SEPARATE QUOTES$$$”

“Throughout his life, the Rebbe has fought any trappings of honor,” another chassid relates. “One Lag B’Omer, I met him in Meron. I watched him dance in the courtyard of the tziyun, and when someone placed his hand on the Rebbe’s shoulder, I couldn’t tolerate the affront and told the dancer to remove his hand. The Rebbe heard and reproached me: ‘I want to dance with Jews! If you can’t accept that, then go somewhere else.’

“He hated anyone making a fuss over him, and would go to any length to avoid it. At the Shabbos sheva brachos of one of his sons, the chassan’s friends tried to escort the future Rebbe to his home, but he insisted that they leave him alone. A few of them persisted in following him anyway, until he slipped into a building. The bochurim thought he would emerge shortly, but he actually left the building through a back entrance and climbed over a fence to get back to the street, in order to make his way home by himself, without an escort.”

When Rav Yisrael visited the Catskills, he was hosted by a family of Bobover chassidim. One summer his hosts were blessed with a new grandchild. He watched them planning a trip to the city, noting their indecision and correctly surmising that they weren’t comfortable leaving their teenaged son in the mountains by himself. “Don’t worry,” he offered, “leave him here, I’ll babysit.”

That night the boy fell asleep on the couch. Rav Yisrael gently awakened him at 8:15 the next morning so he wouldn’t miss the zman Kriyas Shema, even bringing the fifteen-year-old water for negel vasser.

Two years ago, a Vizhnitzer bochur who had completely abandoned Yiddishkeit and his family heard a knock on the door of his lonely lodgings. To his shock, Rav Yisrael was standing there. “I hear you’re all alone,” he said with warmth and concern, “and I wanted to make sure you have some money in your pocket.”

“I had been sure no one was thinking about me anymore,” the boy told his illustrious visitor. “But since you care, I’m going to put on my tefillin” — gesturing toward a dusty bag packed high on a shelf. That visit set the youngster on a slow but steady path back to observance.

The Vizhnitzer Dynasty

Rav Yaakov Koppel Chassid, the baal tefillah of the Baal Shem Tov

Rav Menachem Mendel Hager of Kosov, the Ahavas Shalom

Rav Chaim Hager of Kosov, the Toras Chaim

Rav Menachem Mendel Hager of Vizhnitz (1830–1884), the Tzemach Tzaddik

Rav Boruch Hager of Vizhnitz (1845–1892), the Imrei Boruch

Rav Yisrael Hager of Vizhnitz (1860–1936), the Ahavas Yisrael

Rav Chaim Meir Hager of Vizhnitz (1888–1972), the Imrei Chaim

Rav Moshe Yehoshua Hager of Vizhnitz (1916–2012), the Yeshuos Moshe

Rav Yisrael Hager shlita, the current Vizhitzer Rebbe

The Rebbe Rav Menachem Mendel Hager of Vizhnitz shlita

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 410)

Oops! We could not locate your form.