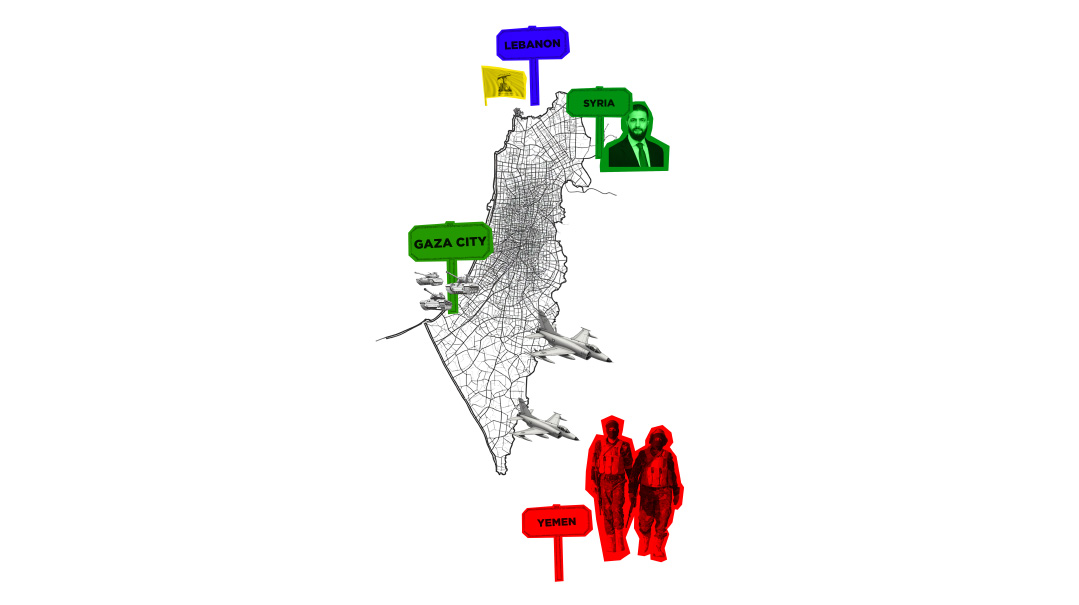

Russian Roulette over Syria?

Photos: AFP/IMAGEBANK

I

t’s semi-official: the war in Syria is over.

Though Bashar al-Assad’s army hasn’t rooted out all remaining vestiges of resistance, its victory last week in the southern Daraa district, where rebels first launched the rebellion in 2011, means that Assad, Russia, and Iran have won.

In the last year and a half, rebel enclaves throughout the country have been methodically vanquished, as Russian officers have brokered agreements for towns and villages to relinquish their heavy weapons and swear allegiance to the Assad regime.

Still under rebel control is the vast Idlib region in the north, as well as a pocket in the Syrian Golan. The Kurds are still in the east, but Assad has regained all the major cities there, granting him geographical contiguity from the Mediterranean coast in the north to the Jordanian border in the south.

If the agreements in the Daraa district continue to hold, the regime is expected to aim for similar treaties with the local militias still exerting control in the Syrian Golan, some of which, according to foreign reports, have developed friendly ties with Israel in recent years. Israel likewise has an interest in seeing Assad’s entry into the area pass without bloodshed.

That leads Israel to the next stage, which will see Assad’s forces reoccupying positions it took before the outbreak of the civil war. It’s important to note that according to Israeli intelligence, Russia’s commitment to Jordan and Israel, which was supposed to prevent Iranian forces and Hezbollah from taking part in the fighting in Daraa, was not carried out in full. While the majority of the forces in the district are Syrian and Russian, some Hezbollah fighters and Iranian officers have been observed.

Russia’s endgame for its Syrian intervention includes establishing a new government in Damascus, instituting a constitution (which Moscow has already formulated together with Assad) and holding elections. To reach that point, in addition to placing forces in the Golan Heights, Russia will also have to persuade Turkey to withdraw its forces from northern Syria, which it invaded as part of its battle against Kurdish factions.

In his summit with President Trump in Helsinki next week, Russian president Vladimir Putin will also attempt to equate the withdrawal of American troops — some of whom are in northern Syria and some at the Al-Tanf base at the juncture of the Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi borders — with the withdrawal of Iranian forces. At the moment, the chances of that happening seem negligible. If Iran’s own declarations are anything to go by, Tehran has no intention of leaving Syria. Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov backed that stance last week, stating that it would be unrealistic to expect a full withdrawal of Iranian forces, which contradicted previous declarations by Putin.

One of the biggest questions is whether Putin might propose linking the withdrawal of Iranian forces from Syria with the Iranian nuclear agreement. That is, offering the Iranians a chance at new negotiations and delaying the onset of new sanctions in exchange for a full withdrawal from Syria. Such an eventuality could put Israel in a precarious position, forced to choose between the devil and the deep blue sea: a valid nuclear agreement that Iran will fulfill to the letter, but which leaves it free to pursue the bomb as soon as the deal expires — or continued Iranian presence in Syria.

In another week, Israel is liable to wake up to a new Russian-American agreement, and a reevaluation of its strategy.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 718)

Oops! We could not locate your form.