Queen of Hearts

Being in aveilus can be transforming. Life goes barreling on, demanding its due, like a hungry child. Babies are born, engagements take place, weddings are celebrated, seasons pass, colors and fashions change and beckon as music plays in the background. But the mourner, who doesn’t attend simchahs, doesn’t listen to music, doesn’t buy new clothing, walks beside life — there, but slightly distant.

Death of a loved one takes you out of life and puts you into observer mode. Thousands of days and millions of minutes begin to coalesce, in your mind, into a life story. It is death that gathers up all the plot twists, curve balls, and bolts from the blue that life hands us and pulls them together into a theme, with a title. Because if there is an end, there was also a beginning. Death is the ending that bundles seismic life events with all those small moments — the cups of coffee, the loads of laundry, the oh-my-it’s-summer-again fleeting thoughts — and frames them into one cohesive whole, called life.

The end of my mother’s life — as sad and painful as it was — was also beautiful.

It was Motzaei Shabbos in Eretz Yisrael, but still Shabbos in America when my sister and I got the dreaded phone call to come, because the end was near. As recently as Thursday night, which was Motzaei Purim, we had spoken to my mother on Skype. Though uncomfortable, she had been so alive, smiling her beautiful smile — and giving her trademark wince at the off-key singing of some of the besodden seudah participants.

My sister and I wrangled our way onto an El Al flight leaving at midnight, communicating with my brother through the non-Jewish aide, hoping against hope that we would still get there in time to say goodbye.

Our frantic phone call upon landing assured us that Mommy was still alive, although no longer conscious. We wound our way through the endless, endless lines of passport control in New York with a slow, draggy, moving-under water sensation, feeling like a cliché come to life, trying to get to the head of the line by telling the officers that our mother was dying.

Oh, the wonderful gift of technology that allowed us to connect to the hospital room during the tortuously long hour-and-a-half drive from the airport. From the backseat of the taxi we tuned into the charged but strangely peaceful atmosphere around my mother’s bed. We could hear the beep-beep of the machines, see the rise and fall of my mother’s breathing; we could see my father sitting at the foot of her bed, eyes glued to her face, and all her children and many grandchildren around her.

We talked to my mother. Mommy, please wait, we’re on our way. Don’t leave before we get there. Vidui had been said and re-said, and the family began to sing. Beautiful, fitting songs. “Ki B’simchah Tzeitzayu”. “V’taher Libeinu.” We watched, choked with sobs, willing the taxi to go faster.

As we swerved into the hospital driveway, two of our nephews were waiting downstairs for us. “Run,” they said, pulling the car doors open. “Leave the suitcases.” We dashed in, teetered for a few seconds gaining our bearing, then ran for the elevator. Yet death was faster. As the elevator slowly inched its way upward, my mother, Pessa bas Rav Chaim Hakohein, may she rest in peace, moved from This World to the Next.

We didn’t make it for the yetzias haneshamah, but we were there to see my mother’s face, so beautiful and so, so peaceful. We were there to cry together and to watch my father lean over and whisper in my mother’s ear, to hear his thanks to her and his blessing to her on her journey. We were there to hug and hold the life in the room, which was teeming with my mother’s progeny, both biological and spiritual. We were there to feel the strength of her legacy. My mother was no longer there — but in this imperfect world, there was life.

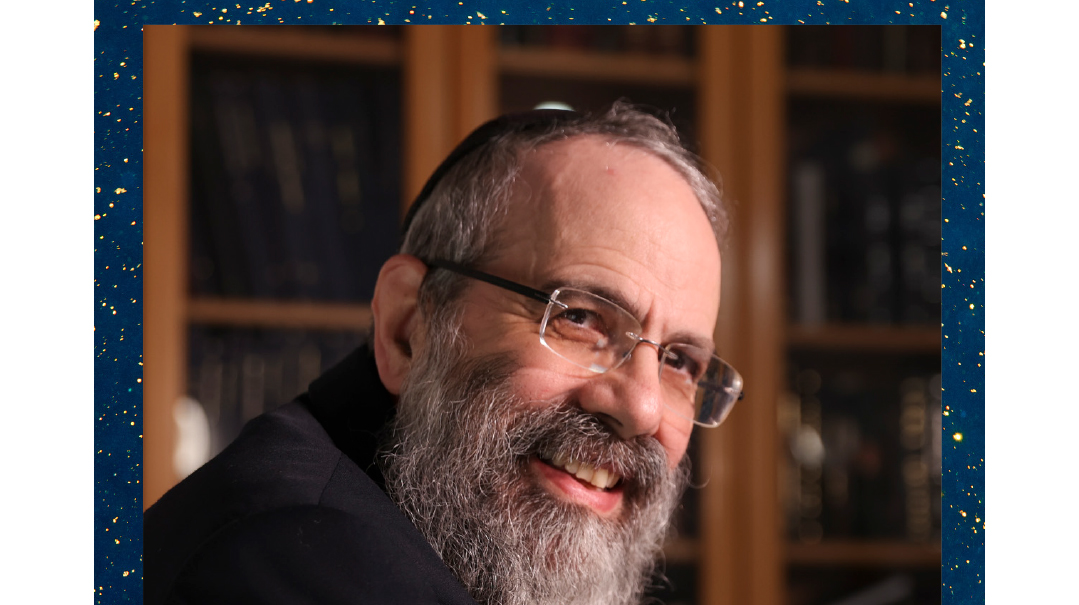

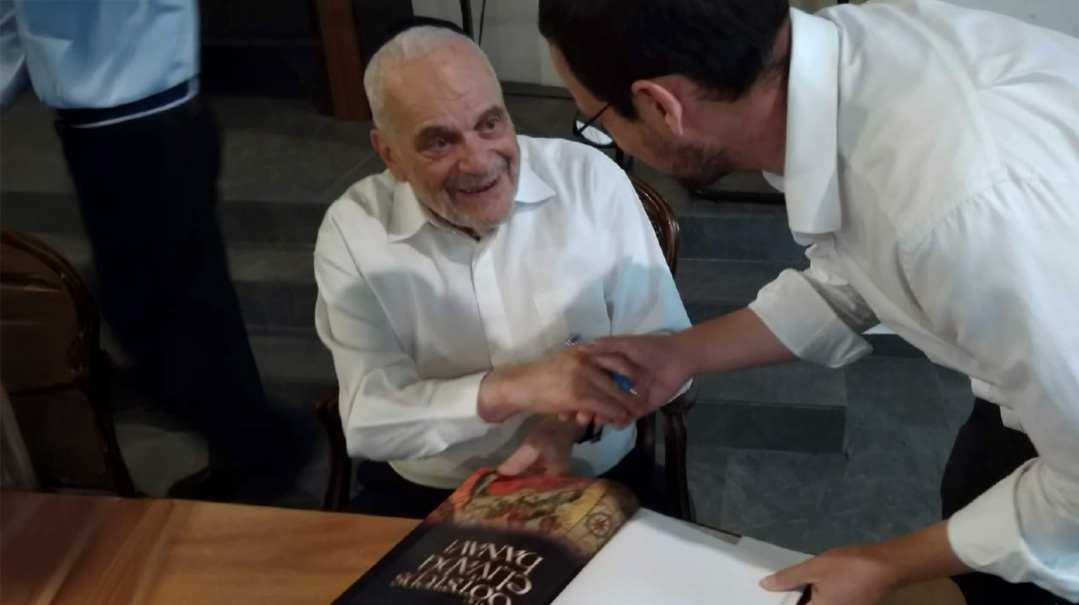

My mother, Mrs. Paula Eisemann, was born in Berlin, Germany, the daughter of Rabbi Chaim Cohn, rav of a shul in Berlin, and the first Torah teacher of Rav Shlomo Wolbe, z”tl. In a sefer dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Rav Wolbe, zt”l, calls him Mori v’rabi hamuvhak, hachassid shebekehunah.

The morning after Kristallnacht, my grandfather took his young children to the site of his burned-to-the-ground shul, and told his family never to forget what they saw. Wondrously, the next morning, the family — two parents, seven children, and a grandmother, were able to make their way out of Germany to Switzerland, and from there to London.

My mother’s father was a tall, handsome man with a long beard who loved life with exuberance. My mother used to tell us how her father would spread his arms wide and flap them as he ran down hills, just for the fun of it. Her father’s teasing suggestion when she cringed with embarrassment — “Just pretend that we’re only distantly related”— became a well-worn family joke.

Through a series of serendipitous events, the family was able to procure a house in a small seaside town called Dorking, where they opened up a boarding house to make ends meet — though perhaps “boarding house” isn’t the right term for a place in which indigents stayed for weeks and even years on end, becoming members of the household.

Shortly after they arrived in England, my grandfather was exiled to the Isle of Man as a precaution, lest he was a German spy(!). He was taken away right before his son’s bar mitzvah and was gone for about a year. Brokenhearted that his father had missed hearing him lein, my uncle prepared the parshah every week thereafter, in the hope that his father would be released and becoming a skilled baal korei in the process.

Oops! We could not locate your form.