Shackled, but Not Silenced

| February 17, 2026They tried to silence him, but José Daniel Ferrer never lost his voice

Photos: AP images, personal archives

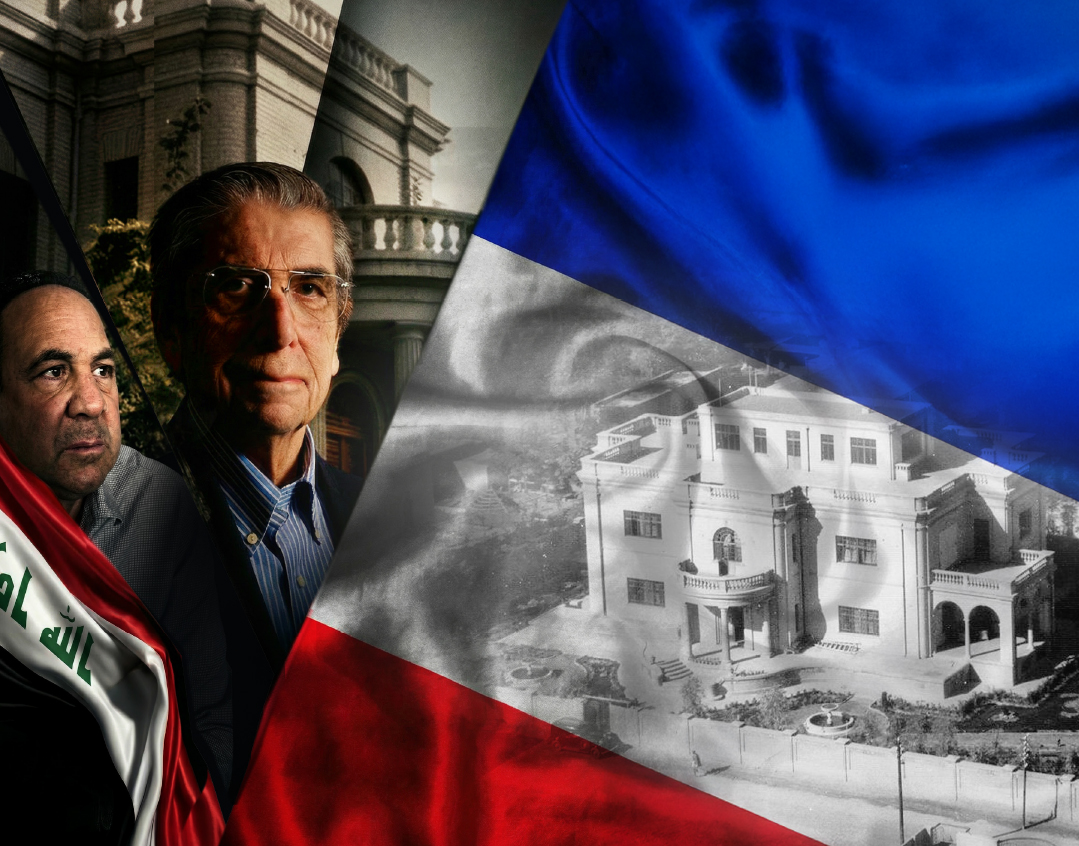

José Daniel Ferrer, leader of Cuba’s most vocal pro-democracy opposition faction, spent years behind bars on cooked-up charges so that the regime could remove him from the street and silence him for good.

Today, from his new home in Miami, he speaks about the torture, the horrible prison conditions, and the regime’s darkest secrets. An exclusive interview from a safer haven

Sunset fell over Palmarito de Cauto, a fading town in eastern Cuba’s Santiago province.

The long, dusty street slipped into darkness — except for a single light glowing in the last house on the corner.

Inside, José Daniel Ferrer sat at a makeshift desk stacked with pamphlets, handwritten complaints, and lists of those arrested. Through the window, he could see the familiar symbols of power: a fading portrait of Fidel Castro mounted along the main road, the Cuban flag stirring lazily in the Caribbean breeze beside it.

Yet something about the silence that night felt off.

At 12:15 a.m., the street filled with the sound of engines. Soldiers fanned out, sealing off both ends. Boots thundered against concrete. The door exploded inward.

One rifle was aimed at his head. Another at his chest. Ferrer knew this minute would come at some point, as he closed his eyes and waited for the shot.

Instead came the cold snap of metal cuffs biting his wrists. He was dragged into the darkness — still alive, but about to be swallowed into the unknown.

For more than two decades, Ferrer — founder of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU) — has been one of the Cuban regime’s most visible and unyielding opponents. He has been arrested repeatedly, sentenced to decades behind bars, beaten, isolated, starved, and, he alleges, deliberately poisoned.

A hundred days ago, gaunt and weakened, he arrived in the United States after what he describes as the harshest imprisonment of his life. In an exclusive conversation with Mishpacha, he recounts his struggle against the Castros — both Fidel and his brother and successor Raúl — and current president Miguel Díaz-Canel, and the price he paid for fighting against the machinery of repression that he says still grips the island.

R

esistance to communism in Cuba didn’t begin with hashtags or cell phone videos. It began in the mountains — and in blood — and has taken on various forms since Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution back in 1959.

In the years immediately following the revolution, armed bands of anti-communist fighters — known as alzados — retreated into the rugged Escambray Mountains, where for several years they waged a guerrilla war against the new regime in what Havana dismissed as the “Struggle Against Bandits,” but what historians now recognize as a full-scale rural insurgency. The rebellion was ultimately crushed with overwhelming military force, mass arrests, and executions.

Two years after the revolution, another dramatic attempt to unseat the regime unfolded on the beaches of southern Cuba. In April 1961, a CIA-backed force of Cuban exiles launched the ill-fated Bay of Pigs Invasion. The invasion collapsed within days, handing Fidel Castro a propaganda victory that tightened his grip on the island that’s just 90 miles south of Florida, and cemented Cuba’s alliance with the Soviet bloc.

From that point forward, resistance largely moved underground.

Over the decades, dissent assumed quieter but no less dangerous forms: underground pamphlets, clandestine human rights groups, hunger strikes, and fragile opposition movements constantly infiltrated by state security. The regime perfected a system of repression built on surveillance, informants, arbitrary detention, and long prison sentences. Political prisoners became a permanent feature of Cuban life.

Then, in July 2021, something unprecedented happened.

On July 11, spontaneous protests erupted across Cuba — from San Antonio de los Baños to Santiago. Thousands poured into the streets chanting “libertad” and “patria y vida,” openly defying the government for the first time in a generation. The demonstrations were driven by grinding shortages of food and medicine, extended Covid lockdowns, rolling blackouts, and an economy in free fall. It was the largest anti-government protest movement since 1959.

The response, though, was swift and severe. Security forces and plainclothes agents flooded the streets. Thousands were detained. Hundreds received lengthy prison sentences after truncated show trials. Human rights organizations described systematic beatings, coerced confessions, and closed-door proceedings.

And the unrest did not end there.

Through 2024, 2025, and into the beginning of 2026, protests have continued in waves — often erupting during prolonged blackouts that plunge entire neighborhoods into darkness. In the capital Havana and in other cities, residents have staged cacerolazos, banging pots and pans from balconies in acts of collective defiance. What began as isolated outbursts has hardened into a pattern of recurring public dissent.

As of February 2026, Cuba is now facing its most severe economic crisis in decades. Inflation has soared, food lines stretch for blocks, and fuel shortages regularly paralyze transportation. The island’s once-prized nationalized health system struggles with medicine shortages. Entire regions endure daily power cuts. Emigration has reached record levels (Cuba abolished its requirement for an exit permit in 2013, although the process is still heavily bureaucratic and expensive), hollowing out the country’s professional workforce and youth population.

It is into this long arc of resistance — from mountain guerrillas to pot-banging street protesters — that José Daniel Ferrer gained his hero status.

As a former political prisoner and founder of the UNPACU, Daniel Ferrer became one of the most recognizable faces of organized opposition in the post-Castro era. Arrested repeatedly, subjected to beatings and isolation, and held in harsh prison conditions, he represents a modern incarnation of Cuba’s dissident tradition: nonviolent, public, and unafraid to speak openly against one-party rule.

His recent arrival in the United States is not merely a personal milestone. It is the latest chapter in the story of a regime determined to silence dissent, and of individuals who’ve refused to be silenced.

While Ferrer has never been to Israel and has never expressed his opinion about the politically embattled Jewish state, he did say that he, together with dissident colleagues from other oppressive regimes, view Israel as the ultimate democratic experiment, a country refusing to be cowed by its surrounding totalitarian regimes and dictatorships.

Disappearing Dissent

Fidel Castro, Ferrer explains unapologetically, was a cunning and ruthless dictator. “He promised democracy and prosperity. Instead, he built one of the cruelest regimes in the Americas.”

Ferrer argues that deception lay even at the revolution’s core. He points to the 1953 assault on the Moncada Barracks — the failed uprising that launched Castro’s national prominence.

“He gathered supporters without revealing his true ideology,” Ferrer says. “Only after loyalty was secured did he move toward full communism.”

After the 1959 revolution, dissent was crushed with remarkable speed. Rural insurgents in the Escambray Mountains were hunted down. Independent newspapers were closed down. Political opponents were jailed or executed. Ferrer cites the 1994 sinking of the “13 de Marzo” tugboat, in which 37 people — including children — drowned while attempting to flee the island.

“It was a warning,” Ferrer says. “Leave, and you might die. Protest, and you will surely suffer.”

Economically, he claims, the revolution hollowed out a once-prosperous nation. Cuba, once among Latin America’s wealthiest countries, saw its sugar industry — long its economic backbone — collapse. Grand agricultural pledges failed. Chronic shortages became normal. Today, the island faces blackouts lasting up to 12 hours a day, triple-digit inflation, medicine scarcity, and one of the largest waves of emigration in its history.

“The promises,” Ferrer says, “turned into ration books.”

Ferrer’s own debut confrontation with the regime began when he joined the Varela Project led by democracy activist Oswaldo Payá, which sought a national referendum on democratic reforms. He was later eliminated by regime forces.

In March 2003, during the crackdown known as the Black Spring, state security agents swept through the country, arresting 75 dissidents. Ferrer understood that the noose of the Cuban regime was about to tighten around him, too.

“They searched my house for ten hours,” Ferrer recalls. “They took computers, papers, my children’s toys, food, medicine — everything. They wanted to erase us.”

He was held in Santiago’s Versailles detention center, isolated for 40 days in a mosquito-infested cell. Interrogations came without schedule. Sleep was systematically disrupted, and violent criminals were placed in his cell.

Charged under Cuba’s Law 88 — the so-called “Muzzle Law,” which prohibits any type of expression that the regime considers opposed to its interests or to its remaining in power, Ferrer says they did everything they could to destabilize him emotionally.

He faced what he calls “a performance, not a trial,” complete with false witnesses. The prosecution sought the death penalty, but the judge did him a favor and instead he received 25 years in a maximum-security prison known as Kilómetro Cinco y Medio.

On his first day in prison, Ferrer was paid a personal visit by the prison commander, who wanted to make a deal.

“He explained to me very nicely that it was not worthwhile for me to cause problems in prison, to desist from any kind of activity that would rile up the inmates. He also warned me not to reveal the various crimes that I would surely witness, and not to expose the abuses and the tortures that I alone was going to experience.”

From time to time, they would pull Ferrer out of his cell and put him into a punishment cell. Those cells were dark, stinking, and infested with worms. During one 46-day stretch, during the cold winter nights, they only allowed him to wear shorts and an undershirt, and allowed him only six showers (with freezing water) during that time.

After a year, Ferrer was transferred to Kilómetro Ocho in Camagüey — nicknamed Perdí la Llave.

“It means ‘I lost the key,’ ” he explains. “Because once you enter, you don’t come out.”

There, the punishment cells were pitch-black. “I couldn’t even see my own hands,” he remembers. “And the food was practically nonexistent — they confiscated the food my family had sent. During those periods, I couldn’t read, couldn’t write, couldn’t communicate with anyone.”

After eight years, amid sustained US and international pressure, Ferrer was released in 2011 under a conditional arrangement. The freedom proved fragile.

Revolving Door

When Fidel Castro died in 2016, power formally passed to his brother Raúl Castro, who had been effectively leading the country for almost a decade. By the time Raúl Castro was replaced by Miguel Díaz-Canel, the economy had deteriorated even further, and many citizens suddenly dared to find an alternative in Ferrer’s opposition party.

UNPACU expanded, distributing food and medicine in poor neighborhoods while documenting abuses. As economic conditions worsened, support grew — but so did arrests.

In 2019, Ferrer was accused of attempted murder following a traffic collision with a police vehicle, which he claims was a staged incident in order to neutralize him. When it came to the trial, though, there were enough real witnesses who gave testimony that contradicted the charges, and he was ultimately released after two brutal weeks in detention.

A year later, in 2020, he was convicted of kidnapping in what he says was a fabricated case and sentenced to four and a half years. In Aguadores prison, he says he suffered around-the-clock beatings after which the guards would make him lie on the floor. During the boiling-hot afternoons, they would take him to the yard and make him lie down in the scorching sun with no water for hours, where the temperatures reached up to 120 degrees [49°C].

The demonstrations that took place across Cuba by UNPACU activists and the intervention of the US Senate and the European Parliament led to Ferrer’s release after half a year, when he was confined to house arrest.

But then came the nationwide protests of July 2021 — the largest since 1959 — which triggered another arrest. Ferrer and his son were detained. His son was freed after a week.

After a month in the dank, infested detention center, Ferrer was sent to Mar Verde prison, where he was locked in an isolation cell and could barely breathe from the intense heat. There, he was beaten — his nose was broken and his teeth damaged, and he says he was given spoiled food specifically to make him sick. He began having severe headaches and even hallucinations.

Believing his food was deliberately contaminated, he stopped eating prison meals — a decision that weakened him dramatically, until his family succeeded in transferring in some basic food products.

But then it turned into something darker.

Guards allegedly disabled security cameras, and then, he says. “They plugged my nose, pressed my throat and forced me to open my mouth. They stuck a funnel into my throat and poured down rotten soup with the most unbearable smell. With a pure survival instinct, I forced my fingers into my mouth and vomited everything. But the guards didn’t like that, so they went around to collect a dozen of the most violent inmates, ordered them to collect the filth from the floor, and force it down me again.”

In that moment, he says, survival overtook defiance.

“I understood I would die there.”

But he didn’t. A little over three months ago, after a formal request from the US government, Ferrer was released from prison and allowed to depart for the US, together with his family members. For more than three years, US officials had called on the Cuban government to release Ferrer.

“Ferrer’s leadership and tireless advocacy for the Cuban people was a threat to the regime, which repeatedly imprisoned and tortured him,” said US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. “We are glad that Ferrer is now free from the regime’s oppression.”

Ferrer was originally released on parole in January 2025, just days after President Biden at the end of his term announced the removal of Cuba from a US list of countries that support terrorism; Cuban officials had agreed to a Vatican request to free Cubans jailed for anti-government activity.

The incoming Trump administration, however, reversed the Biden decision and re-listed Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism shortly after taking office.

And so, in April, Ferrer’s early release was revoked, and he was once again imprisoned, this time on allegations that he had violated his parole.

In the months since last summer, Rubio had called out the Cuban government for torturing Ferrer and demanded “immediate proof of life and the release of all political prisoners.”

Finally, under quiet international mediation, Ferrer was released once more. When threats extended to his wife and young child, he agreed to leave Cuba. At that point, Ferrer said he would accept exile rather than continue to be tortured in prison.

Today he lives in Miami as part of a vast Cuban exile community. But exile, he insists, is not surrender. He remains in contact with supporters inside Cuba — including, he claims, sympathizers within the military.

“I have much support among senior ranks in the regime,” he says. “Since I’m in the US, they’ve bravely turned to me — I’m in contact with several senior officers. They yearn for Cuba to become democratic, for the repression to end.”

Outside the island, the slogans are louder, but inside Cuba, it’s still just whispered conversations at best.

“We will need sacrifice,” Ferrer says. “But it will happen.”

For now, though, the street in Palmarito de Cauto grows dark again each evening. The Fidel Castro portrait still hangs and the flag still flutters in the warm breeze. But the silence, Ferrer believes, is no longer as certain as it once was.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1100)

Oops! We could not locate your form.