Right Side of the Law

| January 27, 2026Nearly a year after the six families had moved in, our intensive efforts notwithstanding, there was still no eiruv

Photos: AbstractZen

E

iruvin are all about boundaries. Physical boundaries demarcate the eiruv border. Halachic boundaries identify what constitutes a kosher eiruv. But interreligious boundaries that pit eiruvin against other religions? That was a new one for me….

The fledgling frum community of Crystal, Nevada consisted of a close-knit group of six families who had moved to the southwestern United States to strengthen Jewish awareness and observance. Rabbi Cohen and Rabbi Klein were designated as the roshei kollel, Rabbi Levi became the head of their tiny Torah day school, and another three yungeleit moved in as full-time members of the kollel. Once the mikveh and shul were in place, the Crystal Torah community was officially up and running… with one exception. The eiruv.

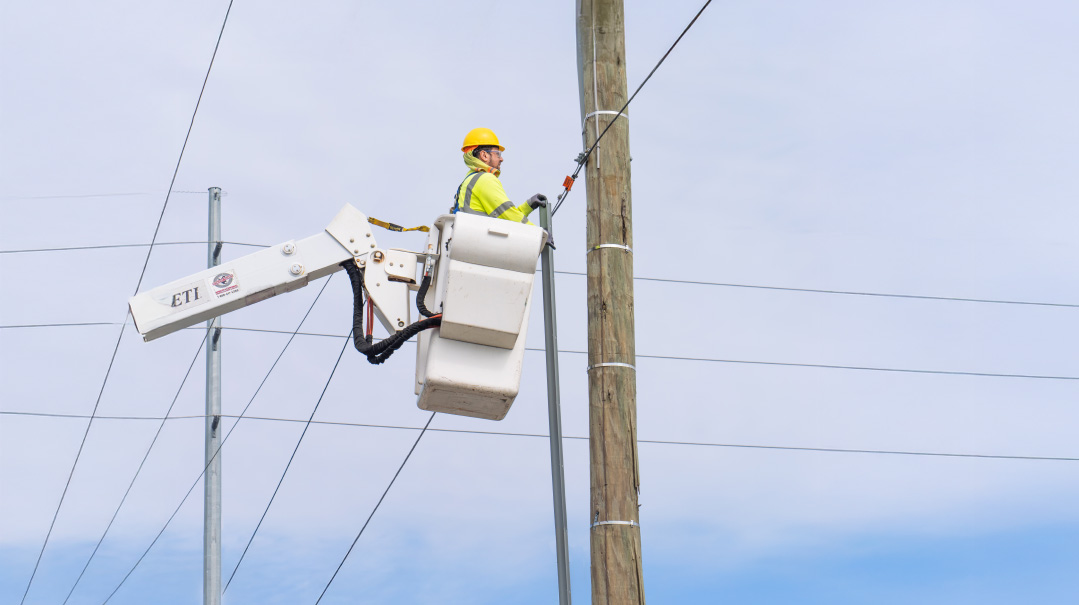

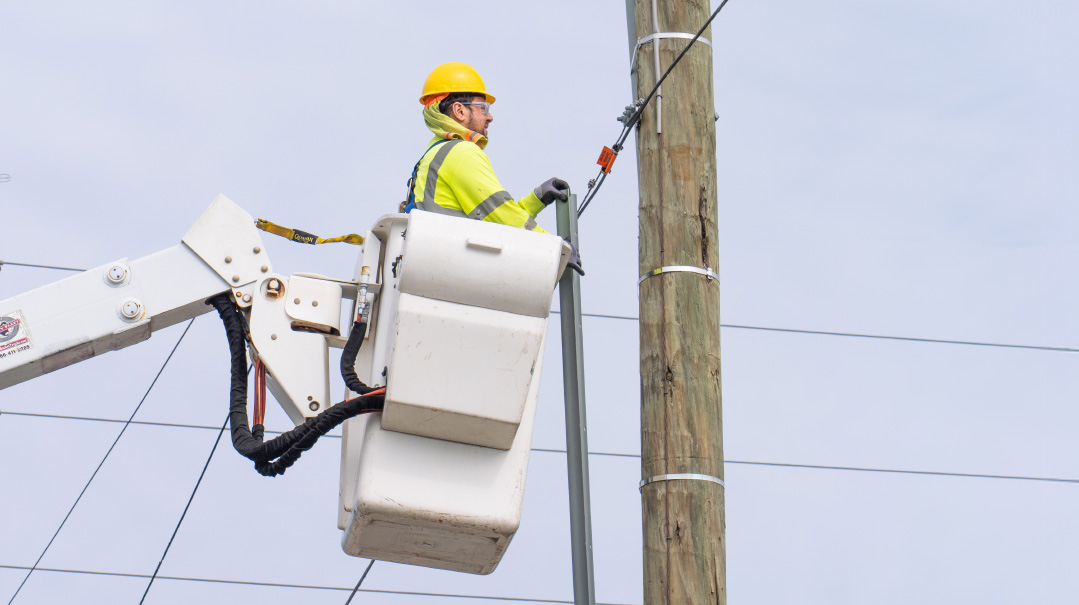

Three months before the first family moved in, I’d begun working with the rabbis on creating an eiruv to surround the city of Crystal. We had determined the area that should be included within the eiruv boundaries and found a donor who would underwrite the significant financial burden. But when we applied for permits from the city of Crystal’s utility company, we hit one barrier after the next. The hoops the utility company wanted us to jump could fill a book of (e.g., hiring a Navajo contracting company to oversee eiruv work, taking online certification courses in various safety procedures, and upward of 100 hours spent on useless paperwork).

Nearly a year after the six families had moved in, our intensive efforts notwithstanding, there was still no eiruv. The ladies and children were itching to be able to walk to shul on Shabbos morning and to visit each other on Shabbos afternoon. It was time for Eiruv Plan B.

All the kollel families had settled in a quiet development called Crystal Shores, just a short walk from the kollel/shul building. If the Crystal city eiruv would take another year or two or ten to erect, how about a small, relatively inexpensive eiruv around Crystal Shores? This temporary eiruv would provide some relief to the families while the larger eiruv battle ensued.

Rabbi Klein, a friendly and well-regarded board member of the Crystal Shores HOA, proposed the idea at the very next board meeting. “We’d like to establish a symbolic border around the community that will allow Orthodox Jews to carry within its confines on the Sabbath,” he explained to the group of gentiles. “This will benefit community members who would like to push baby carriages, carry water bottles, or push elderly relatives in wheelchairs.”

The HOA board members, being more accustomed to discussing hours of permitted sprinkler operation and quiet-time enforcement, were taken aback at this unusual request. “We’ll need to consult our lawyers to see if this request is viable,” intoned the president of the board, while all the other members nodded somberly.

The request was, apparently, not viable. Approximately four months later, the board issued a letter of denial, stating that allowing an eiruv constituted “religious favoritism.” There would be no Crystal Shores eiruv, for fear of promoting Orthodox Judaism over other religious sects.

In my opinion, the Crystal Shores decision was less about religious favoritism and more about religious discrimination. How would allowing Jews to carry on Shabbos overshadow the religious rights of Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists?

Rabbi Ezra Sarna, the OU’s director of Halacha and Torah Initiatives, agreed with me.

“Let me introduce you to a law firm that has assisted with several high-profile eiruv discrimination cases,” Rabbi Sarna suggested. “These gentlemen have a track record of proving the legality of eiruvin.”

Well, add Crystal Shores to the list of eiruvin who owe a debt of gratitude to the law firm Goldberg, Goldstein and Gold LLP. Mr. Gold issued a letter to the Crystal Shores attorneys suggesting that the same religious accommodation extended to Christians hanging holiday lights within Crystal Shores be extended to Jews who wish to carry on Shabbos. He also detailed a list of 90 cities in the United States that legally support an eiruv and reiterated the unobtrusive nature of an eiruv structure (certainly less noticeable than holiday lights!).

Suddenly, correspondence with Crystal Shore’s lawyers shifted from, “Sorry, no,” to “Let’s see some samples of eiruv materials so we can determine what looks right for our community.”

Within another four months, permission for the Crystal Shores eiruv was secured, and I rushed off to Crystal to begin building. Ten months from the initial Crystal Shores eiruv proposal and two days before Succos, the Crystal Shores eiruv was ready.

Most Jews living in frum communities hardly think about the eiruv. Its legality, presence, and kashrus are taken for granted. In some cases, though, the eiruv becomes a battle of outsized proportions, and then the community suddenly appreciates its presence in a whole new way. It may take months or years to get an eiruv up and running, but promoting shemiras Shabbos and oneg Shabbos is definitely a cause worth pushing the boundaries for.

*Names and locations, aside from the OU’s Rabbi Ezra Sarna, have been changed to protect the identity of those involved.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1097)

Oops! We could not locate your form.