Brain Trust

| January 13, 2026I went to sleep in March and woke up in August. As a walking miracle, why was I on the run?

IT

was Sunday night, a week after Purim in 2024. We weren’t quite up to the pre-Pesach marathon yet, so I went to sleep in preparation for another ordinary Monday morning.

“Ordinary,” though, was a rather relative term during these difficult months of the Gaza War. As a longtime limudei chol (English, history, science) teacher in the dati-leumi (National Religious) school system, many of my former students were risking their lives fighting the terrorists in Gaza, and at least one had already lost his life in the war zone. It was a shattering time for the Yidden of Eretz Yisrael. When we recited Unesaneh Tokef a few months previously during the Yamim Noraim of 5784, little did we dream just how prescient and tangible the words “mi yichyeh u’mi yamus” would be for many of us in the coming year.

And little did I know when I went to sleep that night that I, too, would be one of those whose gezeirah was sealed in Tishrei, that my life was about to be changed forever.

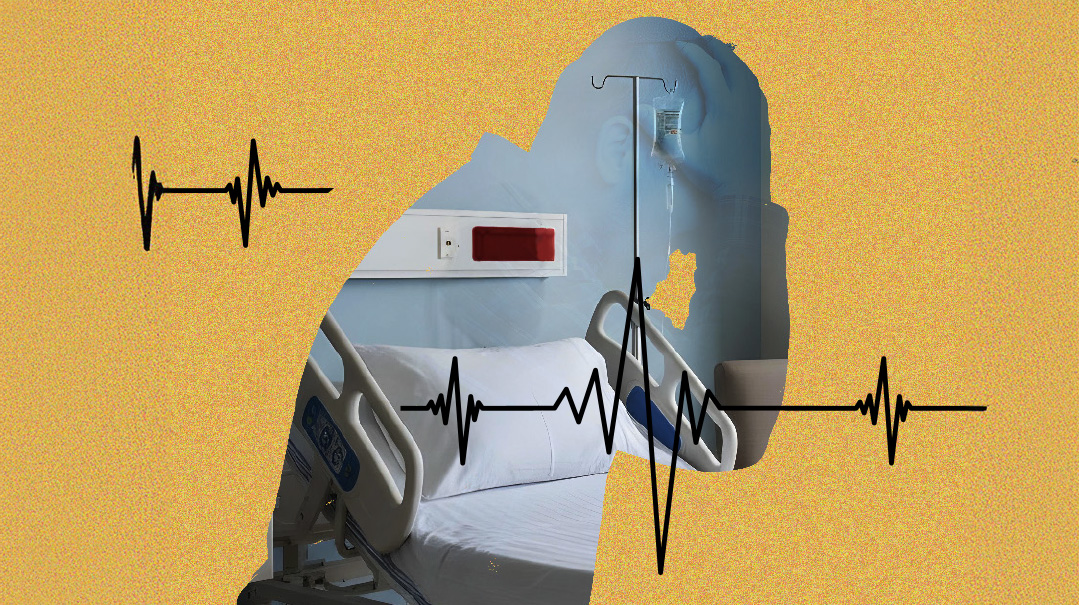

The first thing I remember upon waking up was finding myself in a spacious, multi-bed room and lying in what looked very much like a hospital bed, even though there didn’t appear to be any of the machinery generally associated with a hospital ward. As I shook myself out of my sleepy state, I noticed a number of things indicating that something was very wrong.

One, my body was loosely tied down to the mattress, and there were guardrails around the edges of the bed. Two, I realized that although my legs weren’t bandaged and I could bend my knees and wiggle my toes, I somehow knew I couldn’t walk. Three, I definitely felt like a chunk of time had passed since I had gone to bed that Sunday night on 22 Adar. I felt like I’d been asleep for maybe as long as a week.

I had vague memories swirling around my head of recent conversations with various people, but the last clear thing I remembered was of the Purim seudah that my family and I had enjoyed at a friend’s house a week before that night.

My wife was nearby, looking at me. Our conversation (and my thoughts) went something like this:

Me: Where am I?

My wife: You’re in Raanana, in a rehabilitation center called Beit Levenstein. (I later found out that this was considered the best rehabilitation center in Israel.)

Wait a minute — rehabilitation center?? Don’t people go there after being in a hospital? But when had I been in a hospital? I looked at my wife uncomprehendingly.

My wife: You had a brain hemorrhage.

Me: Wait, is that something like a stroke? And wait a minute —is it Pesach yet? (Last I remembered, it was around three weeks before Pesach.)

Me: Was it already Pesach?

My wife: Yes — a while ago.

Huh?? Passover had, uh, passed over?

Actually, I felt a little relieved about that piece of information. Making sure that the kitchen was cleaned of chametz always made me nervous. Well, it looked like I wouldn’t have that particular concern for another year.

But wait a minute — what day was it now? I had a vague memory of speaking to somebody about Tishah B’Av.

Me: Was it already Tishah B’Av?

My wife: Yes — around two weeks ago.

The realization suddenly dawned on me. I’d gone to sleep toward the end of Adar, and now it was at least the middle of Av. Nissan, Iyar, Sivan, Tammuz, at least half of Av. Plus eight days of Adar. That’s almost five months. I’d apparently slept from March to August.

Here’s a little personal background, which will help put my experience into perspective. I’m in my late fifties and have lived in Eretz Yisrael for over three decades. I was born in the late 1960s and grew up in an Orthodox community outside New York. (Like most frum “out-of-town” kehillos at the time, my neighbors were shomrei Torah u’mitzvos but not yeshivish. Baruch Hashem, Torah Umesorah was at the time opening up day schools throughout the country, and many parents were sending their children to receive a stronger Jewish education than what was available for the previous generation. And for us, that education paid off: One of my brothers became a prominent rosh kollel, and my sister eventually married a well-known figure of Agudath Israel in America.

Like many of my peers, I gradually took Torah learning more seriously and also slowly distanced myself from the non-Jewish culture in which we all grew up. Most importantly, I developed a strong desire to consult with daas Torah as much as possible. I was very lucky to form a close relationship with Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky, and spent around 30 years turning to him for guidance. (I stayed in contact with the Rosh Yeshivah after making aliyah, and today, I continue to turn to the rabbanim in our midst for guidance.)

After learning for a few years in post-high school yeshivos, I went to YU and earned a degree in science, and then moved to Eretz Yisrael to seek parnassah. I eventually chose to become a teacher and found my niche in education with the knitted-kippah world, although my students know that I base my hashkafos along the lines of the rabbanim of the mainstream chareidi world.

One of the first things my students asked me after I returned to the world of the living was about the difference between a stroke and a hemorrhage. I told them to picture the pipes that bring the water into your house. In a stroke, the pipe clogs up and blocks the water flow. In a hemorrhage, the pipe bursts open and sends the water rushing out everywhere except into the shower or kitchen sink.

Either way, though, no water enters the places that need it most. It means that not enough blood is getting to where the blood — and the oxygen it carries — is needed. And if the cells don’t receive enough oxygen, they can chalilah become damaged or die.

As I have no recollection of what happened from the night of 22 Adar until after Tishah B’Av, I will report what happened as described by my wife, my daughter, and the doctors’ reports that I later perused:

Sometime between one and two in the morning (April 1, 2024), my wife woke up to find me experiencing terrible pain in my head and insisting that she call an ambulance. The EMTs who arrived found me conscious and rushed me to Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Bayit V’Gan. Following an MRI which revealed bleeding in the brain, the doctors performed emergency surgery which lasted at least four hours.

One of my brothers in the States was receiving real-time updates during my operation, and when he heard that the surgery wasn’t going smoothly at first, he sat down to learn — for all I know, it was the zechus that tipped the scales.

Because so much time had elapsed with my brain not receiving enough oxygen, which meant that there was suspected brain damage, the doctors decided to keep me in an induced coma for an indefinite period of time to allow my brain to recuperate. I slept through Pesach, Sefiras Ha’omer, and Shavuos. (My students laughed when I told them it was the first time in my life that I followed their minhag not to say Tachanun on the 5th of Iyar, Yom Ha’atzmaut.)

Finally, the doctors allowed me to awaken, with no clue as to how well I would function, communicate, or recognize my family and friends. Sometime after Shavuos, I opened my eyes, and very, very gradually began to communicate with the people around me. Baruch Hashem, I recognized my wife and daughter and the others who visited me. I regained my ability to eat by mouth, and could be taken around the hospital in a wheelchair — even to the hospital’s Beit Knesset. In July, I was transferred to the rehabilitation center in Raanana to begin an extensive program of physiotherapy and occupational therapy. I would live at the center for the next four months.

However, even after moving to Raanana, my brain could not yet retain short-term memories. As such, I do not remember anything from my stay in Shaare Zedek, even after I’d woken up, and very little from my first few weeks in rehab — until that day in August when I became aware of where I was and what had happened to me.

But even then, I discovered that I was suffering from memory loss. I couldn’t remember what my home in Beit Shemesh looked like, or even if it consisted of one or two floors. I couldn’t remember the names of some of my longtime neighbors until my wife mentioned their names. I did remember where I taught, but couldn’t conjure up what the school building looked like, or remember the names of my students (luckily, I found I could remember the names of my relatives). I knew I had committed to memory parts of Pirkei Avos, but now I couldn’t recall a single mishnah. To top it all off, I found that I’d forgotten some of my Hebrew, even though I knew that I had been fluent after living here for so long.

There were other problems. The main one was that my body had forgotten how to walk, and it would take months to retrain my legs to obey my brain. In addition, my vision was impaired, and I couldn’t read the writing on a laptop screen even with my glasses. My sense of taste was affected, and eating was less enjoyable. Moreover, I had developed epilepsy, which explained the guardrails around my bed. They were to prevent my shaking body from rolling off while I slept. As for the ropes tying me down — well, I did have a vague memory of climbing over the guardrails one night to escape my “prison” and toppling to the floor, which forced the doctors to take measures to save me from harming myself.

Since I couldn’t get out of bed by myself, and since the nurses had many patients (who were worse off) to attend to, I had to wait every morning for my turn to be helped out of bed and into a shower. Then I had to be dressed and placed in my wheelchair so that I could wheel myself (not all patients could do that) to breakfast. I had no choice but to eat something light before davening, and then to daven without tefillin because I couldn’t put them on by myself — my hands were too uncoordinated to wrap the straps on my arm. Only in the afternoon would either a visitor or one of rabbanim on the site help me put on tefillin for Krias Shema. Starting in the morning, I would be taken to various floors or buildings (Beit Levenstein is a huge compound) for exercises to get my legs working, my coordination sharpened, and my memories restored. I also underwent therapy to help me deal with the emotional upheaval of my experience.

Meanwhile, my wife and daughter moved into the home of a wonderful local family that provided them with free lodgings for those four months (my daughter even found part-time employment), and they came every day, including Shabbos and Yom Tov, when we were able to eat together. (There was an area where families could enjoy private meals and keep their food warm on the hotplates.) My mother and siblings flew in to visit (my father couldn’t fly for medical reasons), and friends and Israeli relatives and even my students and their parents came fairly often (though my students all had to remind me of their names).

I also was able to do some things for my neshamah. In the evenings and on Shabbos mornings, I would be taken down to the shul, where I could daven Minchah/Maariv with a minyan as well as attend a shiur by a wonderful rav who was a source of constant encouragement to us patients. A local resident came in to learn a little Gemara with me, although it would be months before I could properly focus on any sugya, and most of my daily learning was Chumash with Rashi. The Yamim Noraim came, and for the first time in my life, I became a Yamim Noraim chazzan — for about three minutes. The official Yom Kippur davening was Sephardi nusach of Eidot Hamizrach, and I complained to the gabbai that I really didn’t want to skip Unesaneh Tokef (which isn’t in their machzor). To his great credit, the gabbai stopped the chazzan in the middle of Mussaf and had me lead the tzibbur just for that tefillah.

Come Succos, there was a good-sized succah on the premises for meals (although there was no way I could arrange to sleep in it), and a good friend procured a beautiful set of arba minim.

Throughout my stay (and the entire year), family, friends, my students and their parents and many others were saying Tehillim for my recovery. That means I owe far more than I realize — not only to the wonderful medical shlichim at Shaare Zedek and Beit Levenstein, but also to the hundreds who were davening for me.

My neurologist later informed me that this type of brain bleed often causes irreversible damage, Rachmana litzlan, and my recovery was nothing short of a miracle. Back in Beit Shemesh, a neighbor even started a worldwide Tehillim chat, and in the States, my sister-in-law began a nightly (and later weekly) conference call that would have everybody contribute to completing all of Sefer Tehillim each time. I’m told that between everybody’s efforts, Sefer Tehillim was completed over 200 times in the months following my hospitalization.

By Cheshvan/November 2024, I had recovered enough to be released and sent back home to Beit Shemesh, but I still had a very long road ahead. I still could not walk more than a few steps, and I required a live-in foreign aide to shower and dress me, and take me out for daily walks while I slowly increased my distance capacity. This went on for ten weeks until the end of January 2025, when I could finally get around by myself and was able to let my caretaker go. (He was a good Indian man, and I was very happy to hear that he soon found another family to work for.) Around this time, my neighbors threw for me a wonderful seudas hoda’ah, which coincided with another visit from my mother.

After that, I continued to improve. It took me a month to relearn how to balance myself while biking (as biking had always been my primary way to travel to and from shul or work).

Meanwhile, I had to return to Shaare Zedek a few times for follow-up tests to make sure that I wasn’t in danger of another mishap, chas v’shalom. Baruch Hashem, those tests showed nothing wrong. I also underwent a lot of testing at various eye clinics to help me regain my pre-hemorrhage vision, which thankfully I did. What was very unpleasant, however, was my body’s withdrawal symptoms when the doctors weaned me off the various medications I no longer needed (such as for the epilepsy). For two months, I suffered from severe insomnia and found that I couldn’t sleep for more than two hours a night.

Finally, by Pesach 2025, just over a year later, I had baruch Hashem regained both my physical capabilities and my memory (and I was sleeping again), and I was ready to return to my teaching. Although my finances were now adequately covered by Bituach Leumi (Israel’s social security), and my school even paid me sick leave for longer than they were required to, I badly wanted to return to the job that I loved. Also, I had always shteiged in Torah better when I spent a good part of my day working.

I started with tutoring small groups of students and then gradually increased both the number of students and the hours in the classroom, until I was once again doing the same number of hours as before.

My saga, however, wasn’t yet over, because I still had the greatest hurdle to overcome. Yes, Hashem had returned to me my physical and mental health — but my emotional health was another chapter.

It was Sivan/June 2025, and I still felt pretty much the same as when I’d woken up almost a year before: I couldn’t shake the feeling that Hashem was out to get me, and it was just a matter of time until He did.

I’d always prided myself on having a relatively strong sense of emunah and even enjoyed speaking one-on-one with Hashem. From the time that I “woke up” in Raanana, though, I discovered that this was no longer the case. Of course, I never doubted that it was Hashem Who had made me sick in the first place — but this, in fact, was the problem.

I couldn’t get over the fact that one moment I had been a healthy, energetic teacher serving Hashem in many ways — and the next moment Hashem had basically pulled the rug out from under me and left me (at least at the beginning) a shell of my former self. My health, my learning, my career, my future, even some of my memories — all gone in the blink of an eye, with practically no advance warning.

It didn’t make me feel better that I was gradually improving. First of all, my recovery was progressing very slowly, and I was never sure that I would ever regain my former capabilities. However, even when I got back to doing almost everything I used to do, I couldn’t shake the fear that had haunted me for almost a year: If Hashem could do this to me once, what’s to stop Him from doing it again?

The doctors, for their part, never discovered what had caused the hemorrhage in the first place. Before that fateful night, I had been a relatively healthy individual with normal blood pressure and no particularly unhealthy habits — and Hashem made the blood vessel in my head rupture in my sleep, just like that. Sure, I’d done my hishtadlus and underwent the requisite MRIs and blood pressure monitoring to ensure that I was out of danger for now, but since when is Hashem ever bound by doctors’ reassurances?

It’s easy to mouth off platitudes about emunah and bitachon, but now I found that I just couldn’t internalize any of those concepts. I was panicky and frightened over what Hashem could do to me, and this fear was preventing me from experiencing any simchas chayim whatsoever. Even the knowledge that Hashem had allowed me to fully recover didn’t make me feel better — there was no guarantee that He would allow me to continue to enjoy good health.

What could I do? I was slated to return to full-time teaching in Elul, so I got busy over the summer with talking out my fears as much as possible. Rabbanim, close friends, colleagues, a therapist, and even my older students — I had a steady stream of DMCs with all of them. I traveled back to the US to celebrate a gala seudas hoda’ah with my parents and all of the family who couldn’t join my celebration in Israel, and I made sure to speak with relatives about what I was going through. “De’agah b’lev ish yashchenah” (Mishlei 12:25) — speak out your worries with others.” Meanwhile, I learned Torah, I davened, and I waited for a breakthrough of some sort.

And then it happened.

It was the beginning of Elul, and I was back to teaching in Beit Shemesh. I can’t pinpoint which day this happened, nor can I describe any specific event that brought on this experience. All I can say is that one day, I found myself picturing HaKadosh Baruch Hu Himself booming out to me with perhaps the same type of voice that He used when He spoke to Iyov from the storm wind. And these are the words that I could picture Him saying:

Dovid, it is very true that I can do anything with My creations. As you have just experienced, I can do whatever I wish, and I can make it happen whenever, wherever, and however I wish. There is no guarantee whatsoever that any person will continue to enjoy life, health, family, career, or finances. If I so decree, then it will happen. And until Mashiach arrives, no human will ever be able to truly understand these decrees.

But with all of that, you must get it through your head: I am not out to get you. For reasons you cannot know, I endangered your life and took away your health, and now I have currently returned your life and your health and even your job. Now, use My gifts to serve Me with joy. Even within My decrees that seem difficult or unpleasant, I will always be there to help My children deal with them. And no matter what is happening, ivdu es hashem b’simchah. Stop worrying and start enjoying the life that I give you, that I breathe into every minute, and invite others to enjoy that life together with you.

I found this perspective considerably amplified when I later asked my neurologist about the extent of the brain damage that I had initially experienced. He told me that when the blood touches the brain, it can cause irreversible damage, as well as the threat of damage from swelling, inflammation, seizures and strokes. The odds are against a person making a full recovery.

“So as far as you assume, the blood didn’t actually touch my brain?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “It touched the brain, quite a lot. And despite the very large bleed that should have caused at least some amount of irreversible damage, you somehow managed to avoid that and had a complete recovery. Hodu LaHashem ki tov.”

So Hashem made a gezeirah, and also a true miracle for me. And with that realization, I found myself going from a drought to a deluge. Suddenly, I was shteiging, teaching, and just doing things better than I ever had done before. I entered the Yamim Noraim a driven man, determined to accomplish things that I had procrastinated on for decades — after all, I had a new lease on life, a gift that wasn’t to be squandered. I started the new school year with greater fire and enthusiasm than I’d ever felt in more than two decades of teaching. I contacted friends and acquaintances with whom I had lost contact for years and caught up with them, and I started emailing relatives far more frequently (and driving some of them nuts, but that’s part of my newfound simchas chayim).

I’ve even added on two new chavrusas to my daily schedule, even though I’m teaching more hours than ever. I’m continuing to relearn Pirkei Avos by heart, and now I’ve committed myself to memorizing Perek Shirah as well. I’ve also become more involved with reaching out to my neighbors and students to help give them chizuk with whatever issues they may be dealing with. I’m doing my best to make use of my medical odyssey to give my family, students, and community more enthusiasm for life and for avodas Hashem — my small contribution to help others appreciate each and every gift that the Ribbono Shel Olam provides us with every second of our lives. And for that opportunity, thank You, Hashem!

The writer (using a pseudonym) is a longtime educator in Beit Shemesh.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1095)

Oops! We could not locate your form.