Shalom, Somaliland

| January 6, 2026Who would think Israel would be the center of their celebration?

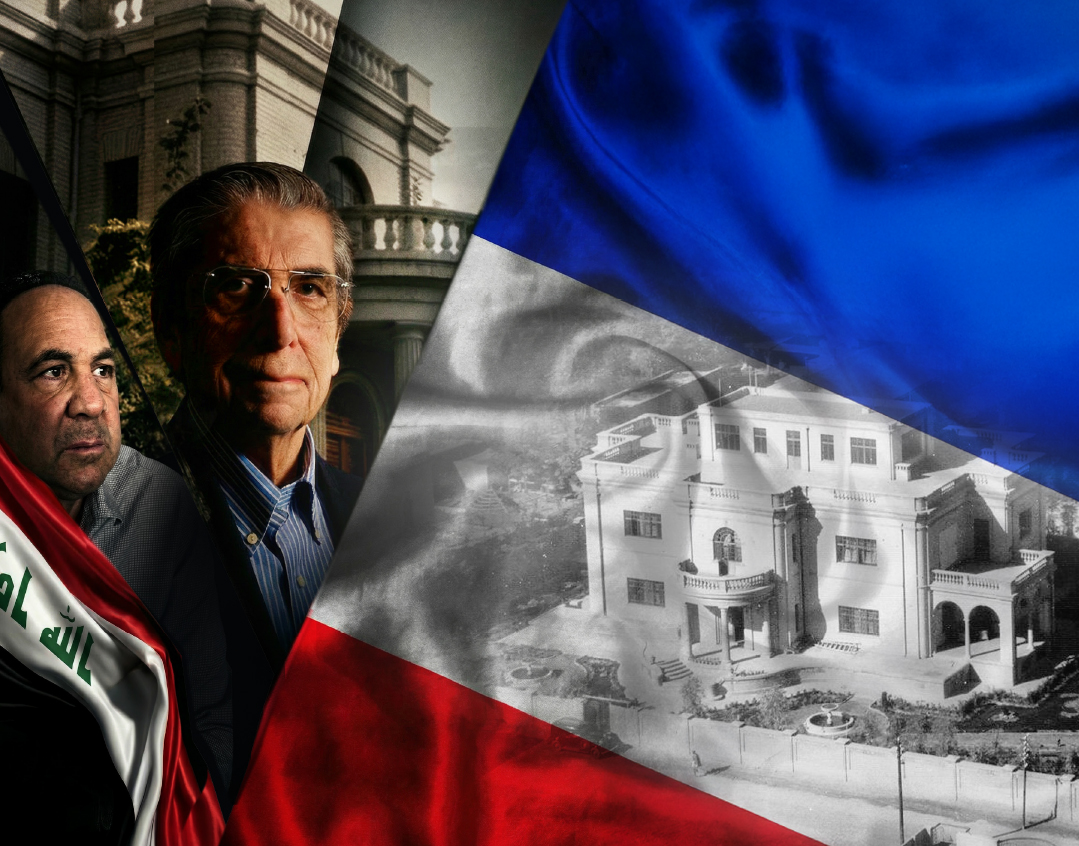

Photos: Eli Cobin

As soon as Israel declared its recognition of Somaliland, we were on the first flight out to this country that had been politically isolated for the last three decades. We thought we were going in order to witness a political transformation, but we had no idea that the spotlight would be on us — that with our yarmulkes and tzitzis, we’d be the focus of unbridled joy and celebration

T

he wild, spontaneous reception was totally unexpected.

We’d been in Somaliland less than 24 hours when we were guided by a police escort to a rally that took our breath away. Had we known what awaited us, we might have asked to return to the hotel, take a shower, and maybe I would have even changed out of my T-shirt to something a bit more dignified — but the whirlwind of spontaneous authenticity made everything happen in a racing blur of excitement and anticipation.

And so just three days after Israel officially recognized this country, our four-man group — the very first Israelis to set foot here — was led into the “stadium” of the capital city of Hargeisa.

Okay, so it’s not exactly a stadium by our standards — it’s really just a wide, open lot, almost like a giant sandbox. Here, in this third-world country on the northeastern corner of the Horn of Africa and most importantly, abutting the Gulf of Aden, a stadium requires only a huge flat area, more or less free of grass or shrubs, surrounded by thick stone walls. And that’s considered just fine by local standards.

From there, sensory overload struck us unexpectedly. Thousands of people — men, women, children of all ages — waved Israeli and Somaliland flags wildly, overcome with excitement at the Israelis who had finally come into their isolated space in a gesture of friendship, after three decades of not being recognized by any country that counts. And we weren’t even official diplomats, just a few Jews on a tour of the latest country to be recognized by Israel. The field was literally rocking, with flags, streamers, horns, music, and drums accompanying the chaotic noise of cheers and whoops, as we were royally escorted to the stage.

There, members of parliament, local officials, the city governor, the vice president — everyone who was anyone — awaited us. The presidential logo and portraits of the two most popular leaders, Benjamin Netanyahu and Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (commonly known as “Irro”), were displayed side by side, each one with an enormous smile. Clearly, both had reason to celebrate.

More than a Gesture

To understand the intensity of the frenzy, you need to grasp the political chessboard we were entering. Somaliland is not “just another African country”; it is arguably the most fascinating, if isolated, political startup of the past 30 years.

On paper, Somaliland is a “region in northern Somalia.” In reality, it’s a fully functioning state: stable democracy, parliament, currency (low but balanced), and a trained army of 70,000 soldiers. Their tragedy lies in the African Union’s “sacred borders” principle — the fear that recognition of one secession could unravel the entire continent, given the dozens of ongoing or frozen territorial disputes across Africa. Some disputes concern entire regions, while others focus on specific maritime or land boundaries. For three decades, Somaliland existed as a ghost state: physically present but invisible at the UN.

This is where Israel enters the story, and with timing nothing short of dramatic. Geographically, Somaliland sits on one of the world’s most strategic assets: the Horn of Africa, along the Gulf of Aden. The country is located opposite Yemen, at the maritime junction of the Gulf of Aden, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Red Sea — the chokepoint of global shipping and precisely the area where Yemen’s Houthi movement has been targeting international shipping lanes over the past two years.

Since Houthi attacks on shipping intensified following Hamas’s October 7 assault on Israel and the war that followed, many shipping companies have rerouted vessels around the Cape of Good Hope at a steep financial cost felt in part by Israeli consumers.

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland is far more than a diplomatic gesture. It links an unrecognized democracy in the Horn of Africa with Yemen’s internal power struggles, Saudi-Emirati rivalry over regional influence, and the Houthi threat to global trade. For Somaliland, it marks a historic breakthrough; for Israel, it’s a calculated gamble in a volatile arena — one that will not only create intelligence potential for Israel in monitoring Houthi activity, but will expand its strategic reach in the entire region.

Somaliland’s claim to independence rests on both a historical and legal foundation. The region was once a British colony known as British Somaliland, which gained independence in 1960. Just days later, it voluntarily united with the former Italian colony to form the Republic of Somalia.

That union, however, did not endure. Following the collapse of Somalia’s central government and the outbreak of civil war in the early 1990s, Somaliland declared that it was dissolving the union and reclaiming its independence.

Since its 1991 declaration, Somaliland has consistently argued that it did not secede from an existing state but rather restored its prior sovereignty within recognized borders. Somalia, the African Union, and most African states reject this claim, fearing that recognizing Somaliland could trigger a wave of secessionist movements across the continent. Despite its isolation, Somaliland has maintained a relatively stable government with minimal violence, especially compared to Somalia, making it a notable exception in a turbulent region. Over the past three decades, Somaliland has held presidential and parliamentary elections, including peaceful transfers of power, an unusual phenomenon in the region.

While lacking official international recognition, Somaliland has for years maintained an informal web of international relationships, including with Ethiopia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. It hosts foreign delegations and maintains diplomatic missions, but without embassies or full legal recognition. Various powers, including the US, Ethiopia, UAE, and several European countries, have long maintained military bases in the area, and it’s rumored that Israeli aircraft have landed there for refueling on stealth missions.

Official Israeli recognition was the game-changer they had waited for. While the US and Western nations have hesitated — wary of angering Somalia’s official government and other African-allied countries including Turkey — Netanyahu cut through the diplomatic norms, a move unprecedented in its boldness.

Yet there was a huge elephant in the room: Somaliland is a full Muslim country. In recent years, like much of the Muslim world, the population has been fed a hardline Gaza-centric narrative of genocide and dying children. The collision of Israeli recognition with Muslim solidarity with Gaza created a tension palpable when we Israelis arrived just two days after recognition. For the Somalilanders, Israel is a political savior ending economic isolation, but they still need to reconcile this with the narratives of a hostile Arab media. That’s one reason the incredible, exuberant welcome was so shocking.

Next week or next month, there might be planeloads of tourists, but it won’t be the same. We were the first, and the locals literally looked to us as their saviors. I’ve been to a lot of places around the globe, but I can honestly say that I’ve never experienced such a reception. Had I known, I would have definitely brought a suit.

Blocked Borders

As soon as word was out about Netanyahu’s dramatic phone call on Friday afternoon, the race to Somaliland was on. It began when a close friend and world traveler called and asked me to join him together with Rabbi Yosef Garmon, a former chief rabbi of Guatemala who has connections around the world and is active in delivering humanitarian aid and medicine across Africa and Latin America. My friend told me they were planning on leaving at the beginning of the week.

“I want to be there while the transformation happens,” he told me. There’s nothing like feeling the local energy while the iron is hot, he said. For him, it was one more square on his global checklist — he’s already traveled to over 150 countries. Was I in? Well, if I could hitch a ride for a unique experience, why miss it? I called another good friend, Israeli businessman Shlomi Peles, and the four of us set out.

We quickly booked flights to Dubai, hastily packed, and of course I prepared my special glasses that allow me to record secretly without locals knowing they are being filmed — a necessity in remote, third-world regions where bulky camera equipment frightens the locals. This way, we’d be able to document the experience authentically across dozens of situations.

But planning is one thing, reality another. The first leg seemed simple: flights to Dubai, then a short connection to Hargeisa. Or so we thought.

At Terminal 3 in Israel, it became clear the airline staff were not updated on Israel’s recognition. Diplomatic channels were not yet arranged to circumvent Somali sovereignty, which meant that to reach Somaliland, one would need a visa from Somalia — which does not allow entry from Israel. And we only discovered this at check-in.

We tried pulling our various protektziya connections, but in the end, nothing worked. The flight to Dubai took off without us, and there we were, stuck in a dead end at Ben-Gurion, our trip not even started.

Refusing to give up, we recalculated and launched plan B: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. From there, we would find our way. Ethiopia, a massive African country bordering Somalia and Somaliland, meant another visa and a nearly 700-kilometer drive along rough roads to the border, but we would deal with that later. At Ethiopian Airlines, this time we maintained ambiguity: no mention of Somaliland or politics, just “a flight to Addis Ababa, thank you.” We passed.

Early Tuesday morning, we landed in Ethiopia and decided to try our luck; instead of driving for hours, we’d take a domestic flight from Addis to Jijiga, a town near the Somaliland border.

While still in the Addis airport, we had the good fortune to meet a reporter from Israel’s Channel 14, who was on his way back from Paris. Yosef Garmon recognized him and convinced him to join our little group. Why not? If we all managed to get to Somaliland, it would be a scoop for him, too.

Let’s just say the Ethiopian city of Jijiga is hardly a vacation destination. The region is predominantly Somali Muslims, despite being under Ethiopian sovereignty. The city is conservative, extremely Muslim in character, and with Israeli recognition of Somaliland coming on the heels of the “Gaza genocide,” Israelis represented absolute evil in their eyes. Not a picnic

Here we first experienced the stark dissonance: The Ethiopian government is a strategic ally of Somaliland, needing a port outlet at Berbera, while the local Somali population, fed by Al-Jazeera narratives, views it through a hostile lens.

Walking through Jijiga felt like stepping centuries back. Through my glasses, I documented poverty unseen in the West: leaky shacks, dirt floors, barefoot children running in dust clouds, and no modern sanitary facilities. Had I pulled out a camera, our journey would have ended quickly and unpleasantly. The special glasses allowed me to capture the scenes without the natives being the wiser.

We hired a local driver for the two-hour drive to the border. But the driver, realizing that we were Israeli, launched into a string of curses in Arabic and broken English against Netanyahu and Israel. Still, he kept driving, and we just nodded along, hoping to survive until the border.

The road was a string of improvised checkpoints, each a test of our nerves, and the border itself was chaos: hundreds of vendors, armed soldiers, police, and opportunists looking for easy pickpocket targets. Following some sage advice we were given, we hid all Jewish markers — our yarmulkes and tzitzit were deep in our pockets — and paid the right hands to speed up our passage to the other side.

Flags and Cheers

And then, the transformation occurred.

Crossing into Somaliland, hostility and suspicion flipped to smiles and even hugs. Border police and officials welcomed us warmly, even pulling out a little Israeli flag and waving it. It turns out that Garmon, with his plethora of connections, was in contact with the royal staff, and they were waiting for us.

Minutes later, at the local immigration office, as we were met by cheers and a massive Israeli flag, out came our yarmulkes and tzitzis.

And that was just the beginning. Outside awaited brand-new Land Cruiser SUVs sent by the government, to take us to our hotel in Hargeisa. They handed us water and even took us to buy a SIM card. We noticed an expertly hidden gun beneath the steering wheel, making it clear that the Somaliland authorities took the Israelis seriously. Just meters separated our prior fear from this royal treatment.

Before we knew it, it was as if the entire nation came to greet us with Israeli flags and cheers. Why did these throngs dance with such abandon for strangers from Israel? I think it was mostly shock on their part. For 30 years, Somalilanders lived in their own isolated struggle, and recognition felt like their personal Exodus. So when we showed up to say hello — the first non-Africans these people had ever seen, that was enough to ignite their joy.

Wednesday morning was calmer, at least compared to yesterday’s upheaval. True, there’s no Chabad House yet for Jewish tourists where we could daven, but we did discover that there had once been an active Jewish community in these parts.

There are no known Jews living in Somaliland now, but the territory, sitting at the crossroad of commerce linking Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the wider Middle East, once contained small communities of Jewish merchants from across the Red Sea. Several hundred Jews from Yemen moved to Somaliland at the end of the 1800s, after the Ottoman Empire consolidated control over Yemen and allowed Yemeni citizens to migrate more freely. There were even a few synagogues, but they were destroyed when Italian Fascists took over the country in the 1930s. And once the State of Israel was declared in 1948, whatever was left of these small communities disbanded and moved. Today, though, there’s a certain tribal clan that claims to be descended from Jewish ancestors.

The day’s main destination was Hargeisa’s central market, but as soon as we set out, our driver got nervous. “I think you guys need security,” he told us. Initially we dismissed it — after all, people danced around us yesterday — but as soon as we stepped out and crowds gathered, we understood what he meant. In Somaliland, even admiration can become a crushing mob.

And so we were escorted by police to the market, with full protocol: officers assigned to us, a protective convoy ensuring safe passage through the bustling, chaotic bazaar. We walked through the market, a group of Israelis with armed escorts — just lacking paparazzi.

Again, my recording glasses captured it all, from women emerging from piles of meat to machines grinding spices in clouds of dust.

And then, after several hours in the colorful bazaar, we were led straight to Hargeisa’s stadium. True, it might not have been more than a large field, but for the thousands of locals waiting there, it was the center of the universe. Upon exiting the vehicles, security cleared the crowd for us. Passing through the screaming throngs, surrounded by local media and social networks, we were led to the stage.

Under giant banners of Bibi and Irro, someone pushed a microphone into my face and I managed to say in the local language, “Israel loves Somaliland,” which was enough to ignite the crowd. People sang “Am Yisrael Chai,” parliament members and local dignitaries lined up to take photos, and endless dance circles formed. Three hours of sensory overload under the blazing Somali sun. The locals’ joy, despite material poverty, was transcendent.

Before returning to the hotel, we stopped at a bank to exchange some money. The manager led us into his office as if we were senior foreign investors. Only then did I grasp the country’s true financial state: The local currency, the Somali shilling, is nearly worthless. With an exchange rate of one dollar to 10,000 Somali shillings, $100 yielded a mountain of bills and bags full of shillings. Even beggars carry phone numbers for digital transfers because cash is impractical.

Face of Freedom

Thursday morning, we visited the camel and livestock market. Primitive, chaotic, and fiercely competitive, it is the region’s primary food market. Camels sell for around $500, sufficient to feed a family for months. Security still remained essential, particularly after warnings from the Israeli Foreign Ministry, which was aware of our mission.

Finally, we departed via the Somaliland airport — which was surprisingly modern, servicing African Express Airways, Ethiopian Airlines, and some smaller companies. We boarded Ethiopian Airlines to Addis Ababa, but this time, we’d already accomplished our mission.

On the return flight, I reflected on the past 48 hours. The intensity, the joy — I’d never expected it, but now I understood it. For the past three decades, these people lived in an international prison — an invisible state. Suddenly, Israel arrived, and to them, it was a literal salvation. We were not just tourists or journalists. We were the face of their freedom.

Despite poverty and chaos, Somaliland has a priceless asset: location. Its proximity to Yemen and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait make it Israel’s hottest strategic asset in the Horn of Africa. Somaliland may seem like the third world, but for Israel, it’s the starting point of a new African frontier. Hopefully, we’ll merit to have many more such trips.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1094)

Oops! We could not locate your form.